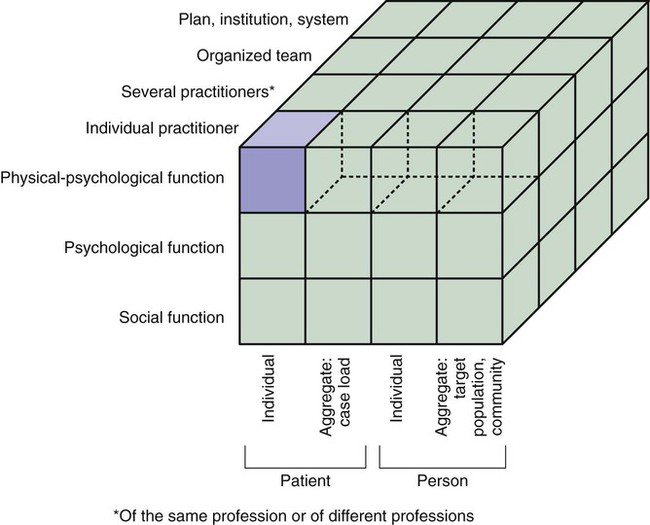

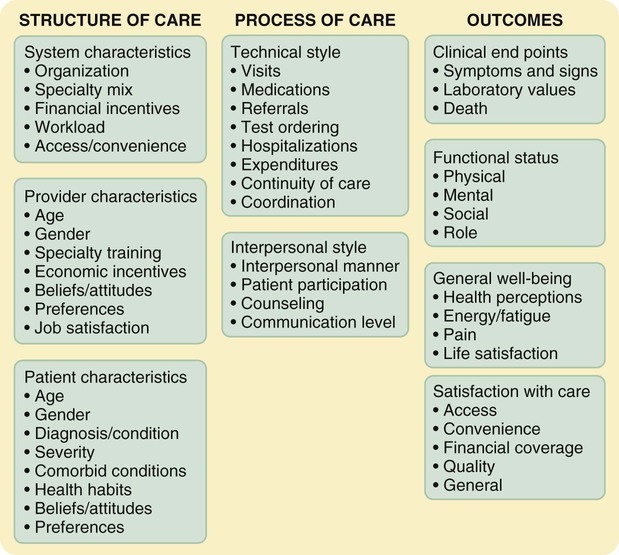

Outcomes research, now an established field of health research, focuses on the end results of patient care. Numerous studies have been conducted by nursing and medicine over the last three decades in the United States (Aiken, Clarke, Sloane, Lake, & Cheney, 2008; Bakker et al., 2011; Stone et al., 2007), Canada (Tourangeau, 2003; Tourangeau et al., 2007), and internationally (Van den Heede et al., 2009) that explore the relationships among nursing interventions and patient outcomes. Nursing-related interventions and variables that have been studied include skill mix and configuration of nursing personnel; staffing levels; assignment patterns (primary, functional, or team); shift patterns; levels of nursing education, experience, and expertise; ratios of full-time to part-time nurses; level and type of nursing leadership available centrally and on units; cohesion and communication among the nursing staff and between nurses and physicians; the implementation of clinical care maps for patients with selected diagnoses; and the interrelationships of these factors. The theory on which outcomes research is based emerged from evaluation research (Structure-Process-Outcomes Framework). The theorist Avedis Donabedian (1976, 1978, 1980, 1982, 2005) proposed a theory of quality health care and the process of evaluating it. Quality is the overriding construct of the theory; however, Donabedian never defined this concept himself (Mark, 1995). He noted that quality of care is a “remarkably difficult notion to define and is a reflection of the values and goals current in the medical care system and in the larger society of which it is a part” (Donabedian, 2005, p. 692). The World Health Organization (2009, p. 13) defined quality of care as the “degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.” The cube shown in Figure 13-1 explains the elements of quality health care. The three dimensions of the cube are health, subjects of care, and providers of care. The concept health has many aspects; three are shown on the cube: physical-physiological function, psychological function, and social function. Donabedian (1987, p. 4) proposed that “the manner in which we conceive of health and of our responsibility for it, makes a fundamental difference to the concept of quality and, as a result, to the methods that we use to assess and assure the quality of care.” The concept providers of care shows levels of aggregation and organization of providers. The first level is the individual practitioner. At this level, consideration is given to the individual provider rather than others who might be involved in the subject’s care, whether individual or aggregate. As the levels progress, providers of care include several practitioners, who might be of the same profession or different professions and “who may be providing care concurrently, as individuals, or jointly, as a team” (Donabedian, 1987, p. 5). At higher levels of aggregation, the provider of care is institutions, programs, or the healthcare system as a whole. Donabedian theorized that the dimensions of health are defined by the subjects of care, not by the providers of care, and are based on “what consumers expect, want, or are willing to accept” (Donabedian, 1987, p. 5). Thus, practitioners cannot unilaterally enlarge the definition of health to include other aspects; this action requires social consensus that “the scope of professional competence and responsibility embraces these areas of function” (Donabedian, 1987, p. 5). Donabedian indicated, however, that providers of care may make efforts to persuade subjects of care to expand their definition of the dimensions of health. The essence of Donabedian’s framework is the physical-physiological function of the individual patient being cared for by the individual practitioner. Examining quality at this level is relatively simple. As one moves outward to include more of the cubical structure, the notions of quality and its assessment become increasingly difficult (see Figure 13-1). When more than one practitioner is involved, both individual and joint contributions to quality must be evaluated. Concepts such as coordination and teamwork must be conceptually and operationally defined. When a person is the subject of care, an important attribute is access. When an aggregate is the subject of care, an important attribute is resource allocation. Access and resource allocation are interrelated, because they each define who gets care, the kind of care received, and how much care is received. As more elements of the cube are included, conflicts among competing objectives emerge. The chief conflict is between the practitioner’s responsibilities to the individual and to the aggregate. The practitioner is expected to have an exclusive commitment to each patient, yet the aggregate demands a commitment to the well-being of society, a situation that may lead to ethical dilemmas for the practitioner. Spending more time with an individual patient decreases access for other patients. Society’s demand to reduce costs for an overall financing program may require raising costs to the individual. From an examination of the cube, logic would suggest that one could build up quality beginning with the primordial, or elemental, cell and increase by increments with the assumption that each increment would contribute positively to a greater total quality (see Figure 13-1). However, the conflicts among competing objectives may preclude this possibility and lead instead to moral dilemmas. Donabedian (1987) identified three objects to evaluate when appraising quality: structure, process, and outcome. A complete quality assessment program requires the simultaneous use of all three constructs and an examination of the relationships among the three. However, researchers have had little success in accomplishing this theoretical goal. Studies designed to examine all three constructs would require sufficiently large samples of various structures, each with the various processes being compared and large samples of subjects who have experienced the outcomes of those processes. The funding and the cooperation necessary to accomplish this goal have not yet been realized; however, examples of nursing research in which two or more aspects have been evaluated are provided in this chapter. A standard of care is a norm on which quality of care is judged. Clinical guidelines, critical paths, and care maps define standards of care for particular situations. According to Donabedian (1987), a practitioner has legitimate responsibility to apply available knowledge when managing a dysfunction or disease state. This management consists of (1) identifying or diagnosing the dysfunction; (2) deciding whether or not to intervene; (3) choosing intervention objectives; (4) selecting methods and techniques to achieve the objectives; and (5) skillfully executing the selected techniques or interventions. Donabedian (1987) recommended the development of criteria to be used as a basis for judging the quality of care. These criteria may take the form of clinical guidelines or care maps based on prior validation that the care contributed to the desired outcomes. The clinical guidelines published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2011) establish norms or standards against which the validity of clinical management can be judged. These norms are now established through clinical practice guidelines available through the National Guideline Clearinghouse within the AHRQ (see http://www.guideline.gov/). However, the core of the problem, from Donabedian’s perspective, is clinical judgment. Analysis of the process of making diagnoses and therapeutic decisions is critical to the evaluation of the quality of care. The emergence of decision trees and algorithms is a response to Donabedian’s concerns and provides a means of evaluating the adequacy of clinical judgments. The style of practitioners’ practice is another dimension of the process of care that influences quality; however, it is problematic to judge what constitutes “goodness” in style and to justify the decisions regarding it. Donabedian (1987) identified the following problem-solving styles: (1) routine approaches to care versus flexibility; (2) parsimony versus redundancy; (3) variations in degree of tolerance of uncertainty; (4) propensity to take risks; and (5) preference for Type I errors versus Type II errors. There are also diverse styles of interpersonal relationships. Westert and Groenewegen (1999, p. 174) suggest that “differences in practice styles are a result of differences in opportunities, incentives, and influences.” They suggest that “there is an (often implicit) idea of what should be done and how, and this shared (local) standard influences the choices made by individual practitioners.” This alternative originates in the borders between economics and sociology and it can be characterized as the social production function approach. The Medical Outcomes Study, described later in this chapter, was designed to determine whether variations in patient outcomes are explained by differences in system of care, clinician specialty, and clinicians’ technical and interpersonal styles (Tarlov et al., 1989). Evidence-based practice (EBP) is another dimension of the process of care that is considered a critical aspect of professional practice (Stetler & Caramanica, 2007). The ultimate goals of EBP are improved patient health status and quality of care (Graham, Bick, Tetroe, Strause, & Harrison, 2011). Thus, the impact of EBP should be assessed through measurement of patient outcomes. Graham et al. (2011) suggest that when planning evaluation of EBP, evaluators should begin by defining a clear question to guide their evaluation. They use the PICO question as a framework for structuring their evaluation question (Straus, Tetroe, Graham, Zwarenstein, & Bhattacharyya, 2009). P refers to the population of interest, which could be the public or a specific patient population. I refers to the implementation of a knowledge translation (KT) intervention. C refers to a comparison or control group who did not receive the intervention, and O refers to the outcome of interest. For instance, the outcome could be improvement in health status. Very few empirical studies have assessed the impact of evidence-based nursing practice on patient outcomes. Davies, Edwards, Ploeg, and Virani (2008) found implementation of best practice guidelines in nursing resulted in improved outcomes in diverse settings, but there was considerable variability in the indicators evaluated, suggesting the need for more research in this area. Chapter 19 provides more details on the synthesis of research evidence and the implementation of EBP in nursing. A third dimension of the examination of the process of care is cost. There are cost consequences to maintaining a specified level of quality of care. Providing more and better care is likely to raise costs but is also likely to produce savings. Economic benefits (savings) result from preventing illness, preventing complications, maintaining a higher quality of life, and prolonging productive life. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has identified the following simple framework for identifying the return on investment for quality initiatives (Sadler, Joseph, Keller, & Rostenberg, 2009): Step 1: Identify your improvement goal. Step 2: Estimate improvement costs. Step 3: Calculate revenue improvement through cost avoidance. Schifalacqua, Mamula, and Mason (2011) used this framework in their development of a cost of care calculator for evaluating an EBP program. The goal was to compare the costs of care before and after implementation of an EBP program. The cost of care analysis focused on potential cost savings realized through the prevention of serious adverse events, such as healthcare-associated infections, pressure ulcers, and falls. Many challenges were revealed in identifying costs that were comparable among healthcare facilities participating in the implementation of the EBP program for preventing serious adverse events. Baseline costs associated with each adverse event were estimated on the basis of U.S. published studies and refined using organizational event data. A related issue is who bears the costs of care. Some measures purported to reduce costs have instead simply shifted costs to another party. For example, a hospital might reduce its costs by discharging a particular type of patient early, but total costs could increase if the necessary community-based health care raised costs above those incurred by keeping the patient hospitalized longer or if complications resulted in rehospitalization. In this case, the third-party provider could experience higher costs. In many cases, the costs are shifted from the healthcare system to the family as out-of-pocket costs or costs that are not covered by healthcare reimbursement systems. Studies examining changes in costs of care should consider total costs, which include out-of-pocket costs. Table 13-1 provides a few examples of studies that examine the direct and indirect costs of care. TABLE 13-1 Studies Examining Costs of Care Structures of care are the elements of organization and administration, as well as provider and patient characteristics, that guide the processes of care. The first step in evaluating structure is to identify and describe the elements of the structure. Various administration and management theories could be used to identify the elements of the structure. These elements might be leadership, tolerance of innovativeness, organizational hierarchy, decision-making processes, distribution of power, financial management, and administrative decision-making processes. Nurse researchers investigating the influence of structural variables on quality of care and outcomes have studied factors such as nurse staffing, nursing education, nursing work environment, hospital characteristics, and organization of care delivery (Table 13-2). TABLE 13-2 Studies Investigating the Relationship between Structural Variables and Outcomes The second step is to evaluate the impact of various structure elements on the process of care and on outcomes. This evaluation requires comparing different structures that provide the same processes of care. In evaluating structures, the unit of measure is the structure. The evaluation requires access to a sufficiently large sample of “like” structures with similar processes and outcomes, which can then be compared with a sample of another structure providing the same processes and examining the same outcomes. For example, in your research you might want to compare various structures providing primary health care, such as the private physician office, the health maintenance organization (HMO), the rural health clinic, the community-oriented primary care clinic, and the nurse-managed center. You might examine surgical care provided within the structures of a private outpatient surgical clinic, a private hospital, a county hospital, and a teaching hospital associated with a health science center. Within each of these examples, the focus of your study would be the impact of structure on processes and outcomes of care. Table 13-2 lists some current outcomes studies that examined the impact of structure of care and process of care on patient outcomes. The federal government requires nursing homes, home healthcare agencies, and hospitals to collect and report specifically measured quality variables to the government. The mandate was established because of considerable variation in the quality of care in these structures. Various government agencies analyze the quality of these structures so that they can adequately oversee the quality of care provided to the American public. These data are made available to the general public so that individuals can make their own determination of the quality of care provided by various nursing homes, home healthcare agencies, or hospitals. Researchers can also access these data for studies of the quality of various structures. To access these data on the Internet, you can search using the phrases nursing home compare, home health compare, and hospital compare. In addition to being able to select a specific hospital, nursing home, or home healthcare agency, you can access considerable general information about quality related to these structures of health care. You can also do a search for Magnet hospitals on the American Nurses Credentialing Center website (http://www.nursecredentialing.org/Magnet/FindaMagnetFacility.aspx/) to check the status of a particular hospital regarding its recognition for excellence in nursing care. Nurses participated in the initial federal involvement in studying the quality of health care. In 1959, two National Institutes of Health (NIH) study sections, the Hospital and Medical Facilities Study Section and the Nursing Study Section, met to discuss concerns about the adequacy and appropriateness of medical care, patient care, and hospital and medical facilities. As a result of their dialogue, a Health Services Research Study Section was initiated. This study section eventually became the Agency for Health Services Research (AHSR), and subsequently the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR). With a growing budget and strong political support, proponents of the AHCPR were becoming a powerful force. They insisted on a change in health care because of the demand for healthcare reform that existed throughout the government and among the public. A reauthorization act changed the name of the AHCPR to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The AHRQ is designated as a scientific research agency. The term policy was removed from the agency name to avoid the perception that the agency determined federal healthcare policies and regulations. The word quality was added to the agency’s name, establishing the AHRQ as the lead federal agency on quality of care research, with a new responsibility to coordinate all federal quality improvement efforts and health services research. The new legislation eliminated the requirement that the AHRQ develop clinical practice guidelines. However, the AHRQ (2011) still supports these efforts through EBP centers and the dissemination of evidence-based guidelines through its National Guideline Clearinghouse (see Chapter 19 for a more detailed discussion of EBP guidelines). The AHRQ, as a part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), supports research designed to improve the outcomes and quality of health care, reduce its costs, address patient safety and medical errors, and broaden access to effective services. The AHRQ website (at http://www.ahrq.gov/) is a valuable source of information about outcomes research, funding opportunities, and results of recently completed research, including nursing research. In 2010, AHRQ awarded $25 million in funding to support efforts by states and health systems to implement and evaluate patient safety approaches and medical liability reform models. In addition, AHRQ invested $17 million to expand projects to help prevent healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), the most common complication of hospital care. The AHRQ initiated several major research efforts to examine medical outcomes and improve quality of care. One of the latest, which is described in the next section, is their comparative effectiveness research. Funding from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act), signed into law in February 2009, allowed AHRQ to expand its work in support of comparative effectiveness research, including enhancing the Effective Health Care Program. A total of $473 million was designated for funding patient-centered outcomes research (AHRQ, 2010). This AHRQ program provides patients, clinicians, and others with evidence-based information to make informed decisions about health care, through activities such as comparative effectiveness reviews conducted through AHRQ’s Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) (see Chapter 19). The AHRQ has a broad research portfolio that touches on nearly every aspect of health care, including: • Outcomes and effectiveness of care • Primary care and care for priority populations • Patient safety/medical errors • Organization and delivery of care and use of healthcare resources • Healthcare costs and financing • Health information technology The Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) was the first large-scale study in the United States to examine factors influencing patient outcomes. The study was designed to identify elements of physician care associated with favorable patient outcomes. Figure 13-2 shows the conceptual framework for the MOS. The following describes the MOS: MOS failed to control for the effects of nursing interventions, staffing patterns, and nursing practice delivery models on medical outcomes. Coordination of care, counseling, and referral activities, which are more commonly performed by nurses than physicians, were inappropriately considered in the MOS to be components of medical practice. Kelly, Huber, Johnson, McCloskey, and Maas (1994) suggested modifications to the MOS framework that would represent the collaboration among physicians, nurses, and allied health practitioners and the influence of their interactions on patient outcomes. These researchers also suggested adding the domain of societal outcomes to include such outcome variables as cost. They noted that “the MOS outcomes framework incorporated areas in which nursing science contributed to health and medical care effectiveness. It also includes structure, process, and outcome variables in which nursing practice overlaps with that of other health professionals” (p. 213). Kelly et al. (1994) further observed that “client outcome categories of the MOS framework that go beyond the scope of physician treatment and intervention alone include functional status, general well-being, and satisfaction with care” (p. 213). A review of the state of the science on nursing-sensitive outcomes published in 2011 confirmed the relevance of these outcomes to nursing practice and suggested several more, including self-care; therapeutic self-care, defined as patients’ ability to manage their disease and its treatment; symptom control; psychosocial functioning; healthcare utilization; and mortality (Doran, 2011). Florence Nightingale has been credited as being the first nurse to collect data in order to identify nursing’s contribution to quality care and to conduct research into patient outcomes (Magnello, 2010; Montalvo, 2007). However, efforts to systematically collect data to assess outcomes in more modern times did not gain widespread attention in the United States until the late 1970s. At that time, concerns about quality of care prompted the development of the “Universal Minimum Health Data Set,” which was followed shortly thereafter by the Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (Kleib, Sales, Doran, Mallette, & White, 2011). These data sets facilitated consistency in data collection among healthcare organizations by prescribing the data elements to be gathered. The aggregated data were then used to perform the assessment of quality of care in hospitals and provide information on patients discharged from hospitals. Over time other countries developed similar data sets. In Canada, “Standards for Management Information Systems” (MIS) were developed in the 1980s. Upon the establishment of the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) in 1994, the MIS became a set of national standards used to collect and report financial and statistical data from health service organizations’ daily operations (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2012). Simultaneously, CIHI implemented a national Discharge Abstract Database (DAD), which has become a key resource. However, as was the case with the Medical Outcomes Study discussed earlier, these data sets did not include information about nursing care delivered to patients in the hospital (Kleib et al., 2011). Without this information, the contribution of nursing care to patient, organizational, and system outcomes was rendered invisible. This major gap in information was addressed by the development of nursing minimum data sets in the Unites States, Canada, and other countries around the world. Outcome studies provide rich opportunities to build a stronger scientific underpinning for nursing practice. Nurse researchers have been actively involved in the effort to examine the outcomes of patient care. Ideally, we would like to understand the outcomes of nursing practice within a one-to-one nurse/patient relationship. However, in most cases, more than one nurse cares for a patient. Therefore, the nursing effect is shared. In addition, nurse managers and nurse administrators have control over the nursing staff and the environment of nursing practice, and this control affects the autonomy of the nurse to implement practice. Therefore, outcomes research must first focus on how nursing care is organized rather than what nurses do. Then, perhaps, we can begin to determine how what nurses do influences patient outcomes (Lake, 2006). We know that nurses do have an effect on patient outcomes. Kramer, Maguire, and Schmalenberg (2006) indicated that a growing body of evidence supports a relationship between empowered shared leadership/governance structure and the implementation of nursing practice. The importance of autonomy in clinical nursing practice is being recognized as critically important to positive patient outcomes. It is important to identify autonomy-enabling structures in the organizational structures of nursing practice. One such structure revealed in a number of nursing studies is the Magnet hospital designation, which represents excellence in nursing in the agency with this designation. Nursing-sensitive outcomes have become an issue because of national concerns related to the quality of care. The demand for professional accountability regarding patient outcomes dictates that nurses be able to identify and document outcomes influenced by nursing care. Efforts to study nursing-sensitive outcomes were initiated by the American Nurses Association (ANA). In 1994, the ANA, in collaboration with the American Academy of Nursing Expert Panel on Quality Health Care, launched a plan to identify indicators of quality nursing practice and to collect and analyze data using these indicators throughout the United States (Mitchell, Ferketich, & Jennings, 1998). The goal was to identify and/or develop nursing-sensitive quality measures. Donabedian’s theory was used as the framework for the project. Together, these indicators were referred to as the ANA Nursing Care Report Card, which could facilitate benchmarking, or setting a desired standard that would allow comparisons of hospitals in terms of their nursing care quality. No one knew empirically what indicators were sensitive to nursing care provided to patients or what the relationships were between nursing inputs and patient outcomes. Every hospital had a different way of measuring the indicators that the ANA had selected. Persuading them to change to a standardized measure of the indicators for consistency among hospitals was a major endeavor (Jennings, Loan, DePaul, Brosch, & Hildreth, 2001; Rowell, 2001). Multiple pilot studies were conducted as nurse researchers and cooperating hospitals put in place the mechanisms required for data collection. These pilot studies identified multiple problems that had to be resolved before the project could go forward. Researchers learned that not only must the indicators be measured consistently but data collection must also be standardized. As studies continued, indicators were amplified and continue to be tested. In 1998, the ANA provided funding to develop a national database to house data collected using nursing-sensitive quality indicators. This became the National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI). Currently, NDNQI has more than 1500 participating organizations. Participation in NDNQI meets requirements for the Magnet Recognition Program®, and 20% of database members participate for that reason. The remaining 80% of the members participate voluntarily to support their evaluation and improvement of nursing care quality and outcomes (Montalvo, 2007). Detailed guidelines for data collection, including definitions and decision guides, are provided by NDNQI (2010). Healthcare organizations submit data electronically via the internet. Statistical methods such as hierarchical mixed models are used to examine the correlation between the nursing workforce characteristics and outcomes (Montalvo, 2007). Quarterly and annual reports of structure, process, and outcome indicators are available 6 weeks after the close of each reporting period. The database is housed at the Midwest Research Institute (MRI), Kansas City, Missouri, and is managed by MRI in partnership with the University of Kansas School of Nursing (Alexander, 2007). The NDNQI nursing sensitive indicators are as follows: 2. Pressure ulcers (hospital acquired, unit acquired) 4. Pain assessment/intervention/reassessment cycle 5. Peripheral intravenous (IV) infiltration 7. Registered Nurse (RN) survey: Job satisfaction; Practice Environment Scale 8. Healthcare associated infections: (a) Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (UTI) (b) Central line–associated bloodstream infection 9. Staff mix (RN; Licensed Practical Nurse [LPN]/Licensed Vocational Nurse [LVN]/Unlicensed Assistive Personnel [UAP]) 10. Nursing care hours provided per patient day 11. Nurse turnover (total, adapted National Quality Forum voluntary, Magnet controllable) 12. RN education/certification California Nursing Outcomes Coalition (CalNOC) was a statewide nursing quality report card pilot project launched in 1996. CalNOC was a joint venture of the ANA/California and the Association of California Nurse Leaders that was funded by ANA. Membership is voluntary and is composed of approximately 300 hospitals from the United States, with pilot work in Sweden, England, and Australia. As its membership grew nationally, CalNOC was renamed the Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes (CALNOC, 2010). It is a not-for-profit corporation, and member hospitals pay a size-based annual data management fee to participate and access CALNOC industry Web-based benchmarking reporting system. 1. Hours per patient-day (RN, LPN, UAP) 4. Percentage of contracted staff utilization (hours) 5. Staff voluntary turnover rate 6. Workload intensity (admissions, discharges, transfers) 7. Sitter hours as percentage of total care hours 8. RN characteristics (education, certification, years of experience) 1. Risk assessment for pressure ulcers (Braden Scale) 2. Time since last risk assessment 3. Risk score (pressure ulcers) 4. Risk status (pressure ulcers, falls) 5. Prevention protocols in place (pressure ulcers, falls) 6. Medication administration accuracy: observed prevalence of 6 key safe practices 7. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC): line insertion practices (who inserted, where, presence of a dedicated team) For further information on these outcome initiatives, you can review Doran, Mildon, and Clarke’s (2011) knowledge synthesis of the state of science on nursing outcomes measurement and international nursing report card initiatives. The knowledge synthesis was a review of nursing-sensitive outcome and report card initiatives in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Belgium.

Outcomes Research

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Theoretical Basis of Outcomes Research

Standards of Care

Practice Styles

Costs of Care

Year

Source

2011

Madsen, L. B., Christiansen, T., Kirkegaard, P., & Pedersen, E. B. (2011). Economic evaluation of home blood pressure telemonitoring: A randomized controlled trial. Blood Pressure, 20(2), 117–125.

2010

Spekle, E. M., Heinrich, J., Hoozemans, M. J., Blatter, B. M., van der Beek, A. J., van Dieen et al. (2010). The cost-effectiveness of the RSI QuickScan program for computer workers: Results of an economic evaluation alongside a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 11, 259–271.

2010

Van Oostrom, S. H., Heymans, M. W., de Vet, H. C., van Tulder, M. W., van Mechelen, W., & Anema, J. R. (2010). Economic evaluation of a workplace intervention for sick-listed employees with distress. Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 67(9), 603–610.

2009

Marchetti, A., & Rossiter, R. (2009). Managing acute acetaminophen poisoning with oral versus intravenous N-acetylcysteine: A provider-perspective cost analysis. Journal of Medical Economics, 12(4), 384–391.

2007

Griffiths, P. D., Edwards, M. H., Forbes, A., Harris, R. L., & Ritchie, G. (2007). Effectiveness of intermediate care in nursing-led inpatient units. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), CD002214.

2006

Phibbs, C. S., Holty, J. C., Goldstein, M. K., Garber, A. M., Wang, Y., Feussner, J.R., et al. (2006). The effect of geriatrics evaluation and management on nursing home use and health care costs: Results from a randomized trial. Medical Care, 44(1), 91–95.

2005

Harris, R., Richardson, G., Griffiths, P., Hallett, N., & Wilson-Barnett, J. (2005). Economic evaluation of a nursing-led inpatient unit: The impact of findings on management decisions of service utility and sustainability. Journal of Nursing Management, 13(5), 428–438.

2004

Altimier, L. B., Eichel, M., Warner, B., Tedeschi, L., & Brown, B. (2004). Developmental care: Changing the NICU physically and behaviorally to promote patient outcomes and contain costs. Neonatal Intensive Care, 17(2), 35–39.

Evaluating Structure

Year

Source

2011

McHugh, M. D., Shang, J., Sloane, D. M., & Aiken, L. H. (2011). Risk factors for hospital-acquired ‘poor glycemic control’: A case control study. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 23(1), 44–51.

2011

Trinkoff, A. M., Johantgen, M., Storr, C. L., Gurses, A. P., Liang, Y., & Han, K. (2011). Nurses’ work schedule characteristics, nurse staffing, and patient mortality. Nursing Research, 60(1), 1–8.

2010

Flynn, L., Liang, Y., Dickson, G. L., & Aiken, L. H. (2010). Effects of nursing practice environments on quality outcomes in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(12), 2401–2406.

2010

Fries, C. R., Earle, C. C., & Silber, J. H. (2010). Hospital characteristics, clinical severity, and outcomes for surgical oncology patients. Surgery, 147(5), 602–609.

2010

Cummings, G. G., Midodzi, W. K., Wong, C. A., & Estabrooks, C. A. (2010). The contribution of hospital nursing leadership styles to 30-day patient mortality. Nursing Research, 59(5), 331–339.

2009

Silber, J. H., Rosenbaum, P. R., Romano, P. S., Rosen, A. K., Wang, Y., Teng, Y., et al. (2009). Hospital teaching intensity, patient race, and surgical outcomes. Archives of Surgery, 144(2), 113–120.

2008

Kutney-Lee, A., & Aiken, L. H. (2008). Effect of nurse staffing and education on the outcomes of surgical patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 59(12), 1466–1469.

2007

Castle, N. G., & Engberg, J. (2007). The influence of staffing characteristics on quality of care in nursing homes. Health Services Research, 42(5), 1822–1847.

2007

Goldman, L. E., Vittinghoff, E., & Dudley, R. A. (2007). Quality of care in hospitals with a high percent of Medicaid patients. Medical Care, 45(6), 579–583.

2007

Standing, M. (2007). Clinical decision-making skills on the developmental journal from student to registered nurse: A longitudinal inquiry. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(3), 257–269.

2006

Mor, V. (2006). Defining and measuring quality outcomes in long term care. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7(8), 532–538.

2006

Rubin, F. H., Williams, J. T., Lescisin, D. A., Mook, W. J., Hassan, S., & Innouye, S. K. (2006). Replicating the Hospital Elder Life Program in a community hospital and demonstrating effectiveness using quality improvement methodology. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 54(6), 969–974.

2005

Donaldson, N., Brown, D. S., Aydin, C. E., Bolton, M. L., & Rutledge, D. N. (2005). Leveraging nurse-related dashboard benchmarks to expedite performance improvement and document excellence. Journal of Nursing Administration, 35(4), 163–172.

2005

Kleinpell, R., & Gawlinski, A. (2005). Assessing outcomes in advanced practice nursing practice: The use of quality indicators and evidence-based practice. AACN Clinical Issues, 16(1), 43–57.

2005

Wilson, I. B., Landon, B. E., Hirschhorn, L. R., McInnes, K., Ding, L., Marsden, P. V., et al. (2005). Quality of HIV care provided by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 143(10), 729–736.

Federal Government Involvement in Outcomes Research

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act

Medical Outcomes Study

Origins of Outcomes/Performance Monitoring

Outcomes Research and Nursing Practice

Nursing-Sensitive Patient Outcomes

The Collaborative Alliance for Nursing Outcomes California Database Project

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Outcomes Research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access