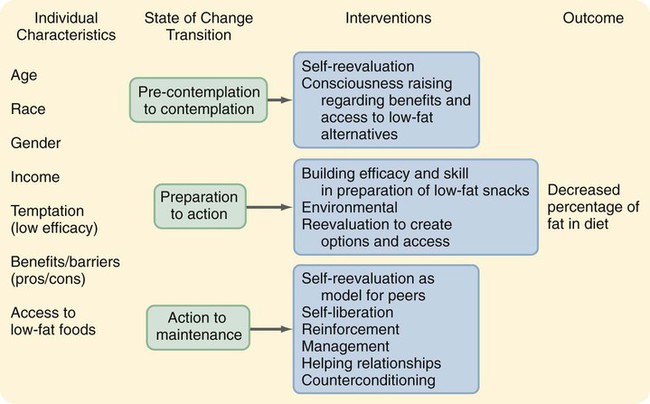

By questioning and reviewing the literature, researchers begin to recognize a specific area of concern and the knowledge gap that surrounds it. The knowledge gap, or what is not known about this clinical problem, determines the complexity and number of studies needed to generate essential knowledge for nursing practice (Craig & Smyth, 2012; Creswell, 2009). In addition to the area of concern, the research problem identifies a population and sometimes a setting for the study. A research problem includes significance, background, and a problem statement. The significance of a problem indicates the importance of the problem to patients and families, nursing, healthcare system, and society. The background for a research problem briefly identifies what we know about the problem area. The problem statement identifies the specific gap in the knowledge needed for practice. A research problem from the study by Grady, Entin, Entin, and Brunye (2011) is presented as an example. This study was conducted to examine the effectiveness of educational messages or information on the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of people with diabetes. In this example, the research problem identifies an area of concern (incidence, costs, and complications of diabetes) for a particular population (persons with diabetes) in selected settings (inpatient and outpatient venues). Grady and colleagues (2011) clearly identified the significance of the problem, which is extensive and relevant to patients, families, nursing, healthcare system, and society. The problem background focuses on key research conducted to examine the effectiveness of health education on the management of diabetes. The last sentence in this example is the problem statement, which identifies the gap in the knowledge needed for practice. In this study, there is limited research on how to present diabetic education to maximize its effectiveness on attitudinal and behavioral change in people with this chronic illness. The research purpose is a clear, concise statement of the specific focus or aim of the study that is generated on the basis of the research problem. The purpose usually indicates the type of study (quantitative, qualitative, outcomes, or intervention) to be conducted and often includes the variables, population, and setting for the study. The goals of quantitative research include identifying and describing variables, examining relationships among variables, and determining the effectiveness of interventions in managing clinical problems (Creswell, 2009; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). The goals of qualitative research include exploring a phenomenon, such as depression as it is experienced by pregnant women; developing theories to describe and manage clinical situations; examining the health practices of certain cultures; describing health-related issues, events, and situations; and determining the historical evolution of the profession (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012). The focus of outcomes research is to identify, describe, and improve the outcomes or end results of patient care (Doran, 2011). Intervention research focuses on investigating the effectiveness of nursing interventions in achieving the desired outcomes in natural settings (Forbes, 2009). Regardless of the type of research, every study needs a clearly expressed purpose statement to guide it. Grady et al. (2011) clearly identified their study purpose following their research problem statement of the gap in the knowledge base. Thus, the purpose of their study was to “examine the impact of information framing in an educational program about proper foot care and its importance for preventing diabetic complications on long-term changes in foot care knowledge, attitudes, and behavior” (Grady et al., 2011, p. 23). This research purpose indicates that these investigators conducted a quantitative quasi-experimental study to determine the effectiveness of an independent variable or intervention (information framing educational program about diabetic foot care and prevention of complications) on the dependent or outcome variables (foot care knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors). The researchers also identified two hypotheses to direct their study, which included the four variables identified (see Chapter 8 for a discussion of hypotheses). The study findings indicated that the gain-framed messages focused on the benefits of taking action were significantly more effective in promoting positive behavioral changes in people with diabetes than the loss-framed messages focused on the costs of not taking action. A gain-framed message might be stated as follows: “Achieving normal blood sugar increases your feelings of health and well being and promotes control of your illness.” A loss-framed message might be worded as follows: “Poorly controlled blood sugars can lead to complications of neuropathy, foot lesions, and amputation.” Grady et al. (2011) also found that changes in knowledge affected changes in attitudes and that attitudes were direct predictors of long-term behavior management of diabetes. The findings from this study and other research provide evidence of the effectiveness of information messages in sustaining health promoting behavior by people with diabetes. Because health care is constantly changing in response to consumer needs and trends in society, the focus of current research varies according to these needs and trends. For example, research evidence is needed to improve practice outcomes for infants and new mothers, the elderly and residents in nursing homes, and persons from vulnerable and culturally diverse populations. Healthcare agencies would benefit from studies of varied healthcare delivery models. Society would benefit from interventions recognized to promote health and prevent illness. In summary, clinically focused research is essential if nurses are to develop the knowledge needed for evidence-based practice (EBP) (Brown, 2009; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Interactions with researchers and peers offer valuable opportunities for generating research problems. Experienced researchers serve as mentors and help novice researchers to identify research topics and formulate problems. Nursing educators assist students in selecting research problems for theses and dissertations. When possible, students conduct studies in the same area of research as the faculty. Faculty members can share their expertise regarding their research program, and the combined work of the faculty and students can build a knowledge base for a specific area of practice. This type of relationship could also be developed between an expert researcher and a nurse clinician. Because nursing research is critical for designation as a Magnet facility by the American Nurses Credentialing Center© (ANCC, 2012), hospitals and healthcare systems employ nurse researchers for the purpose of guiding studies conducted by staff nurses. Building an EBP for nursing requires collaboration between nurse researchers and clinicians as well as with researchers from other health-related disciplines. Interdisciplinary research teams have the expertise to increase the quality and quantity of studies conducted. Being a part of a research team is an excellent way to expand your understanding of the research process. Beveridge (1950) identified several reasons for discussing research ideas with others. Ideas are clarified and new ideas are generated when two or more people pool their thoughts. Interactions with others enable researchers to uncover errors in reasoning or information. These interactions are also a source of support in discouraging or difficult times. In addition, another person can provide a refreshing or unique viewpoint, which helps avoid conditioned thinking, or following an established habit of thought. A workplace that encourages interaction can stimulate nurses to identify research problems. Nursing conferences and professional meetings also provide excellent opportunities for nurses to discuss their ideas and brainstorm to identify potential research problems. Reviewing research journals, such as Advances in Nursing Science, Applied Nursing Research, Clinical Nursing Research, Evidence-Based Nursing, International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing Research, Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Journal of Advanced Nursing, Journal of Research in Nursing, Nursing Research, Nursing Science Quarterly, Research in Nursing & Health, Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research, and Western Journal of Nursing Research, as well as theses and dissertations will acquaint novice researchers with studies conducted in an area of interest. The nursing specialty journals, such as American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, Dimensions of Critical Care, Heart & Lung, Infant Behavior and Development, Journal of Pediatric Nursing, and Oncology Nursing Forum, also place a high priority on publishing research findings. Reviewing research articles enables you to identify an area of interest and determine what is known and not known in this area. The gaps in the knowledge base provide direction for future research. (See Chapter 6 for the process of reviewing the literature.) At the completion of a research project, an investigator often makes recommendations for further study. These recommendations provide opportunities for others to build on a researcher’s work and strengthen the knowledge in a selected area. For example, the Grady et al. (2011, p. 27) study, introduced earlier in this chapter, provided recommendations for further research to examine “the longer term eventualities of gain- and loss-framed messages on preventative behaviors.” They also recommended examining how long the gain-framed message might last and when it would be “necessary to provide another message presentation to bolster effective self-care behavior” (p. 27). These researchers also encouraged others to validate their findings through replication studies that varied the content and delivery format of educational messages provided persons with diabetes. Reviewing the literature is a way to identify a study to replicate. Replication involves reproducing or repeating a study to determine whether similar findings will be obtained (Fahs, Morgan, & Kalman, 2003). Replication is essential for knowledge development because it (1) establishes the credibility of the findings, (2) extends the generalizability of the findings over a range of instances and contexts, (3) reduces the number of type I and type II errors, (4) corrects the limitations in studies’ methodologies, (5) supports theory development, and (6) lessens the acceptance of erroneous results. Some researchers replicate studies because they agree with the findings and wonder whether the findings will hold up in different settings with different subjects over time. Others want to challenge the findings or interpretations of prior investigators. Some researchers develop research programs focused on expanding the knowledge needed for practice in an area. This program of research often includes replication studies that strengthen the evidence for practice. Four different types of replications are important in generating sound scientific knowledge for nursing: (1) exact, (2) approximate, (3) concurrent, and (4) systematic extension (Haller & Reynolds, 1986). An exact (or identical) replication involves duplicating the initial researcher’s study to confirm the original findings. All conditions of the original study must be maintained; thus, “there must be the same observer, the same subjects, the same procedure, the same measures, the same locale, and the same time” (Haller & Reynolds, 1986, p. 250). Exact replications might be thought of as ideal to confirm original study findings, but these are frequently not attainable. In addition, one would not want to replicate the errors in an original study, such as small sample size, weak design, or poor-quality measurement methods. For a concurrent (or internal) replication, the researcher collects data for the original study and the replication study simultaneously thereby checking the reliability of the original study findings. The confirmation, through replication of the original study findings, is part of the original study’s design. For example, your research team might collect data simultaneously at two different hospitals to compare and contrast the findings. Consistency in the findings increases the credibility of the study and the likelihood that others will be able to generalize the findings. Some expert researchers obtain funding to conduct multiple concurrent replications, in which a number of individuals conduct repetitions of a single study, but with different samples in different settings. Clinical trials that examine the effectiveness of the pharmacological management of chronic illnesses, such as diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, are examples of concurrent replication studies. As each study is completed, the findings are compiled in a report that specifies the series of replications that were conducted to generate these findings. Some outcome studies involve concurrent replication to determine whether the outcomes vary for different healthcare providers and healthcare settings across the United States (Brink & Wood, 1979; Brown, 2009; Doran, 2011). A systematic (or constructive) replication is done under distinctly new conditions. The researchers conducting the replication do not follow the design or methods of the original researchers; rather, the second investigative team identifies a similar problem but formulates new methods to verify the first researchers’ findings (Haller & Reynolds, 1986). The aim of this type of replication is to extend the findings of the original study and test the limits of the generalizability of such findings. Intervention research might use this type of replication to examine the effectiveness of various interventions devised to address a practice problem. Nurse researchers need to actively replicate studies to develop strong research evidence for practice. However, the number of nursing studies replicated continues to be limited. The replications of studies might be limited because (1) some view replication as less scholarly or less important than original research, (2) the discipline of nursing lacks adequate resources and funding for conducting replication studies, and (3) editors of journals publish fewer replication studies than original studies (Fahs et al., 2003). However, the lack of replication studies severely limits the generation of sound research findings needed for EBP in nursing. Thus, replicating a study should be respected as a legitimate scholarly activity for both expert and novice researchers. Funding from both private and federal sources is needed to support the conduct of replication studies, with a commitment from journal editors to publish these studies. Theories are an important source for generating research problems because they set forth ideas about events and situations in the real world that require testing (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). In examining a theory, you may note that it includes a number of propositions and that each proposition is a statement of the relationship of two or more concepts. A research problem and purpose could be formulated to explore or describe a concept or to test a proposition from a theory. Middle range theories are the ones most commonly used as frameworks for quantitative studies and are tested as part of the research process (Smith & Liehr, 2008). In qualitative research, the purpose of the study might be to generate a theory or framework to describe a unique event or situation (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012). Some researchers combine ideas from different theories to develop maps or models for testing through research. The map serves as the framework for the study and includes key concepts and relationships from the theories that the researchers want to study. Frenn, Malin, and Bansal (2003, p. 38) conducted a quasi-experimental study to examine the effectiveness of a “4-session Health Promotion/Transtheoretical Model-guided intervention in reducing percentage of fat in the diet and increasing physical activity among low- to middle-income culturally diverse middle school students.” The intervention was based on the “components of two behaviorally based research models that have been well tested among adults—Health Promotion Model (Pender, 1996) and Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska, Norcross, Fowler, Follick, & Abrams, 1992)—but have not been tested regarding low-fat diet with middle school-aged children” (Frenn et al., 2003, p. 36). They developed a model of the study framework (see Figure 5-1) and described the concepts and propositions from the model that guided the development of different aspects of their study. Frenn et al. (2003) used the Pender (1996) Health Promotion Model and the Transtheoretical Model (Prochaska et al., 1992), which are middle range theories, to develop the following research questions to guide their study: The findings from a study either support or do not support the relationships identified in the model. The study by Frenn et al. (2003) added support to the Health Promotion/Transtheoretical Model with their findings that the classroom intervention decreased dietary fat and increased physical activity for middle school–age adolescents. Further research is needed to determine whether classroom interventions over time reduce body mass index, body weight, and the percentage of body fat of overweight and obese adolescents. As a graduate student, you could use this model as a framework and test some of the relationships in your clinical setting. Since 1975, expert researchers, specialty groups, professional organizations, and funding agencies have identified nursing research priorities. The research priorities for clinical practice were initially identified in a study by Lindeman (1975). Those original research priorities included nursing interventions related to stress, care of the aged, pain management, and patient education. Developing evidence-based nursing interventions in these areas continues to be a priority. Many professional nursing organizations use websites to communicate their current research priorities. For example, the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) determined initial research priorities for this specialty in the early 1980s (Lewandowski & Kositsky, 1983) and revised these priorities on the basis of patients’ needs and the changes in health care. The current AACN (2011) research priorities are identified on this organization’s website as (1) effective and appropriate use of technology to achieve optimal patient assessment, management, or outcomes, (2) creation of a healing, humane environment, (3) processes and systems that foster the optimal contribution of critical care nurses, (4) effective approaches to symptom management, and (5) prevention and management of complications. AACN (2011) has also identified future research needs under the following topics: medication management, hemodynamic monitoring, creating healing environments, palliative care and end-of-life issues, mechanical ventilation, monitoring of neuroscience patients, and noninvasive monitoring. If your specialty is critical care, this list of research needs might help you identify a priority problem and purpose for study. The American Organization of Nurse Executives (AONE, 2012) provides a discussion of their education and research priorities online at http://www.aone.org/education/index.shtml/. For 2011-2012, AONE identified more than 25 research priorities in four strategic areas: (1) design of future patient care delivery systems, (2) healthful practice environments, (3) leadership, and (4) the positioning of nurse leaders as valued healthcare executives and managers. To promote the design of future patient care delivery systems, AONE encourages research focused on new technology, patient safety, and the work environment that allows strategies for improvement crucial to the success of the delivery system. In the area of healthful practice environments, AONE encourages research focused on practice environments that attract and retain nurses and that promote professional growth and continuous learning, including mentoring of staff nurses and nursing leaders. In the area of leadership, AONE encourages research focused on evidence-based leadership capacity, measurement of patient care quality outcomes, and technology to complement patient care. To promote the positioning of nurse leaders as valued healthcare executives and managers, AONE encourages research focused on patient safety and quality, disaster preparedness, and workforce shortages. AONE recognizes the importance of supporting education and research initiatives to create a healthy work environment, a quality healthcare system, and strong nurse executives. You can search online for the research priorities of other nursing organizations to help you identify priority problems for study. A significant funding agency for nursing research is the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR). A major initiative of the NINR is the development of a national nursing research agenda that involves identifying nursing research priorities, outlining a plan for implementing priority studies, and obtaining resources to support these priority projects. The NINR has an annual budget of more than $90 million, with approximately 74% of the budget used for extramural research project grants, 7% for predoctoral and postdoctoral training, 6% for research management and support, 5% for the centers program in specialized areas, 5% for other research including career development, 2% for the intramural program, and 1% for contracts and other expenses (see NINR at http://www.ninr.nih.gov/). The NINR (2011) developed four strategies for building the science of nursing: “(1) integrating biological and behavior science for better health; (2) adopting, adapting, and generating new technologies for better health care; (3) improving methods for future scientific discoveries; and (4) developing scientists for today and tomorrow.” The areas of research emphasis include: (1) promoting health and preventing disease, (2) improving quality of life, (3) eliminating health disparities, and (4) setting directions for end-of-life research (NINR, 2011). Specific research priorities were identified for each of these four areas of research emphasis and were included in the NINR Strategic Plan. These research priorities provide important information for nurses seeking funding from the NINR. Details about the NINR mission, strategic plan, and areas of funding are available on its website at http://www.ninr.nih.gov/AboutNINR/NINRMissionandStrategicPlan/. Another federal agency that is funding healthcare research is the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The purpose of the AHRQ is to enhance the quality, appropriateness, and effectiveness of healthcare services, and access to such services, by establishing a broad base of scientific research and promoting improvements in clinical practice and in the organization, financing, and delivery of healthcare services. Some of the current AHRQ funding priorities are research focused on prevention; health information technology; patient safety; long-term care; pharmaceutical outcomes; system capacity and emergency preparedness; and the cost, organization, and socioeconomics of health care. For a complete list of funding opportunities and grant announcements, see the AHRQ website at http://www.ahrq.gov/. The World Health Organization (WHO) is encouraging the identification of priorities for a common nursing research agenda among countries. A quality healthcare delivery system and improved patient and family health have become global goals. By 2020, the world’s population is expected to increase by 94%, with the elderly population growing by almost 240%. Seven of every 10 deaths are expected to be caused by noncommunicable diseases, such as chronic conditions (heart disease, cancer, and depression) and injuries (unintentional and intentional). The priority areas for research identified by WHO are to (1) improve the health of the world’s most marginalized populations, (2) study new diseases that threaten public health around the world, (3) conduct comparative analyses of supply and demand of the health workforce of different countries, (4) analyze the feasibility, effectiveness, and quality of education and practice of nurses, (5) conduct research on healthcare delivery modes, and (6) examine the outcomes for healthcare agencies, providers, and patients around the world (WHO, 2012). A discussion of WHO’s mission, objectives, and research policies can be found online at http://www.who.int/rpc/en. The Healthy People 2020 website identifies and prioritizes health topics and objectives for all age groups over the next decade (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). These health topics and objectives direct future research in the areas of health promotion, illness prevention, illness management, and rehabilitation and can be accessed online at http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/default.aspx/.

Research Problem and Purpose

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

What Is a Research Problem and Purpose?

Sources of Research Problems

Clinical Practice

Researcher and Peer Interactions

Literature Review

Replication of Studies

Theory

Research Priorities

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access