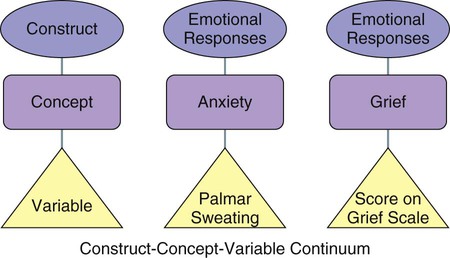

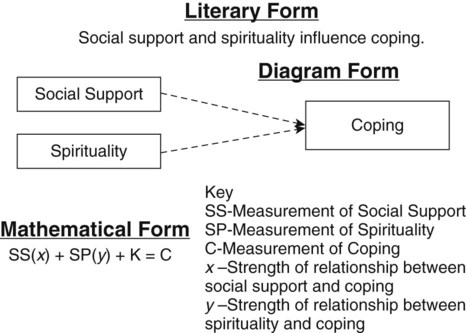

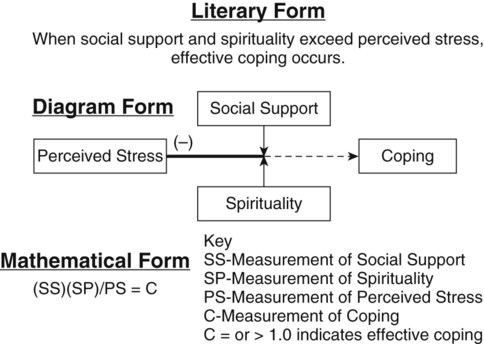

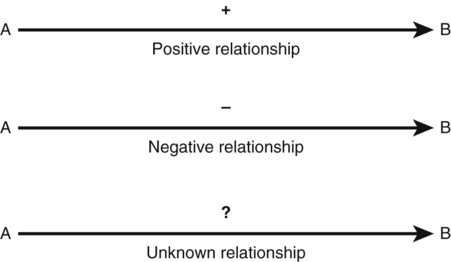

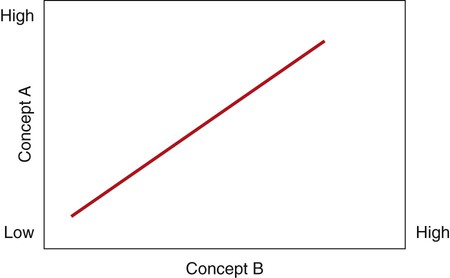

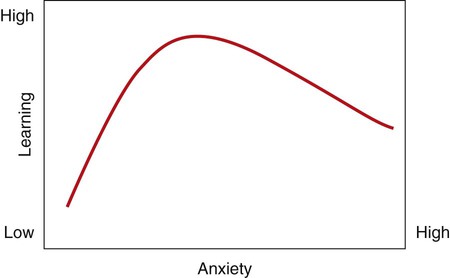

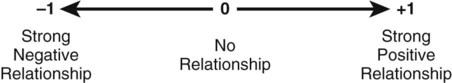

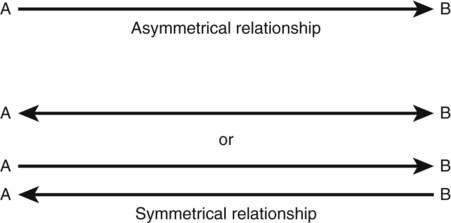

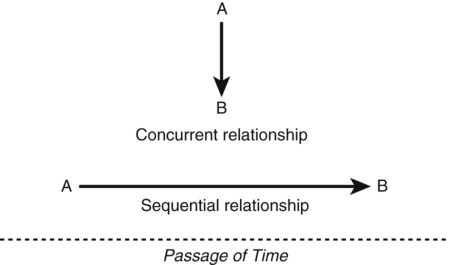

The first step in understanding theories and frameworks is to become familiar with the terms related to theoretical ideas and their application. This section is an introduction to key theoretical terms: concept, relational statement, conceptual model, theory, middle-range theory, and study framework. In response to the ongoing debate and varying opinions about the differences between a conceptual model and a theory or a conceptual model and a philosophy (Meleis, 2012), working definitions of these concepts are presented to facilitate the application of theoretical principles to research. A concept is a term that abstractly describes and names an object, a phenomenon, or an idea, thus providing it with a separate identity or meaning. As a label for a phenomenon or composite of behavior and thoughts, a concept is a concise way to represent the experience or state (Meleis, 2012). An example of a concept is the term anxiety. The concept brings to mind a feeling of uneasiness in the stomach, a rapid pulse rate, and troubling thoughts about future negative outcomes. Consider the concept of hope. What feelings, expectations, and actions are expressed by this label? A relational statement declares that a relationship of some kind exists between or among two or more concepts (Walker & Avant, 2011). Relational statements provide the skeleton of a framework. Clear relational statements are essential for constructing an integrated framework for guiding study design. The relationships expressed in your framework will direct the development of your study’s objectives, questions, or hypotheses. The types of relationships described by the statements will determine the study design and the statistical analyses needed to address the study objectives, questions, or hypotheses. Mature theories, such as physiological theories, have measurable concepts and clear relational statements that can be tested through research. A conceptual model, also known as a grand theory, is a set of highly abstract, related constructs. A conceptual model broadly explains phenomena of interest, expresses assumptions, and reflects a philosophical stance. Nurse scholars have expended time and effort to debate the distinctions between the definitions of theory, conceptual model, conceptual framework, and theoretical framework (Chinn & Kramer, 2011; Meleis, 2012). For example, Watson’s theory of caring has been identified as a theory (Meleis, 2012), a philosophy (Alligood, 2010), and a conceptual model (Fitzpatrick & Whall, 2005). In this textbook, we are using the terms conceptual model, conceptual framework and grand nursing theory interchangeably because our purpose is not to classify theoretical thinking. The purpose of this chapter is to provide the information needed to use concepts, relational statements, and theories or theoretical structures to develop studies and interpret their findings. Middle-range theories present a partial view of nursing reality. Proposed by Merton (1968), a sociologist, middle-range theories are less abstract and address more specific phenomena than grand theories do (Peterson, 2009). They directly apply to practice and focus on explanation and implementation. Middle-range theories may emerge from grand theories or may be developed inductively from research findings. Grounded theory studies are a scientific source of middle-range theory. Some middle-range theories have been developed by combining nursing theories with theories from other disciplines. Some middle-range theories have been developed from clinical practice guidelines. Whatever their source, middle-range theories are sometimes called substantive theories, because they are more concrete than grand theories. One strategy for expressing the theoretical structure guiding a study is to present a map or diagram of the concepts and relational statements. Although some writers call these diagrams conceptual maps (Artinian, 1982; Fawcett, 1999; Newman, 1979, 1986), we are calling them research frameworks to indicate the purpose for which they were developed. A research framework summarizes and integrates what we know about a phenomenon more succinctly and clearly than a literary explanation and allows us to grasp the bigger picture of a phenomenon. A research framework should be supported by references from the literature. These frameworks vary in complexity and accuracy, depending on the available body of knowledge related to the phenomena they are describing. Mapping can also identify gaps in the logic of the theory being used as a framework and reveals inconsistencies, incompleteness, and errors. Now that this basic knowledge of the roles of concepts, relationships, and theories in research has been supplied, the next sections provide a discussion of the analysis and application of each of these components. Concepts are often described as the building blocks of theory. Abstract concepts are descriptive but may not be as applicable to clinical practice or research because of their abstractness. To make a concept more concrete, you can identify how the concept can be measured or observed. These measurable terms are referred to as variables. A variable is more specific than a concept and implies that the term is clearly defined and measurable. The word “variable” implies that the numerical values associated with the term vary from one instance to another. A variable related to anxiety might be “palmar sweating,” which the researcher can measure by assigning a numerical value to the amount of sweat on the subject’s palm. The links among constructs, concepts, and variables are displayed in Figure 7-1. On the left of the figure is the construct-to-variable continuum. The other two sets of shapes are examples of a construct, concept, and variable. Notice that a concept may have multiple ways of being measured. For example, anxiety could be measured by palmar sweating, the State-Trait Anxiety Scale, or a checklist of behaviors such as pacing, wringing one’s hands, and expressing worries. Defining concepts allows us to be consistent in the way we use a term in practice, apply it to a theory, and measure it in a study. A conceptual definition differs from the denotative (or dictionary) definition of a word. A conceptual definition (connotative meaning) is more comprehensive than a denotative definition because it includes associated meanings the word may have. For example, a connotative definition may associate the term “fireplace” with images of hospitality and warm comfort, whereas the dictionary definition would be a rock or brick structure in a house designed for burning wood. A conceptual definition can be established through concept synthesis, concept derivation, or concept analysis (Walker & Avant, 2011). In nursing, many phenomena have not yet been identified as discrete entities. Recognizing, naming, and describing these phenomena are often critical steps to understanding the process and outcomes of nursing practice. In your clinical practice, you may notice patterns of behavior or find patterns in empirical data. You may name a concept that emerges during data analysis in a qualitative study. The process of describing and naming a previously unrecognized concept is concept synthesis. Nursing studies often involve previously unrecognized and unnamed phenomena that must be named and carefully defined. Lee and Coakley (2011) conducted a concept synthesis of geropalliative care. Conceptual and philosophical works had examined gerontology and palliative care separately but the combined term lacked conceptual clarity. This lack of clarity was viewed as hindering progress in this interdisciplinary area of study. Lee and Coakley (2011) concluded that geropalliative care is “both a philosophical stance and structured interdisciplinary model of care delivery that guides care to patients and families during the last 5 years of life, irrespective of disease” (p. 247). They describe the critical attributes of geropalliative care as “high risk for ineffective pain management,” “geriatric syndromes,” “chronic, comorbid conditions,” “risk for ineffective communication,” and “beneficial in the absence of disease” (p. 247). The context of the concept includes end-of-life trajectories that are unpredictable, “shrinking social networks, insurance limitations,” and “multiple settings” (p. 247). Concept synthesis can be an important element in the development of nursing theory (Walker & Avant, 2011). Concept derivation may occur when the researcher or theorist finds no concept in nursing to explain a phenomenon (Walker & Avant, 2011). Concepts identified or defined in theories of other disciplines may provide insight. In concept derivation, one concept is transposed from one of field of knowledge to another. If a conceptual definition is found in another discipline, it must be examined to evaluate its fit with the new field in which it will be used. The conceptual definition may need to be modified so that it is meaningful within nursing and consistent with nursing thought (Walker & Avant, 2011). For example, the concept of weathering, from physical material science, means the alteration of a material exposed over time to sun, wind, and precipitation. Health researchers, including nurses, define weathering as the alteration of fundamental components of the human organism when exposed over time to stress, unsupportive environments, and limited resources (Holzman et al., 2009). Concept derivation is a creative process that can be fostered by thinking deeply and having a willingness to learn about processes and theories in other disciplines. Concept analysis is a strategy that identifies a set of characteristics essential to the connotative meaning of a concept. The procedure will require you to explore the various ways the term is used and to identify a set of characteristics that clarify the range of objects or ideas to which that concept may be applied (Walker & Avant, 2011). These essential characteristics, called defining attributes or criteria, provide a means to distinguish the concept from similar concepts. Several approaches to concept analysis have been described in the nursing and healthcare literature. Because the approaches have varying philosophical foundations and products, nurse theorists and researchers must select the concept analysis approach that best suits their purposes in a specific situation. For example, a researcher attempting to measure the phenomenon of barriers may choose Walker and Avant’s (2011) approach because of its product of a theoretical definition. Deepened understanding of the theoretical definitions allows the researcher to critically appraise the construct validity of instruments or methods being considered to measure the concept in a study. An emerging nurse theorist may choose Rodger’s evolutionary approach to understand the contextual influences on and changes in the meaning of the concept over time. Several writers have compared the different types of concept analysis (Cronin, Ryan, & Coughlan, 2010; Duncan, Cloutier, & Bailey, 2007; Hupcey & Penrod, 2005; Risjord, 2009; Weaver & Mitcham, 2008). Several concept analysis strategies used in nursing and health care are listed in Table 7-1. In addition, a number of concept analyses have been published in the nursing literature, such as those listed in Table 7-2. The following section provides an example of how one group of researchers developed a conceptual definition for the concept frailty through an analysis of published definitions. TABLE 7-1 TABLE 7-2 Concept Analyses Using Different Methods With the growth in the proportion of the population that are over age 65 years, there is increased urgency in preventing frailty among older people who live in the community (Gobbens, Luijkx, Wijnen-Sponselee, & Schols, 2010). An extensive literature review was done to identify conceptual and operational definitions of frailty. From their review of 18 conceptual definitions, Gobbens et al. concluded that “frailty is a dynamic state affecting an individual who experiences losses in one or more domains of human functioning (physical, psychological, social) that are caused by the influence of a range of variables and which increases the risk of adverse outcomes” (p. 85). The definition allows researchers to distinguish frailty from disability and comorbidity. The refinement of the conceptual definition has limited value without a practical way to measure it (Gobbens et al., 2010). Having found no operational definition that was a logical fit with the conceptual definition proposed, the researchers identified their next step to be developing an operational definition of frailty consistent with the conceptual definition. Relational statements describe the direction, shape, strength, symmetry, sequencing, probability of occurrence, necessity, and sufficiency of a relationship (Walker & Avant, 2011). One statement may have several of these characteristics; each characteristic is not exclusive of the others. Statements may be expressed as words in a sentence (literary form), as shapes and arrows (diagram form), or as equations (mathematical form). In nursing, the literary and diagrammatic forms of statements are used most frequently. Figure 7-2 displays the three forms of simple statements of relationships among spiritual perspective, social support, and coping. Notice in the diagram in Figure 7-2 that dotted arrows are used to indicate a relationship about which little is known. The mathematical form indicates the same relationships. Figure 7-3 provides literary, diagrammatic, and mathematical forms of a more complex statement among the previous concepts with the addition of perceived stress. Notice the change in the arrow between perceived stress and coping. The arrow is darker and heavier until spiritual perspective and social support modify the relationship. The mathematical form proposes that when the product of spiritual perspective and social support is greater than perceived stress, coping will be greater. When the product is less than perceived stress, coping is diminished. The direction of a relationship may be positive, negative, or unknown (Fawcett, 1999). A positive linear relationship implies that as one concept changes (the value or amount of the concept increases or decreases), the second concept will also change in the same direction. For example, the literary statement, “As stress increases (A), the risk of illness (B) increases,” expresses a positive relationship. This positive relational statement could also be expressed as “As stress decreases (A), the risk of illness (B) decreases.” The nature of the relationship between two concepts may be unknown because it has not been studied or because study findings have been conflicting. For example, consider two studies that included the concepts of coping and social support. Tkatch et al. (2011) found that the number of people in the social networks of African American patients in cardiac rehabilitation (N = 115) and their health-related social support had weak, but statistically significant relationships with their coping efficacy. In contrast, Jackson et al. (2009) found nonsignificant relationships among social support and coping in a longitudinal study of 88 parents who had a child with a brain tumor. From the findings, we can conclude that although there is evidence that a relationship exists between these two concepts, the studies examining that relationship have conflicting findings. Conflicting findings may result from differences in the researchers’ definitions and measurements of the two concepts in various studies. Another reason for conflicting findings may be that an unidentified confounding variable exists that changes the relationship between coping and social support. Whatever the reason, conflicting findings about a relationship between concepts could be indicated by a question mark. Figure 7-4 has diagrams representing the directional characteristics of relationships. More details on diagramming relational statements are presented in Chapter 8. Most relationships are assumed to be linear, and statistical tests are conducted to identify linear relationships. In a linear relationship, the relationship between the two concepts remains consistent regardless of the values of each of the concepts. For example, if the value of A increases by 1 point each time the value of B increases by 1 point, then the values continue to increase at the same rate whether the value is 2 or 200. The relationship can be illustrated by a straight line, as shown in Figure 7-5. Relationships can also be curvilinear or form some other shape. In a curvilinear relationship, the relationship between two concepts varies according to the relative values of the concepts. The relationship between anxiety and learning is a good example of a curvilinear relationship. Very high or very low levels of anxiety are associated with low levels of learning, whereas moderate levels of anxiety are associated with high levels of learning (Bierman, Comijs, Rijmen, Jonker, & Beekman, 2008). This type of relationship is illustrated by a curved line, as shown in Figure 7-6. The strength of a relationship is the amount of variation explained by the relationship. Some of the variation in a concept, but not all, is associated with variation in another concept (Fawcett, 1999). In discussing the strength of a relationship, researchers sometimes use the term effect size. The effect size explains how much “effect” variation in one concept has on variation in a second concept. The statistic r is the coefficient obtained by performing the statistical procedure known as Pearson’s product-moment correlation (see Chapter 23). A value of 0 indicates no strength, whereas a value of +1 or −1 indicates the greatest strength (see Figure 7-7). When the correlation is large, a greater portion of the variation can be explained by the relationship; in others, only a moderate or a small portion of the variation can be explained by the relationship. For example, Tkatch et al. (2011) found a relationship of r = 0.22 (p < 0.05) between health-related social support and coping efficacy. The strength of the relationship meant that a small portion of the variance in coping was explained by variations in health-related social support (see Chapter 23 for additional information). The + or − does not have an impact on the strength of the relationship. For example, r = −0.35 is as strong as r = +0.35. A weak relationship is usually considered one with an r value of 0.1 to 0.3; a moderate relationship is one with an r value of 0.31 to 0.5; and a strong relationship is one with an r value greater than 0.5. The greater the strength of a relationship, the easier it is to detect relationships between the variables being studied. This idea will be explored further in the chapters on sampling, measurement, and data analysis (Chapters 15, 16, and 23, respectively). Relationships may be symmetrical or asymmetrical. In an asymmetrical relationship, if A occurs (or changes), then B will occur (or change); but there may be no indication that if B occurs (or changes), A will occur (or change). An asymmetrical relationship is not reversible (Fawcett, 1999). You can think of this relationship as a one-way street, with influence going only in one direction. Bradford and Petrie (2008) found an asymmetrical relationship between internalized ideal of a thin body and body dissatisfaction in their study of disordered eating among 236 first-year, female college students. The internalized thin body ideal affected body dissatisfaction, but the reverse was not true (see Figure 7-8). A symmetrical relationship is complex and contains two statements, such as if A changes, B will change and if B changes, A will change (Fawcett, 1999). You may think of the relationship between these concepts as a two-way street with influence going in both directions. These relationships may also be called reciprocal or reversible. An example is the symmetrical relationship between quality of life and perceived health among patients after heart surgery (Mathisen et al., 2007). The researchers found that quality of life influenced perceived health and that perceived health influenced quality of life, indicating a symmetrical relationship between the concepts. A second example comes from the study by Bradford and Petrie (2008). They found a symmetrical (reciprocal) relationship between depression and disordered eating in their study with adolescent females (see Figure 7-8). The amount of time that elapses between one concept and another is stated as the sequential nature of a relationship. If the two concepts occur simultaneously, the relationship is concurrent (Fawcett, 1999). When there is a change in one concept, there is change in the other at the same time. If one concept changes and the second concept changes later, the relationship is sequential. Another example from Bradford and Petrie’s study (2008) was a hypothesized concurrent relationship between internalizing the thin body ideal and dissatisfaction with one’s body. Their findings provided mixed support for the relationship. They also hypothesized that depression would predict later pathological eating. This sequential relationship was supported by their findings. These relationships are diagrammed in Figure 7-9. A relationship can be deterministic or probabilistic depending on the degree of certainty that it will occur. Deterministic (or causal) relationships are statements of what always occurs in a particular situation. For example, among Thai patients with heart failure, nurse researchers found that symptom status, social support, general health perception, and functional status had causal relationships with health-related quality of life (Phuangphaka, Veena, Chanokporn, & Sloan, 2008). Scientific laws are another example of deterministic relationships (Fawcett, 1999). A causal relationship is expressed as follows: A probability statement expresses the probability that something will happen in a given situation (Fawcett, 1999). This relationship is expressed as follows: In a necessary relationship, one concept must occur for the second concept to occur (Fawcett, 1999). For example, one could propose that if sufficient fluids are administered (A), and only if sufficient fluids are administered, the unconscious patient will remain hydrated (B). This relationship is expressed as follows: A sufficient relationship states that when the first concept occurs, the second concept will occur, regardless of the presence or absence of other factors (Fawcett, 1999). A statement could propose that if a patient is immobilized in bed longer than a week, he or she will lose bone calcium, regardless of anything else. This relationship is expressed as follows:

Frameworks

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Definition of Terms

Concept

Relational Statements

Conceptual Models

Theory

Middle-Range Theories

Research Frameworks

Understanding Concepts

Concept Synthesis

Concept Derivation

Concept Analysis

Type of Concept Analysis (Author[s], Date)

Unique Characteristics

Principle-based (Hupcey & Penrod, 2005)

Analysis guided by linguistic, epistemological, pragmatic, and logical principles

Ordinary use (Wilson, 1963)

Foci of analysis are exemplars (cases) that are used to identify criteria, antecedents, and consequences

Evolutionary method (Rodgers, 2000 )

Contextual analysis of how the concept has developed over time in different settings

Hybrid (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000)

Contextual analysis and data collection in the field leading to conclusions about how concept has developed over time in different settings

Linguistic, pragmatic approach (Walker & Avant, 2011)

Analysis of explicit and implicit concept definitions in the literature to identify criteria, antecedents, and consequences for pragmatic purposes in practice and research

Simultaneous (Haase, Britt, Coward, Leidy, & Penn, 1992)

Examines closely related concepts to distinguish their unique meanings as well as areas of overlap

Concept Analyzed

Method of Concept Analysis

Advanced nursing practice (Ruel & Motyka, 2009)

Principle-Based (Hupcey & Penrod, 2005)

Dance in mental health nursing (Ravelin, Kylma, & Korhonen, 2006)

Hybrid (Schwartz-Barcott & Kim, 2000)

Clinical reasoning (Simmons, 2010)

Evolutionary method (Rodgers, 2000)

Acculturation in Filipino immigrants (Serafica, 2011)

Linguistic, Pragmatic (Walker & Avant, 2011)

Ethical demand in nursing (Mårtenson, Fägerskiöld, Runeson, & Berterö, 2009)

Simultaneous (Haase, Britt, Coward, Leidy, & Penn, 1992)

Importance of a Conceptual Definition: An Example

Examining Relational Statements

Characteristics of Relational Statements

Direction

Shape

Strength

Symmetry

Sequencing

Probability of Occurrence

Necessity

Sufficiency

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Frameworks

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access