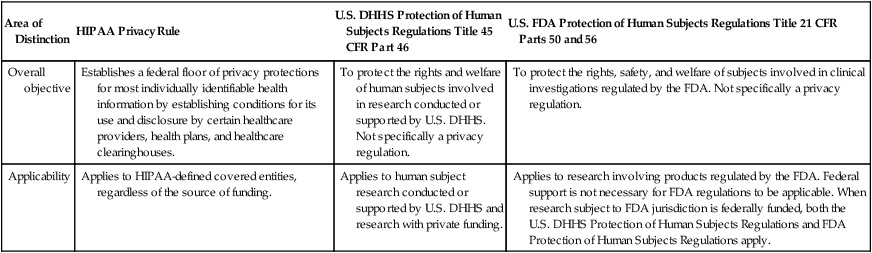

An ethical problem that has received increasing attention since the 1980s is research misconduct. Misconduct has occurred during the conduct, reporting, and publication of studies, and the Office of Research Integrity (ORI, 2012) was developed to manage this problem. Many disciplines, including nursing, have experienced episodes of research misconduct that have affected the quality of research evidence generated and disseminated. The ethical conduct of research has been a focus since the 1940s because of the mistreatment of human subjects in selected studies. Four experimental projects have been highly publicized for their unethical treatment of subjects: (1) Nazi medical experiments; (2) the Tuskegee syphilis study; (3) the Willowbrook study; and (4) the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital study. Although these were biomedical studies and the primary investigators were physicians, there is evidence that nurses were aware of the research, identified potential subjects, delivered treatments to the subjects, and served as data collectors in these projects. The four projects demonstrate the importance of ethical conduct for anyone reviewing, participating in, and conducting nursing or biomedical research. These four projects and other incidences of unethical treatment of subjects and research misconduct in the development, implementation, and reporting of research have influenced the formulation of ethical codes and regulations that direct research today. In addition, the concern for patient privacy with the electronic storage and exchange of health information has resulted in HIPAA privacy regulations (Olsen, 2003). From 1933 to 1945, the Third Reich in Europe implemented atrocious, unethical activities (Steinfels & Levine, 1976). The programs of the Nazi regime consisted of sterilization, euthanasia, and numerous medical experiments to produce a population of racially pure Germans, or Aryans, who the Nazis maintained were destined to rule the world. The Nazis encouraged population growth among the Aryans (“good Nazis”) and sterilized people they regarded as racial enemies, such as the Jews. They also practiced what they called “euthanasia,” which involved killing various groups of people whom they considered racially impure, such as the insane, deformed, and senile. In addition, researchers conducted numerous medical experiments on prisoners of war as well as on racially “valueless” persons who had been confined to concentration camps. The medical experiments involved exposing subjects to high altitudes, freezing temperatures, malaria, poisons, spotted fever (typhus), and untested drugs and operations, usually without any anesthesia (Steinfels & Levine, 1976). These medical experiments were conducted to generate knowledge about human beings, but the goal often was to destroy certain groups of people. Extensive examination of the records from some of these studies showed that they were poorly designed and conducted. Thus, they generated little if any useful scientific knowledge. The Nazi experiments violated numerous rights of the research participants. Researchers selected subjects on the basis of their race, demonstrating an unfair selection process. The subjects also had no opportunity to refuse participation; they were prisoners who were coerced or forced to participate. The study participants were frequently killed during the experiments or sustained permanent physical, mental, and social damage (Levine, 1986; Steinfels & Levine, 1976). The mistreatment of human subjects in these Nazi studies led to the development of the Nuremberg Code in 1949. The people involved in the Nazi experiments were brought to trial before the Nuremberg Tribunals, which publicized their unethical activities. These unethical studies resulted in the Nuremberg Code (1949), which was developed with guidelines for (1) subjects’ voluntary consent to participate in research; (2) the right of subjects to withdraw from studies; (3) protection of subjects from physical and mental suffering, injury, disability, and death during studies; and (4) the balance of benefits and risks in a study. Box 9-1 reproduces the Nuremberg Code, which was formulated mainly to direct the conduct of biomedical research worldwide; however, the rules it contains are essential to research in other sciences, such as nursing, psychology, and sociology. The Declaration of Helsinki includes ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects, such as the following: (1) well-being of the individual research subject must take precedence over all other interests; (2) a strong, independent justification must be documented prior to exposing healthy volunteers to risk of harm just to gain new scientific information; (3) investigators must protect the life, health, privacy, and dignity of research subjects; and (4) extreme care must be taken in making use of placebo-controlled trials, which should be used only in the absence of existing proven therapy (WMA General Assembly, 2008). Clinical trials must focus on improving diagnostic, therapeutic, and prophylactic procedures for patients with selected diseases without exposing subjects to any additional risk of serious or irreversible harm. Most institutions worldwide in which clinical research is conducted have adopted the Declaration of Helsinki. However, neither this document nor the Nuremberg Code has prevented some investigators from conducting unethical research (Beecher, 1966; ORI, 2012). In 1932, the U.S. Public Health Service (U.S. PHS) initiated a study of syphilis in black men in the small, rural town of Tuskegee, Alabama (Brandt, 1978; Rothman, 1982). The study, which continued for 40 years, was conducted to determine the natural course of syphilis in the adult black male. The research subjects were organized into two groups: one group consisted of 400 men who had untreated syphilis, and the other was a control group of 200 men without syphilis. Many of the subjects who consented to participate in the study were not informed about the purpose and procedures of the research. Some individuals were unaware that they were subjects in a study. By 1936, study results indicated that the men with syphilis experienced more health complications than the control group. Ten years later, the death rate of the group with syphilis was twice as high as that of the control group. The subjects were examined periodically but were not treated for syphilis, even after penicillin was determined to be an effective treatment for the disease in the 1940s (Brandt, 1978). Published reports of the Tuskegee syphilis study first started appearing in 1936, and additional papers were published every 4 to 6 years. In 1969, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reviewed the study and decided that it should continue. In 1972, a story describing the study published in the Washington Star sparked public outrage. Only then did the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (DHEW) stop the study. An investigation of the Tuskegee syphilis study found it to be ethically unjustified. From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, Dr. Saul Krugman at Willowbrook, an institution for the mentally retarded, conducted research on hepatitis (Rothman, 1982). The subjects, all children, were deliberately infected with the hepatitis virus. During the 20-year study, Willowbrook closed its doors to new inmates because of overcrowded conditions. However, the research ward continued to admit new inmates. To gain their child’s admission to the institution, parents were forced to give permission for the child to be a subject in the study. From the late 1950s to early 1970s, Krugman’s research team published several articles describing the study protocol and findings. Beecher (1966) cited the Willowbrook study as an example of unethical research. The investigators defended injecting the children with the virus by citing their own belief that most of the children would have acquired the infection after admission to the institution. The investigators also stressed the benefits that the subjects received, which were a cleaner environment, better supervision, and a higher nurse-patient ratio on the research ward (Rothman, 1982). Despite the controversy, this unethical study continued until the early 1970s. Another highly publicized example of unethical research was a study conducted at the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital in the 1960s. Its purpose was to determine the patients’ rejection responses to live cancer cells. Twenty-two patients were injected with a suspension containing live cancer cells that had been generated from human cancer tissue (Levine, 1986). An extensive investigation of this study revealed that the patients were not informed that they were taking part in research or that the injections they received were live cancer cells. In addition, the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital’s institutional review board never reviewed the study; even the physicians caring for the patients were unaware that the study was being conducted. The physician directing the research was an employee of the Sloan-Kettering Institute for Cancer Research, and there was no indication that this institution had reviewed the research project (Hershey & Miller, 1976). The study was considered unethical and was terminated, with the researcher being in violation of the Nuremberg Code (1949) and the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA General Assembly, 1964). This research had the potential to cause the study participants serious or irreversible harm and possibly death and reinforced the importance of conscientious institutional review and ethical researcher conduct. The continued conduct of harmful, unethical research made additional controls necessary. In 1973, the DHEW published its first set of regulations intended to protect human subjects. Clinical researchers were presented with strict regulations for research involving humans, with additional regulations to protect persons having limited capacities to consent, such as the ill, mentally impaired, and dying (Levine, 1986). All research involving human subjects had to undergo full institutional review, even nursing studies that involved minimal or no risks to study participants. Institutional review improved the protection of subjects’ rights; however, reviewing all studies, without regard for the degree of risk involved, overwhelmed the review process and greatly prolonged the time required for study approval. The government recognized the need for additional strategies to manage the problems related to the DHEW regulations. Because of the problems related to the DHEW regulations, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research (1978) was formed. The goals of the commission were (1) to identify the basic ethical principles that should underlie the conduct of biomedical and behavioral research involving human subjects and (2) to develop guidelines based on these principles. The commission developed The Belmont Report (available online at http://www.fda.gov/). This report identified three ethical principles as relevant to research involving human subjects: the principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. The principle of respect for persons holds that persons have the right to self-determination and the freedom to participate or not participate in research. The principle of beneficence requires the researcher to do good and “above all, do no harm.” The principle of justice holds that human subjects should be treated fairly. Currently, these ethical principles must be followed when researchers in the United States and internationally conduct studies. The commission developed ethical research guidelines based on these three principles, made recommendations to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (U.S. DHHS), and was dissolved in 1978. In response to the commission’s recommendations, the U.S. DHHS developed federal regulations in 1981 to protect human research subjects, which have been revised as needed over the last 30 years. The most current U.S. DHHS (2009) regulations are part of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 45, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects (available online at http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/policy/ohrpregulations.pdf/). These regulations are interpreted by the Office for Human Research Protection (OHRP), an agency within U.S. DHHS (2012), whose functions include: (1) providing guidance and clarification of regulations; (2) developing educational programs and materials; (3) maintaining regulatory oversight of research; and (4) providing advice on ethical and regulatory issues related to biomedical and social-behavior research. The U.S. DHHS (2009) regulations provide direction for (1) the protection of human subjects in research, with additional protection for pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, children, and prisoners; (2) the documentation of informed consent; and (3) the implementation of the institutional review board process. These regulations apply to all research involving human subjects in the following areas: (1) studies conducted, supported, or otherwise subject to regulations by any federal department or agency; (2) research conducted in educational and healthcare settings; (3) research involving the use of biophysical measures, educational tests, survey procedures, scales, interview procedures, or observation; and (4) research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens. Essentially all the biomedical and behavioral studies conducted in the United States are governed by the U.S. DHHS (2009) Protection of Human Subjects Regulations or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA). The FDA, within the U.S. DHHS, manages the CFR Title 21, Food and Drugs, Part 50, Protection of Human Subjects (U.S. FDA, 2010a), and Part 56, Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) (U.S. FDA, 2010b). These regulations apply to studies of drugs for humans, medical devices for human use, biological products for human use, human dietary supplements, and electronic products. The role of the FDA was expanded by the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act (FDAAA) of 2007 to include increased responsibility for the management of new drugs and medical devices. Physicians and nurses conducting clinical trials to generate new drugs and refine existing drug treatments must comply with these FDA regulations. In summary, these regulations focus on the protection of human subjects’ rights, informed consent (U.S, FDA, 2010a), and IRBs (U.S. FDA, 2010b), with content that is consistent with the U.S. DHHS (2009) regulations. The U.S. DHHS and FDA regulations provide guidelines to protect subjects in federally and privately funded research by ensuring privacy and confidentiality of information obtained through research. However, with the advent of electronic access and transfer, the public was concerned about the potential abuses of the health information of individuals in all circumstances, including research projects. Thus HIPAA was implemented in 2003 to protect an individual’s health information. The U.S. DHHS developed regulations titled the Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information, and compliance with these regulations is known as the Privacy Rule (U.S. DHHS, 2003). The HIPAA Privacy Rule established the category of protected health information (PHI), which allows covered entities, such as health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers that transmit health information, to use or disclose PHI to others only in certain situations. These situations are discussed later in this chapter. The HIPAA Privacy Rule affects not only the healthcare environment but also the research conducted in this environment (U.S. DHHS, 2010). An individual must provide his or her signed permission, or authorization, before his or her PHI can be used or disclosed for research purposes. To determine how the HIPAA Privacy Rule might impact the informed consent and IRB processes for your study, go to the website at http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/, which was developed to address researchers’ questions. Table 9-1 was developed to clarify the overall objectives and applicability of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations, and U.S. FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations (U.S. DHHS, 2007a). Any study you propose with human subjects must comply with these regulations. Thus, this chapter covers these regulations in the sections on protecting human rights, obtaining informed consent, and institutional review of research. TABLE 9-1 Clarification of the Focus of Federal Regulations and Impact on Research From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2007a). How do other privacy protections interact with the privacy rule? Retrieved from http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_05.asp/. Human rights are claims and demands that have been justified in the eyes of an individual or by the consensus of a group of individuals. Having rights is necessary for the self-respect, dignity, and health of an individual (Fry, Veatch, & Taylor, 2011). The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2001) Code of Ethics for Nurses and the American Psychological Association (APA, 2010) Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct provide guidelines for protecting the rights of human subjects in biological and behavioral research. Researchers and reviewers of research have an ethical responsibility to protect the rights of human research participants. The human rights that require protection in research are (1) the right to self-determination;, (2) the right to privacy; (3) the right to anonymity and confidentiality; (4) the right to fair treatment or justice; and (5) the right to protection from discomfort and harm (ANA, 2001; APA, 2010; Fry et al., 2011). The right to self-determination is based on the ethical principle of respect for persons. This principle holds that because humans are capable of self-determination, or controlling their own destinies, they should be treated as autonomous agents who have the freedom to conduct their lives as they choose without external controls. As a researcher, you treat prospective subjects as autonomous agents by informing them about a proposed study and allowing them to voluntarily choose to participate or not. In addition, subjects have the right to withdraw from a study at any time without a penalty (Fry et al., 2011). Conducting research ethically requires that research subjects’ right to self-determination not be violated and that persons with diminished autonomy have additional protection during the conduct of studies (U.S. DHHS, 2009). A subject’s right to self-determination can be violated through the use of (1) coercion; (2) covert data collection; and (3) deception. Coercion occurs when one person intentionally presents another with an overt threat of harm or the lure of excessive reward to obtain his or her compliance. Some subjects are coerced to participate in research because they fear that they will suffer harm or discomfort if they do not participate. For example, some patients believe that their medical or nursing care will be negatively affected if they do not agree to be research subjects. Sometimes students feel forced to participate in research to protect their grades or prevent negative relationships with the faculty conducting the research. Other subjects are coerced to participate in studies because they believe that they cannot refuse the excessive rewards offered, such as large sums of money, specialized health care, special privileges, and jobs. Most nursing studies do not offer excessive rewards to subjects for participating. Sometimes nursing studies have included a small financial reward of $10 to $30 or support for transportation to increase participation, but this would not be considered coercive (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Fry et al., 2011). An individual’s right to self-determination can also be violated if he or she becomes a research subject without realizing it. Some researchers have exposed persons to experimental treatments without their knowledge, a prime example being the Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital study. Most of the patients and their physicians were unaware of the study. The subjects were informed that they were receiving an injection of cells, but the word cancer was omitted (Beecher, 1966). With covert data collection, subjects are unaware that research data are being collected because the investigator develops a description of the study indicating that it is normal activity or part of health care (Reynolds, 1979). This type of data collection has more commonly been used by psychologists to describe human behavior in a variety of situations, but it has also been used by nursing and other disciplines (APA, 2010). Qualitative researchers have debated this issue, and some believe that certain group and individual behaviors are unobservable within the normal ethical range of research activities, such as the actions of cults or the aggressive or violent behaviors of individuals. Thus, these types of behaviors require study with covert data collection processes. However, covert data collection is considered unethical when research deals with sensitive aspects of an individual’s behavior, such as illegal conduct, sexual behavior, and drug use (U.S. DHHS, 2009). With the HIPAA Privacy Rule (U.S. DHHS, 2003), the use of any type of covert data collection would be questionable and illegal if PHI data were being used or disclosed. The use of deception in research can also violate a subject’s right to self-determination. Deception is the actual misinforming of subjects for research purposes (Kelman, 1967). A classic example of deception is the Milgram (1963) study, in which the subjects thought they were administering electric shocks to another person. The subjects were unaware that the person was really a professional actor who pretended to feel the shocks. Some subjects experienced severe mental tension, almost to the point of collapse, because of their participation in this study. The use of deception still occurs in some healthcare, social, and psychological investigations, but it is a controversial research activity. If deception is to be used in a study, researchers must determine that there is no other way to gain the essential research data needed and that the subjects will not be harmed. In addition, the subjects must be informed of the deception once the study is completed, provided full disclosure of the study activities that were conducted, (APA, 2010; Fry, 2011; U.S. DHHS, 2009) and given the opportunity to withdraw their data from the study. Some persons have diminished autonomy or are vulnerable and less advantaged because of legal or mental incompetence, terminal illness, or confinement to an institution (Fry et al., 2011). These persons require additional protection of their right to self-determination, because they have a decreased ability, or an inability, to give informed consent. In addition, these persons are vulnerable to coercion and deception. The U.S. DHHS (2009) has identified certain vulnerable groups of individuals, including pregnant women, human fetuses, neonates, children, mentally incompetent persons, and prisoners, who require additional protection in the conduct of research. Researchers need to justify their use of subjects with diminished autonomy in a study, and the need for justification increases as the subjects’ risk and vulnerability increase. However, in many situations, the knowledge needed to provide evidence-based care to these vulnerable populations can be gained only by studying them. Neonates and children (minors), the mentally impaired, and unconscious patients are legally or mentally incompetent to give informed consent. These individuals lack the ability to comprehend information about a study and to make decisions regarding participation in or withdrawal from the study. Their vulnerability ranges from minimal to absolute. The use of persons with diminished autonomy as research subjects is more acceptable if (1) the research is therapeutic, so that the subjects have the potential to benefit directly from the experimental process; (2) the researcher is willing to use both vulnerable and nonvulnerable individuals as subjects; (3) preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted and provide data for assessing potential risks to subjects; and (4) the risk is minimized and the consent process is strictly followed to secure the rights of the prospective subjects (U.S. DHHS, 2009). A neonate is defined as a newborn and is identified as either viable or nonviable on delivery. Viable neonates are able to survive after delivery, if given the benefit of available medical therapy, and can independently maintain a heartbeat and respiration. A nonviable neonate is a newborn who after delivery, although living, is not able to survive (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Neonates are extremely vulnerable and require extra protection to determine their involvement in research. However, research may involve viable neonates, neonates of uncertain viability, and nonviable neonates if the following five conditions are met: 1. The study is scientifically appropriate and the preclinical and clinical studies have been conducted and provided data for assessing the potential risks to the neonates. 2. The study provides important biomedical knowledge that cannot be obtained by other means and will not add risk to the neonate. 3. The research has the potential to enhance the probability of survival of the neonate. 4. Both parents are fully informed about the research during the consent process. 5. The research team will have no part in determining the viability of the neonate. In addition, for the nonviable neonate, the vital functions of the neonate should not be artificially maintained because of the research, and the research should not terminate the heartbeat or respiration of the neonate (U.S. DHHS, 2009). The unique vulnerability of children makes the decision to use them as research subjects particularly important. To safeguard their interests and protect them from harm, special ethical and regulatory considerations have been put in place for research involving children (U.S. DHHS, 2009). However, the laws defining the minor status of a child are statutory and vary from state to state. Often a child’s competency to consent is governed by age, with incompetence being nonrefutable up to age 7 years (Broome, 1999; Fry et al., 2011). Thus, a child younger than 7 years is not believed to be mature enough to assent or consent to research. Developmentally by age 7, a child is capable of concrete operations of thought and can give meaningful assent to participate as a subject in studies (Thompson, 1987). With advancing age and maturity, a child should have a stronger role in the consent process. To obtain informed consent, federal regulations require both the assent of the children (when capable) and the permission of their parents or guardians (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Assent means a child’s affirmative agreement to participate in research. Permission to participate in a study means the agreement of parents or guardian to the participation of their child or ward in research (U.S. DHHS, 2009). If a child does not assent to participate in the study, he or she should not be included as a subject even if parental permission is obtained. Using children as research subjects is also influenced by the therapeutic nature of the research and the risks versus the benefits. Thompson (1987) developed a guide for obtaining informed consent that is based on the child’s level of competence, the therapeutic nature of the research, and the risks versus the benefits (Table 9-2). Children who are experiencing a developmental delay, cognitive deficit, emotional disorder, or physical illness must be considered individually (Broome, 1999; Broome & Stieglitz, 1992). TABLE 9-2 HB, high benefit; LB, low benefit; MMR, more than minimal risk; MR, minimal risk. *A parent’s refusal can be superseded by the principle that a parent has no power to forbid the saving of a child’s life. †Children making “deliberate objection” would be precluded from participation by most researchers. ‡In cases not involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.” §In cases involving the privacy rights of a “mature minor.” From Thompson, P. J. (1987). Protection of the rights of children as subjects for research. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 2(6), 397. A child 7 years or older with normal cognitive development can provide assent or dissent to participation in a study, and the process for obtaining the assent should be included in the research proposal. In the assenting process, the child must be given developmentally appropriate information on the study purpose, expectations, and benefit-risk ratio (discussed later). DVDs, written materials, demonstrations, diagrams, role-modeling, and peer discussions are possible methods for communicating study information. The child also needs an opportunity to sign an assent form and to have a copy of this form. An example assent form is presented in Box 9-2. During the study, the researcher must give the child the opportunity to ask questions and to withdraw from the study if he or she desires (Broome, 1999). Assent becomes more complex if the child is bilingual, because the researchers must determine the most appropriate language to use for the consent process for the child and the parents. Holaday, Gonzales, and Mills (2007) offer a list of seven questions in their article to assist researchers in determining the language for communication during a study. Rew, Horner, and Fouladi (2010) conducted a study of school-aged children’s health behaviors to determine whether they were precursors of adolescents’ health-risk behaviors. The sample included Hispanic and non-Hispanic children and their parents. The ethical aspects of the study are described in the following quotation: Rew et al. (2010) provided a detailed description of the protection of the children and their parents’ rights. The study was described in a language of choice with an offer to answer questions. The parents agreed to their children’s participation in the study through signed permissions. The children gave written assent to participating in the study. Other ethical aspects of the study were the IRB approvals from the university and school administrators and the storage of study data in a secure location. All of these activities promoted the ethical conduct of this study according to the U.S. DHHS (2009) regulations. The researchers found that girls have more health-focused behaviors than boys, health behaviors decreased from grades 4 to 6, and the school environment was important for promoting health behaviors. Pregnant women require additional protection in research because of their fetuses. Federal regulations define pregnancy as encompassing the period of time from implantation until delivery. “A woman is assumed to be pregnant if she exhibits any of the pertinent presumptive signs of pregnancy, such as missed menses, until the results of a pregnancy test are negative or until delivery” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, 45 CFR Section 46.202). Research conducted with pregnant women should have the potential to directly benefit the woman or the fetus. If your investigation is thought to provide a direct benefit only to the fetus, you must obtain the consent of the pregnant woman and father. In addition, studies with pregnant women should include no inducements to terminate the pregnancy (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Certain adults have a diminished capacity for, or are incapable of, giving informed consent because of mental illness (Beebe & Smith, 2010), cognitive impairment, or a comatose state (Simpson, 2010). Persons are said to be incompetent if a qualified clinician judges them to have attributes that designate them as incompetent (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Incompetence can be temporary (e.g., inebriation), permanent (e.g., advanced senile dementia), or subjective or transitory (e.g., behavior or symptoms of psychosis). If an individual is judged incompetent and incapable of consent, you must seek approval from the prospective subject and his or her legally authorized representative. A legally authorized representative means an individual or other body authorized under law to consent on behalf of a prospective subject to his or her participation in research. However, individuals can be judged incompetent and can still assent to participate in certain minimal-risk research if they have the ability to understand what they are being asked to do, to make reasonably free choices, and to communicate their choices clearly and unambiguously (U.S. DHHS, 2009). A number of people in intensive care units and nursing homes are experiencing some level of cognitive impairment. These individuals must be assessed for their capacity to give consent to participate in research. The assessment needs to include the following elements: understanding of the study information, developing a belief about the information, reasoning ability, and understanding of a choice. Simpson (2010) reviewed the literature and found that the MacArthur Competency Assessment Tool for Clinical Research (MacCAT-CR) is one of the strongest instruments available for assessing an individual’s capacity to give informed consent. Using this instrument or others discussed by Simpson (2010), researchers can make a more sound decision about a subject’s ability to consent to research or about whether the legal guardian must be contacted for permission. Some individuals have become permanently incompetent from the advanced stages of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type (SDAT), and their legal guardians must give permission for their participation in research. Often families or guardians of these patients are reluctant to give consent for their participation in research. However, nursing research is needed to establish evidence-based interventions for comforting and caring for these individuals. Levine (1986) identified two approaches that families, guardians, researchers, or IRBs might use when making decisions on behalf of these incompetent individuals: (1) best interest standard and (2) substituted judgment standard. The best interest standard involves doing what is best for the individual on the basis of balancing risks and benefits. The substituted judgment standard is concerned with determining the course of action that incompetent individuals would take if they were capable of making a choice (Beattie, 2009). Jones, Munro, Grap, Kitten, and Edmond (2010) conducted a quasi-experimental study to determine the effect of toothbrushing on bacteremia risk in mechanically ventilated adults. These researchers described their process for obtaining consent from their study participants in the following study excerpt: Jones et al. (2010) developed a process for determining the cognitive competence of their potential research participants and obtained appropriate consent on the basis of their assessments. The competent subjects were given the right to self-determination regarding study participation. The researchers found that the toothbrushing intervention did not cause transient bacteremia in this population of ventilated patients. When conducting research on terminally ill subjects, you should determine (1) who will benefit from the research and (2) whether it is ethical to conduct research on individuals who might not benefit from the study (U.S. DHHS, 2009). Participating in research could have greater risks and minimal or no benefits for these subjects. In addition, the dying subject’s condition could affect the study results and lead you to misinterpret the results. However, Hinds, Burghen, and Pritchard (2007) stressed the importance of conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology to generate evidence that will improve the care for terminally ill children and adolescents. Some terminally ill individuals are willing subjects because they believe that participating in research is a way to contribute to society before they die. Others want to take part in research because they believe that the experimental process will benefit them. For example, individuals with AIDS might want to participate in AIDS research to gain access to experimental drugs and hospitalized care. Researchers studying populations with serious or terminal illnesses are faced with ethical dilemmas as they consider the rights of the subjects and their responsibilities in conducting quality research (Fry et al., 2011; U.S. DHHS, 2009). Hospitalized patients have diminished autonomy because they are ill and are confined in settings that are controlled by healthcare personnel (Levine, 1986). Some hospitalized patients feel obliged to be research subjects because they want to assist a particular practitioner (nurse or physician) with his or her research. Others feel coerced to participate because they fear that their care will be adversely affected if they refuse. Some of these hospitalized patients are survivors of trauma (such as auto accidents, gunshot wounds, or physical and sexual abuse) who are very vulnerable and often have decreased decision-making capacities (McClain, Laughon, Steeves, & Parker, 2007). When conducting research with these types of patients, you must pay careful attention to the informed consent process and make every effort to protect these subjects from feelings of coercion and harm (U.S. DHHS, 2009). In the past, prisoners have experienced diminished autonomy in research projects because of their confinement. They might feel coerced to participate in research because they fear harm if they refuse or because they desire the benefits of early release, special treatment, or monetary gain. Prisoners have been used for drug studies in which there were no health-related benefits and there was possible harm for the prisoners. Current regulations regarding research involving prisoners require that “the risks involved in the research are commensurate with risks that would be accepted by nonprisoner volunteers and procedures for the selection of subjects within the prison are fair to all prisoners and immune from arbitrary intervention by prison authorities or prisoners” (U.S. DHHS, 2009, Section 46.305). Protecting the rights of subjects with diminished autonomy in research is regulated internationally by the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). CIOMS (2010) developed international ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects, and the guidelines require protection of vulnerable individuals, groups, communities, and populations during research. Researchers must evaluate each prospective subject’s capacity for self-determination and must protect subjects with diminished autonomy during the research process (ANA, 2001, APA, 2010; U.S. DHHS, 2009). Privacy is an individual’s right to determine the time, extent, and general circumstances under which personal information will be shared with or withheld from others. This information consists of one’s attitudes, beliefs, behaviors, opinions, and records. The Privacy Act of 1974 provided the initial protection of an individual’s privacy. Because of this act, data collection methods were to be scrutinized to protect subjects’ privacy, and data cannot be gathered from subjects without their knowledge. Individuals also have the right to access their records and to prevent access by others (U.S. DHHS, 2009). The intent of this act was to prevent the invasion of privacy that occurs when private information is shared without an individual’s knowledge or against his or her will. Invading an individual’s privacy might cause loss of dignity, friendships, or employment or create feelings of anxiety, guilt, embarrassment, or shame. The HIPAA Privacy Rule expanded the protection of an individual’s privacy, specifically his or her protected individually identifiable health information, and described the ways in which covered entities can use or disclose this information. “Individually identifiable health information (IIHI) is information that is a subset of health information, including demographic information collected from an individual, and: (1) is created or received by healthcare provider, health plan, or healthcare clearinghouse; and (2) [is] related to past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition of an individual, the provision of health care to an individual, or the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to an individual, and that identifies the individual; or with respect to which there is a reasonable basis to believe that the information can be used to identify the individual” (U.S. DHHS, 2003, 45 CFR, Section 160.103). According to the HIPAA Privacy Rule, the IIHI is protected health information (PHI) that is transmitted by electronic media, maintained in electronic media, or transmitted or maintained in any other form or medium. Thus, the HIPAA privacy regulations affect nursing research in the following ways: (1) accessing data from a covered entity, such as reviewing a patient’s medical record in clinics or hospitals; (2) developing health information, such as the data developed when an intervention is implemented in a study to improve a subject’s health; and (3) disclosing data from a study to a colleague in another institution, such as sharing data from a study to facilitate development of an instrument or scale (Olsen, 2003). • The protected health information has been “de-identified” under the HIPAA Privacy Rule. (De-identifying PHI is defined in the following section.) • The data are part of a limited data set, and a data use agreement with the researcher(s) is in place. • The individual who is a potential subject for a study authorizes the researcher to use and disclose his or her PHI. • A waiver or alteration of the authorization requirement is obtained from an IRB or a privacy board (U.S. DHHS, 2007b) (see http://privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_08.asp/).

Ethics in Research

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Historical Events Affecting the Development of Ethical Codes and Regulations

Nazi Medical Experiments

Nuremberg Code

Declaration of Helsinki

Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Willowbrook Study

Jewish Chronic Disease Hospital Study

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Regulations

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research

Area of Distinction

HIPAA Privacy Rule

U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations Title 45 CFR Part 46

U.S. FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations Title 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56

Overall objective

Establishes a federal floor of privacy protections for most individually identifiable health information by establishing conditions for its use and disclosure by certain healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses.

To protect the rights and welfare of human subjects involved in research conducted or supported by U.S. DHHS. Not specifically a privacy regulation.

To protect the rights, safety, and welfare of subjects involved in clinical investigations regulated by the FDA. Not specifically a privacy regulation.

Applicability

Applies to HIPAA-defined covered entities, regardless of the source of funding.

Applies to human subject research conducted or supported by U.S. DHHS and research with private funding.

Applies to research involving products regulated by the FDA. Federal support is not necessary for FDA regulations to be applicable. When research subject to FDA jurisdiction is federally funded, both the U.S. DHHS Protection of Human Subjects Regulations and FDA Protection of Human Subjects Regulations apply.

Protection of Human Rights

Right to Self-Determination

Preventing Violation of Research Subjects’ Right to Self-Determination

Protecting Persons with Diminished Autonomy

Legally and Mentally Incompetent Subjects

Neonates

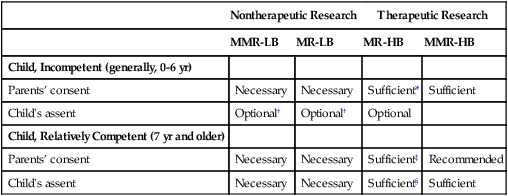

Children

Nontherapeutic Research

Therapeutic Research

MMR-LB

MR-LB

MR-HB

MMR-HB

Child, Incompetent (generally, 0-6 yr)

Parents’ consent

Necessary

Necessary

Sufficient*

Sufficient

Child’s assent

Optional†

Optional†

Optional

Child, Relatively Competent (7 yr and older)

Parents’ consent

Necessary

Necessary

Sufficient‡

Recommended

Child’s assent

Necessary

Necessary

Sufficient§

Sufficient

Pregnant Women

Adults with Diminished Capacity

Terminally Ill Subjects

Subjects Confined to Institutions

Right to Privacy

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Ethics in Research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access