Elizabeth Van Den Kerkhof, RN, DrPH

Carolina Jimenez

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Mona Baharestani, PhD, ANP, CWON, CWS, for her work on previous editions of this chapter.

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- describe how wounds and those afflicted by wounds are viewed

- identify the impact of quality of life on patients with wounds and their caregivers

- describe ethical dilemmas confronted in wound care

- identify issues and challenges faced by caregivers of patients with wounds

- describe strategies aimed at meeting the needs of patients with wounds and their caregivers.

Wound healing involves complex biochemical and cellular events. Chronic wounds do not follow a predictable or expected healing pathway, and they may persist for months or years.1 The exact mechanisms that contribute to poor wound healing remain elusive; an intricate interplay of systemic and local factors is likely involved. With an aging population and increased prevalence of chronic diseases, the majority of wounds are becoming recalcitrant to healing, placing a significant burden on the health system and individuals living with wounds and their caregivers. Although complete healing may seem to be the desirable objective for most patients and clinicians, some wounds do not have the potential to heal due to factors such as inadequate vasculature, coexisting medical conditions (terminal disease, end-stage organ failure, and other life-threatening health conditions), and medications that interfere with the healing process.2 Whether healing is achievable or not, holistic wound care should always include measures that promote comfort and dignity, relieve suffering, and improve quality of life (QoL).

Case Study

Margaret is an 86-year-old woman who resides in a long-term care facility. With progressive dementia in the last 5 years, she has become incontinent and experienced significant weight loss due to poor oral intake. Margaret developed a stage IV pressure ulcer (PrU) in the sacral area after a recent hospitalization for exacerbation of heart failure. She continues to exhibit symptoms of dyspnea and prefers to sit in a high Fowler position (head of bed above 45 degrees) in bed to help breathing. She gets agitated when she is repositioned, especially in a side-lying position. Her only daughter is distraught over her mother’s agitation, and she wonders if the constant repositioning is necessary. During a family meeting, the daughter asked the following questions regarding her mother’s care, “If this is not something she likes, are we doing the right thing for her? Is this quality of life?”

Quality of Life and Person-Centered Concerns

What is quality of life (QoL)? Generally, QoL is defined as a general perception of well-being by an individual. It is a subjective but dynamic construct that is influenced by emotions, beliefs and values, social context, and interpersonal relationships, which together account for its variability.3 Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) refers to the sense of well-being that is specifically affected by health and illness along with other related efforts to promote health, manage disease, and prevent recurrence.4 According to the model proposed by Wilson and Cleary,5 multiple overlapping dimensions (e.g., biological and physiological factors, symptoms, functioning, general health perceptions, and overall QoL) are ascribed to the underlying structure of HRQoL. Each component may carry more importance at a given time based on the context of health and illness. Among people with chronic wounds, there is very little dispute that their QoL is severely diminished.6,7

Quality of Life Instruments

There are a number of validated instruments to measure QoL. The generic instruments most commonly used are the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) and adaptations, Research and Development 36-item Form, Sickness Impact Profile, Quality of Life Ladder, Barthel Index, the Nottingham Health Profile, and EuroQol EQ-5D. Specific instruments that are used to evaluate HRQoL for patients with diabetic foot ulcers include Cardiff Wound Impact Schedule Diabetes 39, Norfolk Quality of Life in Diabetes Peripheral Neuropathy Questionnaire, Neuro-QoL, the Manchester-Oxford Foot Questionnaire, and Diabetic Foot Ulcer Scale. For the leg ulcer patient population, the Hyland Leg and Foot Ulcer Questionnaire, Charing Cross Venous Leg Ulcer Questionnaire, and Sheffield Preference-based Venous Leg Ulcer 5D could be considered.8,9

Quality of Life and Chronic Wounds

The three major chronic wound types are PrUs, diabetic foot ulcers, and venous leg ulcers. A PrU is an area of skin breakdown due to prolonged exposure to pressure, shear, and friction leading to tissue ischemia and cell death. PrUs remain a significant problem across the continuum of healthcare services; prevalence estimates range from 3.7% to over 27% depending on the setting of care.10,11 PrUs are linked to a number of adverse patient outcomes including prolonged hospital stay, decline in physical functioning, and death. In fact, patients with a PrU have been reported to have a 3.6-fold increased risk of dying within 21 months, as compared with those without a PrU.12 Gorecki and colleagues12 reviewed and summarized 31 studies (10 qualitative studies and 21 quantitative studies) that examined issues related to QoL in people with PrUs. Common concerns and salient issues were synthesized and categorized into the following themes:

1. Physical restrictions resulting in lifestyle changes and the need for environmental adaptations

2. Social isolation and restricted social life

3. Negative emotions and psychological responses to changes in body image and self-concept, and loss of independence

4. PrU symptoms: management of pain, odor, and wound exudate

5. Health deterioration caused by PrU

6. Burden on others

7. Financial hardship

8. Wound dressings, treatment, and other interventions

9. Interaction with healthcare providers

10. Perception of the cause of PrU

11. Need for education about PrU development, treatment, and prevention

Diabetes is one of the leading chronic diseases worldwide.13 Persons with diabetes have a 25% lifetime risk of developing foot ulcers that precede over 80% of lower extremity amputations in this patient population.14,15 The 5-year mortality rates have been reported to be as high as 55% and 74% for new-onset diabetic foot ulcers and after amputation, respectively; the number of deaths surpasses that associated with prostate cancer, breast cancer, or Hodgkin’s disease.15 Individuals with unhealed diabetic foot ulcers share some unique challenges. Due to problems using the foot and ankle, patients with foot ulcers suffer from poor mobility limiting their ability to participate in physical activities.16 Mobility issues may also interfere with their performance at work resulting in loss of employment and financial hardship. Increased dependence can lead to caregiver stress and unresolved family tension. High levels of anxiety, depression, and psychological maladjustment may affect patients’ abilities to participate in self-management and foot care.16,17

It is estimated that approximately 1.5 to 3.0 per 1,000 adults in North America have active leg ulcers, and the prevalence continues to increase due to an aging population, sedentary lifestyle, and the growing prevalence of obesity.18 Chronic leg ulcers involve an array of pathologies: 60% to 70% of all cases are related to venous disease, 10% due to arterial insufficiency, and 20% to 30% due to a combination of both.19 Although venous leg ulcers are more common in the elderly, 22% of individuals develop their first ulcer by age 40 and 13% before age 30, hindering their ability to work and participate in social activities.20,21 To understand the experience of living with leg ulceration, Briggs et al.22 reviewed findings from 12 qualitative studies. Results were synthesized into five categories, similar to those identified above in individuals with PrUs:

1. Physical effects including pain, odor, itch, leakage, and infection

2. Understanding and learning to provide care for leg ulcers

3. The benefits and disappointment in a patient–professional relationship

4. Social, physical, and financial cost of a leg ulcer

5. Psychological impact and difficult emotions (fear, anger, anxiety)

In two other reviews examining the impact of wounds on QoL, a total of 2223 and 24 studies24 were identified. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included in the reviews. Pain was identified as the most common and disabling symptom leading to problems with mobility, sleep disorders, and loss of employment. Other symptoms associated with leg ulcers, including pruritus, swelling, discharge, and odor, are equally distressing but often overlooked by caregivers. In the studies, patients discussed the impact of leg ulcerations on their ability to work, carry out housework, perform personal hygiene, and participate in social/recreational activities. Patients feel depressed, powerless, being controlled by the ulcer, and ashamed of their body. Efforts were taken to conceal the bandages/dressings with clothing or shoes; however, the latter were often considered less attractive than what would normally be worn. Both reviews identified the need to address patient engagement and patient knowledge deficits to promote treatment adherence.23,24

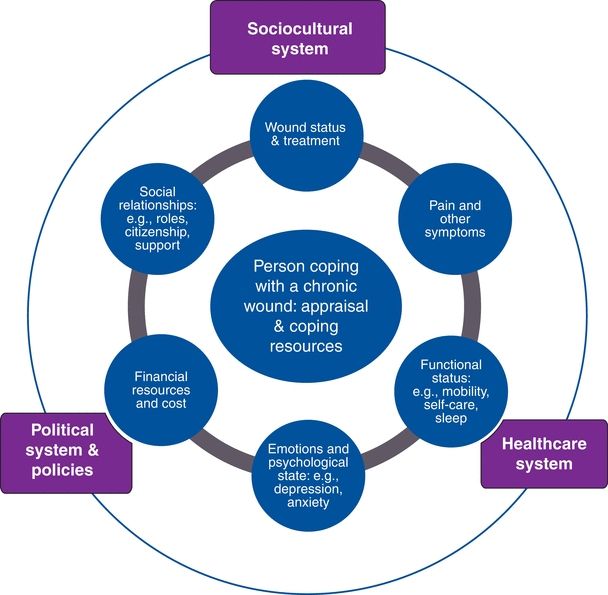

Chronic Wound–Related Quality of Life (CW-QoL) Framework

Based on the above review of the literature, common themes were identified to create a conceptual framework for the concept of QoL as it relates to patients with chronic wounds (Fig. 1-1). Included in the framework are two concentric circles and a center representing the individual coping with a chronic wound. The outer circle represents the social, political, and healthcare systems within which QoL is realized and lived. The inner circle outlines six key stressors encountered by people living with chronic wounds:

Figure 1-1. Chronic wound–related quality of life (CW-QoL) framework. (Copyright © 2014 KY Woo.)

1. Wound status and treatment

2. Pain and other wound-related symptoms

3. Function status and mobility

4. Emotions and psychological state

5. Financial resources and cost

6. Social relationships

To improve patients’ QoL, this paradigm places greater emphasis on the need to foster a climate that elicits patient engagement accompanied by mindful scanning of the environment and health resource mapping. Individualized wound care plans that address specific patient-centered concerns are most likely to succeed and promote the best outcomes for the patient with a wound. Standardized wound care plans often fail because they do not promote patient adherence/coherence. Patients may be labeled “noncompliant” when the real problem is that the care plan has not been properly individualized to their specific needs taking into account their perspectives on QoL.

Person Coping with a Chronic Wound

People who are living with chronic wounds describe the experience as isolating, debilitating, depressing, and worrisome, all of which contribute to high levels of stress. Stress has a direct impact on QoL. Lazarus and Folkman25 postulated that stress is derived from cognitive appraisals of whether a situation is perceived as a threat to one’s well-being and whether coping resources that can be marshaled are sufficient to mitigate the stressor. Stress appraisal is constructed when the demands of a situation outstrip perceived coping resources.25 While no one is immune to stress, the impact of a chronic wound on individual’s perception of well-being and QoL depends on personal meanings and values that are assigned to the demands that arise from living with a chronic wound. Coping is less adaptive or effective if people lack self-esteem, motivation, and the conviction that they have the aptitude to solve a problem. Woo26 evaluated the relationship between self-perception and emotional reaction to stress in a sample of chronic wound patients. Findings suggest that people who are insecure about themselves tend to anticipate more wound-related pain and anxiety.

Chronic Stress Is Not Innocuous

Stress triggers a cascade of physiological responses featured by the activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis that produces vasopressin and glucocorticoid (cortisol).27 Vasopressin is known for its property to induce vasoconstriction that could potentially be harmful to normal wound healing by compromising the delivery of oxygen and nutrients. Cortisol attenuates the immunoinflammatory response to stress. Excessive cortisol has been demonstrated to suppress cellular differentiation and proliferation, inhibit the regeneration of endothelial cells, and delay collagen synthesis. The body of scientific evidence that substantiates the deleterious impact of protracted stress on wound healing is convincing.28 In one study, Ebrecht et al.29 evaluated healing of acute wounds created by dermal biopsy among 24 healthy volunteers. Stress levels reported by the participants via the Perceived Stress Scale were negatively correlated to wound healing rates 7 days after the biopsy (P < 0.05). Subjects exhibiting slow healing (below median healing rate) rated higher levels of stress during the study (P < 0.05) and presented higher cortisol levels 1 day after biopsy than did the fast-healing group (P < 0.01). Kiecolt-Glaser and colleagues30 compared wound healing in 13 older women (mean age = 62.3 years) who were stressed from providing care for their relatives with Alzheimer disease, and 13 controls matched for age (mean age = 60.4 years). Time to achieve complete wound closure was increased by 24% or 9 days longer in the stressed caregiver versus control groups (P < 0.05).

Cognitive–behavioral strategies and similar psychosocial interventions are designed to help people reformulate their stress appraisal and regain a sense of control over their life’s problem within an empathic and trusting milieu. Ismail et al.31,32 identified 25 trials that utilized various psychological interventions (e.g., problem solving, contract setting, goal setting, self-monitoring of behaviors) to improve diabetic self-management. Patients allocated to psychological therapies demonstrated improvement in hemoglobin A1c (12 trials, standardized effect size = −0.32; −0.57 to −0.07) and reduction of psychological distress including depression and anxiety (5 trials, standardized effect size = −0.5; −0.95 to −0.20).

Simple problem-solving technique is easy to execute and provides a step-by-step and logical approach to help patients identify their primary problem, generate solutions, and develop feasible solutions. The key sequential steps are31:

1. explanation of the treatment and its rationale

2. clarification and definition of the problems

3. choice of achievable goals

4. generation of alternative solutions

5. selection of a preferred solution

6. clarification of the necessary steps to implement the solution

7. evaluation of progress.

Wound Status and Management

The trajectory for wound healing is tortuous and unpredictable punctuated by wound deterioration, recurrence, and other complications. Despite appropriate management and exact adherence to instructions, there is no guarantee that healing will occur. The following quotes are some of the narratives that patients voiced to convey their worry, frustration, and feeling of powerlessness.

“The wound doctor asked me to use this dressing, but the wound is not getting better. I don’t know what else to do?”33

“The wound is getting bigger, and now I am getting an infection; I don’t know why this is happening to me?”33

Even when best practice is implemented, some treatment options are not feasible and they are not conducive to enhance patients’ QoL, for example, a patient with foot ulcers who cannot use a total contact cast because he needs to wear protective footwear at work and he cannot maintain his balance walking on a cast; a patient with venous leg ulcer who likes to take a shower every day to maintain personal hygiene but cannot do so because she needs to wear compression bandages; or a patient with a PrU who refused an air mattress because it generates too much noise that interferes with sleep. While turning patients every 4 hours has been recommended, repositioning can be painful, especially among patients who have significant contractures, increased muscle spasticity, and spasms. Among critically ill individuals, repositioning may precipitate vascular collapse or exacerbate shortness of breath (as with, e.g., advanced heart failure).34 According to the study of hospitalized patients with PrUs,35 it was surprising for investigators to learn that even assuming a side-lying position could be uncomfortable. Briggs and Closs36 indicated that only 56% of patients in their study were able to tolerate full compression bandaging, with pain being the most common reason for nonadherence. Patients should be informed of various treatment options and be empowered to be active participants in care. Being an active participant involves taking part in the decision making for the most appropriate treatment, monitoring response to treatment, and communicating concerns to healthcare providers.

Much discussion in the qualitative literature has been centered on patients trying to find explanations on how chronic wounds develop.22,23 As a reminder, only a small proportion of patients are cognizant of factors contributing to their chronic wounds and treatment strategies to improve their conditions.37 Patients and family need to understand that chronic wounds are largely preventable but not always avoidable. When circulation is diverted from the skin to maintain hemodynamic stability and normal functioning of vital organs, skin damage is inevitable.

Complications such as wound infection are common but upsetting. According to an analysis of an extensive database comprising approximately 185,000 patients attending family medical practitioners in Wales, 60% of patients with chronic wounds had received at least one antibiotic in a 6-month period for the treatment of wound infection.38 Bacteria compete for nutrients and oxygen that are essential for wound healing activities, and they stimulate the overproduction of proteases leading to degradation of extracellular matrix and growth factors.39 Among patients with diabetic foot ulcers, wound infection is one of the major risk factors that precede amputations. Surgical site infection has been linked to prolonged hospitalization and high mortality.40 In fact, the mortality rate has been reported to be over 50% in patients with bacteremia secondary to uncontrolled infection in PrUs.38 Receiving a diagnosis of an infection is anxiety provoking; patients often fear that infection is the beginning of a downward vicious cycle leading to hospitalization, limb amputation, and death. The need to align expectations and dispel misconceptions cannot be underestimated.

Pain and Other Symptoms

Wound-associated pain continues to be a common yet devastating symptom, often described as one of the worst aspects of living with chronic wounds.41 Sleep disturbance, immobility, poor appetite, and depression are some of the consequences of unremitting pain. In an international survey of 2018 people with chronic wounds, over 60% of the respondents reported the experience of pain “quite often” and “all the time.”42 Szor and Bourguignon43 reported that as many as 88% of people with PrUs in their study expressed PrU pain at dressing change and 84% experienced pain even when unprovoked. Of people with venous leg ulcers, the majority experienced moderate to severe levels of pain described as aching, stabbing, sharp, tender, and tiring.44 Pain has been documented to persist up to at least 3 months after wound closure. Contrary to the commonly held belief that most patients with diabetic foot ulcers do not experience pain due to neuropathy, up to 50% of patients experience painful symptoms at rest and approximately 40% experience moderate to extreme pain climbing stairs or walking on uneven surfaces.45 Patients with diabetes who report pain most or all of the time had statistically and clinically significantly poorer health-related QoL than those who did not report pain.46 However, pain in diabetes is often underestimated and undertreated. The need to improve pain assessment and management is incontestable. Pharmacotherapy continues to be the mainstay for pain management. Appropriate agents are selected based on severity and specific types of pain (see Chapter 12, Pain Management and Wounds).

Pruritus

Pruritus is another frequent complaint among people with chronic wounds. Of 199 people with chronic wounds who were surveyed, Paul, Pieper, and Templin47 documented that 28.1% complained of itch. Peripheral pruritus is often triggered by pruritogens (e.g., histamine, serotonin, cytokines, and opioids), giving rise to signals that are transmitted via pain-related neuronal pathways and terminated in somatosensory cortex where the sensation of itch is perceived.48 In contrast, central pruritus is associated with psychiatric disorders or damages to the nervous system mediated through opioid and serotonin receptors. For patients with wounds, itch is commonly caused by peripheral stimulation of itch receptors due to irritation of the skin and related dermatitis.49 People with chronic wounds are exposed to a plethora of potential contact irritants accounting for approximately 80% of all cases of contact dermatitis. Excessive washing and bathing strips away surface lipid and induces dryness that can exacerbate pruritus. To replenish skin moisture, humectants or lubricants should be used on a regular basis. Drug treatment with paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, and gabapentin has been shown to be beneficial in palliative care patients.

Odor

Probst interviewed people with fungating breast wounds, and odor was highlighted as one of the most distressing symptoms that compromised their QoL.50 Unpleasant odor and putrid discharge is associated with increased bacterial burden, particularly involving anaerobic and certain gram-negative (e.g., pseudomonas) organisms. Metabolic by-products that produce this odor include volatile fatty acids (propionic, butyric, valeric, isobutyric, and isovaleric acids), volatile sulfur compounds, putrescine, and cadaverine.48 To eradicate wound odor, topical antimicrobial and antiseptic agents are recommended.

Exudate

Wound exudate contains endogenous protein-degrading enzymes, known as proteases or proteinases that are extremely corrosive and damaging to the intact skin.51 When drainage volume exceeds the fluid handling capacity of a dressing, enzyme-rich and caustic exudate may spill over the wound margins, causing maceration or tissue erosion (loss of part of the epidermis but maintaining an epidermal base) and pain. Leakage of highly exudative wounds on to clothing, furniture, and bed linens can lead to feelings of embarrassment and inhibited sexuality and intimacy.52–54 Careful selection of discreet absorbent dressings (avoid bulky materials) will improve patients’ QoL.

Functional Status

According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health of the World Health Organization, disability refers to impairment, activity limitations, and participation restrictions because of the interaction between a health condition and other physical, social, mental, or emotional factors.55 The majority of patients with chronic wounds suffer mobility problems, and their ability to perform activities of daily living is limited. Activities often taken for granted by the general population, such as taking a shower, getting dressed, and even walking up the stairs, could become an enormous challenge for people with chronic wounds. In a study consisting of 88 patients with chronic leg ulcers, 75% reported difficulty performing basic housework.56 Yet another study by Hyland et al.57 revealed that of 50 patients with leg ulcers, 50% had problems getting on and off a bus and 30% had trouble climbing steps. Due to increased disability, patients are becoming ever more dependent on others for help. Requesting and receiving assistance could be a hassle and embarrassment, especially if the patient lives alone and needs regular help. Easy access to transportation and changes to living arrangements (such as widening doors for a wheelchair) will enhance individual’s ability to functional independently, but the effort to organize and execute the plan could be daunting.34

Emotional and Psychological State

People with chronic wounds tend to experience more emotional problems than people without wounds in the community and are less capable to cope with stressful events.58 Healthcare practitioners (n = 908), in responding to a Web-based survey, acknowledged that mental health issues are common in people with chronic wounds. Over 60% of the survey respondents indicated that between 25% and 50% of people with chronic wounds suffer from mental disorders.59 Among all the symptoms, anxiety was rated the most common (81.5%). These results are consistent with findings from a pilot study in which over 60% of people living with chronic wounds expressed higher-than-average anxiety.60

Financial and Cost

Patients with chronic wounds are often unemployed, marginalized, and isolated. In a study of 21 patients with diabetic foot ulcers by Ashford, McGee, and Kinmond,61 79% of patients reported an inability to maintain employment secondary to decreased mobility and fear of someone inadvertently treading on their affected foot. In another study, all patients interviewed felt that the leg ulcer limited their work capacity, with 50% adding that their jobs required standing most of their shift.62 In that same study, 42% of patients identified the leg ulcer as a key factor in their decision to stop working. Even for younger patients, leg ulceration was correlated with time lost from work and job loss, ultimately affecting finances.62 Beyond occupational stressors and dilemmas, patients may incur additional out-of-pocket expenses for transportation, parking, telephone bills for medical follow-up, home health aide services, dressing supplies not covered by insurance, and drug costs if they have no prescription plan. Those who have no insurance but don’t qualify for public assistance may be forced to tap into their savings or refinance their homes. Healthcare professionals, rather than simply dismissing patients as nonadherent, should show empathy, acknowledging access and financial hardships faced by patients, and partner with their patients in addressing these issues.63,64

Social Relationships and Role Function

Feeling embarrassed about the repugnant smell and fluid leakage from wounds and their bodies, people with chronic wounds may intentionally avoid social contacts and activities. Patients often feel detached and emotionally distant from their friends and families, rendering it difficult to maintain meaningful friendship and romantic relationships. Patients with chronic wounds are frequently isolated and lack social support. The concept of social support refers to an interactive process that entails perceived availability of help or support actually received. In a study of 67 patients with venous leg ulcers, Edwards and coinvestigators65 evaluated the impact of a community model of care on QoL. Subjects were randomized to receive individual home visits from community nurses (the control group) or to pay a weekly visit to a nurse-managed leg club (the intervention group). Leg clubs offer a setting where the subjects could obtain advice/information to manage their ulcers through social interaction with expert nurses as well as with their peers. Subjects who attended the leg club expressed significant improvement in QoL (P < 0.014), morale (P < 0.001), self-esteem (P = 0.006), pain (P = 0.003), and functional ability (P = 0.004).

The notion that social media could be leveraged to provide virtual social support is gaining popularity. Social media encompasses a variety of platforms that provide opportunities for multiple users to exchange experiences and information and to provide support through multisensory communication. According to a 2012 survey, 61% of adult Internet users searched online and 39% used social media to obtain health information.66 Of all the posted messages and dialogues that were abstracted from 15 Facebook groups focused on diabetes management, almost 30% of the content was related to the exchange of emotional support among members of a virtual community.67 In one study that evaluated an online diabetes self-management program,68 individuals randomized to the program exhibited a significant improvement in blood sugar control (A1c level), self-reported knowledge/skill, and self-efficacy compared with those who received usual care. However, the actual participation in household activities, recreation, and exercise was not different between the two study groups. Nicholas et al.69 designed an online module to educate and provide support to adolescents with diabetes. Participants who were randomized to the treatment group received eight online information modules and participated in peer-to-peer online dialogue that was moderated by a social worker specialized in diabetes care. Perceived social support was rated higher in the treatment group compared to the control group, but the result was not significant given the small sample size (n = 31).

Healthcare System

Navigating through the healthcare system could be extremely confusing. A trusting and therapeutic relationship between patients and their healthcare providers may serve to buffer the effects of adversity and stress. However, patients sometimes criticize about feeling rushed and spending limited time during routine visits at wound care clinic. Patients discussed the importance of having healthcare providers who care and display a genuine interest in their well-being. In their description of the key attributes of someone who cares, patients use terms like “caring,” “holistic,” “friendly,” being “vigilant,” “cheerful,” “gentle,” and “knowledgeable.” Healthcare providers should provide clear and consistent communication, to avoid confusion.

Sociocultural System

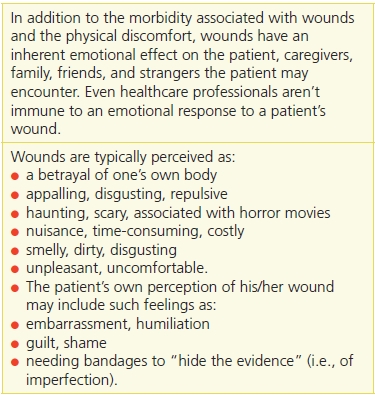

A recurring theme emerged from the literature that articulated the bleak feeling of isolation due to wound-related stigma. Given the negative image by which wounds are viewed (Table 1-1), it isn’t surprising that patients with wounds are sometimes considered unattractive, imperfect, vulnerable, a nuisance to others, and, in some cases, even repulsive.70–72 This can dramatically affect a patient’s emotional response to their wound and their self-esteem. For patients who must endure the displeasing stares of others to their bandaged wounds, a wound clinic may be the only place where they can receive positive energy and reinforcement.37

Table 1-1 Emotional Impact of Wounds

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree