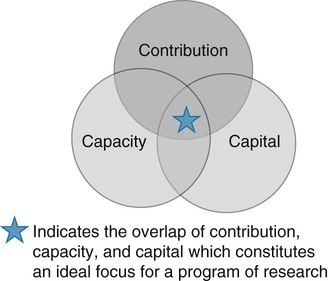

An aspiring career researcher needs to initiate a program of research in a specific area of study and seek funding in this area. A program of research consists of the studies that a researcher conducts, starting with small, simple studies and moving to larger, complex studies over time. For example, if your research interest is to promote health in rural areas, you need to plan a series of studies that focus on promoting rural health. Early studies may be small with each single successive study building on the findings of the previous study. Finckeissen (2008) described this approach as having a meta-model of research with alternative solutions to a research problem. The findings of each study suggest new solutions or provide evidence that another solution is ineffective. Dr. Jean McSweeney, PhD, RN, FAHA, FAAN, Professor at the College of Nursing, University of Arkansas of Medical Sciences, is an example of a nurse researcher who has built a program of research. Dr. McSweeney’s area of clinical practice was critical care, and she became very interested in cardiac patients. To complete her PhD, she conducted a qualitative study with patients and their significant others to explore behavior changes after a myocardial infarction. Her first post-dissertation study was a qualitative study of women’s motivations to change their behavior after a myocardial infarction. She continued by conducting a series of quantitative studies that built on the findings of the previous studies. Table 29-1 lists publications by Dr. McSweeney that indicate the trajectory of her research program. Publication of the studies increased the credibility of the researcher and provided the foundation for future funding. TABLE 29-1 Citations from Oldest to Most Recent McSweeney, J. C. (1993). Explanatory models of a myocardial event: Linkages between perceived causes and modifiable health behaviors. Rehabilitation Nursing Research, 2(1), 39–49. McSweeney, J. C. & Crane, P. B. (2001). An act of courage: Women’s decision-making processes regarding outpatient cardiac rehabilitation attendance. Rehabilitation Nursing, 26(4), 132–140. Crane, P. B. & McSweeney, J. C. (2003). Exploring older women’s lifestyle changes after myocardial infarction. Medsurg Nursing, 12(3), 170–076. McSweeney, J. C., Cody, M., O’Sullivan, P., Elberson, D., Moser, D. K., & Gavin, B. J. (2003). Women’s early warning symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Circulation, 108(21), 2619–2623. McSweeney, J. C., O’Sullivan, P., Cody, M., Crane, P. B. (2004). Development of the McSweeney Acute and Prodromal Myocardial Infarction Symptom Survey. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19(1), 58–67. McSweeney, J. C. & Coon, S. (2004). Women’s inhibitors and facilitators associated with making behavioral changes after myocardial infarction. Medsurg Nursing, 13(1), 49–56. McSweeney, J. C., Lefler, L. L., & Crowder, B. F. (2005). What’s wrong with me? Women’s coronary heart disease diagnostic experiences. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(2), 48–57. McSweeney, J. C., Lefler, L. L., Fischer, E. P., Naylor, A. J., & Evans, L. K. (2007). Women’s prehospital delay associated with myocardial infarction: Does race really matter? The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 22(4), 279–285. McSweeney, J. C., Pettey, C. M., Fischer, E. P., & Spellman (2009). Going the distance. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 2(4), 256–264. McSweeney, J. C., Cleves, J. A., Zhao, W., Lefler, L. L., & Yang, S. (2010). Cluster analysis of women’s prodromal and acute myocardial infarction by race and other characteristics. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25(4), 104–110. McSweeney, J. C., O’Sullivan, P., Cleves, M. A., Lefler, L. L., Cody, M., et al. (2010). Racial differences in women’s prodromal and acute symptoms of myocardial infarction. American Journal of Critical Care, 19(1), 63–73. Beck, C., McSweeney, J. C., Richards, K. C., Roberson, P. K., Tsai, P.-F., & Souder, E. (2010). Challenges in tailored intervention research. Nursing Outlook, 58(2), 104–110. McSweeney, J. C., Pettey, C. M., Souder, E., & Rhoads, S. (2011). Disparities in women’s cardiovascular health. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 40(3), 362–371. How do you decide on the focus of your program of research? The ideal focus of a program of research is the intersection of a potential contribution to science, your capacity, and the capital that you can assemble. Figure 29-1 shows the ideal study as overlapping circles of contribution, capacity, and capital. Networking is a process of developing channels of communication among people with common interests who may not work for the same employer or may be geographically scattered. Contacts may be made through social media, computer networks, mail, telephone, or arrangements to meet at a conference (Adegbola, 2011). Strong networks are based on reciprocal relationships. A professional network can provide opportunities for brainstorming, sharing ideas and problems, and discussing grant-writing opportunities. In some cases, networking may lead to the members of a professional network writing a grant that will be a multisite study with data collected in each member’s home institution. When a proposal is being developed, the network, which may become a reference group, can provide feedback at various stages of development of the proposal. Adegbola (2011) provides practical tips on how to develop and maintain a professional network. Through networking, nurses interested in a particular area of study can find peers, content experts, and mentors. A content expert may be a clinician or researcher who is known for his or her work in the area in which you are also interested. Through your review of the literature, you identify a researcher who has developed an instrument to measure a variable that you have decided must be included in your proposed study. For example, you want to measure a biological marker of stress and you have read several studies in which an experienced researcher measured the variable using a specific piece of equipment. You can also search the Virginia Henderson International Nursing Library to find funded and unfunded researchers on different topics (http://www.nursinglibrary.org/vhl/pages/aboutus.html). Contact the researcher through email to make a telephone appointment to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of this particular measurement, or you may arrange to meet at an upcoming conference. A mentor is a person who is more experienced professionally and willing to work with a less experienced professional to achieve his or her goals. Because funded nursing researchers are few, the need for mentoring is greater than the number of available mentors (Maas, Conn, Buckwalter, Herr, & Tripp-Reimer, 2009). Finding a mentor may take time and require significant effort. Much of the information needed is transmitted verbally, requires actual participation in grant-writing activities, and is best learned in a mentor relationship. This type of relationship requires a willingness by both professionals to invest time and energy. A mentor relationship has characteristics of both a teacher-learner relationship and a close friendship. Each individual must have an affinity for the other, from which a close working relationship can be developed. The relationship usually continues for a long period.

Seeking Funding for Research

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Building a Program of Research

Getting Started

Level of Commitment

Support of Other People

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access