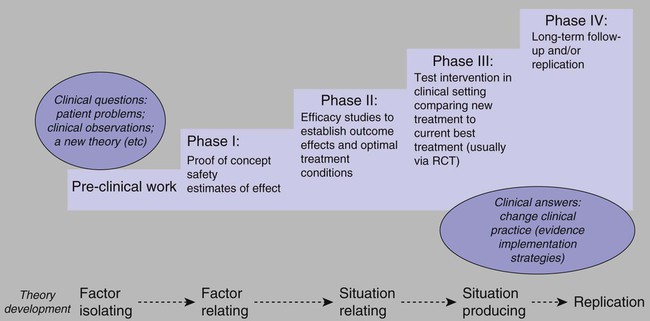

Thousands of intervention-based studies conducted by nurses have contributed to the scientific foundations for nursing practice. Nurse scientists, such as PhD-prepared nurses, not only have conducted individual studies but also have summarized the state of the science in selected areas with meta-analyses and systematic reviews. This high level of synthesis of research findings through meta-analyses and systematic reviews has enabled the pooling of data from multiple studies to formulate statistical and evaluative conclusions about the strength of evidence for interventions. Data compiled from intervention-based studies have guided the development and application of evidence-based practice approaches to care and, in some instances, have contributed to the development of national evidence-based guidelines. One of the most influential meta-analyses that forever changed nursing practice demonstrated that saline was just as effective as heparin flush solution in maintaining the patency of peripheral intravenous locks in adults (Goode et al., 1991). Investigators pooled data from 15 studies involving a total of 3490 patients to draw this conclusion. This would not have been possible without the individual studies conducted to examine the efficacy and effectiveness of a very common nursing intervention. Summaries of intervention-based research are also valuable in determining how strong an intervention might be by gauging its effectiveness among multiple studies. For example, it is vitally important to understand what health promotion interventions work best and under what conditions. To address this issue, Conn, Hafdahl, and Mehr (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of studies focused on physical activity interventions in adults. They found that behavioral approaches were more effective than cognitive ones in improving adults’ activity outcomes. Face-to-face delivery of the intervention, instead of telephone or mail, and individualized-focused interventions, rather than targeting of communities, were more effective in promoting physical activities. Systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-synthesis, and mixed-methods systematic review techniques in the evaluation of interventions across multiple studies provide much stronger evidence for implementing them in practice than one isolated investigation (see Chapter 19 for conducting these research syntheses). The term intervention-based research encompasses a broad range of investigations that examines the effects of any intervention or treatment having relevance to nursing. Nursing interventions are defined as “deliberative cognitive, physical, or verbal activities performed with, or on behalf of, individuals and their families [that] are directed toward accomplishing particular therapeutic objectives relative to individuals’ health and well-being” (Grobe, 1996, p. 50). An expansion of this definition includes nursing interventions that are performed with, or on behalf of, communities. Sidani and Braden (1998, p. 8) view interventions as “treatments, therapies, procedures, or actions implemented by health professionals to and with clients, in a particular situation, to move the clients’ condition toward desired health outcomes that are beneficial to the clients.” Nursing interventions are nurse-initiated and based on nursing classifications of interventions unique to clinical problems or issues addressed by nurses (Bulechek, Butcher, & Dochterman, 2008; Forbes, 2009). Historically, nursing interventions have tended to be viewed as discrete actions, such as “positioning a limb with pillows,” “raising the head of the bed 30 degrees,” and “assessing a patient’s pain.” Interventions can be described more broadly as all of the actions required to address a particular nursing problem or issue. But there is little agreement regarding the conceptualization of interventions and how these discrete actions fit together (McCloskey & Bulechek, 2000). Frameworks have been proposed in moving from isolated action-oriented interventions to more integrative approaches to care. For example, dance therapy might be used as part of a falls reduction initiative (Krampe et al., 2010). In addition, care bundles, which are combinations of interrelated nursing actions, might be the basis for comprehensive approaches to care (Deacon & Fairhurst, 2008; Quigley et al., 2009). These variations in interventions are discussed in the following section. Stage-based interventions are tailored to a specific phase of recovery, response to treatment, or change in behavior. These interventions can be delivered to: (1) study participants as they progress into different phases along a continuum or recovery trajectory over time that require different approaches or (2) discrete or selected samples in various settings at various points in recovery or along a continuum, as with a cross-sectional design, when the intervention is tailored to this stage. Stage-based interventions are used in studies such as testing of smoking cessation techniques when the intervention strategies differ according to whether a person is contemplating quitting smoking, has just quit smoking, or has remained free of smoking (Cahill, Lancaster, & Green, 2010). As a novice researcher, you might want to implement a specific intervention and measure a selected outcome at one point in time. Students are also encouraged to join research teams to examine the effects of interventions. • The Nursing Interventions Classification (NIC), containing 542 direct and indirect care interventions, each of which has an assigned numerical code and that are categorized in seven domains including a new community domain (McCloskey & Bulechek, 2000; Bulechek et al., 2008). The Center for Nursing Classification & Clinical Effectiveness is housed at the University of Iowa College of Nursing and can be accessed online (http://www.nursing.uiowa.edu/excellence/nursing_knowledge/clinical_effectiveness/nic.htm/). • NANDA International (NANDA-I; formerly North American Nursing Diagnosis Association) compiles nursing diagnoses and classifications (http://www.nanda.org/Home.aspx/). NANDA-I publishes the International Journal of Nursing Terminologies and Classifications (IJNTC) quarterly, which is distributed internationally. • Home Health Care Classification System (HHCC) has two taxonomies with 20 Care Components used as a standardized framework to code, index, and classify home health nursing practice (Saba, 2002). • The Omaha System provides a list of diagnoses and an Intervention Scheme designed to describe and communicate multidisciplinary practice intended to prevent illness, improve or restore health, decrease deterioration, and/or provide comfort before death. There are 75 targets or objects of action (Martin, 2005). Martin and Bowles (2008) address the link between practice and research that is predicated on the Omaha System. • The Nursing Intervention Lexicon and Taxonomy (NILT) (Grobe, 1996). Grobe (1996, p. 50) suggested that “theoretically, a validated taxonomy that describes and categorizes nursing interventions can represent the essence of nursing knowledge about care phenomena and their relationship to one another and to the overall concept of care.” Although taxonomies may contain brief definitions of interventions, they do not provide sufficient detail to allow one to implement an intervention. The actions identified in taxonomies may be too discrete for testing and may not be linked to the resolution of a particular patient problem. Populations and settings for which nursing interventions are intended are not elucidated through nursing intervention taxonomies, making them somewhat ambiguous for guiding studies (Sidani & Braden, 1998; Forbes, 2009). Interventions are developed to address problems or issues in practice. The researcher must make a careful analysis of the situational or contextual aspects of a problem or issue prior to designing an intervention. Box 14-1 outlines a list of questions that researchers often ask to focus their attention on who, what, where, and how in designing and implementing an intervention in a study. Upon answering many of these questions, researchers gain a better idea of the planning process needed before undertaking an intervention-based study. Moreover, plans for a grand-scale study may need to be executed in phases, depending on the resources, commitment, support, and feasibility of the study. It is becoming increasingly clear that the design and testing of a nursing intervention require an extensive program of research rather than a single well-designed study (Forbes, 2009; Sidani & Braden, 1998). As the discipline of nursing advances its mission to accumulate a strong practice science, it is apparent that a larger portion of nursing studies must focus on designing and testing interventions. Moreover, intervention research is central to the role of nurses in practice, education, and leadership. Vallerand, Musto, and Polomano (2011), in an extensive review of nurses’ roles in pain management, depict intervention-based research as an integral component of advocacy, quality care, and innovation in patient care (see Figure 14-1). Equally important in advancing nursing science are replication studies, which mimic the design and procedures of interventions tested in previous research. Despite the recognized importance of replicating intervention studies, few have been repeated to validate and verify their results. Intervention research is a methodology that holds great promise as a more effective way of testing interventions. It shifts the focus from causal connection to causal explanation. In causal connection, the focus of a study is to provide evidence that the intervention contributes to the outcome. In causal explanation, in addition to demonstrating that the intervention causes the outcome, the researcher must provide scientific evidence to explain why the intervention contributes to changes in outcomes and how it does so. Causal explanation is theory based. Thus, research focused on causal explanation is guided by theory, and the findings are expressed theoretically. Researchers employ a broad base of methodologies, including qualitative studies, to examine the effectiveness of an intervention. Qualitative approaches offer substantial value to the development, feasibility, and validation of nursing interventions. For example, Van Hecke et al. (2011) used qualitative research in the development and validation of their nursing intervention for promoting lifestyle changes in patients with leg ulcers. A theory or model can be used to guide the development of an intervention as well as provide direction in the design of the study and testing procedures. The theory itself should contain conceptual definitions, propositions linked to hypotheses, and any empirical generalizations available from previous studies (Rothman & Thomas, 1994; Sidani & Braden, 1998). Theoretical constructs serve as frameworks for many nursing intervention studies, for example, risk reductions strategies for cardiovascular disease (Gholizadeh, Davidson, Salamonson, & Worrall-Carter, 2010), improving quality of life with pressure ulcers (Gorecki et al., 2010), and goal-directed therapies for rehabilitative care (Scobbie, Wyke, & Dixon, 2009). Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller, and Costa (2011) derived their activity interventions for nursing home residents with dementia from the Need-Driven Dementia–Compromised Behavior Model for responding to behavioral symptoms. Their randomized double-blind controlled trial involving cognitively impaired residents also linked theory-based underpinnings to the behavioral outcome measures for the study. Not all interventions are examined in the context of theories and theoretical propositions, but some researchers contend that they should, especially when frameworks can be used to help refine interventions and select outcomes (Li, Melnyk, & McCann, 2004). Master’s and doctoral nursing students working in collaboration with faculty researchers or project teams should recognize the value of theory-driven interventions in providing greater clarity to their studies and contributing to the science of intervention theory. Deciding on the best theory to guide intervention research requires: (1) a thorough and thoughtful review and synthesis of the literature (see Chapters 6 and 19); (2) scholarly papers that discuss appropriate theory-based interventions in areas of research interest; (3) interactive discussions among faculty, students, and other nurses about options for an optimal theory to guide interventions; and (4) once a theory has been selected, conversations with the project team to determine its application to the study. Theory-based interventions can be developed for broad populations of patients, such as those with chronic illnesses, and then be more specifically applied to patients with diabetes. For example, Kazer, Bailey, and Whittemore (2010) used a theory-based intervention for self-management of the uncertainty associated with active surveillance for prostate cancer. These researchers discussed an uncertainty management intervention from a theory-based perspective to formulate approaches to care for men with prostate cancer. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice is a specific journal that seeks intervention-based research derived from theoretical frameworks and perspectives. An intervention theory must include a careful description of the problem the intervention will address, the intermediate actions that must be implemented to address the problem, moderator variables that might change the impact of the intervention, mediator variables that might alter the effect of the intervention, and expected outcomes of the intervention. Box 14-2 lists the elements of an intervention theory that are applied to research processes. Models of theories or frameworks help explain the relationships of concepts, interventions, and outcomes. When critically appraising intervention research, students need to keep in mind that a major threat to construct study validity arises if a framework or model used to guide a study and its intervention has no clear link to the development and implementation of the intervention and the interpretation of study findings. Evidence as to how the framework has guided the study needs to be threaded throughout the research report (see Chapter 7 for understanding the inclusion of frameworks in studies). An example of an intervention with minimal scientific rationale is evident in the early work of Schmelzer and Wright (1993). These gastroenterology nurses began a series of studies that examined the procedures for administering an enema. At that time, they found no research in the nursing or medical literature that tested the effectiveness of various enema procedures. Without scientific evidence to justify the use of various procedures for administering enemas—such as the amount of solution, temperature of solution, speed of administration, content of the solution (soap suds, normal saline, or water), positioning of the patient, or measurement of expected outcomes or possible complications—they were faced with relying on the tradition of practice and clinical experience. Their first study involved telephone interviews with nurses across the country in an effort to identify patterns in the methods used to administer enemas; however, this study was unsuccessful in helping Schmelzer and Wright (1996) validate any commonly used techniques to establish guidelines for enema interventions. In their next study, these researchers developed their own protocol for enemas and pilot-tested it on hospitalized patients awaiting liver transplantation. In their subsequent study with a sample of liver transplant patients, these researchers tested for differences in the effects of various enema solutions (Schmelzer, Case, Chappell, & Wright, 2000). Schmelzer (1999-2001) then conducted a study funded by the National Institute for Nursing Research to compare the effects of three enema solutions on the bowel mucosa. Healthy subjects were paid $100 for each of three enemas, after which a small biopsy specimen was collected. These researchers’ experiences illustrate how the lack of scientific evidence for an intervention requires a series of studies before a large-scale study can be launched to answer important research questions. Eventually, these programs of intervention-based research with enemas led to a safety and effectiveness study involving healthy volunteers that showed that enemas using soap suds and tap water produced greater return in bowel evacuation but were more uncomfortable than those using a polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (Schmelzer, Schiller, Meyer, Rugari, & Case, 2004). Although the two former interventions resulted in a more effective response, a higher degree of surface epithelium loss in the bowel was confirmed on biopsy. These investigators concluded that the risks and benefits of selecting an enema solution must be balanced with the desire to produce a better response versus safety concerns, for example, the resultant effects on the bowel and the patient. Fundamental terms that are often mistakenly interchanged with intervention-based research are efficacy and effectiveness. Both words are used to describe an effect of a treatment or intervention; however, these terms are different and should not be used synonymously. Efficacy refers to the ability to produce a desired, beneficial, or therapeutic effect, and it can be determined only in controlled experimental research trials in which study criteria are stringent. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving the testing of drugs or procedures are most often efficacy studies designed to demonstrate, under optimal conditions, the desired outcomes that a drug or procedure produces (Compher, 2010). Efficacy studies require strict control of as many potentially confounding variables as possible to allow measures of efficacy to be quantified. A treatment that is deemed “efficacious” is one that produces good outcomes when subjected to highly controlled, experimental conditions. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials are required in drug development before the U.S. Federal Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) can approve the new drug. Effectiveness of a treatment or intervention indicates that it is capable of producing positive results in a usual or routine care condition. This term is generally reserved for interventions studied in situations in which stringent controls on group assignment are not possible or the study might not include a placebo, control, or comparison group. With effectiveness studies, the new intervention may be compared with the existing standard of care to ascertain whether the new treatment is better, worse, or the same as the existing intervention. These studies still require controls in the design and execution of the interventions but are not nearly as stringent as occurs in RCTs. Effectiveness studies most often use real-world clinicians and patients available to researchers. Table 14-1 contrasts the characteristics of efficacy and effectiveness. TABLE 14-1 Comparison of Characteristics for Efficacy vs. Effectiveness Studies Adapted from Piantadosi, S. (2005). Clinical trials: A methodologic perspective (2nd ed) (p. 323). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; and Gartlehner, G., Hansen, R. A., Nissman, D., Lohr, K. N., & Carey, T. S. (2006). Criteria for distinguishing effectiveness from efficacy trials in systematic reviews. Technical Review, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (AHRQ Publication No. 06-0046.) Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The treatment effect size (ES) refers to the magnitude of effect produced by the intervention. Cohen (1988) and Aberson (2010) provide parameters for qualifying and quantifying the ES but caution that there are inherent risks in applying ES parameters across diverse fields of study because interpretations of ESs can vary. Cohen (1988) identifies a small ES as 0.2, a medium ES as 0.5, and a large ES as 0.8. A small ES of 0.20 for an intervention means a 20% difference can be expected between the intervention and comparison groups. Likewise, a 0.5 ES represents a 50% difference attributed to the intervention. Knowledge of the ES for any intervention is helpful and often necessary for calculations of the sample size needed to provide sufficient statistical power to detect a treatment difference. The nature of the ES also varies from one statistical procedure to the next; it could be the difference in cure rates, a standardized mean difference, or a correlation coefficient. However, the ES function in conducting a power analysis is the same in all procedures (Aberson, 2010; see Chapter 15 for a more detailed discussion of ES and power analysis). A placebo is an intervention intended to have no effect. However, a placebo generally looks, tastes, smells, and/or feels like the test intervention or is experienced like the real study intervention. The purpose of a placebo is to account for how study participants would respond without actually receiving the active intervention. Sham interventions are often used with procedures, and are a variation of a “fake” intervention that omits the essential therapeutic element of the intervention. A “sham” intervention also attempts to control for the placebo effect. Rates for placebo responses do differ depending on the types of interventions and populations studied. For example, the rate for a placebo response with symptom management research can be as high as 90% (Kwekkeboom, 1997). Very complex psychobiological responses occur in the brain, called the real placebo effect, even when an intervention is perceived to be inert or of no known therapeutic value (Benedetti, Carlino, & Pollo, 2011). It is important to note that designs using placebo or sham interventions are typically carefully evaluated by institutional review boards (IRBs) to ensure that patients’ rights are not violated. Sham procedures are often used in research focused on interventions such as healing touch, relaxation therapy, acupuncture, cognitive and behavioral therapy, or any treatment that might produce an effect just from the intervener/participant interactions. To account for the benefits of paying attention to participants or doing something to them that might in and of itself lead to a positive response, researchers sometimes use sham techniques to control for the confounding effects of a treatment. For example, Baird, Murawski, and Wu (2010) studied the efficacy of guided imagery and relaxation on pain reduction, improvements in mobility, and decreased over-the-counter medication use in older adults with osteoarthritis. These investigators provided a sham condition with planned relaxation provided to the comparison group to control for any positive influence on outcomes that might be caused by simply engaging patients in a study. With this type of design, the investigators were able to detect the true effects of the experimental condition under investigation, guided imagery and relaxation. It is always important that the design of a sham technique be similar in many respects to the experimental treatment, such as the circumstances surrounding the encounter with the researcher or intervener, duration of the encounter, and implementation of procedural steps or sequencing of the mock treatment. The term blinding refers to preventing disclosure of group assignment while a study is being conducted to avoid bias or undesirable influence in the ways participants respond and researchers perform. According to the CONSORT (CONsolidated Standards of Reporting Trials, 2011) Transparency Reporting of Trials statement, the term “blinding” or “masking,” which is gaining greater acceptance as the more appropriate designation, “refers to withholding information about the assigned interventions from people involved in the trial who may potentially be influenced by this knowledge.” Procedures for blinding or masking in the conduct of clinical trials are of utmost importance to the validity of findings and estimates of treatment effects. One reason is that participants may respond differently on study outcomes if they have knowledge of their exposure to a treatment condition. Along these same lines, investigators and data collectors can unknowingly or knowingly encourage certain responses from participants in favor of one treatment over another if they are aware of a patient’s treatment group assignment. Those caring for patients in studies could inadvertently share information about treatments that might bias participant performance on outcome measures. Some study conditions even stipulate that knowledge of group assignment be kept from data analysts or statisticians to safeguard against bias in the analysis and interpretation of data. Blinding or masking occurs at various levels. Although this procedure helps to reduce bias in favor of one intervention over another, only 33% of 199 published RCTs from 2007 to 2009 published in 16 nursing journals reported using blinding procedures (Polit, Gillespie, & Griffin, 2011). With single-blinded studies, there are two variations. Study participants are not aware of their treatment assignment, but investigators and research staff may have knowledge of who is in what group. The reverse may be used when participants have knowledge of their treatment group assignment, but this information is not available to the investigators and research staff. For example, children involved in research comparing the calming effects of music alone with those of music with mother’s voice delivered by audiotaped recordings would recognize the contents of the tape if they were alert. Researchers and data collectors may not be told of participant group assignment. Double-blinded studies keep knowledge of study conditions from study participants, investigators, and research staff. When a study is triple-blinded, the participants, researchers, and those involved in data management are unaware of group assignment. Treatment fidelity has to do with the accuracy, consistency, and thoroughness of how an intervention is delivered according to the specified protocol, treatment program, or intervention model. Strict adherence to treatment specifications must be evaluated on an ongoing basis during the course of a study. Thus, intervention fidelity is “the adherent and competent delivery of an intervention by the interventionist as set forth in the research plan” (Santacroce, Maccarelli, & Grey, 2004, p. 63), and this fidelity is of utmost importance to the inference of the study’s internal validity in intervention-based research. Stringent controls for implementation of study procedures are critical to the study’s integrity. Methodological approaches to treatment fidelity include education and training of all persons implementing the treatment, periodic monitoring or surveillance of the implementation of the treatment or fidelity checks (either conspicuous or inconspicuous observation), and retraining and reevaluation of study research staff if deviations from the prescribed protocol for study procedures are found. Gearing et al. (2011) propose a scientific guide to treatment fidelity and discuss implications at all phases of the treatment, including: (1) implementing the design; (2) training the research staff; and (3) monitoring the delivery and receipt of the intervention. Treatment fidelity is important in the conduct of all intervention-based research, but it is especially critical for complex interventions such as those involving information dissemination, social support, counseling, and other interventions intended to bring about changes in health behaviors and psychosocial outcomes. Radziewicz et al. (2009) reported their experiences maintaining treatment fidelity in a study testing a communication support by telephone intervention for older adults with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. These researchers contended that fidelity was maximized by the following: ensuring that the intervention is congruent with relevant theory, standardizing the training, using stringent criteria for conducting fidelity checks to determine interventionist competence, monitoring the delivery of the intervention, and carefully documenting findings. “The degree to which internal validity can be established affects the conclusions’ accuracy drawn from the intervention” (Radziewicz et al., p. 194). Best practices in constructing treatment fidelity criteria and executing sound methodological procedures have been summarized for behavioral research (Bellg et al., 2004; Borrelli et al., 2005). According to Bellg et al. (2004), specific goals should direct fidelity checks. The goals include: (1) ensuring same treatment dose within conditions; (2) ensuring equivalent dose across conditions; and (3) planning for implementation setbacks. Investigators should make provisions to accomplish these goals while formulating criteria by which fidelity or adherence to treatment protocols can be assessed. Often a sampling parameter is set prior to initiation of the study that a certain percentage of study intervention episodes will be evaluated. Manipulation checks are also a critical part of ensuring the integrity of study procedures. These types of checks are valuable in gathering information about circumstances and study conditions that might interfere with or impede implementation of the study intervention. Box 14-3 shows an example of a manipulation check used by interventionists in a study of activity interventions for nursing home residents with dementia (Kolanowski et al., 2011). This type of checklist is also useful to investigators in determining intervention frequency, dose intensity, and protocol deviations. This information not only is critical in recording adherence to the study intervention but also might be included in the analyses of data to separate out or account for variations in exposures to the intervention.

Intervention-Based Research

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Intervention-Based Research Conducted by Nurses

Nursing Interventions

Variations in Nursing Interventions

Nursing Intervention Taxonomies

Problems Examined by Intervention Studies

Programs of Nursing Intervention Research

Note: RCT, randomized controlled trial. Adapted from Vallerand, A. H., Musto, S., & Polomano, R. C. (2011). Nursing’s role in cancer pain management. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 15(4), 250–562; Vallerand, A. H., Musto, S., & Polomano, R. C. (2011). Nursing’s role in cancer pain management. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 15(4), 250–562.

Theory-based Interventions

Scientific Rationale for Interventions

Terminology for Intervention-Based Research

Efficacy versus Effectiveness

Criteria

Efficacy

Effectiveness

Purpose

Test a question

Assess effectiveness

Sample size

Smallest adequate sample size

Large sample size

Study cohort

Homogeneous

Heterogeneous

Population

Study population in tertiary care setting

Study population in initial care setting

Eligibility criteria

Stringent or strict

Minimally restrictive or relaxed

Outcomes

Single or minimal outcomes

Multiple outcomes

Duration

Short study duration

Long study duration

Adverse event recording

Minimal

Comprehensive

Focus of inference

Internal validity

External validity

Analysis

Completer-only analysis

Intent-to-treat analysis

Treatment Effect Size

Placebo and Sham Interventions

Blinding versus Open Label

Treatment Fidelity

Intervention-Based Research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access