Marcia Nusgart, RPh

Karen Ravitz, Esq

We’d like to thank Courtney Lyder, ND, GNP, FAAN, and Denise Richardson, EdD, for their contributions to the previous editions.

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- discuss the significance of the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- discuss reimbursement issues related to hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies

- identify quality improvement efforts

- describe essential wound documentation required for reimbursement.

Chapter Overview

Reimbursement regulations in wound care as in any other sector of health care can be quite complex. This chapter is organized into five major sections, which are as follows: role of regulations in health care, government payers in wound care, principles of wound care reimbursement, reimbursement of clinicians in different practice settings, and finally quality assessment and improvement issues.

Role of Regulation in Health Care

Regulations are a pervasive feature of the American healthcare system and, not surprisingly, significantly impact the delivery of wound care. Quite often, regulations and reimbursement determine who receives wound care and the level of wound care that’s delivered. Thus, if clinicians are to provide optimum care, it is essential for them to have knowledge about the regulations that impact wound care in their specific practice setting.

Although many clinicians may view the current regulatory environment as burdensome and unnecessary, it’s essential to recognize the important purpose that regulations fulfill. Quite simply, regulations are the mechanism through which government may promote its interest in the general welfare of society. Experience has demonstrated that government cannot rely solely on conventional market forces, such as the laws of supply and demand, to guide the use of resources to provide optimum care. These market forces, in the absence of the guiding hand of regulations, are often insufficient to ensure that healthcare resources are distributed equitably. In the case of wound care, the goal of current regulations is to ensure access to high-quality wound care, particularly for vulnerable populations such as the elderly and nursing home residents. Wound care regulations must be viewed from the perspective of how well they are achieving this goal.

At least four types of regulatory vehicles are available to the government to help achieve this goal. Government regulations may rely on subsidies or direct payments to providers; they may involve entry restrictions such as licensure and accreditations that seek to limit the ability to offer a particular service; they could use rate-setting or price-setting controls that determine reimbursements for care provided; or they could involve quality controls that seek to improve the care that is provided. Of these different potential mechanisms, the latter two are clearly the major regulatory vehicles used in wound care today and are the focus of this chapter. In this chapter, we describe the government payers in wound care and concentrate on the major regulatory agency involved in wound care in the United States—the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)—including an overview of how wound care is covered, coded, and reimbursed by CMS and its contractors; the different reimbursement scenarios depending on the clinicians’ practice settings; and a description of the agency’s efforts in improving the quality of wound care. Through these efforts, CMS aims to improve health and health care while also making care more affordable.

General Information on Government Payers in Wound Care

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

CMS is a federal agency within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Prior to July 1, 2001, it was called the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA). CMS administers the Medicare and Medicaid programs—two national healthcare programs that benefit about 75 million Americans. Moreover, because CMS provides the states with at least 50% of their finances for healthcare costs, the states must comply with federal regulations.

The difference is that while both the Medicare and Medicaid programs are administered through federal statutes that determine beneficiary requirements, what is covered, payment fees and schedules, and survey processes of clinical settings (such as skilled nursing facilities [SNFs] or home health agencies) are determined by their respective programs. Both programs have a wide variance on coverage, eligibility, and payment fees and schedules. Therefore, it’s important for the clinician to know what’s covered and the level of reimbursement prior to developing a treatment plan with the patient. Because CMS remains the largest health insurance agency, Medicaid as well as many private insurance companies will provide coverage at similar levels.

Medicare

The Medicare program was developed in 1965 by the federal government.1 In order to qualify for Medicare benefits, a person must be age 65 or older, have approved disabilities if under age 65, or have end-stage renal disease.

In 2013, Medicare provided coverage to 54 million people, spending $583 billion2 on benefits.3 These benefit payments are funded from two trust funds—the Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund and the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) trust fund. Most often these are referred to as Medicare Part A and Medicare Part B, respectively.4

The HI trust fund pays for a portion of the costs of inpatient hospital services and related care. Those services include critical access hospitals (small facilities that give limited outpatient and inpatient services to people in rural areas), SNFs, hospice care, and some home healthcare services. The HI trust fund is financed primarily through payroll taxes, plus a relatively small amount of interest, income taxes on Social Security benefits, and other revenues.

The SMI trust fund pays for a portion of the costs of physicians’ services, outpatient hospital services, and other related medical and health services. As of 2014, the premium for Medicare Part B is $104.90 per month. This premium will not change in 2015. In some cases, this amount may be higher if the person doesn’t choose Medicare Part B when he or she first becomes eligible at age 65 or if the person files taxes greater than $85,000 as an individual or $170,001 as part of a couple. In addition, as of January 2006, the SMI trust fund pays for private prescription drug insurance plans to provide drug coverage under Part D of the program. The separate Part B and Part D accounts in the SMI trust fund are financed through general revenues, beneficiary premiums, interest income, and, in the case of Part D, special payments from the States.

The Medicare+Choice program was authorized by the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.5 In this program, beneficiaries have the traditional Medicare Part A and Part B benefits, but they may also select Medicare managed care plans (such as health maintenance organizations [HMOs], preferred provider organizations [PPOs], or private fee-for-service plans). Medicare+Choice plans provide care under contract to Medicare. They may provide benefits such as coordination of care or reducing out-of-pocket expenses. Some plans may also offer additional benefits, such as prescription drugs.

Prescription drug benefits are available for all Medicare beneficiaries regardless of income, health status, or prescription drug use6 through Medicare Part D. A range of plans are available, so beneficiaries have multiple options for coverage. Moreover, persons can add drug coverage to the traditional Medicare plan through a “stand-alone” prescription drug plan or through a Medicare Advantage plan, which includes an HMO or PPO and typically provides more benefits at a significantly lower cost through a network of doctors and hospitals. Presently, no wound care products are covered under this benefit.

Patient Teaching

Patient Teaching

Explain to the patient and family that wound care products are not covered under Medicare Part D.

Medicaid

The Medicaid program was developed in 1965 as a jointly funded cooperative venture between the federal and state governments to assist states in the provision of adequate medical care to eligible people.1 Medicaid is the largest program providing medical and health-related services to America’s poorest people. Within broad national guidelines provided by the federal government, each of the states:

- administers its own program

- determines the type, amount, duration, and scope of services

- establishes its own eligibility standards

- sets the rate of payment for services

- determines what products are covered in that state.

Thus, the Medicaid program varies considerably from state to state as well as within each state over time. This wide variance also affects what’s covered in wound care. For example, the number of times debridement of a wound is reimbursed differs by state, as do product treatment options.

Managed Care Organizations

Manage Care Organizations (MCOs) were developed to provide health services while controlling costs. They combine the responsibility for paying for a defined set of health services with an active program to control the costs associated with providing those services, while at the same time attempting to control the quality of and access to those services. The health benefits, which usually range from acute care services to dental and vision coverage, are usually clearly identified, as are the payment, co-payment, and deductibles that are required for a specific health procedure (e.g., compression therapy for chronic venous insufficiency ulcer). Moreover, the MCO usually receives a fixed sum of money to pay for the benefits in the plans for the defined population of enrollees. Typically, this fixed sum is constructed through premiums paid by the enrollees, capitation payments made on behalf of the enrollees from a third party, or both. There are wide variations in MCOs and the services they provide for patients with wounds.

General Wound Care Reimbursement Principles

Reimbursement directly impacts how clinicians deliver care. Increasingly, third-party payer sources (Medicare, Medicaid, HMOs) are examining where their money is going and whether they’re getting the most from providers on behalf of their beneficiaries. Thus, third-party payers are requiring more documentation regarding patient outcomes to justify payment. Clinicians who can document comprehensive and accurate assessments of wounds and the outcomes of their interventions are in a stronger position to obtain and maintain coverage and thus reimbursement.

Evidence-based wound care should always be the goal of clinicians. However, clinicians are increasingly being challenged to provide optimum wound care based on healthcare setting and third-party payers.

Medicare reimbursement is more than just the payment for medical items and services. The key to understanding how Medicare reimburses providers, physicians and suppliers for wound care involves a greater understanding of three main components that comprise the Medicare reimbursement system: Coding, Coverage, and Payment. Each is a separate and distinct process. Just because a product is awarded a code does not mean it will be covered. Just because it is awarded a code and covered does not mean it will be reimbursed. Similarly, all procedures performed by clinicians have codes assigned to them and are reimbursed based on the payment system for the setting in which it was performed.

Since coding and coverage are universal to all settings, they will be discussed first. Then we will discuss reimbursement in a setting-specific fashion.

Coding

In order for medical claims to be processed, billing codes are used by physicians, hospitals and other providers to identify the diagnosis, product, service and procedure that the clinician used in treating the patient in which they are billing a payer. Accurate coding is necessary in order for the claim to be properly and accurately processed.

The types of codes that are used include:

- Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) Level I and Level II

- Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG)

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and soon to be released ICD-10)

HCPCS Level I

HCPCS Level I or Common Procedural Terminology (CPT®) codes are numbers assigned to a procedure that a clinician (e.g., physician, nurse practitioner, podiatrist) may perform on a patient, including medical, surgical, and diagnostic services. The codes are then used by insurers (Medicare, Medicaid, and private payers) to determine the amount of reimbursement for the clinician. Every clinician uses the same codes to ensure uniformity, but the amount of reimbursement may differ depending on the type of clinical professional. An example of a CPT code for wound care is CPT 11042—debridement of subcutaneous tissue, first 20 cm2 or less.

HCPCS Level II

HCPCS Level II code set is made up of five-character alphanumeric codes representing primarily medical supplies, durable medical goods, nonphysician services, and services not represented in the Level I code set (CPT). HCPCS Level II includes services such as ambulance, durable medical equipment, prosthetics, orthotics, and supplies (DMEPOS) when used outside a physician’s office. Cellular and/or Tissue Based Products for Wounds (CTPs), an updated and more clinically appropriate term for “skin substitutes”; surgical dressings; support surfaces; and negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) all have HCPCS Level II codes.

Diagnosis-Related Group

DRG is used for inpatient hospital claims. DRGs are a means of classifying a patient under a particular group where those assigned are likely to need a similar level of hospital resources for their care. This allows hospital administrators to more accurately determine the type of resources needed to treat a particular group and to predict more closely the cost of that treatment.

International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9 and Soon to be Released ICD-10)

ICD-9 International classification of diseases (soon to be ICD-10) is a set of codes used by physicians, hospitals, and allied health workers to indicate diagnosis for all patient encounters. The ICD-9-CM coding system contains about 16,000 diagnosis codes and ICD-10-CM contains over 68,000 codes. Currently the ICD-10 release has been delayed in the United States.

Coverage

Coverage is the existence of a medical benefit category for a service, procedure, device, drug or supply used in healthcare delivery. Coverage varies by the type of health plan (i.e., Medicare, Medicaid, private pay, etc.), the setting of care (i.e., hospital, home health, SNF, physician office, etc.), and the condition of the patient. If coverage is permissible, payers may have a separate coverage policy that will dictate the specific criteria in which they will permit coverage of that product, service, or procedure. The coverage policy will set forth medical conditions, diagnosis, coding, and specific requirements and/or limitations for coverage of that particular service or product.

The different settings by which coverage may be permitted for wound care includes hospitals (inpatient, outpatient, and long-term care hospitals), outpatient clinics—including wound care clinics, SNFs, and physician offices and also home care.

In the Medicare program, there is no national coverage policy for most of the products that would be used to treat a patient with a chronic wound. Rather, coverage for most wound care products are made through local coverage determinations (LCDs) by the Part A and B Medicare Administrative Contractors (AB MACs) for CTPs and the Durable Medical Equipment Medicare Administrative Contractors (DMEMACs) for surgical dressings, NPWT and support surfaces. The only product provided to wound care patients in which there is a national coverage decision issued by CMS is hyperbaric oxygen treatment.

The following is additional information regarding the CMS contractors who create and implement the LCDs—the DMEMACs and the A/B MACs

Durable Medical Equipment Medicare Administrative Contractors

Implementation of the Medicare program (for instance, eligibility requirements and payments) in home care is handled by numerous insurance companies that are subcontracted by CMS. In 1993, CMS contracted four carriers to process claims for DMEPOS under Medicare Part B.7 CMS divided the country into four regions, with each region having its own DME regional carrier. The HCPCS, an alphanumeric system used to identify coding categories not included in the American Medical Association’s CPT-4 codes, is usually used with DMEPOS.8

In January 2006, CMS eliminated fiscal intermediaries who processed Medicare claims (Medicare Part A only) and carriers (Medicare Part B only),9 eliminated the DME regional carriers, and awarded four specialty contractors through a competitive bidding process. The new DME Medicare administrative contractors (DME MACs) are responsible for handling the administration of Medicare claims from DMEPOS suppliers. The benefit of the new system is a more streamlined process between the beneficiary and the supplier. The DME MACs serve as the point of contact for all Medicare suppliers, whereas beneficiaries can register their claims-related questions to Beneficiary Contact Centers (Table 2-1).

Table 2-1 The Four Durable Medical Equipment Medicare Administrative Contractors

DME MACs clearly define local medical coverage policies. The beneficiary usually pays the first $100.00 for covered medical services annually. Once that has been met, the beneficiary pays 20% of the Medicare-approved amount for services or supplies. If services weren’t provided on assignment, then the beneficiary pays for more of the Medicare coinsurance plus certain charges above the Medicare-approved amount.

Medicare Part B provides coverage for NPWT pumps. In order for an NPWT pump and supplies to be covered, the patient must have a chronic stage III or IV pressure ulcer, neuropathic ulcer, venous or arterial insufficiency ulcer, or a chronic (at least 30 days) ulcer of mixed etiology. Extensive documentation is required prior to a DME MAC approving coverage for NPWT. Thus, it is important for the clinician to review the coverage policy to ensure that the product is covered under the Medicare program.10

Support surfaces are also covered under Medicare Part B.10–12 CMS has divided support surfaces into three categories for reimbursement purposes:

- Group 1 devices are those support surfaces that are static and don’t require electricity. Static devices include air, foam (convoluted and solid), gel, and water overlay or mattresses.

- Group 2 devices are powered by electricity or pump and are considered dynamic in nature. These devices include alternating and low-air-loss mattresses.

- Group 3 devices are also considered dynamic in nature. This classification comprises only air-fluidized beds.

Specific criteria must be met before Medicare will reimburse for support surfaces; therefore, it is essential for the clinician to review the policy.

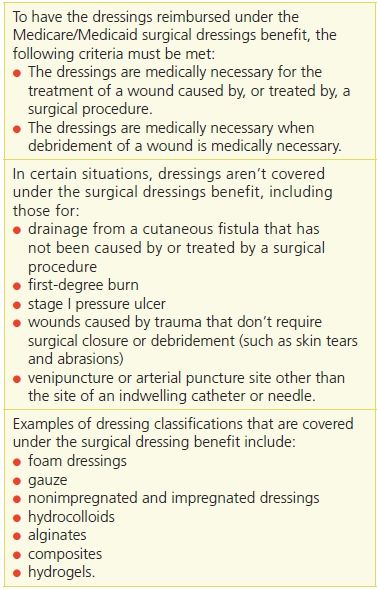

The surgical dressings benefit covers primary and secondary dressings in outpatient acute care clinic settings (e.g., a hospital outpatient wound center) and physician offices (Table 2-2).13 This coverage policy is determined by the DMEMACs as well.

Table 2-2 Coverage Under the Surgical Dressings Benefit

A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors

A/B Medicare Administrative Contractors, or A/B MACs, are private organizations that carry out the administrative responsibilities of traditional Medicare for Part A and B. They are responsible for claims processing, or cutting checks to Medicare providers for their services; ensuring services are correctly coded and billed for, both before and after payment; deciding which healthcare services are medically necessary, and collecting overpayments. MACs follow the national coverage determinations set by the CMS, but in cases where there is no such determination or the rules are too vague regarding a specific procedure, an MAC may develop a LCD. The coverage polices for cellular and/or tissue products for wound (CTPs) are administered through these A/B MAC contractors in their local jurisdictions within LCDs. In these policies, the coverage parameters can vary from one jurisdiction to another as can the title of the policy itself. The clinician would need to refer to each of the jurisdictions in order to understand whether CTPs are covered in their jurisdiction and what are the parameters for coverage. There are currently 10 jurisdictions (Table 2-3).

Table 2-3 The 10 AB Medicare Administrative Contractors

Payment

Payment refers to the methodology used to determine reimbursement to a healthcare provider or supplier. Payment may take the form of a global or bundled payment for the combination of services needed to treat a particular condition, as is the case with many hospital inpatient and outpatient discharges, or may be made on an itemized basis, as is the case for many physician services such as office visits. In many cases, the payment method will be determined by the site of service rather than by the item or service itself.

As mentioned above, since wound care is provided in multiple settings, a later section on “How Reimbursement Works in Clinicians’ Practice Settings” is devoted to the various healthcare settings and how wound care products and services are reimbursed by CMS.

Correct Documentation Is Key for Payment

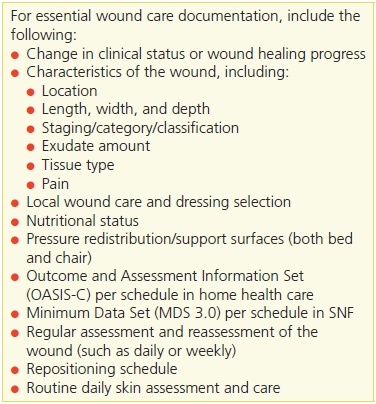

Comprehensive documentation is the critical foundation for successful reimbursement of services and products. Physician documentation of pressure ulcers at the time of hospitalization is particularly important for identifying present on admission (POA) status. Regulatory agencies, independent of healthcare setting, set forth the requisite documentation for reimbursement, and their requirements for documentation should always be carefully reviewed prior to applying for coverage. Thorough documentation justifies the medical necessity of services and products and should reflect the care required in the prevention or treatment of wounds. In order to promote better documentation as well as the availability of data necessary for quality measurement, CMS is also promoting the “meaningful use” of electronic health records.14 Specific financial incentives are available to providers using electronic health records and reporting data on quality of care (Table 2-4).

Table 2-4 Essential Wound Documentation

How Reimbursement Works in Clinicians’ Practice Settings

Hospital Inpatient

Hospital reimbursement is part of the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS). Payments made under the IPPS totaled $120 billion and accounted for about 25% of Medicare spending in 2012.15 The inpatient benefit covers beneficiaries for 90 days of care per episode of illness. There is a 60-day lifetime reserve. The episode of care begins when the Medicare beneficiary is admitted to the hospital and ends when he or she has been out of the hospital or an SNF for 60 consecutive days.15

Under the IPPS, the ICD-9, or soon to be ICD-10 CM, is used to track to an MS-DRG. Hospitals are reimbursed on a predetermined, lump-sum fixed rate for each MS-DRG. The payment amount for a particular service is derived based on the classification system of that service. For hospitals, this payment would also include all medical care, procedures, and surgeries, wound care products, devices, and support surfaces. Because the IPPS is based on an adjusted average payment rate, some cases will receive payments in excess of cost (less than the billed charges), whereas others will receive payment that’s less than cost.16 The system is designed to give hospitals the incentive to manage operations more efficiently by evaluating those areas in which increased efficiencies can be instituted without affecting the quality of care and by treating a mix of patients to balance cost and payments.

CMS does review the MS-DRGs annually to ensure that each grouping continues to be grouped correctly with clinically similar conditions requiring similar resources. If their review concludes that clinically similar cases within an MS-DRG use significantly different amounts of resources, CMS will reassign them to different MS-DRGs or create a new MS-DRG. There are currently approximately 500 groups.

Rehabilitation hospitals and units and long-term care facilities (defined as those with an average length of stay of at least 25 days) are excluded from the PPS. Instead, they’re paid on a reasonable-cost basis, subject to per-discharge limits.16 They are also paid depending on hospital-specific contracts and different payer sources. Note that CMS doesn’t recognize subacute status; rather, subacute facilities are governed by the SNF regulations.

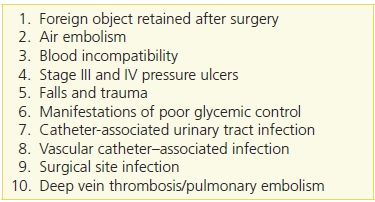

The Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005 was passed in February 2006 in an effort to limit payments to hospitals for conditions resulting from potentially poor quality of care.17 Section 5001(c) of the DRA requires the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services or a designee to identify conditions that (1) are high cost, high volume, or both; (2) result in the assignment of a case to a DRG that has a higher payment when present as a secondary diagnosis; and (3) could reasonably have been prevented through the application of evidence-based guidelines. Section 5001(c) provides that CMS can revise the list of conditions from time to time, as long as it contains at least two conditions.

Stage 3 and 4 pressure ulcers and surgical site infections were identified as two of the initial hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) that met the DRA (Table 2-5). Thus, if clinicians do not identify and subsequently document the pressure ulcer(s) or specific surgical site infection as POA, then the hospital will not be permitted to claim payment either as a primary or secondary diagnosis. The POA Indicator requirement and HAC payment provision only apply to inpatient PPS hospitals. At this time, a number of hospitals are exempt from the POA Indicator and HAC payment provisions, including critical access hospitals, long-term care hospitals, cancer hospitals, children’s inpatient facilities, and rural health clinics.

Table 2-5 The 10 Categories of Hospital-Acquired Conditions

The DRA also directed CMS to develop and standardize patient assessment information from acute and post–acute care settings. This resulted in the development of the Continuity Assessment Record and Evaluation (CARE) Tool. The CARE Tool measures the health and functional status of Medicare acute discharges as well as changes in severity and other outcomes for Medicare post–acute care patients while controlling for factors that affect outcomes, such as cognitive impairments and social and environmental factors. Many of the items are already collected in hospitals, SNFs, or home care settings, although the exact item form may be different. The tool is designed to eventually replace similar items on the existing Medicare assessment forms, including the Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS), Minimum Data Set (MDS), Resident Assessment Protocol (RAP), and Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility–Patient Assessment Instrument (IRF-PAI) tools. (See Chapter 6, Wound Assessment, for more information about the CARE Tool.)

It is anticipated that use of the CARE Tool will help improve the quality of care transitions, leading to a reduction in inappropriate hospital readmissions. Four major domains are included in the tool: medical, functional, and cognitive impairments and social/environmental factors. These domains were chosen either to measure case mix severity differences within medical conditions or to predict outcomes such as discharge to home or community, rehospitalization, and changes in functional or medical status. Section G covers skin integrity and is used to assess pressure ulcers, delayed healing of surgical wounds, trauma-related wounds, diabetic foot ulcers, vascular ulcers (arterial and venous), and other wounds (e.g., incontinence-associated dermatitis).18,19

Hospital Outpatient Centers

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 provided authority for CMS to develop a PPS under Medicare for hospital outpatient services. The new outpatient PPS took effect in August 2000.20 All services paid under this PPS are placed into ambulatory payment classifications (APCs). A payment rate is established for each APC, depending on the services/procedures provided. CPT codes and modifiers identify clinic visits and services/procedures. The CPT codes track to an APC group based on the cost and the level of resources required to perform the service or procedure. Services or procedures in each APC are similar in cost. Since hospital outpatient claims are submitted to the Part B Medicare Administrative Contractor, the MAC pays a predetermined amount for the APC group—which includes all supplies including, but not limited to, wound care dressings. Beginning in 2013, CMS determined that cellular- and tissue-based products for wounds should be bundled. As a result, these products are now packaged into the facility fee for the procedure.

Hospitals may be paid for more than one APC per encounter. Medicare beneficiaries also can pay a coinsurance, which is the amount they will have to pay for services furnished in the hospital outpatient department after they have met the Medicare Part B deductible. A coinsurance amount is initially calculated for each APC based on 20% of the national median charge for services in the APCs. The coinsurance amount for an APC doesn’t change until the amount becomes 20% of the total APC payment. It should be noted that the total APC payment and the portion paid as coinsurance amounts are adjusted to reflect geographic wage variations using the hospital wage index and assuming that the portion of the payment/coinsurance that’s attributable to labor is 60%.

Skilled Nursing Facilities

A patient who is eligible for Medicare may receive Medicare Part A for up to 100 days per benefit period in an SNF.21 The patient must satisfy specific rules in order to qualify for this benefit. These rules include the following:

- Beneficiary is admitted to SNF or to the SNF level of care in a swing-bed hospital within 30 days after the date of hospital discharge.

- Beneficiary must have been in a hospital receiving inpatient hospital services for at least 3 consecutive days (counting the day of admission but not the day of discharge).

- Beneficiary requires skilled nursing care by or under the supervision of a registered nurse or requires physical, occupational, or speech therapy that can only be provided in an inpatient setting.

- Services are needed on a daily basis.

- Skilled services are required for the same or related health problem that resulted in the hospitalization.

After the SNF accepts a patient with Medicare Part A, all routine, ancillary, and capital-related costs are covered in the PPS. Thus, wound care supplies, therapies, and support surfaces are included in the PPS per diem rate. The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 modified how payments were made for Medicare SNF services.21 After July 1, 1998, SNFs were no longer paid on a reasonable cost basis or through low volume prospectively determined rates but rather on the basis of a PPS. The PPS payment rates are adjusted for case mix and geographic variation (urban vs. rural) in wages. The PPS also covers all costs of furnishing covered SNF services. The SNF isn’t permitted to bill under Medicare Part B until the 100 days are in effect.22

All SNFs participating in Medicare and Medicaid must also comply with federal and state regulations. In November 2004, CMS released its revised interpretative guidance on pressure ulcers (Federal Tag 314).23 F-314 is a federal regulation that states that a resident entering a long-term care facility will not get a pressure ulcer or if they have a pressure ulcer it will not worsen. This 40-page document is used by both federal and state surveyors to determine the SNF compliance with F-314. It also provides SNFs with evidence-based approaches to prevent and treat pressure ulcers. SNFs that are found to be noncompliant with the pressure ulcer regulation can receive civil money penalties, which currently range from $500 to $10,000 per day, or CMS and the state can withhold payments and close the facility because of system-wide imminent danger to residents. Additional skin or wound regulations include F-309, in which SNFs can be cited for all other ulcers besides pressure ulcers, and F-315, which addresses the need to protect the skin from the effects of urinary incontinence.

Resident Assessment Instrument

In order to meet its regulatory role, CMS requires that a Resident Assessment Instrument (RAI) be completed on all SNF residents. The RAI included the MDS 2.0 RAPs and utilization guidelines that have been in use since 1995. The MDS is a 400-item assessment form that attempts to identify the functional capacity of residents in SNFs. Based on the MDS section, further assessments are triggered by RAPs, which assess common clinical problems found in SNFs, such as pressure ulcers and urinary incontinence. RAPs also have utilization guidelines that assist the healthcare team in planning the overall care of the resident. The comprehensive RAI is completed annually, with quarterly MDS assessments (less comprehensive) completed between the annual assessments. The SNF is required to do another RAI if the resident’s health status changes significantly. Only pressure and stasis ulcers are clearly delineated on the MDS 2.0 version; all other ulcers are grouped in the “other” category. Section M of the MDS assesses ulcers by stage, type of ulcer (pressure or stasis), other skin lesions present, skin treatments, and foot problems.24

CMS has been using the new MDS version 3.0 since October 1, 2010.25 This revised version is intended to improve reliability, accuracy, and usefulness; to include the resident in the assessment process; and to use standard protocols used in other settings. These improvements have profound implications for enhanced accuracy, which supports the primary legislative intent that the MDS be a tool to improve clinical assessment. The CMS has adapted the National Pressure Ulcer Assessment Panel’s 2007 definition of a pressure ulcer as well as the staging categories of pressure ulcers. One of the new areas in section M (skin) has eliminated the confusion that requires staging of all chronic ulcers.26,27 Staging of pressure ulcers will involve simply staging the deepest tissue involved and worsening pressure ulcers. Another major change has been the delineation between unstageable pressure ulcers and suspected deep tissue injury.

The RAI is a very useful instrument in planning the care of SNF residents. The RAI User’s Manual Version 3.0 no longer uses RAPs to connect MDS data to care planning. Instead of RAPs, there are care area triggers (CATs) and care area assessments (CAAs). MDS 3.0 is tied to care planning first through the CAT grid, which triggers each CAA. Like the prior version, the MDS is only a preliminary screen that will identify potential issues that the interdisciplinary team will further explore. The interdisciplinary team should identify current clinical protocols and resources to guide the CAA, and these resources should be identifiable on request by surveyors.26

The CAA is therefore designed to expand the assessment process that begins with the MDS. One area that is beneficial from this expanded assessment is whether the ulcer was avoidable or unavoidable. MDS 3.0 section M does not address unavoidability, but this is an important issue that most if not all facilities would like to incorporate. The CAA allows the interdisciplinary team to identify specific guidelines that can be incorporated into the assessment and care planning process. Because the issue of unavoidability may depend on the presence of multiple comorbidities and physiological disturbances, collaboration with the physician will be an important component of this extended assessment.26

CAAs triggered by CATs in section M include pressure ulcers, nutritional status, and dehydration/fluid maintenance. The CAA for pressure ulcers is automatically triggered by any resident considered to be at risk, any stage of pressure ulcer, or any worsening ulcer. The net result of these changes is closer linkage of the resident assessment to quality of life, incorporation of updated guidelines for ulcer staging, and broadening of the care planning process to include current clinical protocols and evidence-based standards.26

Resource Utilization Groups

The RAI is also linked to payment.28 All Medicare Part A payments are linked to the RAI, and, in some states, Medicaid payments are based solely on completion of the MDS. Based on the MDS, each resident is assigned to one of 66 resource utilization groups (RUGs). RUGs are clusters of nursing home residents based on resident characteristics that explain resource use.29 The classification system includes 14 rehabilitation groups, 9 groups for days with rehabilitation and extensive services, 3 groups for extensive services, 16 groups for special care, and 10 groups for clinically complex care. Wound care is typically within the special care group.

RUG rates are computed separately for urban and rural areas, and a portion of the total rate is adjusted to reflect labor market conditions in each SNF’s location. The daily rate for each RUG is calculated using the sum of three components:

- a fixed amount for routine services (such as room and board, linens, and administrative services)

- a variable amount for the expected intensity of therapy services

- a variable amount reflecting the intensity of nursing care that patients are expected to require.

Because of RUGs, it’s essential for the SNF to complete the MDS correctly. The SNF must pay close attention to all health problems of the resident because the more intensive the care required, the higher the daily rate will be. Moreover, completing the MDS accurately and in a timely manner will help to ensure correct payments. If an SNF doesn’t complete the MDS in a timely manner, it receives a default payment, which is usually significantly lower, or it may not receive payment at all. An SNF is required to evaluate each patient on the 5th, 14th, 30th, 60th, and 90th day.

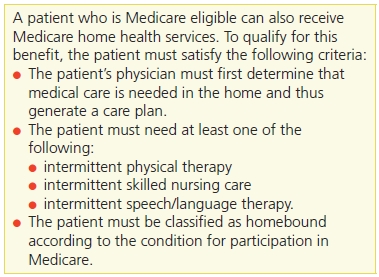

Home Health Agencies

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 also called for the development and implementation of a PPS for Medicare home health services. On October 1, 2000, home health PPS was implemented30 (Table 2-6). Beneficiaries receiving home health care are typically restricted to their homes, need skilled care on a part-time or intermittent basis, and are not required to make any co-payments for these services.

Table 2-6 Qualifying for Home Health Benefits

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree