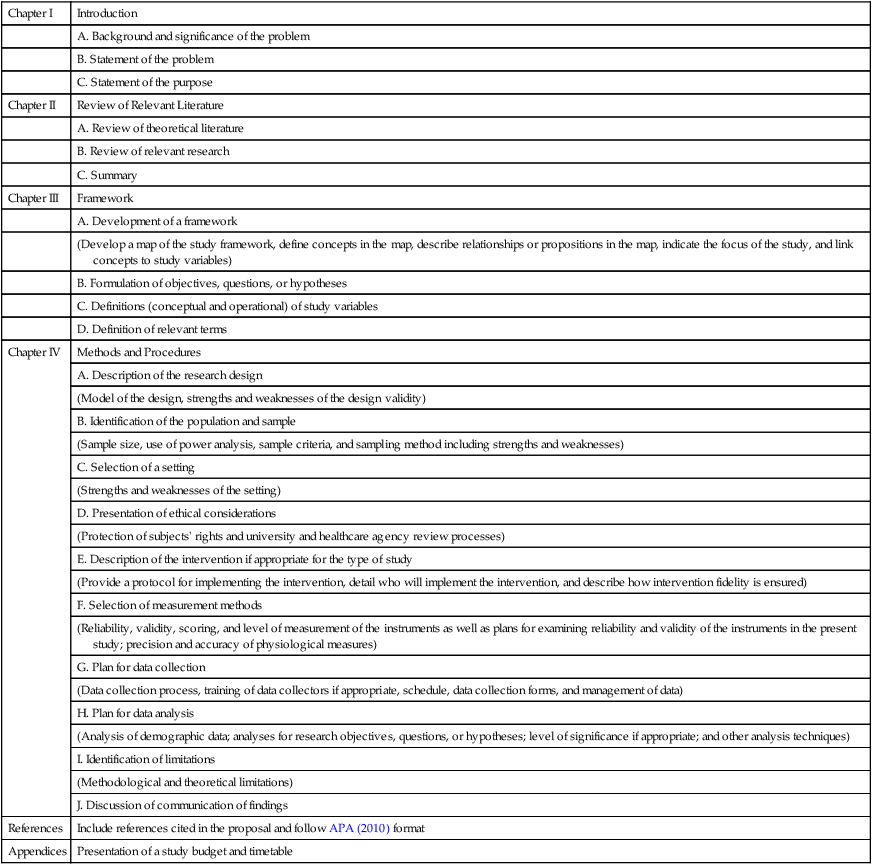

With a background in the quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, and intervention research methodologies, you are ready to propose a study. A research proposal is a written plan that identifies the major elements of a study, such as the research problem, purpose, and framework, and outlines the methods and procedures to conduct the proposed study. A proposal is a formal way to communicate ideas about a study to seek approval to conduct the study and obtain funding. Researchers who are seeking approval to conduct a study submit the proposal to a select group for review and, in many situations, verbally defend the proposal. Receiving approval to conduct research has become more complicated because of the increasing complexity of nursing studies, the difficulty involved in recruiting study participants, and increasing concerns over legal and ethical issues. In many large hospitals and healthcare corporations, both the lawyer and the institutional review board (IRB) evaluate the research proposals. The expanded number of healthcare studies being conducted has led to conflict among investigators over who has the right to recruit potential research participants. The increased number of proposed studies has resulted in greater difficulty in obtaining funding. Researchers need to develop a quality study proposal to facilitate university and clinical agency IRB approval, obtain funding, and conduct the study successfully. This chapter focuses on writing a research proposal and seeking approval to conduct a study. Chapter 29 presents the process of seeking funding for research. A well-written proposal communicates a significant, carefully planned research project; shows the qualifications of the researchers; and generates support for the project. Conducting research requires precision and rigorous attention to detail. Reviewers often judge a researcher’s ability to conduct a study by the quality of the proposal. A quality study proposal is clear, concise, and complete. Writing a quality proposal involves (1) developing ideas logically, (2) determining the depth or detail of the content of the proposal, (3) identifying critical points in the proposal, and (4) developing an esthetically appealing copy (Martin & Fleming, 2010; Merrill, 2011; Offredy & Vickers, 2010). The ideas in a research proposal must logically build on each other to justify or defend a study, just as a lawyer would logically organize information in the defense of a client. The researcher builds a case to justify why a problem should be studied and proposes the appropriate methodology for conducting the study. Each step in the research proposal builds on the problem statement to give a clear picture of the study and its merit (Merrill, 2011). Universities, medical centers, federal funding agencies, and grant writing consultants have developed websites to help researchers write successful proposals for quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, and intervention research. For example, the University of Michigan provides an online guide for proposal development (http://www.drda.umich.edu/proposals/PWG/pwgcomplete.html). The National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR, 2012) provides online training for developing nurse scientists at http://www.ninr.nih.gov/Training/OnlineDevelopingNurseScientists/. You can use a search engine of your choice, such as Google, and search for research proposal development training; proposal writing tips; courses on proposal development; and proposal guidelines for different universities, medical centers, and government agencies. In addition, various publications have been developed to help individuals improve their scientific writing skills (American Psychological Association [APA], 2010; Offredy & Vickers, 2010; Turabian, Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2007; University of Chicago Press Staff, 2010). The depth or detail of the content of a proposal is determined by guidelines developed by colleges or schools of nursing, funding agencies, and institutions where research is conducted. Guidelines provide specific directions for the development of a proposal and should be followed explicitly. Omission or misinterpretation of a guideline is frequently the basis for rejection or requiring revision. In addition to following the guidelines, you need to determine the amount of information necessary to describe each step of your study clearly. Often the reviewers of your proposal have varied expertise in the area of your study. The content in a proposal needs to be detailed enough to inform different types of readers yet concise enough to be interesting and easily reviewed (Martin & Fleming, 2010). The guidelines often stipulate a page limit, which determines the depth of the proposal. The relevant content of a research proposal is discussed later in this chapter and varies based on the purpose of the proposal. The key or critical points in a proposal must be evident, even to a hasty reader. You might highlight your critical points with bold or italicized type. Sometimes researchers create headings to emphasize critical content, or they may organize the content into tables or graphs. It is critical in a proposal to detail the background and significance of the research problem and purpose, study methodology, and research production plans (data collection and analysis plan, personnel, schedule, and budget) (APA, 2010; Offredy & Vickers, 2010; Turabian et al., 2007). An esthetically appealing copy is typed without spelling, punctuation, or grammatical errors. A proposal with excellent content that is poorly typed or formatted is not likely to receive the full attention or respect of the reviewers. The format used in typing the proposal should follow the guidelines developed by the reviewers or organization. If no particular format is requested, researchers commonly follow APA (2010) format. An appealing copy is legible (the print is dark enough to be read) with appropriate tables and figures to communicate essential information. You need to submit the proposal by the means requested as a mailed hard copy, an email attachment, or uploaded file. Student researchers develop proposals to communicate their research projects to the faculty and members of university and agency IRBs (see Chapter 9 for details on IRB membership and the approval process). Student proposals are written to satisfy requirements for a degree and are usually developed according to guidelines outlined by the faculty. The faculty member who will be assisting with the research project (the chair of the student’s thesis or dissertation committee) generally reviews these guidelines with the student. Each faculty member has a unique way of interpreting and emphasizing aspects of the guidelines. In addition, a student needs to evaluate the faculty member’s background regarding a research topic of interest and determine whether a productive working relationship can be developed. Faculty members who are actively involved in their own research have extensive knowledge and expertise that can be helpful to a novice researcher. Both the student and the faculty member benefit when a student becomes involved in an aspect of the faculty member’s research. This collaborative relationship can lead to the development of essential knowledge for providing evidenced-based nursing practice (Brown, 2009; Craig & Smyth, 2012; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). The content of a student proposal usually requires greater detail than a proposal developed for an agency or funding organization. The proposal is often the first three or four chapters of the student’s thesis or dissertation, and the proposed study is discussed in the future tense—that is, what the student will do in conducting the research. A student research proposal usually includes a title page with the title of the proposal, the name and credentials of the investigator, university name, and the date. You need to devote time to developing the title so that it accurately reflects the scope and content of the proposed study (Martin & Fleming, 2010). A quantitative research proposal usually includes a table of contents that reflects the following chapters or sections: (1) introduction, (2) review of relevant literature, (3) framework, and (4) methods and procedures. Some graduate schools require in-depth development of these sections, whereas others require a condensed version of the same content. Another approach is that proposals for theses and dissertations be written in a format that can be transformed into a publication. Table 28-1 outlines the content often covered in the chapters of a student quantitative research proposal. TABLE 28-1 Quantitative Research Proposal Guidelines for Students The introductory chapter identifies the research topic and problem and discusses their significance and background. The significance of the problem addresses its importance in nursing practice and the expected generalizability of the findings. The magnitude of a problem is partly determined by the interest of nurses; other healthcare professionals; policy makers; and healthcare consumers at the local, state, national, or international level. You can document this interest with sources from the literature. The background describes how the problem was identified and historically links the problem to nursing practice. Your background information might also include one or two major studies conducted to resolve the problem, some key theoretical ideas related to the problem, and possible solutions to the problem. The background and significance form the basis for your problem statement, which identifies what is not known and the need for further research. Follow your problem statement with a succinct statement of the research purpose or the goal of the study (see Chapter 5) (Martin & Fleming, 2010; Merrill, 2011). The review of relevant literature provides an overview of the essential information that will guide you as you develop your study and includes relevant theoretical and empirical literature (see Table 28-1). Theoretical literature provides a background for defining and interrelating relevant study concepts, whereas empirical literature includes a summary and critical appraisal of previous studies. Here you will discuss the recommendations made by other researchers, such as changing or expanding a study, in relation to the proposed study. The depth of the literature review varies; it might include only recent studies and theorists’ works, or it might be extensive and include a description and critical appraisal of many past and current studies and an in-depth discussion of theorists’ works. The literature review might be presented in a narrative format or in a pinch table that summarizes relevant studies (see Chapter 6) (Pinch, 1995). The literature review shows that you have a command of the current empirical and theoretical knowledge regarding the proposed problem (Merrill, 2011; Offredy & Vickers, 2010). This chapter concludes with a summary. The summary includes a synthesis of the theoretical literature and findings from previous research that describe the current knowledge of a problem (Merrill, 2011). Gaps in the knowledge base are also identified, with a description of how the proposed study is expected to contribute to the nursing knowledge needed for evidence-based practice. A framework provides the basis for generating and refining the research problem and purpose and linking them to the relevant theoretical knowledge in nursing or related fields. The framework includes concepts and relationships among concepts or propositions, which are sometimes represented in a model or a map (see Chapter 7). Middle-range theories from nursing and other disciplines are frequently used as frameworks for quantitative studies, and the proposition or propositions to be tested from the theory need to be identified (Smith & Liehr, 2008). The framework needs to include the concepts to be examined in the study, their definitions, and their link to the study variables (see Table 28-1). If you use another theorist’s or researcher’s model from a journal article or book, letters documenting permission to use this model from the publisher and the theorist or researcher need to be included in your proposal appendices. In some studies, research objectives, questions, or hypotheses are developed to direct the study (see Chapter 8). The objectives, questions, or hypotheses evolve from the research purpose and study framework, in particular the proposition to be tested, and identify the study variables. The variables are conceptually defined to show the link to the framework, and they are operationally defined to describe the procedures for manipulating or measuring the study variables. You also will need to define any relevant terms and to identify assumptions that provide a basis for your study. The researcher describes the design or general strategy for conducting the study, sometimes including a diagram of the design (see Chapter 11). Designs for descriptive and correlational studies are flexible and can be unique to the study being conducted (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000). Because of this uniqueness, the descriptions need to include the design’s strengths and weaknesses. Presenting designs for quasi-experimental and experimental studies involves (1) describing how the research situation will be structured; (2) detailing the treatment to be implemented (Chlan, Guttormson, & Savik, 2011); (3) explaining how the effect of the treatment will be measured; (4) specifying the variables to be controlled and the methods for controlling them; (5) identifying uncontrolled extraneous variables and determining their impact on the findings; (6) describing the methods for assigning subjects to the treatment group, comparison or control group, or placebo group; and (7) exploring the strengths and weaknesses of the design (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). The design needs to account for all the objectives, questions, or hypotheses identified in the proposal. If a pilot study is planned, the design should include the procedure for conducting the pilot and for incorporating the results into the proposed study (see Table 28-1). Your proposal should identify the target population to which your study findings will be generalized and the accessible population from which the sample will be selected. You need to outline the inclusion and exclusion criteria you will use to select a study participant or subject and present the rationale for these sample criteria. For example, a participant might be selected according to the following sample criteria: female, age 18 to 60 years, hospitalized, and 1 day status post abdominal surgery. The rationale for these criteria might be that the researcher wants to examine the effects of a selected pain management intervention on women who have recently undergone hospitalization and abdominal surgery. The sampling method and the approximate sample size are discussed in terms of their adequacy and limitations in investigating the research purpose (Thompson, 2002). A power analysis usually is conducted to determine an adequate sample size to identify significant relationships and differences in studies (see Chapter 15) (Aberson, 2010). Ethical considerations in a proposal include the rights of the subjects and the rights of the agency where the study is to be conducted. Describe how you plan to protect subjects’ rights as well as the risks and potential benefits of your study. Also, address the steps you will take to reduce any risks that the study might present. Many agencies require a written consent form, and that form is often included in the appendices of the proposal. With the implementation of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), healthcare agencies and providers must have a signed authorization form from patients to release their health information for research. You must also address the risks and potential benefits of the study for the institution (Martin & Fleming, 2010; Offredy & Vickers, 2010). If your study places the agency at risk, outline the steps you will take to reduce or eliminate these risks. It is also necessary for you to state that the proposal will be reviewed by the thesis or dissertation committee, university IRB, and agency IRB. Some quantitative studies are focused on testing the effectiveness of an intervention, such as quasi-experimental studies or randomized controlled trials. In these types of studies, the elements of the intervention and the process for implementing the intervention must be detailed (Bulecheck, Butcher, & Dochterman, 2008). You need to develop a protocol that details the elements of the intervention and the process for implementing them (see Chapter 14 and the example quasi-experimental study proposal at the end of this chapter). Intervention fidelity needs to be ensured during a study so that the intervention is consistently implemented to designated study participants (Chlan et al., 2011; Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004). Describe the methods you will use to measure study variables, including each instrument’s reliability, validity, methods of scoring, and level of measurement (see Chapter 16). A plan for examining the reliability and validity of the instruments in the present study needs to be addressed. If an instrument has no reported reliability and validity, you may need to conduct a pilot study to examine these qualities. If the intent of the proposed study is to develop an instrument, describe the process of instrument development (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2010). If physiological measures are used, address the accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity, and error rate of the instrument (Ryan-Wenger, 2010). A copy of the interview questions, questionnaires, scales, physiological measures, or other tools to be used in the study is usually included in the proposal appendices (see Chapter 17). You must obtain permission from the authors to use copyrighted instruments, and letters documenting that permission has been obtained must be included in the proposal appendices. The data collection plan clarifies what data are to be collected and the process for collecting the data. In this plan you will identify the data collectors, describe the data collection procedures, and present a schedule for data collection activities. If more than one person will be involved in data collection, it is important to describe methods used to train your data collectors to ensure consistency. The method of recording data is often described, and sample data recording sheets are placed in the proposal appendices. Also, discuss any special equipment you will use or develop to collect data for the study, and address data security, including the methods of data storage (see Chapter 20). The plan for data analysis identifies the analysis techniques that will be used to summarize the demographic data and answer the research objectives, questions, or hypotheses. The analysis section is best organized by the study objectives, questions, or hypotheses. The analysis techniques identified need to be appropriate for the type of data collected (Grove, 2007). For example, if an associative hypothesis is developed, correlational analysis is planned. If a researcher plans to determine differences among groups, the analysis techniques might include a t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Munro, 2005). A level of significance (α = 0.05, 0.01, or 0.001) is also identified (see Chapters 21 through 25). Often, a researcher projects the type of results that will be generated from data analysis. Dummy tables, graphs, and charts can be developed to present these results and are included in the proposal appendices if required by the guidelines. The researcher might project possible findings for a study and indicate what support or nonsupport of a proposed hypothesis would mean in light of the study framework and previous research findings. The methods and procedures chapter of a proposal usually concludes with a discussion of the study’s limitations and a plan for communication of the findings. Both methodological and theoretical limitations are addressed. Methodological limitations might include areas of weakness in the design, sampling method, sample size, measurement tools, data collection procedures, or data analysis techniques; theoretical limitations set boundaries for the generalization of study findings. The accuracy with which the conceptual definitions and relational statements in a theory reflect reality has a direct impact on the generalization of study findings. Theory that has withstood frequent testing through research provides a stronger framework for the interpretation and generalization of findings. A plan is included for communicating the research through presentations to audiences of nurses, other health professionals, policy makers, and healthcare consumers and publication (see Chapter 27). Qualitative research proposal guidelines are unique for the development of knowledge and theories using various qualitative research methods. A qualitative proposal usually includes the following content areas: (1) introduction; (2) research philosophy and general method; (3) applied method of inquiry; and (4) current knowledge, limitations, and plans for communication of the study findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002; Sandelowski, Davis, & Harris, 1989). Guidelines are presented in Table 28-2 to assist you in developing a qualitative research proposal. TABLE 28-2 Qualitative Research Proposal Guidelines for Students The introduction usually provides a general background for the proposed study by identifying the phenomenon, clinical problem, issue, or situation to be investigated and linking it to nursing knowledge. The general aim or purpose of the study is identified and provides the focus for the qualitative study to be conducted. The study purpose might be followed by research questions that direct the investigation (Munhall, 2012; Offredy & Vickers, 2010). For example, a possible aim or purpose for an ethnographic study might be to “describe the coping processes of Mexican American adults with type 2 diabetes receiving care in a federally funded clinic.” The research questions might focus on the influences of real-world problems, cultural elements, and the clinic environment on the coping processes of these adults. Thus, the study questions might include any of the following: How do Mexican American adults respond to a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes? What is the impact of type 2 diabetes on Mexican American adults and their families over time? What community, clinic, and family types of support exist for Mexican American adults with type 2 diabetes? What does it mean to Mexican American adults to have their diabetes under control? The introduction also includes the evolution of the study and its significance to nursing practice, patients, the healthcare system, and health policy. The discussion of the evolution of the study often includes how the problem developed (historical context), who or what is affected by the problem, and the researcher’s experience with the problem (experiential context). Whenever possible, the significance and evolution of the study purpose needs to be documented from the literature (Munhall, 2012). The significance of a study may include the number of people affected, how this phenomenon affects health and quality of life, and the consequences of not understanding this phenomenon. Marshall and Rossman (2011) identified the following questions to assess the significance of a study: (1) Who has an interest in this domain of inquiry? (2) What do we already know about the topic? (3) What has not been answered adequately in previous research and practice? (4) How will this research add to knowledge, practice, and policy in this area? The introduction section concludes with an overview of the remaining sections that are covered in the proposal. This section introduces the philosophical and conceptual foundation for the qualitative research method (phenomenological research, ethnographic research, grounded theory research, exploratory-descriptive qualitative research, or historical research) selected for the proposed study. The researcher provides a rationale for the qualitative method selected and discusses its ability to generate the knowledge needed in nursing (see Table 28-1). The investigator introduces the philosophy, essential elements of the philosophy, and the assumptions for the specific type of qualitative research to be conducted. The philosophy varies for the different types of qualitative research and guides the conduct of the study. For example, a proposal for a phenomenological study might indicate the purpose of the study is to understand the experience of young and middle-aged women receiving news about a family BRCA 1/2 genetic mutation. “The specific study aims are to (a) describe the experiences of women learning about a family BRCA 1/2 mutation, (b) describe the meaning of genetic risk to female biologic relatives of BRCA 1/2 mutation carriers, and (3) gain an understanding of practical knowledge used in living with risk” (Crotser & Dickerson, 2010, p. 367). Genetic testing has determined that 5% to 10% of breast cancers are caused by inherited gene mutations such as BRCA 1 or BRCA 2. “Heideggerian hermeneutic phenomenology was selected to guide this study.… By listening to the stories of women who lived the experience, HCPs [healthcare providers] will understand the meaning of living with risk through the language used to express their life view (Heidegger, 1975)” (Crotser & Dickerson, 2010, p. 358). Assumptions about the nature of the knowledge and the reality that underlie the type of qualitative research to be conducted are also identified. The assumptions and philosophy provide a theoretical perspective for the study that influences the focus of the study, data collection and analysis, and articulation of the findings. Developing and implementing the methodology of qualitative research require an expertise that some believe can be obtained only through a mentorship relationship with an experienced qualitative researcher. The role of the researcher and the intricate techniques of data collection and analysis are thought to be best communicated through a one-to-one relationship. Thus, planning the methods of a qualitative study requires knowledge of relevant sources that describe the different qualitative research techniques and procedures (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002), in addition to requiring interaction with a qualitative researcher. The proposal needs to reflect the researcher’s credentials for conducting the particular type of qualitative study proposed (see Chapter 12 for details on qualitative research methods). Identifying the methods for conducting a qualitative study is a difficult task because sometimes the specifics of the study design emerge during the study. In contrast to quantitative research, in which the design is a fixed blueprint for a study, the design in qualitative research emerges or evolves as the study is conducted. You must document the logic and appropriateness of the qualitative method and develop a tentative plan for conducting your study. Because this plan is tentative, researchers reserve the right to modify or change the plan as needed during the conduct of the study (Sandelowski et al., 1989). However, the design or plan must be (1) consistent with the philosophical approach, study purpose, and specific research aims or questions; (2) be well conceived; and (3) address prior criticism, as appropriate (Fawcett & Garity, 2009). The tentative plan describes the process for selecting a site and population and the initial steps taken to gain access to the site. Having access to the site includes establishing relationships that facilitate recruitment of the participants necessary to address the research purpose and answer the research questions. For the research question, “How do Mexican American adults cope with a new diagnosis of type 2 diabetes while receiving care in federally funded clinics?” the participants might be identified in a specific clinic or by contacting particular healthcare providers. Although initial contact might be made through a clinic, the interviews and observations might occur in the community, at family gatherings, or in the participants’ homes. The researcher must gain entry into the setting, develop a rapport with the participants that will facilitate the detailed data collection process, and protect the rights of the participants (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Sandelowski et al., 1989). You need to address the following questions in describing the researcher’s role: (1) What is the best setting for the study? (2) How will I ease my entry into the research site? (3) How will I gain access to the participants? (4) What actions will I take to encourage the participants to cooperate? (5) What precautions will I take to protect the rights of the participants and to prevent the setting and the participants from being harmed? You need to describe the process you will follow to obtain informed consent and the actions you will take to decrease study risks. The sensitive nature of some qualitative studies increases the risk for participants, which makes ethical concerns and decisions a major focus of the proposal (Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002). The primary data collection techniques used in qualitative research are observation and in-depth interviewing. Observations can range from highly detailed, structured notations of behaviors to ambiguous descriptions of behaviors or events. The interview can range from structured, closed-ended questions to unstructured, open-ended questions (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012). You need to address the following questions when describing the proposed data collection process: (1) What data will be collected? For example, will the data be field notes from memory, audio recordings of interviews, transcripts of conversations, DVDs of events, or examination of existing documents? (2) What techniques or procedures will the research team use to collect the data? For example, if interviews are to be conducted, will a list of the proposed questions be included in the appendix? (3) Who will collect data and provide any training required for the data collectors? (4) Where will sources of data be located? In historical research, data are collected through an exhaustive review of published and unpublished literature. (5) How will the data be recorded and stored? The methods section also needs to address how you will document the research process. For example, you might keep a research journal or diary during the course of the study. These notes can document the day-to-day activities, methodological events, decision-making procedures, and personal notes about the informants. This information becomes part of the audit trail that you can provide to ensure the quality of the study (Miles & Huberman, 1994; Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002). The methods section of the proposal also includes the analysis techniques and the steps for conducting these techniques. In qualitative research, data collection and analysis often occur simultaneously. The data are usually in the form of notes, digital files, audio recordings, DVDs, and other material obtained from observation, interviews, and completing questionnaires. Through qualitative analysis techniques, these data are organized to promote understanding and determine meaning (see Chapter 12) (Patton, 2002). Researchers also need to identify software programs they plan to use for data analysis. This section of the proposal summarizes and documents all relevant literature that was reviewed for the study. Similar to quantitative research, qualitative studies require a literature review to provide a basis for the study purpose and to clarify how this study will expand nursing knowledge (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012). This initial literature review is often conducted to establish the significance of the study and to develop research questions to guide the study. In phenomenological and grounded theory research, an additional literature review is usually conducted toward the end of the research project. The findings from a phenomenological study are compared and combined with findings from the literature to contribute to the current knowledge of the phenomenon. In grounded theory research, the literature is used to explain, support, and extend the theory generated in the study (Glaser & Strauss, 1965). In all types of qualitative studies, the findings obtained are examined in light of the existing literature (see Chapter 4). Conclude your proposal by describing how you plan to communicate your findings to various audiences through presentations and publications. Often, a realistic budget and timetable are provided in the appendix. A qualitative study budget is similar to a quantitative study budget and includes costs for data collection tools, software, and recording devices; consultants for data analysis; travel related to data collection and analysis; transcription of recordings; copying related to data collection and analysis; and developing, presenting, and publishing the final report. However, one of the greatest expenditures in qualitative research is the researcher’s time. Develop a timetable to project how long the study will take; often a period of 2 years or more is designated for data collection and analysis (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002). You can use your budget and timetable to make decisions regarding the need for funding. Excellent websites have been developed to assist novice researchers in identifying an idea for qualitative study and developing a qualitative research proposal and reports (see www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/qualres.html). The Office of Behavior and Social Sciences Research within the National Institutes of Health has a website to assist researchers in developing qualitative and quantitative research proposals for funding (http://grants.nih.gov/grants/writing_application.htm). You can use these websites and other publications to promote the quality of your qualitative research proposal. The quality of a proposal is based on the potential scientific contribution of the research to nursing knowledge; the research philosophy guiding the study; the research methods; and the knowledge, skills, and resources available to the investigators (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012; Patton, 2002).

Writing Research Proposals

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Writing a Research Proposal

Developing Ideas Logically

Determining the Depth of a Proposal

Identifying Critical Points

Developing an Esthetically Appealing Copy

Content of a Research Proposal

Content of a Student Proposal

Content of a Quantitative Research Proposal

Chapter I

Introduction

A. Background and significance of the problem

B. Statement of the problem

C. Statement of the purpose

Chapter II

Review of Relevant Literature

A. Review of theoretical literature

B. Review of relevant research

C. Summary

Chapter III

Framework

A. Development of a framework

(Develop a map of the study framework, define concepts in the map, describe relationships or propositions in the map, indicate the focus of the study, and link concepts to study variables)

B. Formulation of objectives, questions, or hypotheses

C. Definitions (conceptual and operational) of study variables

D. Definition of relevant terms

Chapter IV

Methods and Procedures

A. Description of the research design

(Model of the design, strengths and weaknesses of the design validity)

B. Identification of the population and sample

(Sample size, use of power analysis, sample criteria, and sampling method including strengths and weaknesses)

C. Selection of a setting

(Strengths and weaknesses of the setting)

D. Presentation of ethical considerations

(Protection of subjects’ rights and university and healthcare agency review processes)

E. Description of the intervention if appropriate for the type of study

(Provide a protocol for implementing the intervention, detail who will implement the intervention, and describe how intervention fidelity is ensured)

F. Selection of measurement methods

(Reliability, validity, scoring, and level of measurement of the instruments as well as plans for examining reliability and validity of the instruments in the present study; precision and accuracy of physiological measures)

G. Plan for data collection

(Data collection process, training of data collectors if appropriate, schedule, data collection forms, and management of data)

H. Plan for data analysis

(Analysis of demographic data; analyses for research objectives, questions, or hypotheses; level of significance if appropriate; and other analysis techniques)

I. Identification of limitations

(Methodological and theoretical limitations)

J. Discussion of communication of findings

References

Include references cited in the proposal and follow APA (2010) format

Appendices

Presentation of a study budget and timetable

Introduction

Review of Relevant Literature

Framework

Methods and Procedures

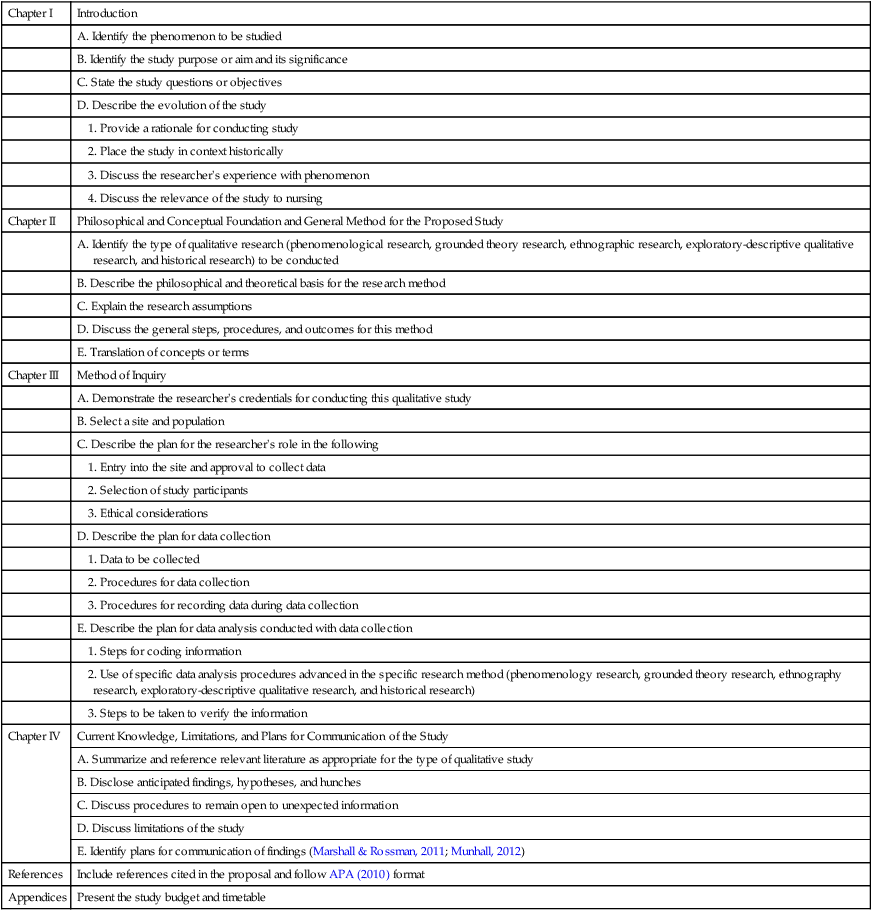

Content of a Qualitative Research Proposal

Chapter I

Introduction

A. Identify the phenomenon to be studied

B. Identify the study purpose or aim and its significance

C. State the study questions or objectives

D. Describe the evolution of the study

1. Provide a rationale for conducting study

2. Place the study in context historically

3. Discuss the researcher’s experience with phenomenon

4. Discuss the relevance of the study to nursing

Chapter II

Philosophical and Conceptual Foundation and General Method for the Proposed Study

A. Identify the type of qualitative research (phenomenological research, grounded theory research, ethnographic research, exploratory-descriptive qualitative research, and historical research) to be conducted

B. Describe the philosophical and theoretical basis for the research method

C. Explain the research assumptions

D. Discuss the general steps, procedures, and outcomes for this method

E. Translation of concepts or terms

Chapter III

Method of Inquiry

A. Demonstrate the researcher’s credentials for conducting this qualitative study

B. Select a site and population

C. Describe the plan for the researcher’s role in the following

1. Entry into the site and approval to collect data

2. Selection of study participants

3. Ethical considerations

D. Describe the plan for data collection

1. Data to be collected

2. Procedures for data collection

3. Procedures for recording data during data collection

E. Describe the plan for data analysis conducted with data collection

1. Steps for coding information

2. Use of specific data analysis procedures advanced in the specific research method (phenomenology research, grounded theory research, ethnography research, exploratory-descriptive qualitative research, and historical research)

3. Steps to be taken to verify the information

Chapter IV

Current Knowledge, Limitations, and Plans for Communication of the Study

A. Summarize and reference relevant literature as appropriate for the type of qualitative study

B. Disclose anticipated findings, hypotheses, and hunches

C. Discuss procedures to remain open to unexpected information

D. Discuss limitations of the study

E. Identify plans for communication of findings (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012)

References

Include references cited in the proposal and follow APA (2010) format

Appendices

Present the study budget and timetable

Introduction

Philosophical and Conceptual Foundation and General Methods for the Proposed Study

Method of Inquiry

Current Knowledge Base, Limitations, and Plans for Communication of the Study

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Writing Research Proposals

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access