Elizabeth A. Ayello, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CWON, MAPWCA, FAAN

Jeffrey M. Levine, MD, AGSF, CMD, CWS

Kimberly LeBlanc, MN, RN, CETN(C)

Marjana Tomic-Canic, PhD, RN

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- discuss the functions and different layers of the skin

- identify the components of a skin assessment

- list skin changes associated with the aging process

- differentiate between skin assessment and wound assessment

- identify and classify common skin conditions

- explain moisture-associated skin damage (MASD)

- describe ISTAP classification system for skin tears

- indicate prevention and treatment care options for skin tears

- define the concepts of skin failure and skin changes at the end of life.

Skin Anatomy and Physiology

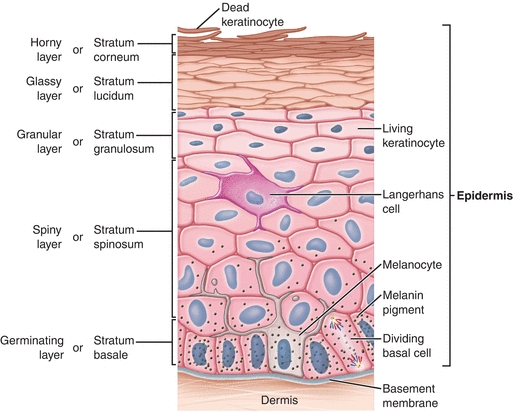

The skin is the largest external organ of the body. Human skin is composed of two distinct layers: the epidermis, the outermost layer; and the dermis, the innermost layer (Fig. 4-1). The dermal–epidermal junction, commonly referred to as the basement membrane zone (BMZ), separates the two layers. Under the dermis lies a layer of loose connective tissue, called subcutaneous tissue, or hypodermis (Table 4-1).

Figure 4-1. Layers of the skin. Two distinct layers of skin, the epidermis and dermis, lie above a layer of subcutaneous fatty tissue (also called the hypodermis). The dermal–epidermal junction (also called the basement membrane zone) lies between the dermis and epidermis.

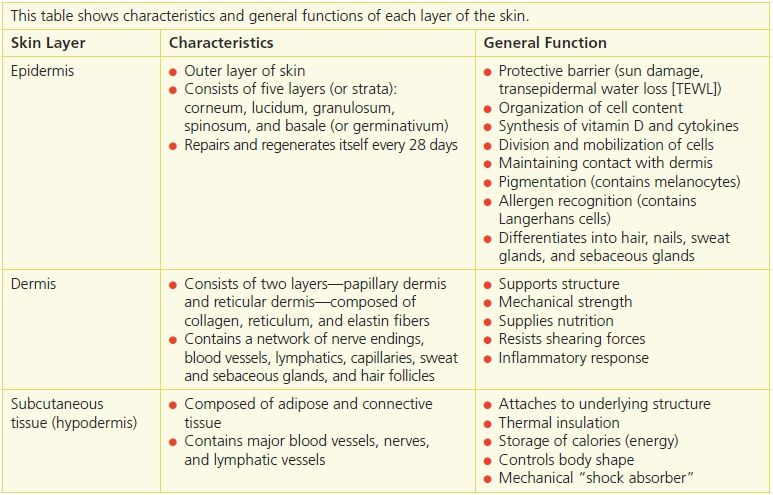

Table 4-1 Skin Layer Functions

The epidermis is a thin, avascular layer that regenerates itself every 4 to 6 weeks. It’s divided into four layers or strata (presented in order from the outermost layer inward).

- Stratum corneum (horny layer)—consists of dead keratinocyte cells; flakes and sheds; is easily removed during bathing activities and more efficiently by scrubbing the surface of the skin.

- Stratum granulosum (granular layer)—also contains Langerhans cells in addition to keratinocytes.1

- Stratum spinosum (spiny layer)—contains keratinocytes and Langerhans cells.

- Stratum basale (germinating layer)—single layer of epidermal cells (keratinocytes); contains melanocytes; can regenerate.

A fifth layer, the stratum lucidum (glassy layer), lies between the stratum corneum and the stratum granulosum. This packed translucent line of cells is found only on the palms and soles and not seen in thin skin.

The epidermis is composed of keratinocyte cells. Basal keratinocytes (stratum basale) have the capacity to divide, giving rise to suprabasal layers of epidermis. Once basal keratinocytes leave the stratum basale, they start the process of differentiation, during which they die. This process involves making insoluble proteins and their crosslink which, along with lipids and membrane components, form the insoluble, horny stratum corneum layer.2–5,5 In order to maintain the barrier, keratinocytes have the capacity to completely regenerate the epidermis. If damaged (such as wounded, burned, exposed to ultraviolet [UV] light or chemicals), keratinocytes, in order to repair the damage, change their biology. Instead of differentiating, they become “activated” and start to divide rapidly and, in the case of a wound, they migrate over the gap to repair the damage.3 They also signal to other neighboring cell types, such as fibroblasts, Langerhans cells, and melanocytes, that the skin barrier is compromised and that they’re needed to help repair the damage. Once the damage is repaired, the keratinocytes cease their activation and resume their normal differentiation process.6

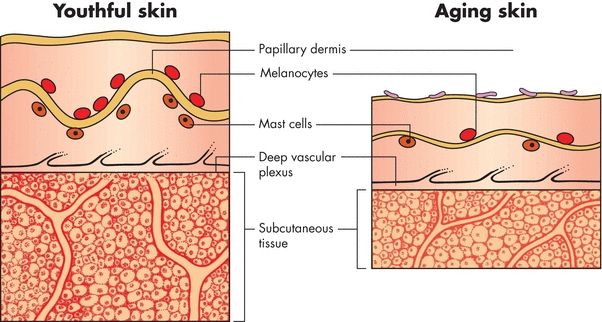

The BMZ divides the epidermis from the dermis. It contains fibronectin (an adhesive glycoprotein), type IV collagen (a non–fiber-forming collagen), heparin sulfate proteoglycan, and glycosaminoglycan.7 The BMZ has an irregular surface—called rete ridges or pegs—projecting downward from the epidermis that interlocks with the upward projections of the dermis. The two interlocking sides resemble the two sides of a waffle iron coming together. This structure anchors the epidermis to the dermis, preventing it from sliding back and forth. As skin ages, the basement membrane flattens, and the area of contact between the epidermis and dermis is decreased by 50%, thus increasing the risk of skin injury by traumatic, accidental separation of the epidermis from the dermis (Fig. 4-2).

Figure 4-2. Effects of aging on the basement membrane zone (BMZ). The illustrations below show the effects of aging on the BMZ. Specifically, the basement membrane flattens, reducing the area of contact between the epidermis and the dermis by 50%.

The dermis is an essential part of the skin and is commonly referred to as the “true skin.”8 As the second layer, it’s the thickest layer and is composed of many cells. The major proteins found in this layer are collagen and elastin, which are synthesized and secreted by fibroblasts; collagen forms up to 30% of the volume or 70% of the dry weight of the dermis.7–9 The dermis is a matrix that serves to support the epidermis. It’s divided into two areas, the papillary dermis and the reticular dermis.7

- The papillary dermis is composed of collagen and reticular fibers. Its distinct, unique pattern allows fingerprint identification for each individual. It contains capillaries for skin nourishment and pain touch receptors (pacinian corpuscles and Meissner’s corpuscles).

- The reticular dermis is composed of collagen bundles that anchor the skin to the subcutaneous tissue. Sweat glands, hair follicles, nerves, and blood vessels can be found in this layer.

The main function of the dermis is to provide tensile strength, support, moisture retention, and blood and oxygen to the skin.8 It protects the underlying muscles, bones, and organs. The dermis also contains the sebaceous glands that secrete sebum, a substance rich in oil that lubricates the skin. Furthermore, it also contains hair follicles that are the source of multipotent stem cells, which have the capacity to restore the epidermis.6

The subcutaneous tissue, or hypodermis, attaches the dermis to underlying structures. Its function is to promote an ongoing blood supply (blood reservoir) to the dermis for regeneration. It’s primarily composed of adipose tissue, which provides a cushion between skin layers, muscles, and bones. It promotes skin mobility, molds body contours, and insulates the body.

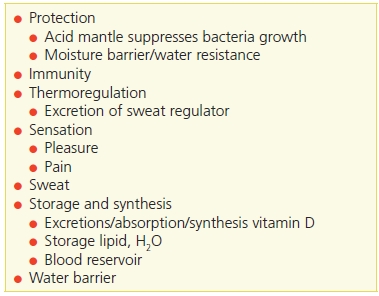

Skin Roles and Functions

Skin is an important organ whose diverse functions are not always appreciated (Table 4-2). In adults, the skin weighs between 6 and 8 pounds (2.7 to 3.6 kg) and covers over 20 ft2 (1.9 m2). Skin thickness varies from 0.5 to 6 mm according to its location on the body; for example, skin can be as thin as  on the eyelids and as thick as

on the eyelids and as thick as  on the palms and soles, where greater protection is needed. The skin receives one-third of the body’s circulating blood volume—an oversupply of blood compared to its metabolic needs.

on the palms and soles, where greater protection is needed. The skin receives one-third of the body’s circulating blood volume—an oversupply of blood compared to its metabolic needs.

Table 4-2 Skin Roles and Functions

Ayello, E.A., Sibbald, R.G., Quiambao, P.C.H.., et al. “Introducing a Moisture-Associated Skin Assessment Photo Guide for Brown Pigmented Skin,” World Council of Enterostomal Therapists Journal 34(2):18–25, 2014.

The normal range of skin pH is 4 to 6.5 in healthy people.10,11 This “acid mantle” helps to maintain a normal skin flora by serving as a protective barrier against bacterial and fungal infections. It also supports the formation and maturation of epidermal lipids and assists in maintaining their protective barrier function. The acid mantle also provides indirect protection against invasion by microorganisms and protection against alkaline substances.10 If the acid mantle loses its acidity, the skin becomes more prone to damage and infection. Frequent use of soap products and overwashing can alter the stratum corneum and its ability to serve as a protective barrier. Alternatively, several skin conditions can increase the skin’s surface pH, including eczema, contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and dry skin.12,13 Systemic diseases may also increase the skin’s surface pH, such as in diabetes, chronic renal failure, and cerebrovascular disease.14

The skin’s major functions are protection, immunity thermoregulation, sensation, sweat, storage and synthesis, and water barrier.15,16 Skin protects the body by serving as a barrier from invasion by organisms such as bacteria. Epidermis synthesizes natural antimicrobials called defensins.17 Because staphylococcal species (such as Staphylococcus aureus or Staphylococcus epidermis) tolerate salt, they are present in large numbers as resident bacteria on the skin.15,17 Another organism found on the skin is yeast, which is commonly found on the trunk and ears and as fungus between the toes.15,18 In addition, skin makes its own antimicrobial peptides called defensins.19,20

Sensation is a key function of the skin. Areas that are most sensitive to touch have a greater number of nerve endings.18 These include the lips, nipples, and fingertips. In humans, the fingertips are the most sensitive touch organ and enable us to correctly identify objects by touch (stereognosis) rather than by sight. Many tactile corpuscles lie at the base of hair follicles, and shaving reduces the tactile sensibility of that skin area. In hairless body regions, the tactile corpuscles are called Meissner’s corpuscles.18 Pleasurable, firm touching sensations, such as from a massage or hugs of affection, are transmitted via the skin as they generate nerve transmissions through these tactile corpuscles.

Itch is one of the alarm sensations of the skin and serves as a defense mechanism. Chemicals that are released after skin injury may promote the inflammatory process and can also induce itch or pain. Itch and pain are in close regulatory relationship—for example, central pain inhibition may enhance the act of itching, while also inhibiting the act of itching.21

Somatic pain (from the outer body surfaces and framework) is also communicated through the skin. Superficial (acute) pain to a local area is usually transmitted by very rapid nerve impulses by A-delta fibers18 and tends to be sharp but ceases when the pain stimulus stops. Deep (chronic) pain impulses are transmitted slowly over the smaller, thinly myelinated C fibers. In contrast, this type of pain tends to spread over a more diffuse area, lasts for longer periods of time, and remains even after the pain stimulus is gone.18 As a sign of possible skin injury, pressure also serves as a protective warning sensation.

Temperature regulation and fluid and electrolyte balance are achieved in part by the skin. Thermoregulation is controlled by the hypothalamus in response to internal core body temperature. Peripheral temperature receptors in the skin assist in this process called temperature homeostasis.22 By losing a copious amount of water—for example, sweating—through the skin, lungs, and buccal mucosa, homeostasis of body temperature is maintained. Skin temperature is controlled by the dilatation or constriction of skin blood vessels. When body core temperature rises, the body will attempt to reduce its temperature by releasing heat from the skin. This is accomplished by sending a chemical signal to increase blood flow in the skin from vasodilation, thus increasing skin temperature.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Increased temperature → Skin blood vessel vasodilation → Heat loss from epidermis → Body maintains temperature homeostasis.

In contrast, the opposite occurs when the body’s core temperature is reduced; the chemical signal causes decreased blood flow from vasoconstriction, thus lowering the skin’s temperature.22,23

Practice Point

Practice Point

Decreased temperature → Skin blood vessel vasoconstriction → Heat conservation → Body maintains temperature homeostasis.

The skin also aids in the excretion of end products of cell metabolism and prevents excessive loss of fluid. Other important functions of the skin include its manufacturing ability and immune functions.24 For example, when exposed to UV light, the skin can synthesize vitamin D.25 Although the skin’s hypersensitivity responses in allergic reactions are commonly seen, the skin’s role in immune function isn’t always fully appreciated. Indeed, Langerhans cells and tissue macrophages, which play an important role in digesting bacteria, as well as mast cells, which are needed to provide proper immune system functioning, are all present in the skin.1,7,15 In addition, keratinocytes are very powerful in generating rapid inflammatory response because they contain prestored proinflammatory signals, such as interleukin-1, which gets released the moment the barrier is broken and is considered the first signal of wounding.26

Aging and the Skin

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Causes of Aging Skin

Changes that occur to human skin as it ages are classified as intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic refers to physiologic changes taking place in the aging process and are most evident in sun-protected areas, while extrinsic refers to environmental influences. It is sometimes difficult to separate intrinsic from extrinsic factors due to the pervasive impact of diet and lifestyle factors, but there are profound genetic and ethnic differences in the body’s response to both.

One major factor impacting both intrinsic and extrinsic aging is oxidative stress leading to macromolecular damage and cell senescence. Changes of aging depend largely upon homeostasis between free radical production and the proper working of repair systems. The term reactive oxygen species (ROS) refers to free radical and nonradicals that contain an oxygen atom. ROS are by-products of cell respiration that takes place in mitochondria during oxidative phosphorylation but are generated by other cellular structures such as peroxisomes and endoplasmic reticulum.27 Not only does ROS increase with age but aging is accompanied by reduced antioxidant activity and decreased DNA repair capability.

Extrinsic causes of aging skin are also mediated by oxidative stress and ROS. The most important cause of aging skin is UV light from the sun, which is divided into UVA and UVB. UVA is considered more damaging because of its deeper penetration into the dermis. Other environmental factors recognized as extrinsic causes of aging include cigarette smoke, ozone, and airborne particulate matter with adsorbed polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.28 These extrinsic factors generate free radicals and ROS that overwhelm the body’s natural antioxidant defenses and stimulate lipid peroxidation reaction cascade which in turn releases proinflammatory mediators that include matrix metalloproteases (MMPs). Mitochondrial DNA mutations resulting from ROS leads to defective electron transfer activity and oxidative phosphorylation.

Telomere shortening is a known result of oxidative insults resulting from environmental factors but is also associated with psychological stress.29 Telomeres are repetitive DNA sequences at the end of linear DNA that shorten each time a cell divides and ultimately leads to cessation of cell division and apoptosis, or programmed cell death.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons adsorbed to airborne particulate matter induce xenobiotic metabolism that releases ROS and MMPs that accelerate aging. Xenobiotic metabolism refers to the metabolic pathways the body uses to eliminate environmental toxins such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons that are adsorbed to airborne particulate matter.

Changes in Aging Skin

Age-related changes in the dermis are numerous, and their cumulative effect increases susceptibility to environment and internal stresses that lead to increased fragility and impaired wound healing. The most striking is the approximately 20% loss in dermal thickness that accounts for the paper-thin appearance of aging skin.30,31 This decrease in dermal cells and proportional reduction in collagen fibers, blood vessels, nerve endings, and collagen lead to altered or reduced sensation, thermoregulation, rigidity, moisture retention, and sagging skin.30,32

A decrease in differentiation and formation of the stratum corneum is also detected in aging skin. In the epidermis, there is reduced keratinocyte proliferation and turnover time, and surface pH is less acidic. Desquamation is less effective, and lipid biosynthesis in the stratum corneum is impaired. There are decreased melanocytes that protect from UV radiation and decreased Langerhans cells that process microbial antigens and present them to other immune system cells. This is accompanied by altered T- and B-cell function, and a general proinflammatory environment that is now an accepted component of the aging process.

The dermal–epidermal junction is flattened with smoothing of the rete ridges and decreased adhesion of this critical mechanical defense barrier. The dermis becomes atrophic with reduced numbers of fibroblasts and mast cells, and collagen becomes disorganized with change in synthesis from type I to type III. There is decreased synthesis of elastin, and elastic tissue is degraded with overall loss of elasticity.

Reduced collagen deposition in elderly skin could explain the development of dermal atrophy and might relate to poor wound healing.33 The subcutaneous fat below the dermis consists primarily of adipose tissue and provides mechanical protection and insulation. Its loss during aging results in parallel reductions in these protective functions. Subcutaneous tissue undergoes site-specific atrophy in such areas as the face, dorsal aspect of the hands, shins, and plantar aspects of the foot, increasing the energy absorbed by the skin when trauma occurs to these areas.33

Many of the changes in aged skin are linked to the hormones estrogen and androgen. Decreased estrogen in menopausal women, similar to ovariectomized mice, leads to a decrease in collagen deposition, slower epithelialization, and delayed wound healing. These effects may be reversible by hormone replacement therapy (HRT).34 In addition, a genetic polymorphism in estrogen receptor-beta has been linked to a predisposition to venous ulcerations in both male and female patients.34 In contrast to estrogen, which is beneficial for wound healing, androgens are implicated in the etiology of venous ulcerations.35 In addition, use of inhibitor (antagonist of androgen) or castration in mice leads to increased collagen deposition and acceleration of wound healing.36

Decreased mechanoreceptors including Meissner’s and Pacini’s corpuscles result in diminished sensation to light touch, pressure, and vibration. A decrease in pain perception may make elderly people more vulnerable to traumatic environmental insults such as wearing tight shoes, stepping on an object, or hitting legs on the side of a chair. Aging skin is also less able to manufacture vitamin D when exposed to sunlight.30,31 The number of Langerhans cells and mast cells diminishes in aging skin, translating into decreased immune function.30–37 Medications also have adverse effects on the skin’s immune function. For example, steroids cause thinning of the epidermis.31,38

There are decreased pilosebaceous units that are composed of hairs, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles, which contribute to decreased sebum production. Impaired thermoregulation results from loss of subcutaneous fat results in decreased energy stores and along with decreased autonomic nerves from the sympathetic nervous system and decreased dermal vascularity. Loss of sweat glands also contributes to impaired thermoregulation as well as decreased ability to manage water balance in response to antidiuretic hormone.

Skin changes seen with aging are accelerated by sun exposure, specifically due to UV radiation.30,39 UV irradiation causes local inflammation and local immunosuppression with DNA damage. Changes induced by photoaging are superficially similar but differ slightly under the microscope. Photo-damaged skin looks coarse, rough, and wrinkled and is prone to developing malignancy.

Aging skin is less able to retain moisture due to a decrease in dermal proteins, which leads to oncotic pressure shifts and diminished fluid homeostasis, thereby putting elderly people at risk for dehydration. Normal water content of the skin is 10% to 15%. Below 10%, the skin becomes dry and is more vulnerable to damage.31 Because soap increases the skin’s pH to an alkaline level, using emollient soap and bathing every other day, instead of every day, can decrease the incidence of skin injury, such as skin tears, in elderly patients.10

An elderly person’s skin is less stretchable due to a decrease in elastin fibers.30,33,37 Because of the thinning of the epidermal layer, the skin becomes a less-effective barrier against water loss, bruising, and infection, accompanied by impaired thermal regulation, decreased tactile sensitivity, and decreased pain perception.30,31,40,41 Due to a decreased amount of dermal proteins, the blood vessels become thinner and more fragile, thereby leading to a type of hemorrhaging known as senile purpura. Hematomas can dissect into surrounding skin, usually over the extensor surfaces of the hands and forearms, resolving to leave brownish discoloration caused by hemosiderin deposits. The appearance of dissecting hematomas can mimic dermal changes associated with bleeding diathesis or impaired clotting system.

Skin Assessment

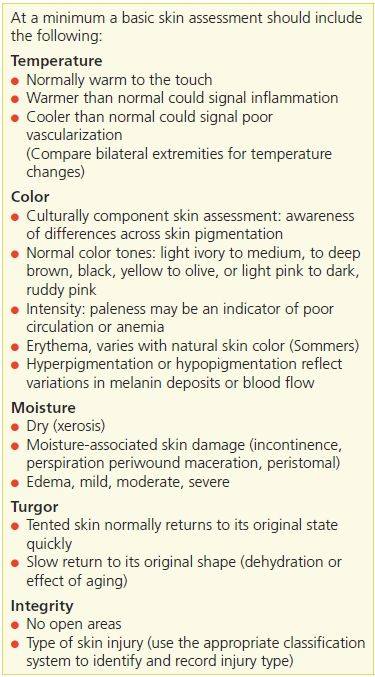

A skin assessment begins with a head to toe inspection and palpation of the skin.42,43 A minimal basic skin assessment should include the following five parameters: temperature, color, moisture, turgor, and intact skin or presence of open areas. Looking and touching the skin is part of a patient assessment. Lacking consensus in the literature as to what constitutes a minimal skin assessment, the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recommends to long-term care (LTC) facilities these five parameters for skin assessment (Table 4-3).

Table 4-3 Elements of a Basic Skin Assessment

A review of the patients’ history should capture the usual skin care practices including bathing routine (shower, or bath) and type of skin/soap products used or preferred. A family history of any skin conditions should be elicited, as well as any known skin allergies.

Skin Temperature

Skin temperature should be assessed by comparing bilateral extremities for coolness or warmth. Warmth can be an indication of inflammation, or chronic venous insufficiency while coolness could signal diminished vascular supply.

Skin Color

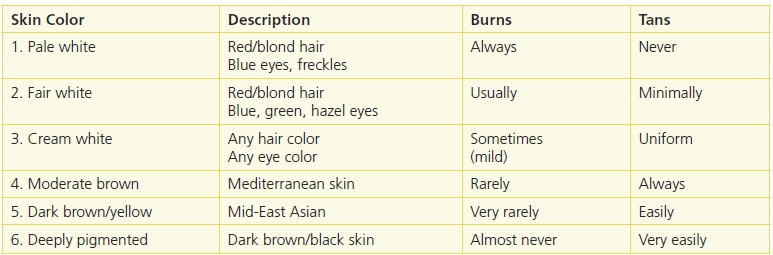

Skin color can reflect various skin conditions. Assessing for changes in a person’s normal skin tones is extremely challenging. In order to evaluate skin color, one needs adequate light (natural light or halogen is preferred) to see if there are any changes in the skin tone. Healthcare professionals are caring for many diverse populations with varying skin colors/tones.16 Clinicians need to keep this in mind, when assessing the nuances of changes in patients’ skin.16,43,44 Differences in skin color pigmentation can be described using Fitzpatrick’s skin categories.45 The four categories were expanded to include East Asian and Black skin types. Each of the six categories include the skin’s response to UV radiation16 (Table 4-4).

Table 4-4 Variation of Skin Colors

“The first three skin types are most likely to have chronic sun damage. Lighter skin with the excessive sun-related changes increases the likelihood of an individual developing skin cancer.

Any trauma or injury to the skin can produce postinflammatory hypo- or hyperpigmentation when injury disrupts the dermal–epidermal junction where most of the melanocytes reside. This can also occur with specific skin disease including the end stage of eczema or dermatitis, lichen planus, or collagen vascular diseases such as lupus erythematosus.” From Ayello, E.A., Sibbald, R.G., Quiambao, P.C.H., Razor, B. “Introducing a Moisture-Associated Skin Assessment Photo Guide for Brown Pigmented Skin,” World Council of Enterostomal Therapists Journal 34(2):18–25, 2014.

(Modified from Skin Inc. The Fitzpatrick Skin Type Classification Scale. November 2007, Available at http://www.skininc.com/skinscience/physiology/10764816.html.)

Moisture Balance

Assess skin for the level of moisture seen externally, or felt on the surface. Too little moisture results in dry, scaly, flaky skin commonly referred to as xerosis (Fig. 4-3). Too much moisture on the skin surface can result in moisture-associated skin damage (MASD). Moisture within the skin tissue (beneath the surface) can result in edema. In the following sections, we will go into more detail on these topics.

Figure 4-3. Xerosis terminology. (A) Mild. Dry skin with minimal flaking. Treatment: Hydrate the skin using a moisturizing agent frequently. (B) Moderate. Dry skin with a scaly, fish-like appearance that’s easily rubbed off the skin surface. Treatment: Use an exfoliating emollient moisturizing agent. (C) Severe. Cracking, parched appearance of skin that resembles dry earth. Treatment: Use moisturizer with urea, AHA, or lactic acid to exfoliate calloused dry skin.

Xerosis

Xerosis is the medical term for dry skin.46 In xerosis, the skin appears dry, scaly, and flaky. Although there is a xerosis scale, it’s not widely used in clinical practice. Clinicians generally classify xerosis as mild, moderate, and severe.

The term xerosis has no particular diagnostic implication. Xerosis can be caused by environmental factors or a symptom of an underlying disease. For this reason, a patient’s complaint of “dry” skin needs to be explored further. Skin exposure to a dry environment, such as central heating, wind, temperature extremes, or air conditioning, can all lead to xerosis.

Management

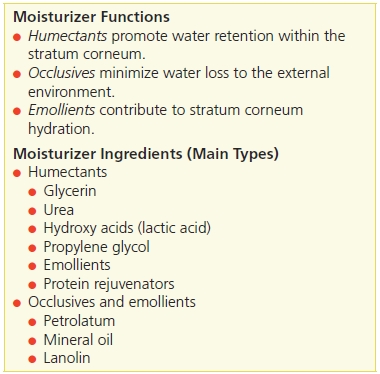

The goal in treating xerosis is to protect the skin from excessive transepidermal water loss (TEWL) and return the natural moisturizing factors to the stratum corneum. This is best accomplished by using moisturizing agents that contain lipids—an essential component in forming an impervious barrier, or seal, on the stratum corneum, thus preventing further water loss (Table 4-5). As water is retained, the skin surface is flattened, and scaling is reduced.46 Patient, family, caregiver instruction on cleansing, environmental factors, and hydration is also important (see Patient Teaching tips)

Table 4-5 Moisturizer Functions and Ingredients

Practice Point

Practice Point

Skin can become dry when TEWL drops below 10%

Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

To avoid xerosis, patients should be given clear instructions regarding cleansing, their environment, and remaining hydrated.

Cleansing

Instruct the patient to:

- avoid long baths (<15 minutes) or consider showering instead

- bathe every other day rather than daily

- use tepid water rather than hot water

- use pH-balanced soaps (4.0 to 6.5), avoid excessive use of deodorant soaps, and rinse well

- avoid vigorously using a washcloth to clean the skin

- pat or blot the skin, rather than rubbing with a towel, so some water is left on the skin

- apply moisturizers immediately after bathing or showering.

Environmental

Instruct the patient to:

- use a humidifier during the winter months when central heating is being used

- drink plenty of water

- wear a sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) of 15 or higher that contains a moisturizer

- use nonfragrant laundry detergents, fabric softeners, and products.

Hydration

Instruct the patient to:

- use moisturizers, applying frequently, using correct gentle application technique for specific product (check product directions on how to use), and implementing fall safety precautions because bathing surfaces may be slippery if using bath oils.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Stop the Xerosis Cycle!

- Dry skin (xerosis)

- Pruritus

- Scratching

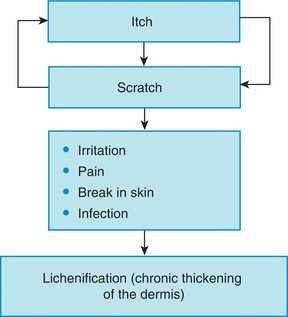

Because many moisturizers dissipate after 3 to 4 hours, these authors recommend using long-lasting moisturizers to cool, soothe, and restore barrier function. The goal is to break the itch–scratch–itch cycle, which happens because dry skin is often itchy, causing patients to scratch their skin. In turn, excessive scratching can ultimately lead to a break in the skin. Once the skin barrier is broken, it becomes a portal of entry for bacteria, which can lead to infection. This repetitive scratching causes chronic thickening of the dermis known as lichenification. Therefore, prompt identification of the itch–scratch–itch cycle as well as teaching the patient about skin damage (from scratching) is extremely important in helping the skin to heal and reducing the occurrence of lichenification (Fig. 4-4).

Figure 4-4. Itch–scratch–itch cycle.

Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

Teach the patient about the itch–scratch–itch cycle.

Pruritus

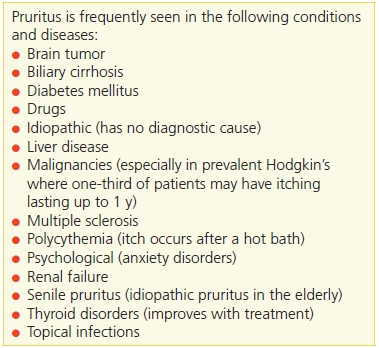

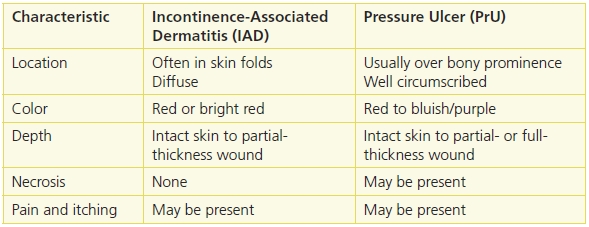

Pruritus is the medical term for itchy skin and is a common symptom for several diseases.5 Therefore, taking a detailed history aids in determining if the cause is from such an underlying disease or if it’s just untreated xerosis. For example, pruritus may be a symptom of renal or liver disease, scabies, or dry skin from aging (Table 4-6). Helping patients understand the itch–scratch–itch cycle and their own behavioral pattern is important to successful management. Treating the person with pruritus incorporates many of the elements in Table 4-7.31

Table 4-6 Pruritus

Adapted with permission from Tomic-Canic, M. “Keratinocyte Cross-Talks in Wounds,” Wounds 17:S3–6, 2005.

Table 4-7 Treatment Plan for Pruritus

Venna, S.S., Gilchrest, B.A. “Skin Aging and Photoaging,” Skin and Aging 12:56–69, 2004.

Gilhar, A., et al. “Ageing of Human Epidermis: The Role of Apoptosis, Fas and Telomerase,” The British Journal of Dermatology 15(1), 2004.

Moisture-Associated Skin Damage

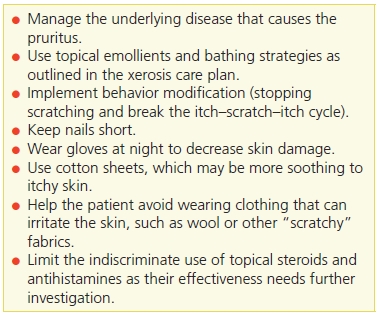

Just as dry skin can be a problem, exposure to excessive moisture can also cause skin damage. Four types of MASD have been defined in the literature: incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD), intertriginous dermatitis (ITD), periwound moisture–associated dermatitis, and peristomal moisture–associated dermatitis.47–55 Common causes of MASD include incontinence of stool and/or urine (IAD), wound exudates (see Chapter 6), fistula or stoma effluent (see Chapter 19), and perspiration, mucus, or saliva.47–50 Skin damage from moisture is distinct from pressure and differentiating the correct etiology between these two types of skin injuries is important for appropriate treatment and prevention50–53 (Table 4-8). It is not clear whether moisture alone or a combination of wetness coupled with irritants within the moisture source causes damage to the skin.50 Classification of gluteal and buttock wounds remains a challenge.54

Table 4-8 Differential Diagnosis of MASD and Pressure Ulcers in the Perineal and Genital Area

Adapted from Gray, M., Bohacek, L., Weir, D., et al. “Moisture vs Pressure. Making Sense out of Perineal Wounds,” Journal of Wound, Ostomy, and Continence Nursing 34(2):134–42, 2007.

Incontinence-Associated Dermatitis

The remainder of this section will focus on MASD caused from incontinence of urine, stool, or both. IAD is sometimes referred to as perineal dermatitis or even in infants as “diaper dermatitis” (Fig. 4-5). Literature50–52 has advocated for the use of the term MASD to identify these skin lesions. IAD is believed to be reversible, begins as persistent redness, and progresses to partial-thickness skin injury but not full-thickness wounds.50 Although there are three IAD instruments discussed in the literature, they are not yet widely used in practice.51

Figure 4-5. Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD). (Photo courtesy of KDS Consulting.)

Gray et al.51 summarized several research studies about prevention of IAD and concluded that a routine perineal skin protocols that avoided soap and used cleansing products with a pH range of normal skin were effective along with reducing skin scrubbing and friction. Use of products that moisturize and protect the skin were recommended.51 Holistic care also requires interventions to address and minimize the episodes of incontinence such as a scheduled toileting program.51 Other strategies to prevent skin exposure to urine or stool include use of containment devices such as condom catheter, anal pouch, or bowel management systems. If absorptive products are used, make sure that they wick urine or stool away from the skin. Recommendations for a structured skin care regimen include cleaning the skin daily and after each incontinence episode using a no-rinse cleanser; not scrubbing the skin; applying humectants or emollient moisturizer; barrier creams; ointments with petroleum, zinc oxide, or dimethicone; or skin sealant products.51–53 If a fungal infection is also present, this will require additional antifungal products.51,53

Intertriginous Dermatitis

Another type of MASD is ITD. It is “the term for skin damage caused by trapped perspiration and frictional forces between opposing skin surface.”54 Clinicians should be looking in skin folds including the inframammary, axillary, and inguinal skin folds as well as the abdominal or pubic panniculi49 (Fig. 4-6). Since skin-to-skin moisture and friction have been hypothesized as the cause of ITD, a high-risk population for ITD is the bariatric and obese patient population. Others at risk include women with large pendulous breasts, persons with stocky necks, and children with skin folds.

Figure 4-6. Intertriginous dermatitis (ITD). Intertrigo between the skin folds of the breast of a female patient with a body mass index of 60. Note the fissure at the base of the skin fold.

As moisture accumulates in a skin fold, the potential for growth of microorganisms exists.56 As skin pH becomes more alkaline, Black et al.49 report that ITD cultures have shown growth of the following organisms: S. aureus, group Aβ-hemolytic streptococcus, Pseudomonas, Proteus mirabilis, Proteus vulgaris, enterococci, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and fungus such as Candida.

Careful assessment of skin folds for ITD is important. Typically, ITD begins as mild, mirror-image erythema of the skin.49 With continued exposure to the moisture, the skin becomes more inflamed and macerated. Skin erosions, oozing, crusting, itching, pain, and odor may be present.49 Efforts to prevent ITD focus on appropriate skin hygiene including keeping the skin clean and dry, using skin pH neutral products, avoiding abrasive and friction using skin care, and “pat” drying the skin. Treatment includes continuing the skin care regimens for cleansing as well as, soaks with various astringent solutions, specialized dressings designed to be placed in skin folds to absorb moisture, and if candidiasis is present to use antifungal powders.49

Edema

Edema is abnormal swelling caused by accumulation of fluid in the tissues.57 Swelling caused by edema commonly occurs in the hands, arms, ankles, legs, and feet (Fig. 4-7). It is usually linked to the venous or lymphatic systems.

Figure 4-7. Assessment of foot edema. (©Ayello and Sibbald, used with permission.)

Edema may be generalized or local. It can appear suddenly but usually develops subtly—the patient may first gain weight, or wake up with puffy eyes. Many patients wait until symptoms are well advanced before seeking medical help.

Assess area for edema by comparing one extremity to another. Press firmly with finger tip, usually index finger, on edematous site for 5 seconds and release (Fig. 4-8). Edema is “pitting” when it does not return to its normal contour rapidly.57 Document the amount of pitting edema that you observe. There is no consensus in how edema is documented. Some use descriptive words such as mild, moderate, or severe, while others use numerical and plus signs (+1, +2, +3, +4), follow your facility policy. Elevate if condition warrants, use care in moving and reposition edematous extremities and use appropriate skin care products. Chapter 14 also includes more advanced information about edematous conditions.

Figure 4-8. Assessing lower leg for edema. (A) Examine lower leg. (B) Using your finger, depress the skin. (C) Remove your finger, note dent in the skin to access edema. (Ayello, E.A., Sibbald, R.G., Quiambao, P.C.H., et al. “Introducing a Moisture-Associated Skin Assessment Photo Guide for Brown Pigmented Skin,” World Council of Enterostomal Therapists Journal 34(2):18–25, 2014. ©Ayello and Sibbald, used with permission.)

Practice Point

Practice Point

Assessing for pitting edema rating scale

1+ equals 2 mm depression

2+ equals 4 mm depression

3+ equals 6 mm depression

4+ equals 8 mm depression

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree