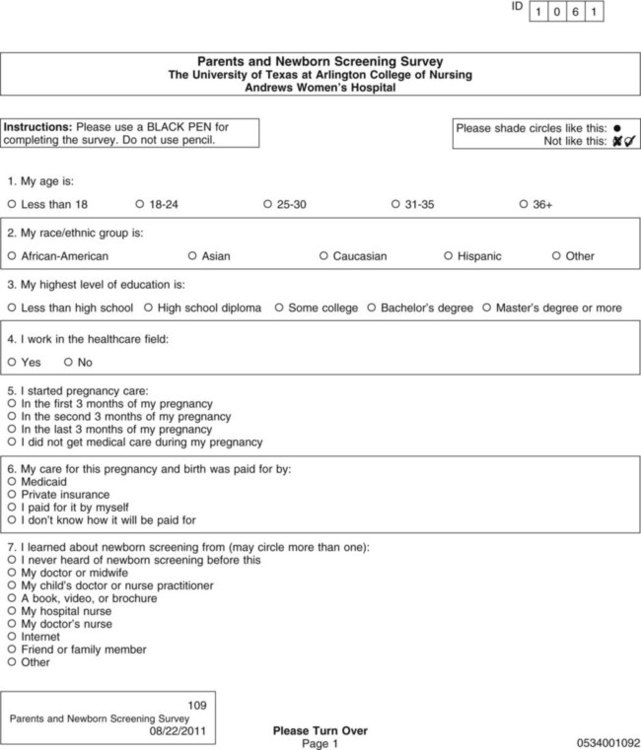

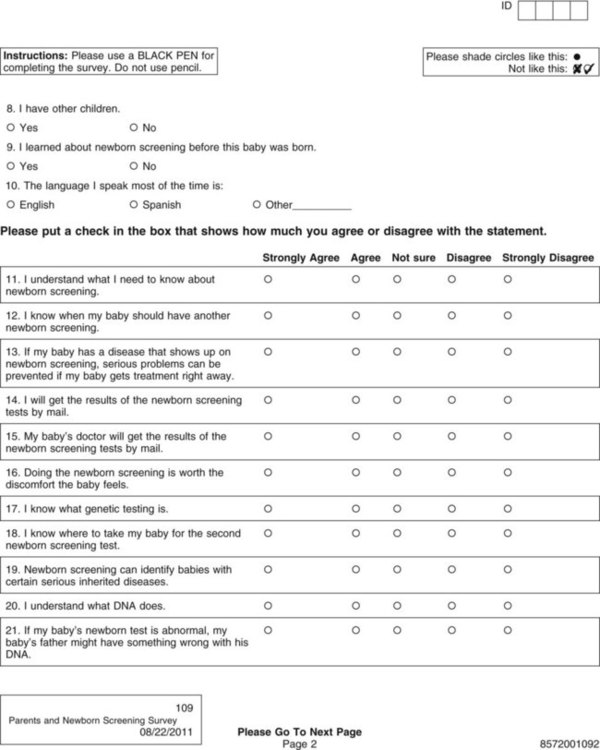

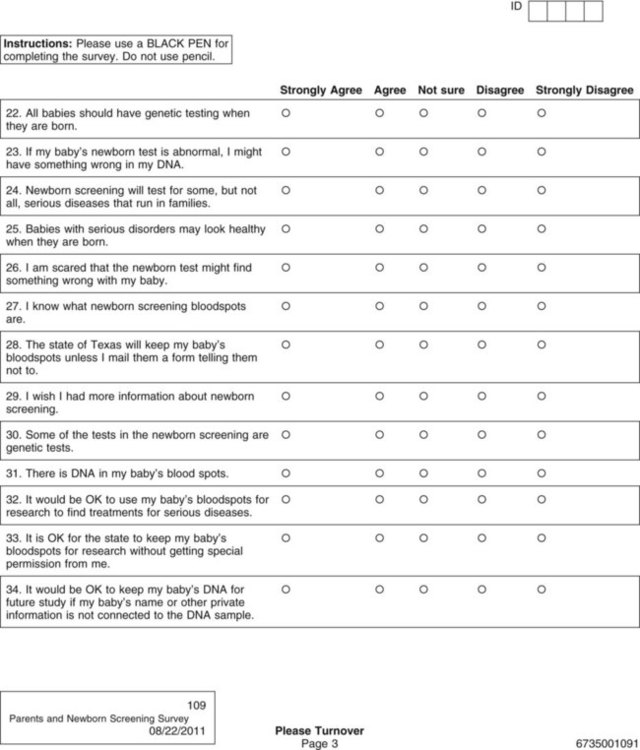

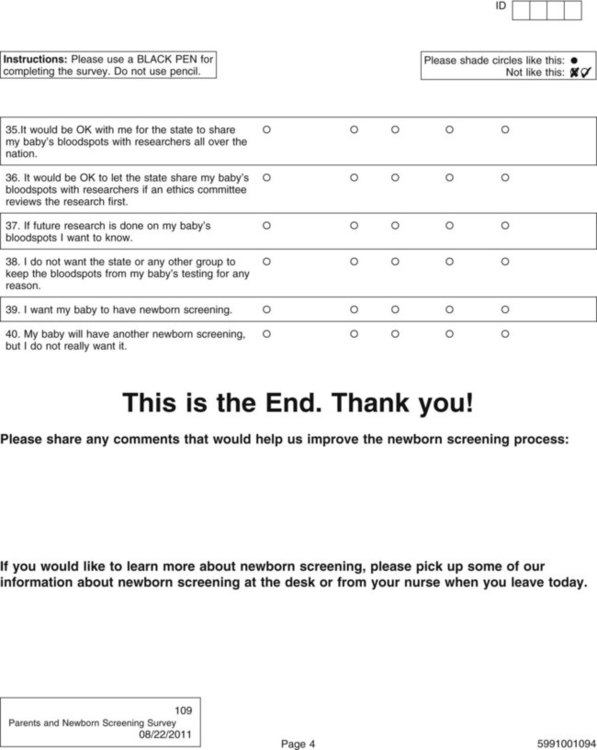

Data collection is one of the most exciting parts of research. After all the planning, writing, and negotiating, you should be eager and well prepared for this active part of research. The passion that comes from wanting to know the answer to your research question brings a sense of excitement and eagerness to start collecting your data. However, before you leap into data collection, you need to spend some time carefully planning this adventure and pilot test each step. Planning data collection begins with identifying all the data to be collected. The data to be collected are determined by the research questions, objectives, or hypotheses of the proposed study. As you develop the data collection plan, be sure that you gather all the data needed to answer the research questions, achieve the study objectives, or test the hypotheses. Chapter 16 includes detailed information about measurement, so the focus in this chapter is on the logistical and pragmatic aspects of quantitative data collection. Data collection strategies for qualitative studies are described in Chapter 12. Data can be collected by interview (face-to-face or telephone); observations; focus groups; self-administered questionnaires (online or hard copy); or extraction from existing documents such as patient medical records, motor vehicle department accident records, or state birth records (Figure 20-1). Many factors need to be considered when a researcher is deciding on the mode for collecting data. Harwood and Hutchinson (2009) describe four factors that need to be part of your decision-making process: (1) purpose and complexity of the study, (2) availability of financial and physical resources, (3) characteristics of study participants and how best to gain access to them from the population, and (4) your skills and preferences as a researcher. If the researcher is administering the survey, will it be in person or by telephone? If self-administered, will the participant complete a pencil-and-paper copy or an online electronic copy? Internet survey centers specialize in this mode of data collection and have expert help or tutorials for assessing the best mode for your study purpose. For example, in deciding on a telephone survey, how many times will you try to reach a potential subject before you give up, what days of the week or hours of the day will you call and how might that bias your sample or their responses, and how will you accurately determine the response rate (Harwood, 2009)? If you decide on a mailed paper-and-pencil survey, what will you do with undelivered or incomplete returns? Will you search for correct mailing addresses and try again? Will you send a reminder if the survey is not received within a particular time frame, and, if so, what time frame will you give a respondent, and how many reminders will you send (Harwood, 2009)? Other software allows the preparation of special data collection forms that rely on optical character recognition (OCR), which requires exact placement on the page for each potential response. To maintain the precise location of each response on print copies of these instruments, careful attention must be given to printing or copying these forms. The complete form is scanned, and the answers (data) are automatically recorded in a database. Additional features include data accuracy verification, selective data extraction and analysis, auditing and tracking, and flexible export interfaces. Figure 20-2 shows the scannable version of the Parents and Newborn Screening Survey developed by Patricia Newcomb, PhD, RN, CPNP, and Barbara True, MSN, CNS. Subjects completing the survey fill in the circle that corresponds to the appropriate option for each question. Online services can be easy to use for both the researcher and study participants but may be costly and require specific assurances about confidentiality of data and anonymity of subjects. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) supports a secure Internet environment for building online data surveys and data management packages (Harris et al., 2009). This service, developed by experts at Vanderbilt University, is called REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) and may be available at your university research site (http://project-redcap.org/). Im et al. (2007) conducted a survey in the United States of gender and ethnic differences in the experience of cancer pain. These researchers administered their questionnaire over the Internet and through a paper-and-pencil format based on subject preference. The following excerpt describes the data collection procedure for their study: Im et al. (2007) maximized their sample size and obtained a more representative sample by giving participants an option to complete their questionnaire on the Internet or using paper-and-pencil format. The researchers took steps to ensure that the data collected by the two formats were comparable by testing for significant differences and finding none. The time to complete the Internet and paper-and-pencil questionnaires did not vary. Im et al. (2007) also ensured that an ethical study was conducted and subjects’ rights were protected. The additional advantage of Internet data collection is that responses can be time/date stamped. For example, if subjects are instructed to complete the questionnaire before bedtime, the time can be verified. If subjects are instructed to complete a daily diary, date of entry would be documented, and subjects would be discouraged from entering all diary days on the last day just before returning the diary to the researcher (Fukuoka, Kamitani, Dracup, & Jong, 2011). Savian, Paratz, and Davies (2006) conducted a single-blind randomized, crossover study with 14 mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. The computerized systems used to collect and record data in the study by Savian et al. (2006) are detailed in the following excerpt: The use of computerized data collection by Savian et al. (2006) enabled them to collect repeated measures on several physiological variables in an accurate and precise way. The data were collected by sensors and stored in the computer to reduce error and facilitate data analysis. Who will collect the data? If you decide to use data collectors, they must be trained in responsible conduct of research and issues of informed consent, ethics, and confidentiality and anonymity (see Chapter 9). They must be informed about the research project, familiar with the instruments to be used, and have equivalent training in the data collection process. In addition to training, data collectors need written guidelines or protocols that indicate which instruments to use, the order in which to introduce the instruments, how to administer the instruments, and a time frame for the data collection process (Harwood, 2009; Kang, Davis, Habermann, Rice, & Broome, 2005). If more than one person is collecting the data, consistency among data collectors (interrater reliability) must be ensured through testing (see Chapter 16). The training needs to continue until interrater reliability estimates are at least 85% to 90% agreement between the expert and the trainee or trainees. Waltz, Strickland, and Lenz (2010) suggest that a minimum of 10% of the data needs to be compared across raters before interrater reliability can be adequately reported. The trained data collector’s interrater reliability with the expert trainer should be assessed intermittently throughout data collection to ensure consistency from the first to the last participant in the study. Data collectors also must be encouraged to identify and record any problems or variations in the environment that affect the data collection process. The description of the training of the data collectors is usually reported in the methods section of an article so that others can assess the data collection process (Harwood & Hutchinson, 2009). The factors of cost, time, availability of assistance, and need for consistency shape the data collection plan that you develop. A data collection plan details how you will implement your study. The plan for collecting data is specific to the study being conducted and requires that you consider some common elements of research. You need to map out procedures you will use to collect data, anticipate the time and cost of data collection, develop data collection forms that ease data entry, and prepare a codebook that will help you to code the variables to be entered in a database. This extensive planning increases the accuracy of the data collected and the validity of the study findings. The validity and strength of the findings from several carefully planned studies increase the quality of the research evidence that is then available for implementing into clinical practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2010). Identifying data include variables such as patient record number, home address, and date of birth (see Chapter 9). Avoid collecting these data unless they are essential to answer the research question. For example, collect a patient’s age instead of date of birth. Review regulations by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act about the participant’s private health information (www.hhs.gov/ocr/hipaa). Data collection forms must be designed so that the data are easily recorded, coded, and entered into the computer. You need to decide whether data will be collected in raw form or coded at the time of collection. Coding in quantitative studies is the process of transforming data into numerical symbols that can be entered easily into the computer. For example, variables such as race, gender, ethnicity, and diagnoses can be categorized and given numerical labels. For gender, the male category could be identified by a “1” and the female category by a “2.” You may also want to include an “other” category (coded “3”) for participants who are transgendered or transsexual. To be able to compare your sample with samples in federally funded studies, you may need to separate the questions about ethnicity and race. In 2003, the Office of Management and Budget of the U.S. government directed researchers and others collecting data for federal purposes or at federal expense to separate the questions of race and ethnicity (Office of Minority Health, 2010). At the same time, the Office of Management and Budget specified the categories for each. The following questions are correct according to these federal guidelines. How would a subject who is biracial or multiracial complete the form? You may want to word the question to ask the participant’s primary race or allow multiple responses.

Collecting and Managing Data

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Grove/practice/

Data Collection Modes

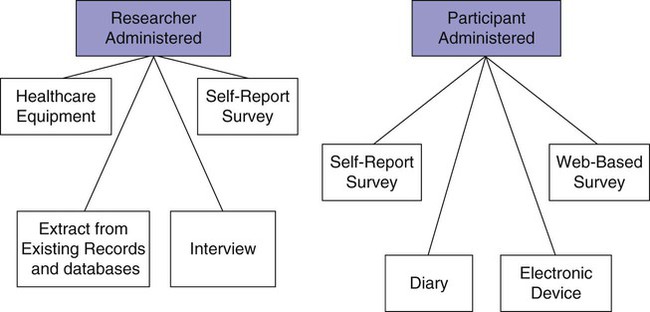

Researcher-Administered or Participant-Administered Instruments

Electronic Data Collection

Scannable Forms

Online Data Collection

Computer-Based Data Collection

Factors Influencing Data Collection

Consistency

Data Collection and Coding Plan

Data Collection Forms

Collecting and Managing Data

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access