The rate of new knowledge being generated each year continues to grow. Early studies in the 1960s indicated that knowledge doubled every 13 to 15 years (Larsen & von Ins, 2010). The vast amount of information available within seconds implies that knowledge is doubling much more rapidly in the digital age. Bachrach (2001) noted that each new discipline launches new journals to develop its disciplinary knowledge. Computerized bibliographical databases have made the process of searching for relevant empirical or theoretical literature easier in some ways, but you are faced with the dilemma of selecting the most relevant sources from a much larger number of articles. The task of reading, critically appraising, analyzing, and synthesizing has expanded and can consume any time gained by more efficient searching. This chapter provides basic skills and knowledge to identify evidence for changing nursing practice, developing a research proposal, preparing a lecture, or writing a manuscript. The literature review is an organized written presentation of what you find when you review the literature. The literature review is “central to scholarly work and disciplined inquiry” (Holbrook, Bourke, Fairbairn, & Lovat, 2007, p. 337); it summarizes what has been published on a topic by scholars and presents relevant research findings. Developing the ability to write coherently about what you have found in the literature requires time and guidance. The review should be organized into sections that present themes, identify trends, or examine variables. The purpose is not to list all the material published but, rather, to synthesize and evaluate it on the basis of the phenomenon of interest. For most course papers, your instructor will expect you to review published sources on the topic of your paper. Reviews of the literature for a course assignment will vary depending on the level of educational program, the purpose of the assignment, and the expectations of the instructor. The literature review for a graduate course is expected to have greater depth, scope, and breadth than a review for an undergraduate course (Hart, 2009). A paper in a nurse practitioner course might require that you review pharmacology and pathology reference books in addition to journal articles. In a nursing education course, you may review neurological development, cognitive science, and general education publications to write a paper on a teaching strategy. For a doctor of nursing practice course on clinical information systems, your review might need to extend into computer science and hospital management literature. For a theory course in a doctor of philosophy in nursing program, your review may need to include all the publications of a specific theorist or all the studies based on the theory. For each of these papers, your professor may specify the publication years and the type of literature to be included. Also, you must note the acceptable length of the written review of the literature to be submitted. Reviews of the literature for course assignments tend to focus on what is known, the strength of the evidence, the implications of the knowledge, and what is not known for the purpose of developing new studies. Evidence-based practice guidelines are developed through the synthesis of the literature on the clinical problem. The purpose of the literature review designed to examine the strength of the evidence is to identify all studies that provide evidence of a particular intervention, to critically appraise the quality of each study, and to synthesize all of the studies providing evidence of the effectiveness of a particular intervention. It is also important to locate and include previous evidence-based papers that have examined the evidence of a particular intervention, because the conclusions of the authors of such papers are highly relevant. Literature syntheses related to promoting evidence-based nursing practice are described in Chapter 19. In qualitative research, the purpose and timing of the literature review depend on the type of study to be conducted (see Chapter 12). Some phenomenologists believe that the literature should not be reviewed until after the data have been collected and analyzed, so that the literature does not interfere with the researcher’s ability to suspend what is known and to approach the topic with openness (Munhall, 2012). In the development of a grounded theory study, a minimal review of relevant studies provides the beginning point of the inquiry, but this review is only a means of making the researcher aware of what studies have been conducted. This information, however, is not used to direct the collection of data or interpretation of the findings in a grounded theory study. During the data analysis stage, a core variable is identified and the researcher theoretically samples the literature for extant theories that may assist in explaining and extending the emerging theory (Munhall, 2012). In historical research, the initial review of the literature helps the researcher define the study questions and make decisions about relevant sources. The data collection is actually an intense review of published and unpublished documents that the researcher has found. The purposes of reviewing the literature for ethnographic studies and for exploratory descriptive qualitative research are more similar to that for quantitative research. The researcher develops a general understanding of the concepts to be examined in relation to the selected culture or topic. The literature review also provides a background for conducting the study and interpreting the findings. Chapter 12 describes in more detail the role of the literature review in qualitative research. Table 6-1 describes the role of the literature throughout the development and implementation of the study. The types of sources needed and how you will search the literature will vary throughout the study. The introduction section uses relevant sources to summarize the background and significance of the research problem. The review of the literature section includes both theoretical and empirical sources that document the current knowledge of the problem. The researcher develops the framework section from the theoretical literature and sometimes from empirical literature. If little theoretical literature is found, the researcher may need to develop a tentative theory to guide the study from the findings of previous research studies (see Chapter 7 for more information). The methods section describes the design, sample, measurement methods, treatment, and data collection process of the planned study and is based on previous research. Thus, previous studies may be cited in the methods section. In the results section, sources are included to document the different types of statistical analyses conducted and the computer software to conduct these analyses. The discussion section of the research report begins with what the results mean in light of the results of previous studies. Conclusions are drawn that are a synthesis of the cited findings from previous research and those from the present study. TABLE 6-1 The Role of the Literature Review in Developing a Quantitative Research Proposal Two broad types of literature are cited in the review of literature for research: theoretical and empirical. Theoretical literature consists of concept analyses, models, theories, and conceptual frameworks that support a selected research problem and purpose. Empirical literature comprises knowledge derived from research. The empirical literature reviewed depends on the study problem and the type of research conducted. Research problems that have been frequently studied or are currently being investigated have more extensive empirical literature than new or unique problems. If searching the empirical literature, you need to identify seminal and landmark studies. Seminal studies are the first studies that prompted the initiation of the field of research. Nurse researchers studying hearing loss in infants would need to review the seminal work of Fred H. Bess, an early researcher on this topic who advocated for effective screening tools (Gravel, 2009). Critical care nurses comparing correction formulas for QT intervals on electrocardiograms would want to refer to Bazet’s correction formula. The development of the formula can be traced to his seminal paper, published in 1920, on time-relations in electrocardiograms (Roguin, 2011). Landmark studies are the studies that led to an important development or a turning point in the field of research. For example, researchers conducting studies related to glycemic control must be knowledgeable of the implications of the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, a longitudinal study whose findings changed diabetic care beginning in the mid-1990s (Everett, Bowes, & Kerr, 2010). Entire volumes of books available in a digital or electronic format are called eBooks (Tensen, 2010). You may be familiar with digital books in the mass publication literature that are available to download to read on a special reading device, such as a Kindle or Nook. eBooks are also available for scholarly volumes and articles that can be downloaded to a reading device, cell phone, laptop, or other computer. Books that in the past would have been difficult to obtain through interlibrary loan are now available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week as eBooks. To develop the significance and background section of a proposal, you may also need to search for government reports for the United States (U.S.) and other countries, if appropriate for your study. A researcher developing a proposal on task shifting in HIV care settings in low-resource countries would search the Ministry of Health websites for those countries to find official guidelines for this type of practice. Researchers developing a proposal in Wisconsin on the smoking cessation in adolescents would consult the Healthy People 2020 website for the national goals related to this topic (http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx/). They may also explore health-related agencies in Wisconsin to determine information specific to their state. Position papers are disseminated by professional organizations and government agencies to promote a particular viewpoint on a debatable issue. Position papers, along with descriptions of clinical situations, may be included in the discussion of the background and significance of the research problem. A researcher developing a proposal on race-related differences in HIV treatment outcomes would want to review the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care position paper, “Health Disparities,” which the organization’s board approved in 2009. Master’s theses and doctoral dissertations are valuable literature as well but may not be published. A thesis is a research project completed as part of the requirements for a master’s degree. A dissertation is an extensive, usually original research project that is completed as the final requirement for a doctoral degree. Theses and dissertations can be found by searching special databases that are available for these publications, such as ProQuest Dissertations and Theses (http://www.proquest.com/en-US/default.shtml/). The stages of a literature review reflect a systems model. Systems have input, throughput, and output. The input consists of the sources that you find through searching the literature. The throughput is the processes you use to read, critically appraise, analyze, and synthesize the literature you find. The written literature review is the output of these processes (see Figure 6-1). The quality of the input and throughput will determine the quality of the output. As a result, each stage of the literature review is critical to producing a high-quality literature review. Although these stages are presented here as sequential, you may go back to a previous stage. For example, during the analysis and synthesis of your sources, you identify that the studies you are citing were conducted only in Europe. You might go back and search the literature again using the United States or another search term to ascertain that no studies have been done in that country. As you are writing your literature review, you may identify a problem with the logic of your presentation. To resolve it, you may return to the processing stage to clarify the presentation. Before writing a literature review, you must first perform literature searches to identify sources relevant to your topic of interest. The literature review will help you narrow your topic and develop a feasible study (Hart, 2009). Whether you are a student, practicing nurse, or nurse researcher, your goal is to develop a search strategy designed to retrieve as much of the relevant literature as possible given the time and financial constraints of your project. Libraries have become gateways to information or information resource centers, rather than storehouses of knowledge (Hart, 2009). High-quality libraries provide access to a large number of electronic databases that supply a broad scope of the literature available internationally, enabling library users not only to identify relevant sources quickly but also to read full-text versions of most of these sources immediately. When your library does not have the hard copy of a book or electronic access to a specific journal, the librarian can usually provide the book or an electronic copy of the article through interlibrary loan. All libraries, public, private, college, and university, have interlibrary loan capabilities. You may especially need to use interlibrary loan when sources relevant to your topic were published prior to the advent of electronic databases. Consider consulting with an information professional, such as a subject specialist librarian, to develop a literature search approach (Booth, Colomb, & Williams, 2008; Tensen, 2010). Often these consultations can be performed via email or a web-based meeting, so that communication occurs at the convenience of both the researcher and the information professional. Many university libraries provide this consultation service whether or not the library user is affiliated with the university. Before you begin searching the literature, you must consider exactly what information you are seeking. Expending time and effort in the early stage of a review to develop a search strategy is likely to save time and effort later (Hart, 2009). A written plan helps you to avoid duplication of effort, to return to a previously searched area with a different set of search terms or a different range of publication years. Your initial search should be based on the widest possible interpretation of your topic. This strategy enables you to envision the extent of the relevant literature. As you see the results of the initial searches and begin reading the material, you will refine your topic, and then you can narrow the focus of your searches. As you search, add your selected search terms to your written search plan. As you search, add other terms that you discover from the references you locate. For each search, record (1) the name of the database, (2) the date, (3) search terms and searching strategy, (4) the number and types of articles found, and (5) an estimate of the proportion of the citations you retrieved that were relevant articles. Table 6-2 is an example of search history that you can use to record what and how you have searched the literature. Save the results of each search on your computer or external device. Some databases allow you to create an account and save your search history online (i.e., the record of what and how you searched). TABLE 6-2 Plan and Record for Searching the Literature A database is computer data that have been collected and arranged to be searchable and automatically retrievable (Tensen, 2010). A bibliographical database is an “an electronic version of a bibliographic index” (p. 57) or compilation of citations. The database may consist of citations relevant to a specific discipline or may be a broad collection of citations from a variety of disciplines. Databases of periodical citations include the authors, title, journal, keywords, and usually an abstract of the article. Library databases contain titles and authors of hard copy books and documents, government reports, and reference books. Library databases also include a searchable list of the journals to which the library has a paper or electronic subscription. For example, your library may have received paper copies of a monthly journal in the mail until 2006. The hard copies of the issues were bound to create annual volumes of the journal. Since 2006, the library has subscribed to the electronic journal or a journal database that provides access to specific issues. Older sources of reference indexes are useful for sources published prior to the electronic databases. Card catalogs, abstract reviews, and indexes were the only ways to search for nursing references until 1955, when the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) began being published. Because the printed editions had red covers, you still may hear more experienced scholars fondly refer to “the Red Books.” The print version of CINAHL is still available in libraries, and you may find it useful when searching for citations published before 1982 or when bibliographic databases are not available (Tensen, 2010). In medicine, the Index Medicus (IM) was first published in 1879 and is the oldest health-related index. The Index Medicus includes some citations of nursing publications, with the number of nursing journals cited growing. CINAHL contains, however, a more extensive listing of nursing publications and uses more nursing terminology as subject headings. With the greater focus on interdisciplinary research, nurse researchers must also be consumers of the literature in the National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE), other government agencies, and professional organizations. Table 6-3 provides descriptions of commonly used bibliographical databases. TABLE 6-3 *Direct quotations from EBSCO Publishing descriptions of the databases, available at http://www.ebscohost.com/academic/.

Review of Relevant Literature

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

What Is a Literature Review?

Purposes of Reviewing the Literature

Writing a Course Paper

Examining the Strength of the Evidence

Developing a Qualitative Research Proposal

Developing a Quantitative Study

Phase of the Research Process

How Literature Is Used and Its Role

Research topic

Broad searches using keywords to understand the extent of what is known and what is not known; what concepts are related to the topic

Statement of the research purpose

From your synthesis of the literature, the specific gap in knowledge that this study will address

Background and significance

Searches of books and articles to provide an overview of the topic

Identification of the size, cost, and consequences of the research problem

Research framework

Find and read relevant theories

Facilitate development of the framework

Develop conceptual definitions of concepts

Purpose of the study

On the basis of your knowledge of the literature, state the purpose of the study

Research objectives, questions, or hypotheses

On the basis of the knowledge gained from and examples found in the literature, write the objectives or questions of the study

If sufficient literature allows a prediction, state the hypotheses of the study

Review of the literature

Find sources as evidence for logical argument for why this study and methodology are needed

Summarize current empirical knowledge that is related to the topic

Methodology

Compare research designs of reviewed studies to select the most appropriate design for the proposed study

Identify possible instruments or measures of variables

Provide operational definitions of concepts

Describe performance of measures in previous studies

Develop sampling strategies based on what you have learned from the studies in the literature

Findings

Refer to statistical textbooks to explain the results of the data analysis

Discussion

Compare your findings with those of studies you have previously reviewed

Return to the literature to find new references to interpret unexpected findings

Identify limitations of the study

Refer to theory sources to relate the findings to the research framework

Conclusions

On basis of your knowledge of the literature and your study’s findings, draw conclusions

Discuss implications for nursing clinical practice, administration, and education

Propose future studies

Practical Considerations

What Types of Literature Can I Expect to Find?

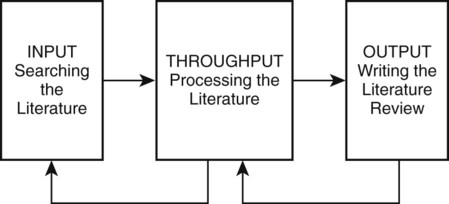

Stages of a Literature Review

Searching the Literature

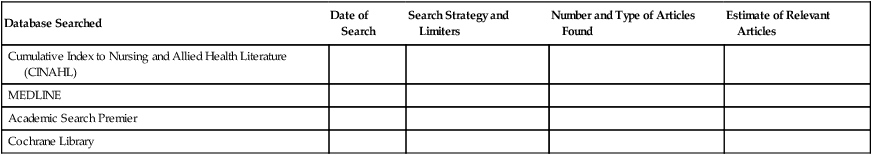

Develop a Search Plan

Database Searched

Date of Search

Search Strategy and Limiters

Number and Type of Articles Found

Estimate of Relevant Articles

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

MEDLINE

Academic Search Premier

Cochrane Library

Select Databases to Search

Name of Database

Description of the Database by the Publisher*

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

“Comprehensive source of full text for nursing & allied health journals, providing full text for more than 770 journals”

MEDLINE

“Information on medicine, nursing, dentistry, veterinary medicine, the health care system, pre-clinical sciences, and much more”

Created and provided by the National Library of Medicine

Uses Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) for indexing and searching of “citations from over 4,800 current biomedical journals”

PubMed

Free access to Medline that provides links to full-text articles when available

PsychARTICLES

15,000 “full-text, peer-reviewed scholarly and scientific articles in psychology”

Limited to journals published by the American Psychological Association (APA) and affiliated organizations

PsychINFO

“Scholarly journal articles, book chapters, books, and dissertations, is the largest resource devoted to peer-reviewed literature in behavioral science and mental health”

Supported by APA

Covers over 3 million records

Academic Search Complete

“Comprehensive scholarly, multi-disciplinary full-text database, with more than 8,500 full-text periodicals, including more than 7,300 peer-reviewed journals”

Health Source Nursing/ Academic Edition

“Provides nearly 550 scholarly full text journals focusing on many medical disciplines”

Also includes 1,300 patient education sheets for generic drugs

Psychological and Behavioral Sciences Collection

“Comprehensive database covering information concerning topics in emotional and behavioral characteristics, psychiatry & psychology, mental processes, anthropology, and observational & experimental methods”

400 journals indexed

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Review of Relevant Literature

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access