Paula Erwin Toth, MSN, RN, CWOCN, CNS

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- describe different types of tubes and drains

- state the etiology of fistulae

- discuss management options for drains, tubes, and fistulae.

Tube, drain, and fistula care may seem out of place in a wound care text. However, the realities of clinical practice sometimes dictate that a wound care clinician be consulted in the management of these special patients. In fact, it is not uncommon for people with wounds to have an assortment of concomitant conditions that include a fistula or the use of tubes and drains. Wound care is a science; drain, tube, and fistula management is an art based in science. As with all aspects of patient care, a holistic approach is essential.

Tubes and Drains

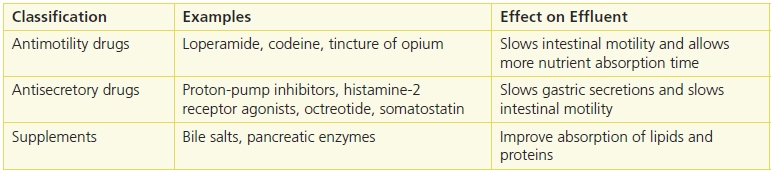

The purposes of tubes and drains include the promotion of drainage from a wound or body cavity, decompression, lavage, and medication administration. Placement of tubes and drains will depend on the type, location, and purpose of the tube or drain being used. Determining a management plan starts with an assessment of the type of tube being used and the manufacturer’s guidelines for care; the location of the tube, including any associated skin folds that can impede the stability of the device; and a medical record review to determine the internal location and purpose of the tube and how well the device is functioning.1 Depending on the type, purpose, and location of the tube or drain, the insertion process will be facilitated by computed tomography, fluoroscopic illumination, or endoscopic guidance (Table 19-1). In the case of open or laparoscopic surgery, the tube or drain generally is placed during the procedure.1

Table 19-1 Categories of Tubes and Drains

Premarking the drain site prior to insertion is sometimes helpful. With an enteral feeding tube, for example, premarking the drain site minimizes the possibility of the tube residing within a skin fold or crease. Tubes situated on a level plane of skin are easier to stabilize and manage.

A gap often exists in patient and family education regarding drains and tubes. Most people are aware of what to expect as far as an incision is concerned, but the presence of a tube or drain is unanticipated and unwelcomed. Preparing the patient for the potential outcome of tube or drain placement reduces anxiety and gives the patient the opportunity to plan ahead1 (Table 19-2).

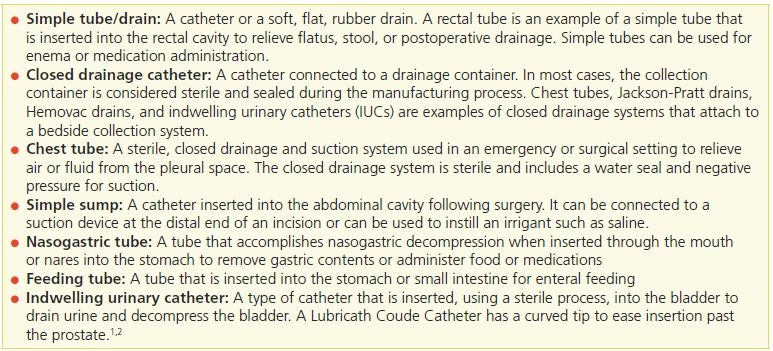

Table 19-2 Common Types of Tubes

Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

Tell the patient and family the location and the number of tubes and drains that might be needed after surgery or to treat their medical condition.

Types of Tubes and Drains

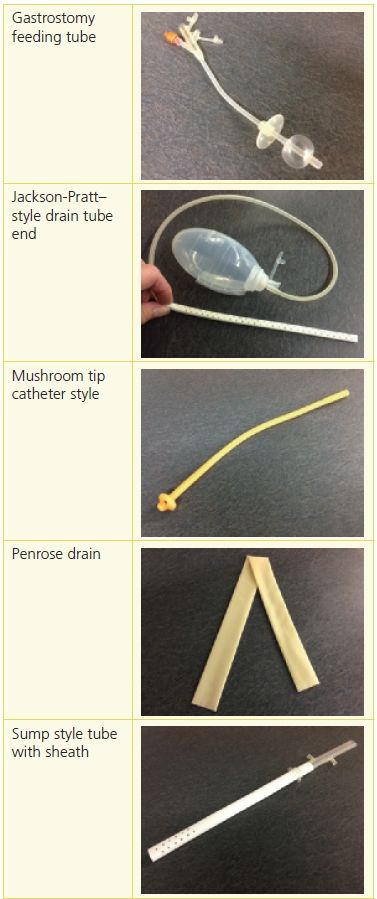

Feeding Tubes

Patients who require enteral feeding are debilitated by disease, traumatic injury, extensive surgery, or malnourishment. Enteral feeding following a surgical procedure in which the patient is unable to take food by mouth is desirable to treat and prevent nutritional deficits and prevent atrophy of mucosal villi in the small intestine.2 Types of enteral feeding systems include nasogastric, gastrostomy, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG), and jejunostomy. Tubes can be placed using several methods, including surgical, endoscopic, radiological, or manual by way of the nares (Table 19-3).

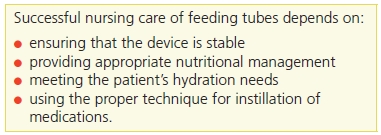

Table 19-3 Nursing Care of Feeding Tubes

Nasogastric Tubes

Nasogastric tubes are inserted manually and are the least stable of the enteral feeding options. The procedure involves selecting the appropriate feeding tube, measuring the patient’s anatomy to determine the length of insertion, lubricating the tube, placing the patient in a high Fowler’s position, having the patient swallow water (if responsive) during the insertion process, and educating the patient about the procedure. Be sure to maintain tube stability at the nares used for insertion, and check throughout the insertion procedure and before instilling the liquid feeding that the tube does indeed end distally in the stomach.

Gastrostomy Tubes

Gastrostomy tubes (G tubes) are surgically inserted directly into the stomach and exit at the anterior abdominal wall. This type of procedure allows for proximal decompression with simultaneous distal enteral feeding. A number of commercially manufactured G tubes are available for use. The typical design includes a disk to stabilize the tube exteriorly against the abdominal wall and a balloon tip at the distal end to ensure internal stability.2

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy Tubes

PEG tubes are inserted directly into the abdominal wall using an endoscope. The tube exits proximally at the abdominal wall. The main purpose of PEG tubes is to treat and prevent nutritional deficits associated with chronic illness complications, extensive surgery, and abdominal trauma. Tube stabilization is achieved with internal and external bumpers placed along the abdominal wall.2

Jejunostomy Tubes

Jejunostomy tubes are surgically or endoscopically inserted directly into the jejunum for the purpose of long-term enteral feeding in patients who are at risk for aspiration or for patients with esophageal, gastric, or duodenal disease processes. Tube stability is achieved with internal and external bumpers.2

Biliary Tubes

Biliary tubes are used to relieve obstruction and facilitate drainage from the bile ducts of the liver. The catheter is inserted into the liver and bile duct either as part of a surgical procedure or via fluoroscopy using contrast and a guidewire. Catheter holes are positioned above and below the obstruction. Biliary tract drains include cholecystectomy tubes, percutaneous drains of the biliary tract, T tubes, and endoscopically placed nasobiliary tubes. Nursing management of biliary tubes includes maintaining tube stability, containing the effluent (output), caring for the skin around the tube, and monitoring output.2

Esophagostomy Tubes

During esophagostomy, which involves surgical resection of the diseased part of the esophagus, the proximal end of the esophagus is brought to skin level and forms a stoma. The stoma is generally flush with the skin and located lateral to the trachea, resulting in an uneven surface that is difficult to pouch. Creative management solutions involve skin preparation and the use of moldable skin barriers attached to a pouching system to contain the drainage. A decompression tube can be added to aid patient comfort in cases of intractable nausea and vomiting.2

Indwelling Urinary Catheters

Indwelling urinary catheters (IUCs) have gained much attention in the literature and with regulatory agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) as a cause of increased cost to care and increase risk of infection.3,4 Acute care hospitals, long-term care, and rehabilitation centers have also recognized the need to develop policies aimed at using IUCs more judiciously and for shorter periods of time to reduce the potential damage of IUCs on the lower urinary tract, reduce catheter-related sepsis, and promote urinary continence strategies.4

IUCs are used to monitor urinary output, manage urinary retention, decompress the bladder following surgery, and manage wounds complicated by urinary incontinence. They are used occasionally for long-term management of urinary incontinence.1,5–7 A large variety of IUCs are available for use, including catheters made from latex or silicone and catheters coated with hydrogel, Teflon, or a silver alloy.3 Common IUC properties include a double lumen, a balloon tip at the proximal end to maintain placement in the bladder, a distal end that will accommodate connection to a closed drainage system, and sufficient length to extend from the bladder and through the urethra to connect to a closed drainage system. The double lumen allows for balloon inflation and deflation as well as urinary drainage.

IUCs are one of the most frequent causes of nosocomial infection in acute care settings. Selecting the appropriate IUC begins with assessment of the patient. Considerations include allergies (such as latex) that will preclude the use of some types of catheters, the length of time the IUC is expected to be in place, and the mobility of the patient. In general, the smallest French size needed should be selected because the elastic urinary mucosa will conform to the catheter. Using larger-French-size catheters can cause erosion of the uroepithelium and result in leakage of urine and permanent damage to the urethra. The newer silver alloy–coated catheters are intended to reduce bacterial growth. A review of the literature demonstrates limited effectiveness in the reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) with short-term IUC use.1,5 Nursing management of IUCs incorporates measures to prevent infection and limit the length of time the catheter is used.1,5–7 The longer the catheter is in place, the higher the risk will be for bacteria to infiltrate the bladder. Most IUCs should be considered for short-term use (20 to 30 days). Local care of the urinary meatus with soap and water on a daily basis along with use of a closed drainage system has been shown to reduce bacterial migration as well as provide an opportunity for the nurse to monitor the condition of the perineal area.1,6,7 Balloon size and inflation have also been discussed in the literature as important aspects of care. The purpose of the balloon is to stabilize the catheter in the bladder. For most adults, this can be achieved with a 5-mL balloon. Larger balloons (up to 30 mL) are manufactured with the intent of providing hemostasis by adding internal pressure following prostatectomy.1,5–7 Additional nursing management strategies center on monitoring the patient for leakage (usually a result of bladder spasms), catheter-associated pain or discharge, and the color, odor, and amount of urine. Assess the patient for symptoms of CAUTI. Anchoring the catheter to the internal area of the patient’s leg will provide additional stabilization and comfort and reduce the risk of accidental removal.1,5,7

Practice Point

Practice Point

Presenting symptoms of CAUTI include fever, chills, diaphoresis, hematuria, and pain (flank and suprapubic).

Nephrostomy Tubes

Nephrostomy tubes are used to relieve obstructive uropathy of the lower urinary tract. They are placed into the renal pelvis of the kidney at the flank using fluoroscopy in interventional radiology with the patient under conscious sedation.2 Nephrostomy tubes provide temporary or permanent drainage for the urinary collection system. They also provide for insertion of stents, divert urine from urethral fistulae, and allow access for kidney stone removal or biopsy.

Nursing Plan of Care

The nursing plan of care for patients with tubes or drains is developed using a holistic approach, which requires a thorough understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the body systems involved as well as the rationale for the selected tube or drain. Knowledge of these factors combined with assessment of the external factors affecting the patient provides a clear picture of what is needed to manage patient needs. External factors include the physical environment of care, socioeconomic issues, family support, and psychosocial concerns.1,2,5–7 A comprehensive plan of care involves an interdisciplinary team approach that incorporates the reasons for the IUC with daily assessment and care of the skin around the tube or drain, early identification of problems, and removing the IUC when no longer required. Patient and family education is also an important aspect of care and includes nursing care needs along with signs of complications.

Interdisciplinary Team Approach

Achieving a comprehensive plan of care to meet the complex needs of patients with tubes or drains requires a collaborative team. This team can include, but is not limited to, the primary care physician, surgeon, radiologist, gastroenterologist, physical therapist, social worker, case manager, registered dietitian, primary nurse, and wound, ostomy, and continence (WOC) nurse. The care plan needs to include interventions aimed at tube stabilization, containment and measurement of effluent, skin management, nutritional support, patient mobilization, and effective communication practices with the medical team.1,2

The registered dietitian plays a vital role on the interdisciplinary team because he or she is educationally prepared to determine the appropriate formula for enteral feeding, hydration needs, and management of diarrhea. Nurses caring for patients receiving enteral tube feedings need to develop policies that include monitoring hydration, assessing for patient tolerance by evaluating gastric aspirates, maintaining the stability of the device, and engaging with the physician and pharmacist for optimal medication management.2

Education

Education and discharge planning are the next step in the plan of care. Each member of the collaborative team will contribute to the education needs of the patient or caregiver; understanding these needs in turn helps the team to determine discharge needs.2 Education should be based on the principles of adult learning and include an explanation of the purpose of the drain or tube, the need for and how to stabilize the tube, management of the containment device, skin care, any feeding schedules and procedures, and the signs and symptoms of complications. Determine whether the complexity of care is beyond the ability of the patient and, if so, ascertain whether a caregiver is willing and able to provide support.2 The details of care should be demonstrated, reviewed, and evaluated, and written instructions should be provided. What, if any, support will be needed after discharge? How stable is the patient? Is discharge to the home a realistic option?

Skin Care Around the Tube

The skin around the insertion site should be assessed daily for signs of skin breakdown, infection, or excoriation. Leakage of gastric contents onto the skin is not uncommon; when it occurs, the tube must be examined for leaks and stabilized to prevent movement in and out of the abdomen. If the tube migrates or stretches, leakage of gastric contents from the puncture site can damage the skin. For the first week after tube placement, the insertion site and external retention device should be cleaned with normal saline. Half-strength hydrogen peroxide can be used to remove crusts. After the first week, the stoma site and the area beneath the external retention device should be cleaned daily with a pH-balanced skin cleanser. pH-balanced solutions do not damage the skin, leave little residue, and protect the skin without changing its pH.

G tubes should be checked for their ability to be moved in and out of the abdominal wall; ¼ inch (0.5 cm) of movement is normal. If the tube cannot be moved even slightly, notify the physician. Often called “buried bumper syndrome,” the inability to move the tube may indicate that it has become embedded in the tissues and can erode into the stomach wall. G tube insertion sites should not be packed tightly with dressings between the tube and skin. Occasionally, hypergranulation tissue will develop at the puncture site. This tissue is not harmful and usually results from irritation from the tube.

Tube blockage is common with crushed medication, inadequate flushing (particularly with nasojejunal tubes, which tend to be longer and of finer bore), or precipitation of protein in the feeding. To avoid a clogged feeding tube, thoroughly flush enteral feeding devices every 4 to 6 hours during continuous feedings and whenever feedings are on hold, before and after administration of feedings and medications, and after checking residuals. Always use a large syringe (30 to 60 mL) for flushing to prevent rupture of the tube. Irrigate the tube with 20 to 30 mL of tepid water. Tubes can generally be unblocked using a variety of solutions, such as water, carbonated soda, pancreatic enzymes, or commercially available products. No fluid has been found to be superior to water for maintaining patency. If the feeding tube has a Y-port connector, flush through the side port. Otherwise, disconnect the feeding infusion device and flush directly into the tube.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Medications that can be administered in liquid form are best suited for enteral feeding tubes. Water flushes between medications and feedings will help prevent tube obstruction.

Enterocutaneous Fistulae

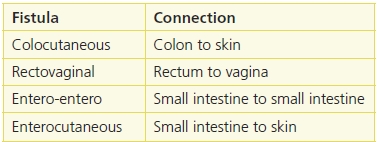

An enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) is an abnormal connection between two epithelial surfaces.8,9 This connection can occur between two internal organs or can lead from an internal organ to a body surface. The physiological origin and exit point of the fistula are the basis for naming and evaluating a fistula (Table 19-4).

Table 19-4 Types of Fistulae

Although ECFs are not common, certain diseases or conditions will predispose a person to develop an ECF. Inflammatory bowel disease, such as Crohn’s disease, can cause spontaneous fistula development and increase the risk of a postoperative fistula.8–10 These patients require medical support and regular monitoring for complications. Other predisposing factors include traumatic abdominal injury, peritonitis, small bowel obstruction, malnutrition (especially prior to abdominal surgery), the presence of devascularized tissue, and radiation enteritis.8 Many times, these conditions can result in a large, deep abdominal wound with or without exposure of the bowel wall.

An ECF is one of the most challenging complications for the nurse to manage and devastating for the patient. Fluid and electrolyte imbalances, erosion of adjacent skin secondary to the corrosive nature of the effluent, malnutrition, dehydration, and the psychosocial well-being of the patient all require ongoing monitoring and evaluation for the best outcomes. The mortality rate for patients with ECF ranges from 12% to 25%, usually the result of sepsis, malnutrition, and dehydration.7–11 The cost to managing a fistulae, including diagnostic tests, nutritional support, medical supplies, and medical care, is estimated at nearly $262,140.12 With the current reimbursement of care environment, it is important to identify early on and provide nutritional, nursing, and medical support for the patient at risk of developing fistulae. Advances in nutritional support options, antibiotics, containment devices, and managing fluid and electrolyte balance have contributed to improved care and patient recovery from this type of event.11

Classification of ECFs

ECFs can be classified in a number of ways based on the type and amount of effluent present, the anatomy involved, and the complexity of the tract.8 Classifying the fistula provides assessment and documentation parameters as well as clues to interventions aimed at both stabilizing and managing the patient. A simple fistula has a direct tract without an abscess. A type I complex fistula is associated with abscesses and multiple organ involvement.8 Type II complex fistulae open into the base of an open wound; these are among the most challenging and devastating fistulae to care for.8

The amount of effluent is also important. Low-volume fistulae are defined by drainage amounts of less than 500 mL in a 24-hour period, while high-volume fistulae have drainage in excess of 500 mL over 24 hours.9,11 Effective monitoring and measuring of ECF output are critical in managing fluid balance. Generally, the more proximal the fistula is located, the higher the amount of output will be.6,9,11

The color and consistency of the effluent provide clues to the origin of the ECF. Gastric drainage is clear to light yellow-green in color with a watery consistency; the pH will be about 3.0.8 Biliary drainage is a gold to deep green viscous liquid with a pH of 7.5.8 Pancreatic drainage is clear and watery with a pH of 8.3.8 Considering that the normal pH of skin is 4.5 to 5.5, the issue of protection of adjacent skin is a primary goal of care.8,9

Goals of Management

The goals of management for a patient with an ECF are complex and require the skills and attention of a collaborative team.11 Early identification of the presence of an impending fistula provides an opportunity to manage complications in a timely fashion.8,13 While an ECF is not a common event, paying attention to certain signs in the patient at risk provides clues to the need for early care. Following abdominal surgery or in cases of inflammatory bowel disease, signs such as fever, localized edema, induration, progressive local discomfort, changes in fluid and electrolyte balance, and altered mental state should be monitored closely and communicated to the physician or surgeon.8,13,14 Once a person is predisposed to develop an ECF, some direct causes include a breakdown of the anastomotic site due to sepsis or tension, peritoneal abscess, altered blood supply, steroid therapy, and malnutrition.15,16

Once an ECF is suspected, it is important to identify the extent and source of the fistula. This can be accomplished through a fistulogram, computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET) scan.8,15 Determining the extent of the ECF provides the information needed to develop a plan of care and guides surgical intervention if needed. Immediate stabilization of the patient by managing his or her electrolytes and fluids is a critical step.8,15,17,18 The drainage from an ECF includes sodium, potassium, magnesium, zinc, proteins, digestive enzymes, and fluid, the loss of which will cause fluid and electrolyte depletion and malnutrition.8,9,11,15,18 The corrosive nature of the effluent will erode the surrounding skin and cause pain.8,9,13,15,16 Supportive efforts are aimed at correcting these problems through intravenous support as well as quantification and containment of effluent.8 It may be necessary to withhold oral intake (NPO) initially until all factors are identified and the extent of the ECF is determined.15,16

Medical Management

The medical management of fistulae has four primary goals: stabilize fluid and electrolyte imbalance, provide nutritional support, manage sepsis, and determine the exact location of the fistula. Supporting these goals provides optimal care for the patient and increases the chance of spontaneous closure of the fistula.15,18 Although spontaneous closure of ECFs occurs in only about a third of cases, this is still the desired outcome. A number of strategies are recommended to achieve these goals. Involving a registered dietitian is critical. Along with the physician, he or she will monitor electrolytes and fluids for replacement needs as well as determine required nutritional support.17,18 Initially, the patient may be NPO while total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is initiated. Resuming feedings through either the oral or enteral route will prevent mucosal villous atrophy in the small bowel and promote optimal nutritional absorption.9,15,17–19 TPN is a viable option if enteral feeding is not possible; however, the risk of hyperglycemia is always present.19–22 Continued monitoring of serum electrolytes and nutritional markers such as prealbumin and transferrin provides important clues to the effectiveness of the nutritional plan of care.19 Pharmacologic treatments are also useful medical management strategies. The use of octreotide or somatostatin has been shown to decrease the volume from a high-output fistula in some cases,8,9,19–21 although the results are not always predictable. Mortality rates increase with sepsis, so the identification and treatment of sepsis in these situations are an important aspect of care23 (Table 19-5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree