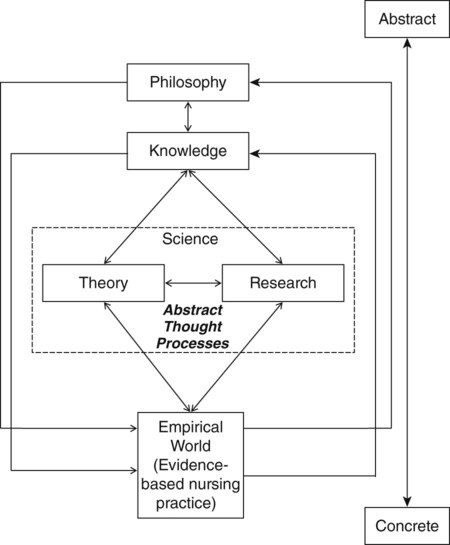

Welcome to the world of nursing research. You might think it is strange to consider research a “world,” but research is truly a new way of experiencing reality. Entering a new world requires learning a unique language, incorporating new rules, and using new experiences to learn how to interact effectively within that world. As you become a part of this new world, your perceptions and methods of reasoning will be modified and expanded. Understanding the world of nursing research is critical to providing evidence-based care to your patients. Since the 1990s, there has been a growing emphasis for nurses—especially advanced practice nurses (nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, nurse anesthetists, and nurse midwives), administrators, educators, and nurse researchers—to promote an evidence-based practice in nursing (Brown, 2009; Craig & Smyth, 2012; Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011). Evidence-based practice in nursing requires a strong body of research knowledge that nurses must synthesize and use to promote quality care for their patients, families, and communities. We developed this text to facilitate your understanding of nursing research and its contribution to the implementation of evidenced-based nursing practice. The American Nurses Association (ANA, 2012) developed the following definition of nursing that identifies the unique body of knowledge needed by the profession: “Nursing is the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations.” On the basis of this definition, nursing research is needed to generate knowledge about human responses and the best interventions to promote health, prevent illness, and manage illness (ANA, 2010b). Many nurses hold the view that nursing research should focus on acquiring knowledge that can be directly implemented in clinical practice, which is sometimes referred to as applied research or practical research (Brown, 2009; Mackay, 2009). However, another view is that nursing research should include studies of nursing education, nursing administration, health services, and nurses’ characteristics and roles as well as clinical situations. Riley, Beal, Levi, and McCausland (2002) support this second view and believe nursing scholarship should include education, practice, and service. Research is needed to identify teaching-learning strategies to promote nurses’ management of practice. Thus, nurse researchers are involved in building a science for nursing education so the teaching-learning strategies used are evidence-based (National League for Nursing [NLN], 2009). Nurse administrators are involved in research to enhance nursing leadership and the delivery of quality, cost-effective patient care. Studies of health services and nursing roles are important to promote quality outcomes in the nursing profession and the healthcare system (Doran, 2011). To best explore nursing research, we have developed a framework to help establish connections between research and the various elements of nursing. The framework presented in the following pages links nursing research to the world of nursing and is used as an organizing model for this textbook. In the framework model (see Figure 1-1), nursing research is not an entity disconnected from the rest of nursing but rather is influenced by and influences all other nursing elements. The concepts in this model are pictured on a continuum from concrete to abstract. The discussion introduces this continuum and progresses from the concrete concept of the empirical world of nursing practice to the most abstract concept of nursing philosophy. The use of two-way arrows in the model indicates the dynamic interaction among the concepts. As previously mentioned, Figure 1-1 presents the components of nursing on a concrete-abstract continuum. This continuum demonstrates that nursing thought flows both from concrete to abstract thinking and from abstract to concrete. Concrete thinking is oriented toward and limited by tangible things or by events that we observe and experience in reality. Thus, the focus of concrete thinking is immediate events that are limited by time and space. Most nurses believe they are concrete thinkers because they focus on the specific actions in nursing practice. Abstract thinking is oriented toward the development of an idea without application to, or association with, a particular instance. Abstract thinkers tend to look for meaning, patterns, relationships, and philosophical implications. This type of thinking is independent of time and space. Currently, graduate nursing education fosters abstract thinking, because it is an essential skill for developing theory and creating an idea for study. Nurses assuming advanced roles and registered nurses (RNs) need to use both abstract and concrete thinking. For example, a nurse practitioner must explore the best research evidence about a practice problem (abstract thinking) before using his or her clinical expertise to diagnose and manage an individual patient’s health problem (concrete thinking). RNs also use abstract and concrete thinking to develop and refine protocols and policies based on current research to direct patient care. The practice of nursing takes place in the empirical world, as demonstrated in Figure 1-1. The scope of nursing practice varies for the RN and the advanced practice nurse (APN). RNs provide care to and coordinate care for patients, families, and communities in a variety of settings. They initiate interventions as well as carry out treatments authorized by other healthcare providers (ANA, 2010a). APNs, such as nurse practitioners, nurse anesthetists, nurse midwives, and clinical nurse specialists, have an expanded practice. Their knowledge, skills, and expertise promote role autonomy and overlap with medical practice. APNs usually concentrate their clinical practice in a specialty area, such as acute care, pediatrics, gerontology, adult or family primary care, psychiatric-mental health, women’s health, maternal child, or anesthesia (ANA, 2010b). You can access the most current nursing scope and standards for practice from the ANA (2010a). Within the empirical world of nursing, the goal is to provide evidence-based practice to improve the health outcomes of individuals, families, and communities (see Figure 1-1). The aspects of evidence-based practice and the significance of research in developing evidence-based practice are covered later in this chapter. People tend to validate or test the reality of their existence through their senses. In everyday activities, they constantly check out the messages received from their senses. For example, they might ask, “Am I really seeing what I think I am seeing?” Sometimes their senses can play tricks on them. This is why instruments have been developed to record sensory experiences more accurately. For example, does the patient just feel hot or actually have a fever? Thermometers were developed to test this sensory perception accurately. Through research, the most accurate and precise measurement devices have been developed to assess the temperature of patients on the basis of age and health status (Waltz, Strickland, & Lenz, 2010). Thus, research is a way to test reality and generate the best evidence to guide nursing practice. Nurses use a variety of research methods to test their reality and generate nursing knowledge, including quantitative research, qualitative research, outcomes research, and intervention research. Quantitative research, the most frequently conducted method, is a formal, objective, systematic methodology to describe variables, test relationships, and examine cause-and-effect interactions (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002). Since the 1980s, nurses have been conducting qualitative research to generate essential theories and knowledge for nursing. Qualitative research is a rigorous, interactive, holistic, subjective research approach used to describe life experiences and give them meaning (Marshall & Rossman, 2011; Munhall, 2012). Both quantitative and qualitative research methods are important to the development of nursing knowledge (Fawcett & Garity, 2009; Munhall, 2012; Shadish et al., 2002). Some researchers effectively combine these two methods in implementing mixed method research to address selected nursing research problems (Creswell, 2009). Medicine, healthcare agencies, and now nursing are focusing on the outcomes of patient care. Outcomes research is an important scientific methodology that has evolved to examine the end results of patient care and the outcomes for healthcare providers, such as RNs, APNs, and physicians, and for healthcare agencies (Doran, 2011). Nurses are also engaged in intervention research, a methodology for investigating the effectiveness of nursing interventions in achieving the desired outcomes in natural settings (Forbes, 2009). These different types of research are all essential to the development of nursing science, theory, and knowledge (see Figure 1-1). Nurses have varying roles related to research that include conducting research, critically appraising research, and using research evidence in practice. Generating a scientific knowledge base with implementation in practice requires the participation of all nurses in a variety of research activities. Some nurses are developers of research and conduct studies to generate and refine the knowledge needed for nursing practice. Others are consumers of research and use research evidence to improve their nursing practice. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN, 2006) and ANA (2010a, 2010b) have published statements about the roles of nurses in research. No matter their education or position, all nurses have roles in research and some ideas about those roles are presented in Table 1-1. The research role a nurse assumes usually expands with his or her advanced education, expertise, and career path. Nurses with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree have knowledge of the research process and skills in reading and critically appraising studies. They assist with the implementation of evidence-based guidelines, protocols, algorithms, and policies in practice. In addition, these nurses might provide valuable assistance in identifying research problems and collecting data for studies. TABLE 1-1 Nurses’ Participation in Research at Various Levels of Education Nurses with a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) have undergone the educational preparation to critically appraise and synthesize findings from studies to revise or develop protocols, algorithms, or policies for use in practice. They also have the ability to identify and critically appraise the quality of evidence-based guidelines developed by national organizations. APNs and nurse administrators have the ability to lead healthcare teams in making essential changes in nursing practice and in the healthcare system on the basis of current research evidence. Some MSN-prepared nurses conduct studies but usually do so in collaboration with other nurse scientists (AACN, 2006; ANA 2010a). The doctorate in nursing can be practice focused (doctorate of nursing practice [DNP]) or research focused (doctorate of philosophy [PhD]). Nurses with DNPs are educated to have the highest level of clinical expertise, with the ability to translate scientific knowledge for use in practice. These doctorally prepared nurses have advanced research and leadership knowledge to develop, implement, evaluate, and revise evidence-based guidelines, protocols, algorithms, and policies for practice (Clinton & Sperhac, 2006). In addition, DNP-prepared nurses have the expertise to conduct and/or collaborate with clinical studies. PhD-prepared nurses assume a major role in the conduct of research and the generation of nursing knowledge in a selected area of interest (Brar, Boschma, & McCuaig, 2010). These nurse scientists often coordinate research teams that include DNP-, MSN-, and BSN-prepared nurses to facilitate the conduct of high-quality studies in a variety of healthcare agencies. Postdoctorate nurses usually assume full-time researcher roles and have funded programs of research. They lead interdisciplinary teams of researchers and sometimes conduct studies in multiple settings. These scientists often are identified as experts in selected areas of research and provide mentoring of new PhD-prepared researchers (AACN, 2006) (see Table 1-1). Abstract thought processes influence every element of the nursing world. In a sense, they link all the elements together. Without skills in abstract thought, we are trapped in a flat existence; we can experience the empirical world, we cannot explain or understand it (Abbott, 1952). Through abstract thinking, however, we can test our theories (which explain the nursing world) and then include them in the body of scientific knowledge (Smith & Liehr, 2008). Abstract thinking also allows scientific findings to be developed into theories (Munhall, 2012). Abstract thought enables both science and theories to be blended into a cohesive body of knowledge, guided by a philosophical framework, and applied in clinical practice (see Figure 1-1). Thus, abstract thought processes are essential for synthesizing research evidence and knowing when and how to use this knowledge in practice. Three major abstract thought processes—introspection, intuition, and reasoning—are important in nursing (Silva, 1977). These thought processes are used in critically appraising and applying best research evidence in practice, planning and implementing research, and developing and evaluating theory. Intuition is an insight into or understanding of a situation or event as a whole that usually cannot be logically explained (Smith, 2009). Because intuition is a type of knowing that seems to come unbidden, it may also be described as a “gut feeling” or a “hunch.” Because intuition cannot be explained with ease scientifically, many people are uncomfortable with it. Some even say that it does not exist. Sometimes, therefore, the feeling or sense is suppressed, ignored, or dismissed as silly. However, intuition is not the lack of knowing; rather, it is a result of deep knowledge—tacit knowing or personal knowledge (Benner, 1984; Polanyi, 1962, 1966). The knowledge is incorporated so deeply within that it is difficult to bring it consciously to the surface and express it in a logical manner. One of the most commonly cited examples of nurses’ intuition is their recognition of a patient’s physically deteriorating condition. Odell, Victor, and Oliver (2009) conducted a review of the research literature and described nurses’ use of intuition in clinical practice. They noted that nurses have an intuition or a knowing that something is not right with their patients by recognizing changes in behavior and physical signs. Through clinical experience and the use of intuition, nurses are able to recognize patterns of deviations from the normal clinical course and to know when to take action. Reasoning is the processing and organizing of ideas in order to reach conclusions. Through reasoning, people are able to make sense of their thoughts and experiences. This type of thinking is often evident in the verbal presentation of a logical argument in which each part is linked together to reach a logical conclusion. Patterns of reasoning are used to develop theories and to plan and implement research. Barnum (1998) identified four patterns of reasoning as being essential to nursing: (1) problematic, (2) operational, (3) dialectic, and (4) logistic. An individual uses all four types of reasoning, but frequently one type of reasoning is more dominant than the others. Reasoning is also classified by the discipline of logic into inductive and deductive modes (Chinn & Kramer, 2008). Operational reasoning involves the identification of and discrimination among many alternatives and viewpoints. It focuses on the process (debating alternatives) rather than on the resolution (Barnum, 1998). Nurses use operational reasoning to develop realistic, measurable health goals with patients and families. Nurse practitioners use operational reasoning to debate which pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments to use in managing patient illnesses. In research, operationalizing a treatment for implementation and debating which measurement methods or data analysis techniques to use in a study require operational thought (Kerlinger & Lee, 2000; Waltz et al., 2010).

Discovering the World of Nursing Research

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Definition of Nursing Research

Framework Linking Nursing Research to the World of Nursing

Concrete-Abstract Continuum

Empirical World

Reality Testing Using Research

Roles of Nurses in Research

Educational Preparation

Research Functions

BSN

Read and critically appraise studies. Use best research evidence in practice with guidance. Assist with problem identification and data collection.

MSN

Critically appraise and synthesize studies to develop and revise protocols, algorithms, and policies for practice. Implement best research evidence in practice. Collaborate in research projects and provide clinical expertise for research.

DNP

Participate in evidence-based guideline development. Develop, implement, evaluate, and revise as needed protocols, policies, and evidence-based guidelines in practice. Conduct clinical studies, usually in collaboration with other nurse researchers.

PhD

Major role in conducting independent research and contributing to the empirical knowledge generated in a selected area of study. Obtain initial funding for research. Coordinate research teams of BSN, MSN, and DNP nurses.

Post-doctorate

Assume a full researcher role with a funded program of research. Lead and/or participate in nursing and interdisciplinary research teams. Identified as experts in their areas of research. Mentor PhD-prepared researchers.

Abstract Thought Processes

Intuition

Reasoning

Operational Reasoning

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Discovering the World of Nursing Research

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access