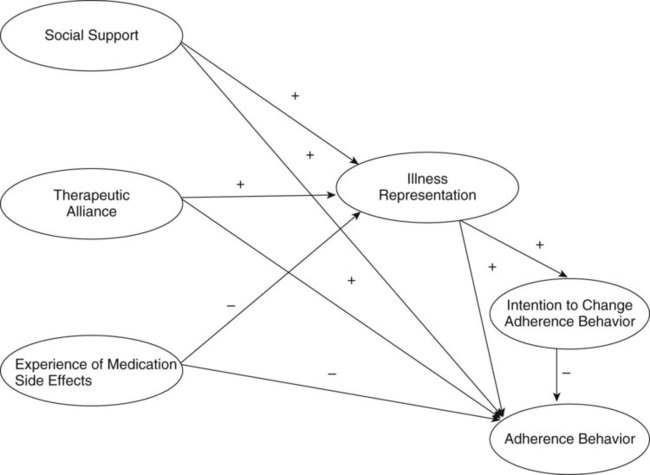

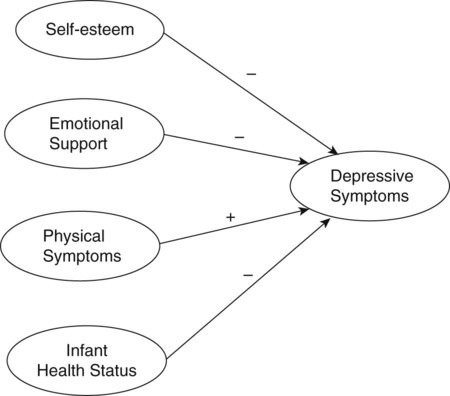

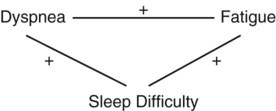

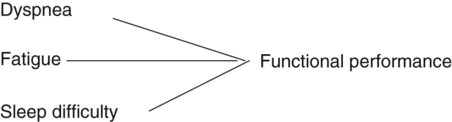

1. Identify the elements or characteristics of variable X in a selected population (identification). 2. Describe variable X in a selected population (description). 3. Determine the difference between groups 1 and 2 or to compare groups 1 and 2 on variable X in a selected population (difference). 4. Examine the relationship between variables X and Y in a selected population (relational). 5. Determine whether certain independent variables are predictive of a dependent variable in a selected population (prediction). The objectives or aims in quantitative studies are developed on the basis of the research problem and purpose to clarify the study goals, variables, and population. The following excerpts, from a descriptive study of the symptom management strategies used by elderly patients after coronary artery bypass surgery (CABS), demonstrate the logical flow from research problem (including the problem significance, background, and statement) and purpose to research aims (Schulz, Zimmerman, Pozehl, Barnason, & Nieveen, 2011). “A major component of nursing care after coronary artery bypass surgery (CABS) is focused on educating patients to recognize and manage postoperative symptoms [problem significance]. The symptoms commonly experienced have been well documented in the literature and include sleep disturbances (Tranmer & Parry, 2004; Zimmerman, Barnason, Nieveen, & Schmaderer, 2004), fatigue (Tranmer & Parry, 2004; Zimmerman et al., 2004), swelling (Tranmer & Parry, 2004; Zimmerman et al., 2004), shortness of breath (SOB), appetite problems, and chest and leg incision pain (Zimmerman et al., 2004) [problem background]. Although much has been done to document postoperative symptoms, very little has been done to describe the strategies that patients use to manage these symptoms [problem statement].” (Schulz et al., 2011, pp. 65-66) In this example, the problem provides a basis for the purpose, and the aims evolve from the purpose to clearly focus the conduct of the study. The first aim was focused on identification of the categories of symptom management strategies (variable) used by older adults (population) 3 and 6 weeks after CABS (hospital and home settings). The study participants were recruited from four Midwestern hospitals, but the majority of data collection took place in the participants’ homes. The second aim was focused on description of the older adults’ symptom management strategies (variable) used. The third objective was focused on comparison of or differences in patients’ reported symptom management strategies and current evidence-based guidelines developed by the American Heart Association. Schulz et al. (2011, p. 65) found, “Three weeks after surgery, the most frequently used strategies were rest to manage shortness of breath (53%) and fatigue (53%), medications for incision pain (24%), and repositioning for swelling (35%) and sleep disturbance (18%). Overall, fewer patients experiencing sleep disturbances (39%), incision pain (39%), swelling (46%), and appetite problems (17%) reported using a strategy to manage their symptoms.” Thus, the researchers stressed the importance of nurses’ education of patients about symptom identification and effective management strategies to improve recovery following CABS. Many qualitative studies are guided by the study purpose and do not include research objectives or questions. However, some qualitative researchers do develop objectives to guide selected studies. The objectives in qualitative studies usually have a broader focus and include more abstract and complex variables or concepts than those in quantitative studies (Munhall, 2012). An ethnographic study by Happ, Swigart, Tate, Hoffman, and Arnold (2007) included objectives to direct their investigation of patients’ involvement in health-related decisions during prolonged critical illness, as shown by the following excerpts. In this ethnographic study, the problem statement indicated that inadequate research had been conducted on patient involvement in health-related decisions during critical illness, which provided a basis for the study purpose. All four objectives focused on detailed descriptions of the study variables: (1) characteristics of patients undergoing PMV, (2) health-related decision making of these patients, (3) how patient involvement in decision making occurred, and (4) extent of patient decision making. The findings from this study indicated that families, advanced practice nurses, and physicians were engaging critically ill patients in decision making whenever possible. However, most of the time the patients could not make independent decisions but were able to share decision making with their families and clinicians. These findings emphasize how important it is for families and clinicians to include critically ill patients in health-related decisions at whatever level possible (Happ et al., 2007). 1. What are the elements or characteristics of variable X in a selected population (identification)? 2. How is variable X described by a selected population (description)? 3. Is there a difference between groups 1 and 2 regarding variable X (difference)? 4. What is the relationship between variables X and Y in a selected population (relational)? 5. Are independent variables W, X, and Y predictive of dependent variable Z (prediction)? Delaney, Apostolidis, Lachapelle, and Fortinsky (2011, p. 285) conducted a comparative descriptive study to examine “home care nurses’ knowledge of evidence-based education topics for management of heart failure.” The following excerpts from this study demonstrate the flow from research problem and purpose to research questions. Question 1 focused on description of the home care nurses’ (population) knowledge about HF (variable). Question 2 focused on determining differences in the nurses’ knowledge on the basis of educational level and years of work experience (demographic variables). Question 3 focused on description of the nurses’ self-reported knowledge needs (variable) in managing patients with HF. Delaney et al. (2011) found that home care nurses were limited in their evidence-based knowledge for managing HF. There were no significance differences in the nurses’ knowledge and their educational level and years of experience. The researchers concluded that the home care nurses needed educational programs focused on HF patient management to improve the quality of patient education they could provide. The questions in qualitative studies are often limited in number, have a broad focus, and include variables or concepts that are more complex and abstract than those in quantitative studies. Marshall and Rossman (2011) noted that the questions in qualitative research either might be theoretical ones, which can be studied with different populations or in a variety of sites, or could be focused on a particular population or setting. Hudson et al. (2010) conducted an exploratory-descriptive qualitative study to examine the health-seeking challenges perceived by homeless young adults. The problem, purpose, and research questions used to direct this study are presented in the following excerpts. The first study question focused on developing a description of the homeless young adults’ (population) perspectives on facilitators and barriers to receiving health care (research variables). The second question focused on identifying and describing how young-adult-centered healthcare programs can be improved (research variable). The study’s “identified themes were failing access to care based on perceived structural barriers (limited clinic sites, limited hours of operation, priority health conditions, and long wait times) and social barriers (perception of discrimination by uncaring professionals, law enforcement, and society in general…)” (Hudson et al., 2010, p. 212). The researchers also gained insights into the programmatic and agency resources that are needed to promote health-seeking behaviors by homeless young adults. A hypothesis is the formal statement of the expected relationship or relationships between two or more variables in a selected population. The hypothesis translates the problem and purpose into a clear explanation or prediction of the expected results or outcomes of the study (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). This section describes the purpose, sources, and types of hypotheses that are commonly developed by researchers. In addition, the process for developing and testing hypotheses in nursing studies is described. The purpose of a hypothesis is similar to that of research objectives and questions. A hypothesis (1) specifies the variables you will manipulate or measure, (2) identifies the population you will examine, (3) indicates the type of research, and (4) directs the conduct of your study. Hypotheses direct the conduct of a study by influencing the study design, sampling technique, data collection and analysis methods, and interpretation of findings. Hypotheses differ from objectives and questions by predicting the outcomes of a study. Study hypotheses are used to organize the results section of a study, and the results indicate support or nonsupport of each hypothesis. Hypothesis testing allows us to generate knowledge by testing theoretical statements or relationships that were identified in previous research, proposed by theorists, or observed in practice (Chinn & Kramer, 2008; Fawcett & Garity, 2009 You could conduct a literature review to identify a theory that supports this relationship. For example, Fagerhaugh and Strauss (1977) developed a theory of pain management and identified the following relationship or proposition: As expressions of pain increase, pain management increases. The researchers developed this proposition through the use of grounded theory research. Additional testing is necessary to determine its usefulness in describing how patients express pain and how that pain is managed in a variety of practice situations. On the basis of theory and clinical observation, the following hypothesis might be formulated: The more frequently a hospitalized patient verbalizes perceptions of pain, the greater the administration of analgesic medications by healthcare providers. Some hypotheses are initially generated from relationships expressed in a theory, when the intent of the researcher is to test a theory. Usually, middle-range theories are tested in research, and a proposition or relationship from the theory provides the basis for the generation of one or more study hypotheses (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Smith & Liehr, 2008). For example, Rungruangsiripan, Sitthimongkol, Maneesriwongul, Talley, and Vorapongsathorn (2011) tested the relationships in the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representation (Diefenbach & Leventhal, 1996) to examine the factors affecting medication adherence in individuals with schizophrenia. Figure 8-1 contains the framework model for this study based on the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representation, which has three stages: sources of information, illness representation, and coping. “Sources of information included social support variable, therapeutic alliance variable, and experience of medication side effects variable. Coping consisted of intention to change adherence behavior and adherence behavior” (Runguangsiripan et al., 2011, p. 272). This model shows the direct and indirect relationships among the concepts that provide a basis for the study hypotheses. A direct relationship is when one concept links to another concept without an intervening concept. For example, the concept of social support is linked directly to illness representation. In an indirect relationship, one concept is linked to another concept through an intervening third concept. For example, the concept experience with medication side effects is indirectly linked to the concept intention to change adherence behavior through the concept of illness representation (see Figure 8-1). The Rungruangsiripan et al. (2011) study set the following hypotheses: These hypotheses were formulated to test the propositions or relationships from the Common-Sense Model of Illness Representation (see Figure 8-1). The researchers found that “therapeutic alliance and the experience of medication side-effects enhanced illness representation, which in turn led to an intention to change adherence behavior. Social support did not alter illness representation or adherence behavior” (Rungruangsiripan et al., 2011, p. 269). Illness representation is the patients’ perception of their schizophrenia and their ability to cope with the illness. Patients with a clear perception of their schizophrenia have strong intentions to change their adherence behaviors. Thus, mental health nurses need to promote the patients’ understanding of their schizophrenia illness to enhance their adherence to their medications. Reviewing the research literature and synthesizing findings from different studies can also be used to generate hypotheses. For example, Ross, Sawatphanit, Mizuno, and Takeo (2011) synthesized the findings from studies to identify the factors that predict depressive symptoms in postpartum women who are HIV-positive. They developed a conceptual framework for their study that is presented in Figure 8-2. The researchers “hypothesized that depressive symptoms are negatively related to self-esteem, emotional support, and infant health status but positively associated with physical symptoms” (Ross et al., 2011, p. 37). Ross et al. (2011) found that self-esteem and infant health status were significant predictors of postpartum women’s depressive symptoms but physical symptoms and emotional support were not. The study results indicated that 74.1% of the HIV-positive postpartum women had symptoms of depression, and the researchers encouraged nurses to examine the self-esteem and infant health status of such women to increase identification of episodes of depression. The researchers also recommended further research to identify additional factors that might be predictive of depression in HIV-positive postpartum women. Thus, two relationships, those of self-esteem and infant health status to depressive symptoms, were supported in the framework model (see Figure 8-2). However, the other relationships, those of emotional support and physical symptoms to depressive symptoms, were not supported in this study. Additional research is needed to increase understanding of the factors that might be predictive of depression in postpartum women who are HIV-positive. 1. Variable X is related to or associated with variable Y in a selected population. (Predicts a relationship between two variables but does not indicate the type of relationship.) 2. An increase in variable X is related to an increase in variable Y, or variable X is positively related to variable Y in a selected population. (Predicts a positive relationship.) 3. A decrease in variable X is related to a decrease in variable Y in a selected population. (Predicts a positive relationship.) 4. An increase in variable X is related to a decrease in variable Y, or variable X is negatively related to variable Y in a selected population. (Predicts a negative or inverse relationship.) 5. Variables X and Y are predictive of variable Z in a study. (The independent variables X and Y are used to predict the dependent variable Z in a predictive correlational study.) Associative hypotheses identify relationships among variables in a study but do not indicate that one variable causes an effect on another variable. Researchers state associative hypotheses when the focus of their study is to examine relationships and not to determine cause and effect. For example, Reishtein (2005) conducted a predictive correlational study to examine the relationships between symptoms and functional performance in patients with chronic obstructed pulmonary disease (COPD). Reishtein developed the following associative hypotheses to guide the study:

Objectives, Questions, Hypotheses, and Study Variables

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Formulating Research Objectives or Aims

Formulating Objectives or Aims in Quantitative Studies

Research Problem

Formulating Objectives or Aims in Qualitative Studies

Formulating Research Questions

Formulating Questions in Quantitative Studies

Formulating Questions in Qualitative Studies

Formulating Hypotheses

Purpose of Hypotheses

Sources of Hypotheses

Types of Hypotheses

Associative versus Causal Hypotheses

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Objectives, Questions, Hypotheses, and Study Variables

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access