Antipsychotics and Anxiolytics

Objectives

Key Terms

acute dystonia, p. 372

akathisia, p. 372

antiemetic, p. 371

antipsychotics, p. 371

anxiolytics, p. 380

atypical antipsychotics, p. 371

blood dyscrasias, p. 375

dopamine, p. 371

dystonia, p. 375

extrapyramidal symptoms, p. 371

neuroleptic, p. 370

neuroleptic malignant syndrome, p. 372

orthostatic hypotension, p. 373

parkinsonism, p. 371

phenothiazines, p. 372

psychosis, p. 371

schizophrenia, p. 371

tardive dyskinesia, p. 372

typical antipsychotics, p. 371

Antipsychotics and anxiolytics are CNS depressants used to manage symptoms of psychosis and anxiety disorders. Antipsychotics are also known as neuroleptics or psychotropics, but the preferred name for this group is either antipsychotics or neuroleptics. Neuroleptic refers to any drug that modifies psychotic behavior and exerts an antipsychotic effect. Anxiolytics are also called antianxiety drugs or sedative-hypnotics. Certain anxiolytics are used to treat sleep disorders, seizures, and withdrawal symptoms from alcohol or other abuse substances. Some of these drugs are also used for conscious sedation and anesthesia supplementation. However, the anxiolytics described in this chapter are used specifically to treat anxiety.

Psychosis

Psychosis, or losing contact with reality, is manifested in a variety of mental or psychiatric disorders. Psychosis is usually characterized by more than one symptom, but these may include difficulty in processing information and coming to a conclusion, delusions, hallucinations, incoherence, catatonia, and aggressive or violent behavior. Schizophrenia, a chronic psychotic disorder, is the major category of psychosis in which many of these symptoms are manifested.

The symptoms of schizophrenia usually develop in adolescence or early adulthood. The symptoms of this psychotic disorder are divided into two groups: “positive” symptoms and “negative” symptoms. Positive symptoms may be characterized by exaggeration of normal function (e.g., agitation), incoherent speech, hallucinations, delusions, and paranoia. Negative symptoms are characterized by a decrease or loss in function and motivation. There is a poverty of speech content, poor self-care, and social withdrawal. Negative symptoms tend to be more chronic and persistent. The typical or traditional group of antipsychotics is more helpful for managing positive symptoms than negative symptoms. A group of antipsychotics called atypical have been found to be more useful in treating both the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Antipsychotics compose the largest group of drugs used to treat mental illness. Specifically, these drugs improve the thought processes and behavior of patients with psychotic symptoms, especially those with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. They are not used to treat anxiety or depression. The theory is that psychotic symptoms result from an imbalance in the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain. Sometimes these antipsychotics are called dopamine antagonists. Antipsychotics block D2 dopamine receptors in the brain, reducing psychotic symptoms. Many antipsychotics block the chemoreceptor trigger zone and vomiting (emetic) center in the brain, producing an antiemetic (prevents or relieves nausea and vomiting) effect. When dopamine is blocked, however, extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) of parkinsonism (Parkinson’s disease, a chronic neurologic disorder that affects the extrapyramidal motor tract) such as tremors, masklike facies, rigidity, and shuffling gait may develop. Many patients who take high-potency antipsychotic drugs may require long-term medication for parkinsonian symptoms.

Antipsychotic Agents

Antipsychotics are divided into two major categories: typical (or traditional) and atypical. The typical antipsychotics, introduced in 1952, are subdivided into phenothiazines and nonphenothiazines. Nonphenothiazines include butyrophenones, dibenzoxazepines, dihydroindolones, and thioxanthenes. The phenothiazines and thioxanthenes block norepinephrine, causing sedative and hypotensive effects early in treatment. The butyrophenones block only the neurotransmitter dopamine.

Atypical antipsychotics make up the second category of antipsychotics. Clozapine, discovered in the 1960s and made available in Europe in 1971, was the first atypical antipsychotic agent. It was not marketed in the United States until 1990 because of adverse hematologic reactions. Atypical antipsychotics are effective for treating schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in patients who do not respond to or are intolerant of typical antipsychotics. Because of their decreased side effects, atypical antipsychotics are often used instead of traditional typical antipsychotics as first-line therapy.

Pharmacophysiologic Mechanisms of Action

Antipsychotics block the actions of dopamine and thus may be classified as dopaminergic antagonists. There are five subtypes of dopamine receptors: D1 through D5. All antipsychotics block the D2 (dopaminergic) receptor, which in turn promotes the presence of EPS, resulting in drug-induced pseudoparkinsonism in varying degrees. Atypical antipsychotics have a weak affinity to D2 receptors, a stronger affinity to D4 receptors, and they block the serotonin receptor. These agents cause fewer EPS than the typical (phenothiazines) antipsychotic agents, which have a strong affinity to D2 receptors.

Adverse Reactions

Extrapyramidal Syndrome

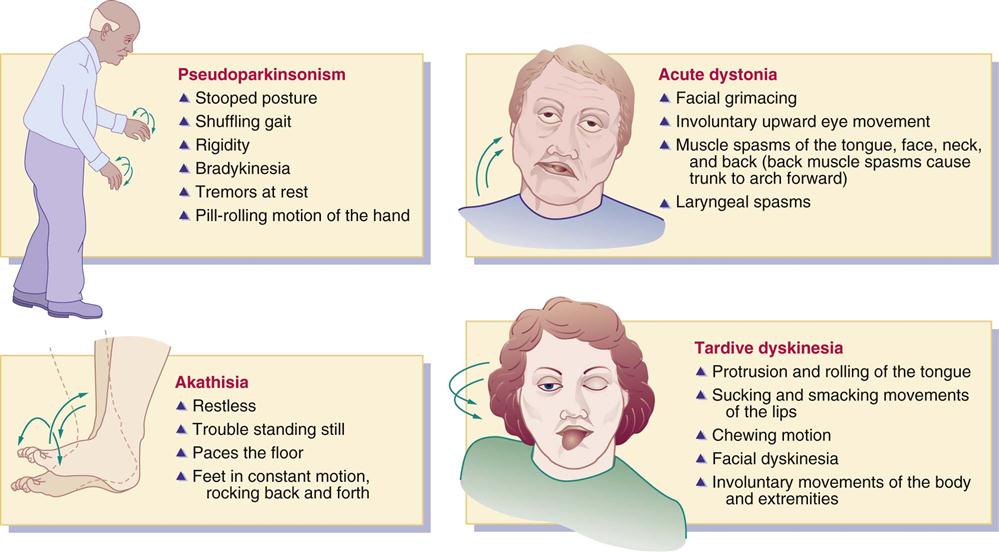

Pseudoparkinsonism, which resembles symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, is a major side effect of typical antipsychotic drugs. Symptoms of pseudoparkinsonism, or EPS, include stooped posture, masklike facies, rigidity, tremors at rest, shuffling gait, pill-rolling motion of the hand, and bradykinesia. When patients take high-potency typical antipsychotic drugs, these symptoms are more pronounced. Patients who take low-strength antipsychotics such as chlorpromazine (Thorazine) are not as likely to have symptoms of pseudoparkinsonism as those who take fluphenazine (Prolixin).

During early treatment with typical antipsychotic agents for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, two adverse extrapyramidal reactions that may occur are acute dystonia and akathisia. Tardive dyskinesia is a later phase of extrapyramidal reaction to antipsychotics. Use of anticholinergic drugs helps decrease pseudoparkinsonism symptoms, acute dystonia, and akathisia, but has little effect on alleviating tardive dyskinesia.

The symptoms of acute dystonia usually occur in 5% of patients within days of taking typical antipsychotics. Characteristics of the reaction include muscle spasms of the face, tongue, neck, and back; facial grimacing; abnormal or involuntary upward eye movement; and laryngeal spasms that can impair respiration. This condition is treated with anticholinergic/antiparkinsonism drugs such as benztropine (Cogentin). The benzodiazepine lorazepam (Ativan) may also be prescribed.

Akathisia occurs in approximately 20% of patients who take a typical antipsychotic drug. With this reaction, the patient has trouble standing still, is restless, paces the floor, and is in constant motion (e.g., rocks back and forth). Akathisia is best treated with a benzodiazepine (e.g., lorazepam) or a beta blocker (e.g., propranolol).

Tardive dyskinesia is a serious adverse reaction occurring in approximately 20% to 30% of patients who have taken a typical antipsychotic drug for more than 1 year. The prevalence is higher in cigarette smokers. The likelihood of developing tardive dyskinesia depends on the dose and duration of the antipsychotic factor. Characteristics of tardive dyskinesia include protrusion and rolling of the tongue, sucking and smacking movements of the lips, chewing motion, and involuntary movement of the body and extremities. In older adults, these reactions are more frequent and severe. The antipsychotic drug should be stopped in all who experience tardive dyskinesia and another antipsychotic agent substituted. Benzodiazepines, calcium channel blockers, or beta blockers are helpful in some cases in decreasing tardive dyskinesia. No one agent is effective for all patients. High doses of vitamin E may be helpful, and its use to treat tardive dyskinesia is currently under investigation. Clozapine (Clozaril) has also been effective for treating tardive dyskinesia. Tetrabenazine (Xenazine), used to improve symptoms of Huntington’s disease, seems to be effective in treating tardive dyskinesia. Tetrabenazine reduces dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin levels. Amantadine has also been helpful in reducing drug-induced involuntary movements. Figure 27-1 shows the characteristics of pseudoparkinsonism, acute dystonia, akathisia, and tardive dyskinesia.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare but potentially fatal condition associated with antipsychotic drugs. Predisposing factors include excess agitation, exhaustion, and dehydration. NMS symptoms involve muscle rigidity, sudden high fever, altered mental status, blood pressure fluctuations, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, seizures, rhabdomyolysis, acute renal failure, respiratory failure, and coma. Treatment of NMS involves immediate withdrawal of antipsychotics, adequate hydration, hypothermic blankets, and administration of antipyretics, benzodiazepines, and muscle relaxants such as dantrolene (Dantrium).

Phenothiazines

Chlorpromazine hydrochloride (Thorazine) was the first phenothiazine introduced for treating psychotic behavior in patients in psychiatric hospitals. The phenothiazines are subdivided into three groups: aliphatic, piperazine, and piperidine, which differ mostly in their side effects.

The aliphatic phenothiazines produce a strong sedative effect, decreased blood pressure, and may cause moderate EPS (pseudoparkinsonism). Chlorpromazine hydrochloride is in the aliphatic group and may produce pronounced orthostatic hypotension (low blood pressure that occurs when an individual assumes an upright position from a supine position).

The piperazine phenothiazines produce more EPS than other phenothiazines. They cause dry mouth, urinary retention, and agranulocytosis. Examples of piperazine phenothiazines are fluphenazine (Prolixin) and perphenazine (Trilafon).

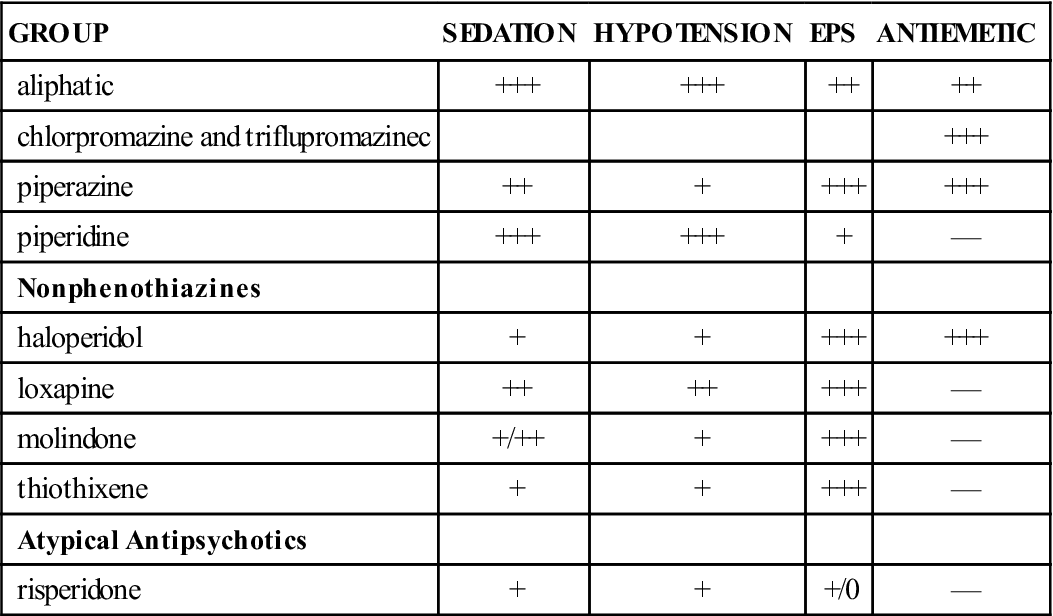

The piperidine phenothiazines have a strong sedative effect, cause few EPS, have a low to moderate effect on blood pressure, and have no antiemetic effect. Thioridazine (Mellaril) is an example of piperidine phenothiazines. Table 27-1 summarizes the effects of the phenothiazines.

TABLE 27-1

EFFECTS OF PHENOTHIAZINES (VARIES WITHIN CLASS)

| GROUP | SEDATION | HYPOTENSION | EPS | ANTIEMETIC |

| aliphatic | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ |

| chlorpromazine and triflupromazinec | +++ | |||

| piperazine | ++ | + | +++ | +++ |

| piperidine | +++ | +++ | + | — |

| Nonphenothiazines | ||||

| haloperidol | + | + | +++ | +++ |

| loxapine | ++ | ++ | +++ | — |

| molindone | +/++ | + | +++ | — |

| thiothixene | + | + | +++ | — |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | ||||

| risperidone | + | + | +/0 | — |

—, No effect; +, mild effect; ++, moderate effect; +++, severe effect; EPS, extrapyramidal symptoms.

Most antipsychotics can be given orally (tablet or liquid), intramuscularly (IM), or intravenously (IV). For oral use, the liquid form might be preferred, because some patients hide tablets to avoid taking them. In addition, the absorption rate is faster with the liquid form. Peak serum drug level occurs in 2 to 3 hours. The antipsychotics are highly protein bound (>90%), and excretion of the drugs and their metabolites is slow. Phenothiazines are metabolized by liver enzymes into phenothiazine metabolites. Metabolites can be detected in the urine several months after the medication has been discontinued. Phenothiazine metabolites may cause a harmless pinkish to red-brown urine color. The full therapeutic effects of antipsychotics may not be evident for 3 to 6 weeks following initiation of therapy, but an observable therapeutic response may be apparent after 7 to 10 days.

Noncompliance with antipsychotics is common. Encourage the patient to take the medication as prescribed. Explain and emphasize essential information to compensate for patients’ knowledge deficit, and provide an interpreter for patients whose first language is not English.

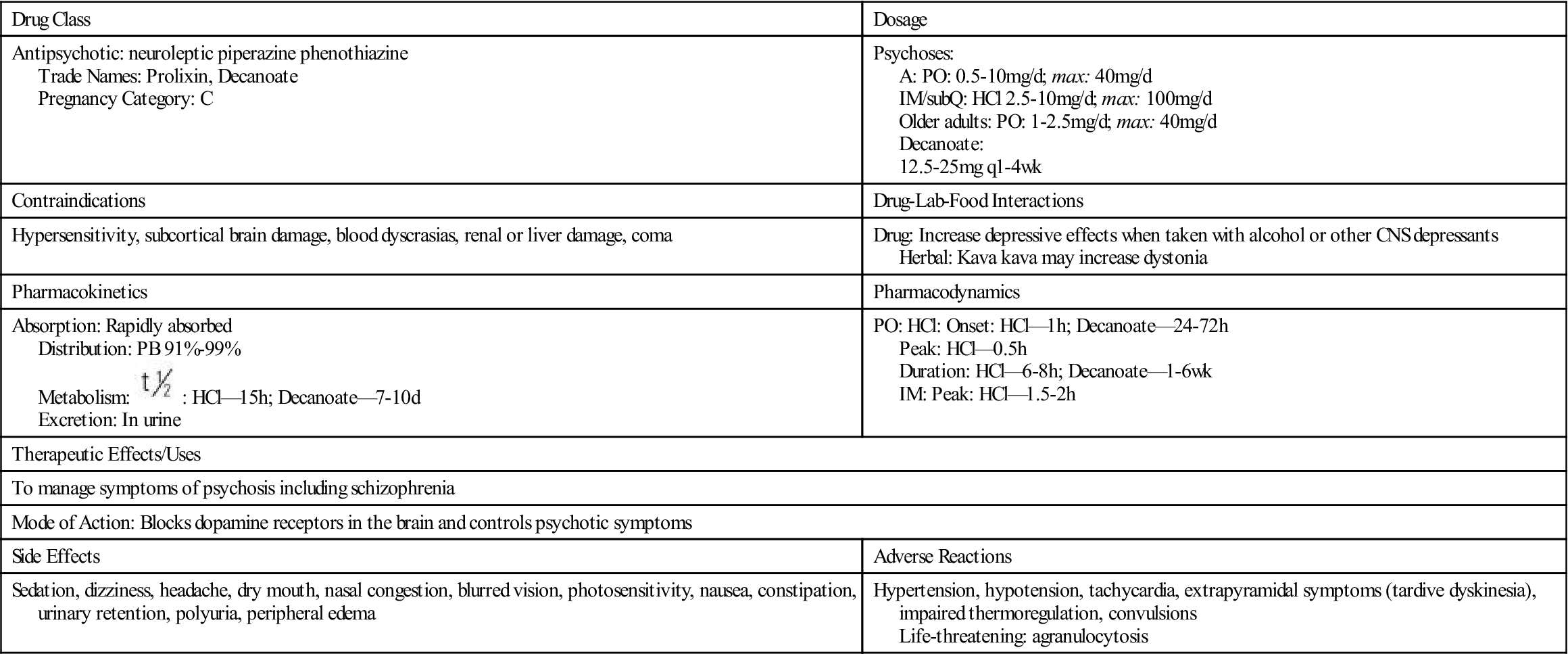

Prototype Drug Chart 27-1 shows the drug characteristics of fluphenazine (Prolixin), a phenothiazine antipsychotic used to manage psychosis. Box 27-1 shows the symptoms and suggested treatment for overdose of phenothiazines.

Pharmacokinetics

Oral absorption of fluphenazine is rapid and not affected by food. This drug is strongly protein-bound and has a long half-life; therefore, the drug may accumulate. Fluphenazine is metabolized by the liver, crosses the blood-brain barrier and placenta, and is excreted as metabolites primarily in the urine. With hepatic dysfunction, the phenothiazine dose may need to be decreased. Lack of drug metabolism in the liver will cause an elevation in serum drug level.

Pharmacodynamics

Fluphenazine is prescribed primarily for psychotic disorders. This drug has anticholinergic properties and should be cautiously administered to patients with glaucoma, especially narrow-angle glaucoma. Because hypotension is a side effect of these phenothiazines, any antihypertensives simultaneously administered can cause an additive hypotensive effect. Narcotics and sedative-hypnotics administered simultaneously with these phenothiazines can cause an additive CNS depression. Antacids decrease the absorption rate of both drugs and all phenothiazines, so they should be given 1 hour before or 2 hours after an oral phenothiazine.

The onset of action for fluphenazine hydrochloride is 1 hour, with a duration rate of 6 to 8 hours. Fluphenazine decanoate has delayed absorption, with an onset of action of 24 to 72 hours and a duration of 1 to 6 weeks.

Nonphenothiazines

The many groups of nonphenothiazine antipsychotics include butyrophenone, dibenzoxazepines, dihydroindolone, and thioxanthene.

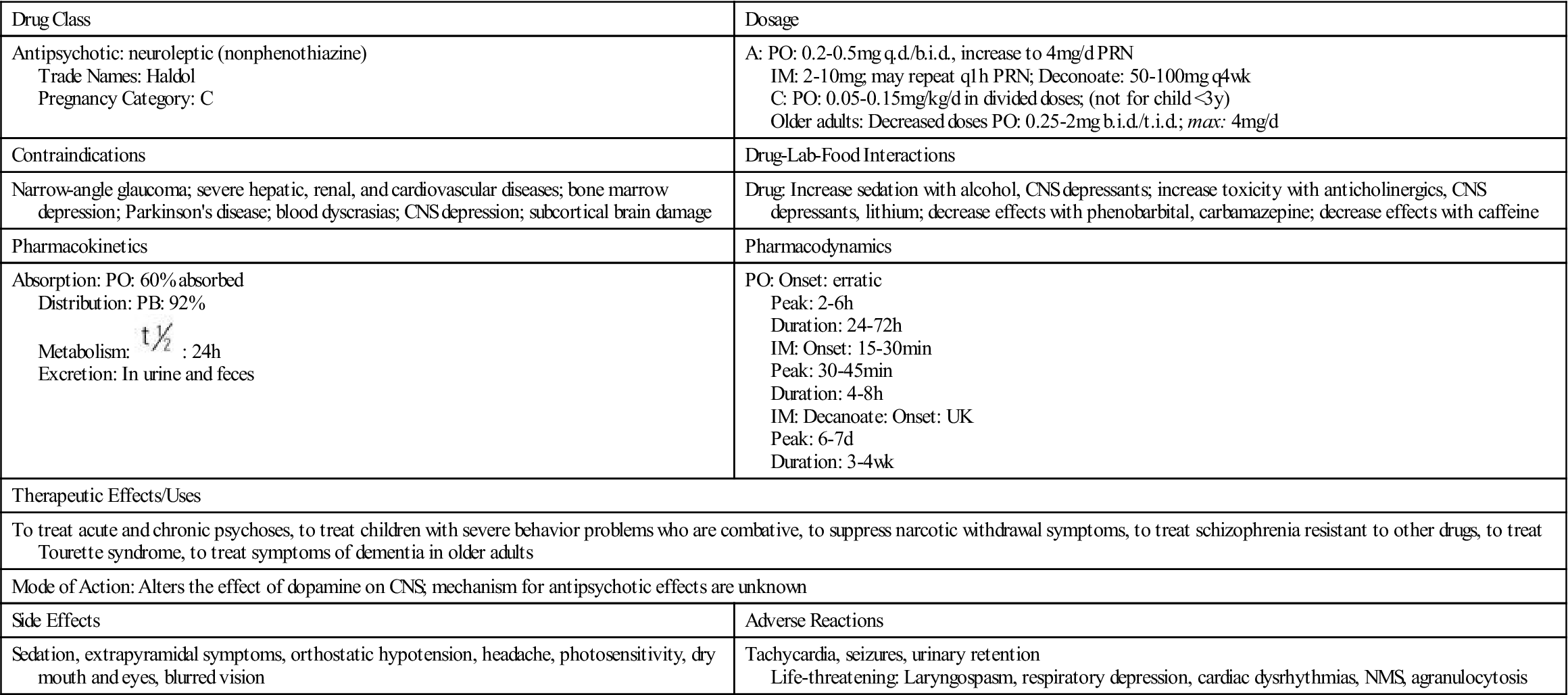

In the butyrophenone group, a frequently prescribed nonphenothiazine is haloperidol (Haldol). Haloperidol’s pharmacologic behavior is similar to that of the phenothiazines. It is a potent antipsychotic drug in which the equivalent prescribed dose is smaller than drugs of lower potency (e.g., chlorpromazine). The drug dose for haloperidol is 0.5 to 5 mg, whereas the drug dose for chlorpromazine is 10 to 25 mg. Long-acting preparations (haloperidol decanoate [Haldol] and fluphenazine decanoate [Prolixin]) are given for slow release via injection every 2 to 4 weeks. Administration precautions should be taken to prevent soreness and inflammation at the injection site. Because the medication is a viscous liquid, a large-gauge needle (e.g., 21-gauge) should be used with the Z-track method for administration in a deep muscle. See Chapter 4 for further explanation of the Z-track method of injection. The injection site should not be massaged, and sites should be rotated. These medications should not remain in a plastic syringe longer than 15 minutes. Prototype Drug Chart 27-2 provides the drug data related to haloperidol.

Pharmacokinetics

Haloperidol is absorbed well through the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa. It has a long half-life and is highly protein-bound, so the drug may accumulate. Haloperidol is metabolized in the liver and excreted in urine and feces.

Pharmacodynamics

Haloperidol alters the effects of dopamine by blocking dopamine receptors; thus sedation and EPS may occur. The drug is used to control psychoses and decrease agitation in adults and children. Dosages need to be decreased in older adults because of decreased liver function and potential side effects. It may be prescribed for children with hyperactive behavior. Haloperidol has anticholinergic activity, so care should be taken when administering it to patients with a history of glaucoma.

Haloperidol has a similar onset of action, peak time of concentration, and duration of action as phenothiazines. It has strong EPS effects. Skin protection is necessary for prolonged use because of the possible side effect of photosensitivity.

From the dibenzoxazepine group, loxapine (Loxitane) is a moderately potent agent. It has moderate sedative and orthostatic hypotensive effects and a strong EPS effect.

The typical antipsychotic molindone hydrochloric acid (Moban) from the dihydroindolone group is a moderately potent agent. It has low sedative and orthostatic hypotensive effects and a strong EPS effect.

In the nonphenothiazine group known as thioxanthenes is thiothixene (Navane), a highly potent typical antipsychotic drug. It has side effects similar to those of molindone with low sedative and orthostatic hypotensive effects and a strong EPS effect.

Side Effects and Adverse Reactions

Several side effects are associated with antipsychotics. The most common side effect for all antipsychotics is drowsiness. Many of the antipsychotics have some anticholinergic effects: dry mouth, increased heart rate, urinary retention, and constipation. Blood pressure decreases with the use of antipsychotics; aliphatics and piperidines cause a greater decrease in blood pressure than the others.

EPS can begin within 5 to 30 days after initiation of antipsychotic therapy and are most prevalent with the phenothiazines, butyrophenones, and thioxanthenes. These symptoms include pseudoparkinsonism, akathisia, dystonia (prolonged muscle contractions with twisting, repetitive movements), and tardive dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia may develop in 20% of patients taking antipsychotics for long-term therapy. Antiparkinsonian anticholinergic drugs may be given to control EPS, but they are not always effective in treating tardive dyskinesia.

High dosing or long-term use of some antipsychotics can cause blood dyscrasias (blood cell disorders) such as agranulocytosis. White blood cell (WBC) count should be closely monitored and reported to the health care provider if there is an extreme decrease in leukocytes.

Dermatologic side effects seen early in drug therapy are pruritus and marked photosensitivity. Patients are urged to use sunscreen, hats, and protective clothing and to stay out of the sun.

Drug Interactions

Because phenothiazine lowers the seizure threshold, dosage adjustment of an anticonvulsant may be necessary. If either aliphatic phenothiazine or the thioxanthene group is administered, a higher dose of anticonvulsant might be necessary to prevent seizures.

Antipsychotics interact with alcohol, hypnotics, sedatives, narcotics, and benzodiazepines to potentiate the sedative effects of antipsychotics. Atropine counteracts EPS and potentiates antipsychotic effects. Use of antihypertensives can cause an additive hypotensive effect.

Antipsychotics should not be given with other antipsychotic or antidepressant drugs except to control psychotic behavior for selected individuals who are refractory to drug therapy. Under ordinary circumstances, if one antipsychotic drug is ineffective, a different one is prescribed. Individuals should not take alcohol or other CNS depressants (e.g., narcotic analgesics, barbiturates) with antipsychotics, because additive depression is likely to occur.

When discontinuing antipsychotics, the drug dosage should be reduced gradually to avoid sudden recurrence of psychotic symptoms. Table 27-2 lists common antipsychotic drugs (phenothiazines and nonphenothiazines) and their dosages, uses, and considerations.

TABLE 27-2

PHENOTHIAZINES AND NONPHENOTHIAZINES

| GENERIC (BRAND) | DRUG POTENCY | ROUTE AND DOSAGE | USES AND CONSIDERATIONS |

| Phenothiazines | |||

| Aliphatics | |||

| chlorpromazine HCl (Thorazine) | Low | A: PO: 25-100 mg t.i.d./q.i.d. A: IM/IV: 25-50 mg q4-6h C >6 mo: PO: 0.55 mg/kg q4-6h C >6 mo: IM/IV: 0.5-1 mg/kg q6-8h | For psychosis, schizophrenia, intractable hiccups, preoperative sedation, behavioral problems in children, nausea, and vomiting. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 95%;  : 24 h : 24 h |

| Piperazines | |||

| fluphenazine HCl (Prolixin) | High | See Prototype Drug Chart 27-1. | |

| perphenazine (Trilafon) | Moderate | A: PO: 4-16 mg b.i.d./t.i.d./q.i.d.; max: 64 mg/d | For psychotic disorders; to control severe nausea and vomiting; to treat intractable hiccups. Used also before chemotherapy to prevent nausea. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 91%-97%;  : 9-12 h : 9-12 h |

| Piperidines | |||

| thioridazine HCl (Mellaril)* | Low | A: PO: 50-100 mg t.i.d.; max: 300 mg/d Older adults: 10 mg t.i.d.; max: 300 mg/d C 2-12 y: PO: 0.5-3 mg/kg/d in 2-3 divided doses; max: 3 mg/kg/d | For psychosis only when unresponsive to other medications. Higher doses for severe psychosis. Lower doses (10-50 mg t.i.d.) for marked depression, alcohol withdrawal, intractable pain. Few EPS. Little antiemetic effect. Can cause life-threatening dysrhythmias. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 91%-99%;  : 24-34 h : 24-34 h |

| Nonphenothiazines | |||

| Butyrophenone | |||

| haloperidol (Haldol) | High | See Prototype Drug Chart 27-2. | |

| Dibenzoxazepine | |||

| loxapine (Loxitane) | Moderate | A: PO: Initially 10-25 mg q12h; maintenance 60-100 mg/d in divided doses; max: 250 mg/d Older adults: 5-10 mg daily/b.i.d.; maintenance 40-50 mg/d; max: 250 mg/d | For acute psychosis and schizophrenia. Likely to cause EPS. Overdose can cause cardiac toxicity or neurotoxicity. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 95%;  : 8 h : 8 h |

| Dihydroindolone | |||

| molindone HCl (Moban) | Moderate | A: PO: Initial: 50-75 mg in 3-4 divided doses, then 15-50 mg t.i.d./q.i.d.; max: 225 mg/d Older adults:  – – adult dose adult dose | Management of schizophrenia. Can cause EPS. Has less sedative effect. Pregnancy category: C; PB: UK;  : 1.5 h : 1.5 h |

| Thioxanthenes | |||

| thiothixene HCl (Navane) | High | A: PO: 2 mg t.i.d.; max: 60 mg/d | Management of psychotic disorders, especially acute and chronic schizophrenia. Can cause EPS. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 90%;  : 34 h : 34 h |

| Atypical Antipsychotics | |||

| clozapine (Clozaril) | Low | A: PO: Initially: 12.5 mg/d or b.i.d.; if tolerated, gradually increase to 300-450 mg/d in 3 divided doses; max: 900 mg/d | For severely ill schizophrenic patients, especially those who do not respond to other antipsychotics. With long-term use, monitor white blood cell count. Pregnancy category: B; PB: 95%;  : 8-12 h : 8-12 h |

| olanzapine (Zyprexa Zydis) Extended-release injectable (Zyprexa Relprevv) | UK | A: IM: 5-10 mg/d; max: 20 mg/d Older adults: PO: 5 mg q.d.; max: 20 mg/d A: IM: IR: 5-10 mg/d Older adults: IM: 2.5-5 mg/d A: IM: ER: 150-300 mg q2wk or 405 mg q4wk Older adults: IM: ER: 150 q4wk | Treatment of schizophrenia. Does not cause EPS. May cause headaches, dizziness, excess weight gain, agitation, insomnia, and somnolence. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 93%;  : 21-54 h : 21-54 h |

| quetiapine (Seroquel) | UK | A: PO: Initially 25 mg/b.i.d.; increase 25-50 mg b.i.d./t.i.d. first week up to 300-400 mg/d in 2-3 divided doses; max: 800 mg/d Older adults: PO: 25 mg b.i.d.; increase q.d.; max: 400 mg/d A: XR: 300 mg h.s.; max: 800 mg/d Older adults: XR: 50 mg/d, increase 50 mg/d; max: 200-800 mg/d | Treatment of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. Not likely to cause EPS. May cause dizziness, headache, sedation. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 83%;  : 6 h : 6 h |

| asenapine (Saphris) | UK | A: SL: 5-10 mg b.i.d.; max: 20 mg/d | For treatment of schizophrenia and manic bipolar disorder. Adverse effects include dizziness, appetite stimulation, dysrhythmias, and pseudoparkinsonism. Pregnancy category: C; PB: UK;  : 24 h : 24 h |

| risperidone (Risperdal) | Low | Psychosis: A: PO: Initially 2 mg/d, increase to 4-8 mg/d Older adults: PO: Initially 0.5-1.5 mg b.i.d.; max: 4 mg/d Adol: PO: Initially 0.5 mg q.d., increase up to 3 mg/d | For management of schizophrenia. May cause sedation, headaches, sexual dysfunction, hyperglycemia, EPS, and NMS. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 90%;  : 24 h : 24 h |

| ziprasidone (Geodon) | UK | A: PO: 20 mg b.i.d. may increase q2d; max: 160 mg/d A: IM: 10 mg q2h or 20 mg q4h; max: 40 mg/d | For management of schizophrenia. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 99%;  : 7 h : 7 h |

| iloperidone (Fanapt) | UK | A: PO: Initially 1 mg b.i.d., then 6-12 mg b.i.d.; max: 24 mg/d | For treatment of schizophrenia. Adverse effects include GI distress, blurred vision, confusion, dehydration, dysrhythmias, and pseudoparkinsonism. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 95%;  : 18-33 h : 18-33 h |

| aripiprazole (Abilify) | UK | See Prototype Drug Chart 27-3. | |

| paliperidone (Invega, Invega Sustenna) | UK | A: PO: 6-12 mg/d in the AM; max: 12 mg/d A: IM: ER: 39-234 mg/mo | Treatment of schizophrenia. Extended-release injectable is given once a month. Pregnancy category: C; PB: 74%;  : 23 h : 23 h |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

: HCl—15 h; Decanoate—7-10 d

: HCl—15 h; Decanoate—7-10 d

, half-life; wk, week.

, half-life; wk, week. : 24 h

: 24 h

, half-life; t.i.d., three times a day; UK, unknown; wk, week; y, year; <, less than.

, half-life; t.i.d., three times a day; UK, unknown; wk, week; y, year; <, less than.