Recurrence Rate

High rates of pressure ulcer recurrence also have been reported, ranging from 21% to 79% regardless of treatment.16,17 Epidemiological studies have found that 36% to 50% of all patients with SCI who develop pressure ulcers will develop a recurrence within the first year after initial healing.7,14,16–18 Niazi et al.16 reported a recurrence rate of 35% regardless of the type of treatment (medical or surgical) provided. Holmes et al.19 found that 55% of their sample, most of whom had a history of severe previous ulcers, experienced a recurrence within 2 years after surgical repair. In a 20-year study in Canada (1976 to 1996), Schryvers et al.20 studied 168 SCI patients admitted 415 times for treatment of 598 severe recurring pressure ulcers. Of these ulcer recurrences, 31% (185) occurred at the same site as the previous ulcer and 21% (125 ulcers) occurred at a different site. Goodman et al.21 observed a recurrence or new ulcer development rate of 79% within a 1- to 6-year follow-up time frame.

Some investigators found that pressure ulcer history is a more viable measure of pressure ulcer outcome than measures taken at any single point in time over a brief period. Other studies reveal the protective mechanisms against pressure ulcer recurrence. For example, Krause and Broderick22 reported that 13% of their sample of 633 subjects had recurring pressure ulcers (one or more per year) over a 5-year period. Their findings suggested that lifestyle, exercise, and diet were protective mechanisms against pressure ulcer recurrence.

Pressure ulcer recurrence in the person with an SCI has been associated with gender (male), age (older), ethnicity (African American), unemployment, residence in a nursing home, and previous pressure ulcer surgery.22,23 Most of the literature describing recurrence following surgery focuses on surgical techniques.24–28 Investigators have reported recurrence rates of 11% to 29% in patients with postoperative complications and 6% to 61% in patients without postoperative complications.24–30 Relander and Palmer28 recommended that social factors be studied to determine the causes of pressure ulcer recurrence after surgical repair and suggested that patients who don’t display the appropriate knowledge regarding pressure ulcer prevention should be counseled before consideration for surgery. Disa et al.24 reported that high recurrence rates among patients with traumatic paraplegia were associated with substance abuse and the absence of an adequate social support system. They suggested developing more effective educational programs for both patients and caregivers.24 In other studies, Mandrekas and Mastorakos29 and Rubayi et al.30 reported that inadequate patient education with regard to pressure ulcer prevention contributed to the recurrence rates.

Recurrence also is a significant problem for veterans with SCI. Guihan et al.31 reported that there are four significant predictors of pressure ulcer recurrence in veterans. They are race (being black), more comorbidities indicating a higher burden of illness, Salzburg Pressure Ulcer (PrU) Risk Assessment Scale score (which measures 15 items associated with SCI, cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, albumin and hematocrit, and impaired cognition), and longer sitting time at discharge from the hospital following the treatment of a pressure ulcer.31

Financial Concerns

The financial burden of pressure ulcers is undoubtedly immense, although estimates of the cost of preventing and treating pressure ulcers in the patient with an SCI are not readily available. In 1994, Miller and DeLozier32 reported that the total cost of treating stage II, III, and IV pressure ulcers in hospitals, nursing homes, and home care was approximately $1.335 billion per year. One could extrapolate from these data the financial implications of pressure ulcers for patients with SCI. However, the financial burden does not begin to reflect the personal and social costs experienced by patients and their families. These include loss of independence and self-esteem; time away from work, school, or family; and, ultimately, diminished quality of life. It is well documented that the development of pressure ulcers increases both hospital costs and length of stay for all patients.33

Throughout their lifetime, persons with SCI are at risk for the development of pressure ulcers. Most of the reported costs deal with investigations of various treatment interventions, especially dressings.34 In 2003, Garber and Rintala35 reported that of 102 veterans’ charts reviewed, a total of 625 visits were made to treat 400 pressure ulcers at a cost of $250 per outpatient visit (approximate costs from 199836; costs are higher now). Stage IV was the most prevalent pressure ulcer seen, and pelvic ulcers accounted for almost two-thirds of the worst ulcers reported. The average number of clinic or home visits for pressure ulcer treatment was more than six per person. More than half of the study sample was admitted to the hospital for pressure ulcer treatment at least once during the study period. The average number of hospital admissions was two; almost 30% of veterans were admitted three times or more.35

Two recent reports have examined the direct costs of the treatment of pressure ulcers in persons with SCI. Chan et al.37 studied the costs of treating chronic pressure ulcers among community-dwelling SCI individuals in Ontario, Canada. The average monthly cost was found to be $4,745 per community-dwelling SCI individual. Costs for hospital admission were found to make up for the largest percentage of the total costs.37 In 2011, Stroupe et al. studied the costs of treating pressure ulcers among veterans with SCI.38 The total inpatient cost per year for SCI veterans with pressure ulcers was $91,341, while that for a veteran without pressure ulcer was $13,754. The total outpatient cost per year for SCI veterans with pressure ulcers was $19,844, compared to $11,829 for those without a pressure ulcer.38

Total healthcare costs for individuals with SCI are higher than other groups at risk for pressure ulcer development and increasing rapidly.39 The additional costs of treating veterans with SCI who have pressure ulcers have been estimated to be over $73,000 per annum due primarily to higher inpatient costs.38

Risk Factors

More than 200 risk factors for the development of pressure ulcers have been reported in the literature. Most of the risk factors were derived from studying elderly nursing home residents. However, many of the risk factors for these patients differ from those experienced by patients with SCI. Immobility increases the risk of pressure ulcer development in both populations. Unlike nursing home residents, however, patients with SCI are encouraged to oversee or direct their own daily care and are expected to take primary responsibility for pressure ulcer prevention. As a result of the limitations imposed by the variables among studies, the literature is often contradictory regarding the effects of a particular risk factor or set of factors potentially responsible for the development of pressure ulcers. Different populations (e.g., acute or chronic SCI patients), inadequate sample sizes, different ways of standardizing the dependent measures, and poor or uncontrolled study designs all add confusion to the interpretation of study results.40,41

According to Chen et al., the risk of pressure ulcers seems to be steady in the first 10 years but increases 15 years postinjury.11 Males, the elderly, blacks, singles, individuals who have less than a high school education, the unemployed, persons with complete SCI, and those with a history of pressure ulcers, rehospitalization, nursing home stay, and other medical comorbidities are at greater risk of developing pressure ulcers.11 Although the number of days hospitalized and frequency of rehospitalizations decreased, the number of pressure ulcers increased over time.11 Charlifue et al.8 found that although the number of pressure ulcers increased as time passed, the best predictor of pressure ulcers over time was a previous history of pressure ulcers.

Despite these limitations, a number of pressure ulcer risk factors specific to the patient with SCI have been identified and described in the literature. Byrne and Salzberg40 summarized the major pressure ulcer risk factors for the patient with an SCI as follows:

- Severity of the SCI (immobility, completeness of the injury, urinary incontinence, and severe spasticity)

- Preexisting conditions (advanced age, smoking, lung and cardiac disease, diabetes and renal disease, and impaired cognition)

- Residence in a nursing home

- Malnutrition and anemia

Characteristics associated with better pressure ulcer outcomes include maintaining normal weight, returning to work and family roles, and not smoking or having a history of tobacco use, suicidal behavior, incarceration, or alcohol or drug abuse.42 The Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines (“Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Treatment Following Spinal Cord Injury: a clinical practice guideline for health-care professionals”)6 categorized pressure ulcer risk factors in patients with SCI as follows:

- Demographic factors (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, and education)

- Physical, medical, and SCI-related factors (level and completeness of the injury; activity and mobility; nutrition, bladder, bowel, and moisture control; and comorbidities, such as diabetes and spasticity)

- Psychological and social factors (psychological distress, financial problems, cognition, substance abuse, adherence to recommended prevention behaviors/strategies, context and health beliefs and practices)

- Support surfaces for bed and wheelchair

As far back as 1979, Anderson and Andberg43 identified psychological factors associated with the development of pressure ulcers, including the patient’s unwillingness to take responsibility for his or her skin care, low self-esteem, and dissatisfaction with life activities. Gordon et al.44 also found poor social adjustment in the patient with an SCI and a pressure ulcer. The revised edition of the Paralyzed Veteran’s Association (PVA) The Consortium for Spinal Cord Injury Clinical Practice Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers in Persons with SCI6 lists the following psychological and cognitive risk factors:

- Psychological factors: Depression, anxiety, negative self-concept, poorly managed anger, and frustration may interfere with cooperation between individual and his/her care providers and may be associated with inactivity, self-neglect, and poor medical adherence.45

- Cognitive impairment: Associated traumatic brain injury and illegal drug use may interfere with cognitive function.46

Social, environmental, contextual, and circumstance factors: In recent years, there have been attempts to identify risk factors, other than obvious medical and SCI-related ones, within a person’s life that contribute to the development of pressure ulcers, interfere with healing, and fail to prevent recurrence. Homelessness, gang membership, financial problems, and lack of social support have been shown to cause frequent disruptions, promote participation in high-risk activities, and may put the person in a state of danger. The lack of access to care, services, and supports can indeed influence the development of pressure ulcers.47–50 In persons with chronic SCI and pressure ulcers, it is important to assess the individual’s motivation to stay ulcer-free.49,50 Motivation drives the daily actions or inactions of the individual. Lack of motivation to perform preventative activities may be associated with depression, lack of social support, or poverty. Conflicting motivations, such as wanting to stay fully engaged in either vocational or recreational pursuits, may interfere with maintaining a strict regimen of pressure ulcer prevention. Understanding life context, daily routines, and central daily activities should result in a balance between ones daily occupations and pressure ulcer preventative routines. Therefore, in order to most effectively prevent and treat pressure ulcers in any individual, it is important to not just evaluate the usual risk factors as described throughout in this guideline but also to evaluate the context in which the individual with SCI lives, for, if these other factors are not addressed as well, any intervention is not likely to be successful.

Support surfaces for bed and wheelchair: Support surfaces that are old, worn-out, or inappropriate may put the person at risk for pressure ulcers.

The use of both a validated risk assessment tool and clinical judgment to assess risk is strongly recommended. The Salzberg Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Form for SCI is only one risk assessment form validated for persons with SCI.18 However, in many facilities, the Braden scale, which is not specific to SCI, is used to determine persons at risk for PrUs.

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Innovative educational programs are needed to provide persons with SCI with information and the motivation necessary to regain control over their lives. It is necessary to determine how effective these programs are through testing knowledge and observing preventive behavior.

Risk-Based Prevention

A person with an SCI is at risk for the development of pressure ulcers from the moment of injury. Prolonged immobilization during the hours and days immediately after injury significantly increases the risk. Pressure reduction strategies to protect vulnerable areas of the body should be implemented soon after emergency medical intervention and spinal stabilization.

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Pressure ulcer development is a lifelong concern for the individual with SCI.

Prevention strategies must be implemented across the full spectrum of care. A comprehensive preventive plan should be developed for each patient and include information and instructions that are given to patients and their families.51 (See Patient Teaching: Preventing Pressure Ulcers in SCI Patients at Home.)

Printed materials or visual media, such as DVDs, are used frequently to augment educational sessions. Some of these materials may be sent home with patients when they are discharged. Because most patient education programs are hospital based, little is known about what information the patient retains, which behaviors or activities are practiced routinely, and the compatibility of the patient’s lifestyle with prevention strategies. In the 1970s and 1980s, a number of SCI centers established comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention education programs.52,53 Both inpatient and outpatient programs advocated multidisciplinary, coordinated, structured, and wide-ranging approaches to prevention. Some of these programs still serve as models for practice today.54

Several educational needs have been described recently. These include (rank ordered by the authors of the study)55:

- awareness of the lifelong risk for developing pressure ulcers (including the ability to assess personal risk factors and how risk changes over time)

- ability to take charge of personal skin care regimen and to partner with healthcare providers

- ability to perform prevention strategies consistently that are compatible with level of function and activity and update practices as risk changes

- ability to coordinate social supports.

Effective prevention education and early detection of pressure ulcers are critical.50

The concepts of context and lifestyle as they pertain to pressure ulcer etiology, prevention, and management have been described recently in the literature. Clark et al.49 examined the daily lifestyle influences on the development of pressure ulcers among adults with SCI. In-depth interviews and observation were used to obtain detailed descriptive information pertaining to the development of recurring pressure ulcers as they relate to participants’ overall lifestyle, daily routine, choices, challenges, and prevention strategies. These investigators concluded that prevention is dependent on the uniqueness of an individual’s everyday life.49

In a qualitative study50 of 20 adults with SCI and a history of pressure ulcers, investigators identified eight multifaceted, interconnected lifestyle principles that explain pressure ulcer etiology. They include perpetual danger; change/disruption of routine; diminished prevention behaviors; risk ratio of liabilities (risk factors or behaviors ) to buffers (factors, behaviors, or people that reduce risk); individualization; presence of prevention awareness and motivation; lifestyle trade-off; and access to needed care, services, and supports.50

Patient TeachingPreventing Pressure Ulcers in SCI Patients at Home

Patient TeachingPreventing Pressure Ulcers in SCI Patients at Home

Persons with SCI are at risk for developing pressure ulcers, especially after they leave your care. Teach patients and their families the following strategies to help them prevent pressure ulcers after they have returned home:

- Perform daily comprehensive visual and tactile skin inspection.

- Maintain good personal hygiene.

- Turn and reposition often, and perform frequent weight shifts.

- Use appropriate and well-maintained support surfaces for the bed and wheelchair.

- Maintain adequate nutrition.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle (avoid alcohol, tobacco, and illegal drugs).

Skin Assessment

The SCI patient with a pressure ulcer should undergo two assessment phases. The first phase is a comprehensive evaluation and examination, including:

- complete social history including family, financial stability, or other support

- medical history including comorbidities

- physical examination including functional independence (ADLs, mobility, transfer skills)

- laboratory tests and nutrition

- assessment of psychological health, behavior, and cognitive status

- information on social and financial resources and the availability and utilization of personal care assistance

- assessment of positioning, posture, and related equipment

- assessment of lifestyle, including use of tobacco, past and present, and alcohol and drug use/abuse.6

The second phase of assessment consists of a detailed description of the pressure ulcer itself and the surrounding tissues, including the following factors:

- Etiology of the pressure ulcer

- Anatomical location and general appearance and characteristics of the wound base

- Size (length, width, depth, and wound area)

- Stage or severity

- Exudate

- Odor

- Necrosis

- Undermining

- Sinus tracts

- Infection

- Viable tissue (granulation, epithelialization, muscle or subcutaneous tissue)

- Nonviable tissue (eschar, clean nongranulating slough)

- Wound margins and surrounding tissue6

Photographs can be useful in these assessments and in monitoring.

The pressure ulcer should be monitored with each dressing change and the above factors reviewed at regular intervals.

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Patients with darkly pigmented skin are particularly vulnerable to undetected pressure ulcers. Although areas of damaged skin appear darker than the surrounding skin, tactile information must be used in addition to visual data when assessing persons with darker skin. The skin may be taut and shiny, indurated, and warm to the touch. Color changes may range from purple to blue. Remember, pressure-damaged dark skin doesn’t blanch when compressed.56

Treatment

Prevention and treatment are inextricably linked across the continuum of care for the person with a pressure ulcer.57 During rehabilitation following an SCI, the patient is exposed to a great deal of information about the major physiological changes that have occurred as well as how to prevent or manage potential secondary complications, such as pressure ulcers and UTIs. Unfortunately, much of this information isn’t absorbed during this early posttraumatic phase, resulting in episodes of potentially life-threatening conditions once the patient returns to his or her home and community. Coupled with nonretention of information is today’s significant decrease in length of stay, which makes structured education sessions during hospitalization very limited at best or totally absent.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The treatment of pressure ulcers is a complex process, based on a number of patient-related and pressure ulcer–related factors. Nonsurgical treatment for pressure ulcers consists of a number of sequential steps that become the treatment plan for that patient with his or her specific ulcer. The elements of a comprehensive treatment plan include cleansing, debriding, applying dressings, and assessing the need for (and appropriateness of) new technologies aimed at wound healing. Education, in the form of printed materials or discussions with healthcare professionals, is intended to prevent recurrence in the patient with an SCI. Enhanced, individualized pressure ulcer prevention and management education is effective in improving pressure ulcer knowledge during hospitalization for either medical management or the surgical repair of a pressure ulcer.58,59 Furthermore, initial individualized preventive intervention combined with structured follow-up within a person’s individual everyday life setting may reduce the risk of pressure ulcers in persons with SCI.60

Initially, creating a physiologic wound environment is essential. Cleansing is accomplished with normal saline, sterile water, pH balanced wound cleanser, or lukewarm potable tap water. Other cleansing agents (such as diluted sodium hypochlorite ¼ to ½ strength for wounds with heavy bioburden for a limited time) and mechanical wound cleansing techniques are also employed depending on the status of the wound and surrounding tissue. Cleansing is followed by debridement of devitalized tissue and selection of wound care dressing. A number of adjunctive therapies have been identified. However, electrical stimulation is one of the very few to be supported by the scientific evidence. The treatment plan should be modified if the ulcer shows no evidence of healing within 2 to 4 weeks.

Surgical Treatment

Stage III and IV pressure ulcers are frequently treated surgically in patients with SCI. The goals of surgical closure include6,61,62:

- preventing protein loss through the wound

- reducing the risk of progressive osteomyelitis and sepsis

- preventing renal failure

- reducing costly and lengthy hospitalization

- improving hygiene and appearance

- expediting time to healing.

The surgical process includes61,62:

- excision of the ulcer and surrounding scar, underlying bursa, soft tissue calcification, and underlying necrotic or infected bone

- filling dead space with fascia or muscle flaps

- improving vascularity and distribution of pressure over bony prominences

- resurfacing the area with a large flap so that the suture line is away from areas of direct pressure

- providing a flap that leaves options for future surgeries.

Preoperatively, the rehabilitation and surgical teams coordinate their efforts to control local wound infection, improve and maintain nutrition, regulate the bowels, control spasms and contractures, and address comorbid conditions. Previous pressure ulcer surgery, smoking, UTI, and heterotopic ossification could affect surgical outcomes.6

New surgical techniques to repair pressure ulcers have been developed and are being used to improve surgical outcomes. Although these techniques are being evaluated,63–67 reports of long-term follow-up of the status of the skin and recurrence have been limited. One study by Lee63 used a new wound closure technique and followed patients for 102 days, after which 18 of 21 (86%) wounds in 13 patients remained closed. Sorensen et al.68 suggested that thorough preoperative debridement, patient compliance, control of comorbidities, professional postoperative support, and sufficient pressure relief are essential if surgical success is to be achieved.

Evidence-Based PracticeEvidence-Based Practice

Evidence-Based PracticeEvidence-Based Practice

Postsurgical care includes keeping the surgical site pressure-free, preventing infection, preventing dehiscence of a flap, using specialty beds to maximize pressure reduction, mobilizing the patient progressively, and providing patient and family education.6

Support Surfaces

Support surfaces are devices or systems intended to reduce the interface pressure between a patient and his or her bed or wheelchair.57 Support surfaces neither prevent nor heal pressure ulcers; rather, they are prescribed by a clinician and incorporated into a comprehensive pressure ulcer prevention and management program. Pressure redistribution products, such as active or reactive mattresses, mattress overlays, or specialty beds, may be used at various times to reduce the patient’s risk of developing pressure ulcers. Reactive support surfaces are used for individuals who have a stable spine and who are able to reposition themselves enough to avoid weight bearing on all areas at risk for pressure ulcers. Active support surfaces and a high air-loss or air-fluidized reactive support surface are for individuals who have pressure ulcers on multiple turning surfaces and/or status postflap/skin graft within the past 60 days.6 Bed positioning devices and techniques must be compatible with the bed type and the individual’s health status. Individuals should not be positioned directly on a pressure ulcer. Rather various positioning aids, such as pillows, and cushions should be used to reduce pressure on areas vulnerable to tissue breakdown. Although there is controversy regarding the frequency of turning or repositioning a person with a pressure ulcer, the literature supports the importance of individualizing a turning schedule. There are a great number of pressure redistribution bed support surfaces for individuals with or at risk to pressure ulcers. The use of these “specialty beds” is determined by the person’s status and the individual facility’s experience with these devices. These include air-fluidized and low-air devices.

Materials for wheelchair positioning and pressure ulcer prevention, such as foams and gels, used alone or in combination, and elements such as air and water, also used alone or in combination, are being used across inpatient and home environments. Wheelchairs and seating systems should be specific to the individual and allow that individual to redistribute pressure sufficiently to prevent pressure ulcers. The optimum wheelchair seating system should6:

- redistribute pressure

- minimize shear

- provide comfort and stability

- reduce heat and moisture

- enhance functional activity

- be inspected at regular intervals for wear.

Wheelchair cushions and seating systems of various materials and designs are intended to reduce pressure and maximize balance and stability when a patient is in a wheelchair. It must be stated emphatically that wheelchair cushions neither prevent nor heal pressure ulcers. Rather, they are used as one important tool in the clinician’s armamentarium of prevention and treatment strategies. Power weight-shifting wheelchairs are often prescribed for individuals who are unable to independently perform an effective pressure relief while sitting. Full-time wheelchair users with or without a history of pressure ulcers should limit sitting and maintain an off-loaded position from the seating surface for at least 1 to 2 minutes every 30 minutes.6 (For further discussion on support surfaces, see Chapter 11, Pressure Redistribution: Seating, Positioning, and Support Surfaces.)

Adverse effects of pressure on tissue are a major source of morbidity and mortality in persons with SCI.6 Issues surrounding wheelchair sitting and associated seating and positioning devices have been studied extensively and therapeutic strategies developed to minimize pressure on the skin, especially in anatomical areas overlying bony prominences.69–71 These efforts have led to major improvements in the technology of seating support and pressure-reducing devices such as wheelchair cushions and in mattresses for the supine patient.

Another area remains as yet uninvestigated, namely, the adverse effects of pressure exerted while sitting on a commode chair during bowel care procedures necessary for persons with SCI. Chronic constipation, difficulty in evacuation, incontinence, and damage to mucosa are all complications associated with neurogenic bowel in persons with SCI. One attempt to deal with the adverse effects of pressure during bowel management programs is the padded commode seat. This has led to some success in safety and in reducing the risk of pressure ulcers during the bowel management procedures.72–76 Rates of rehospitalization following SCI remain high and result from complications in the genitourinary system, respiratory complications, and pressure ulcers.15 Unfortunately, very little data exist on the specific nature of pressure ulcer development in association with bowel care sitting time or process. Research is needed on an equally relevant therapeutic approach that would focus on duration of sitting time during each evacuation attempt.

New Interventions

A number of adjunctive therapies have been reported in the literature with varying degrees of success in treating pressure ulcers in the patient with an SCI, including:

- electrical stimulation

- ultraviolet and laser therapy

- hyperbaric oxygen and ultrasound

- negative pressure wound therapy

- nonantibiotic drugs

- topical agents

- skin equivalents

- growth factors.

Among these, only electrical stimulation has enough reported scientific evidence supporting it to justify its use as a treatment for pressure ulcers in the patient with an SCI.77,78

Summary

Although SCI research has increased tremendously in recent years, designing and conducting randomized, controlled trials that are capable of producing compelling observational evidence on which to base management of pressure ulcers have been disappointing. Despite advances in pressure ulcer treatment, little scientific evidence points the way to preventing pressure ulcers in the SCI population. Randomized, controlled trials in real-world settings are the gold standard for assessing the effectiveness of prevention and treatment strategies. However, in complex, rapidly changing healthcare settings, blinding is infeasible and it may be impractical to control for every variable that influences a study’s outcome. Furthermore, any assumptions that usual care is static are probably mistaken. Innovative approaches to maintain the integrity of the study design must be used, including flexibility in inclusion and exclusion criteria to support accrual, obtaining a better understanding of the important aspects of usual care that may need to be standardized, continuous improvement within the intervention arm, and anticipation and minimization of risks from organizational changes.31 Research efforts should focus on prospective studies to prevent recurrence that include long-term follow-up programs promoting self-management.

PATIENT SCENARIO: SPINAL CORD INJURY POPULATION

PATIENT SCENARIO: SPINAL CORD INJURY POPULATION

Clinical Data

Mr. K is a 48-year-old African American man who sustained a complete SCI at the T8 level from a motor vehicle crash 7 years ago that resulted in paraplegia. He lives independently, is unmarried and unemployed, and has a history of hypertension. During his rehabilitation hospitalization, Mr. K was told about pressure ulcers and what he could do to prevent them. However, within 1 year after discharge, he developed a stage III right ischial pressure ulcer for which he was hospitalized for surgical repair. The surgery resulted in a healed ulcer, and Mr. K. was discharged. Although pressure ulcer prevention was reviewed during this hospitalization and consumer-based written material was provided, he returned home and resumed previous habits, including sitting in front of the television for long hours, driving around with friends, not eating well, and smoking. Less than a year after the first surgery, Mr. K developed a stage IV pressure ulcer with osteomyelitis on his left ischium. He was readmitted to the hospital for the surgical repair of this ulcer. Compounding Mr. K’s pressure ulcer history are the following: He does not have a support system to help and encourage him to be more proactive in preventing pressure ulcers; he seems depressed and unable to take control of his physical health; he would like to return to work as a computer programmer but has not put much effort into looking for a job; he often does not take his prescribed medication for hypertension; he developed type 2 diabetes; and he smokes and sometimes uses alcohol and illegal drugs. His bowel care required several hours on the commode, contributing to pressure ulcer recurrence on fragile skin.

Case Discussion

The first priority is to treat the infection (osteomyelitis) and surgically repair the ulcer. During this hospitalization, a case manager was assigned to coordinate discharge and follow-up plans. The case manager requested that an occupational therapist knowledgeable about SCIs and pressure ulcers work with Mr. K to develop strategies to prevent future pressure ulcers, help him to take control of the things he can control, identify appropriate support systems within the community and the healthcare system, and improve his quality of life. The occupational therapist worked with Mr. K to develop a pressure ulcer prevention plan that was acceptable and appropriate to Mr. K’s lifestyle. Relevant actions and behaviors were included in a written plan so Mr. K could refer to it daily. These included weight shifts and turns, skin checks (with special attention to the changes in his darkly pigmented skin), nutrition, hygiene, limiting sitting in one place for long periods of time, consistency with prescription medications, limiting smoking and drinking, and not using drugs. Additionally, the occupational therapist performed a complete assessment of Mr. K’s support surfaces used in the bed and wheelchair as well as the wheelchair itself. His wheelchair and wheelchair cushion were in very poor condition. A new wheelchair was ordered and a pressure evaluation performed to identify the most effective wheelchair cushion for him. A mattress overlay, compatible with his bed at home, was also prescribed.

Mr. K was instructed on the routine care of his new equipment (wheelchair, mattress overlay, and cushion), especially with regard to changes in his skin that might reflect the deterioration of the support surfaces. He was re-evaluated for management of his hypertension, and a new medication regimen was designed. A program to manage his diabetes also was implemented. His bowel regimen was reviewed and modified, and a new commode/shower chair was ordered. A home visit by the occupational therapist identified ways to minimally adapt Mr. K’s home environment to maximize his independence and safety. He was referred to a psychologist for counseling that seemed to result in better insight into his behaviors and lifestyle. Finally, Mr. K was given a list of resources he could contact with problems, including the case manager, equipment vendor, physician, and clinics. He also was given information on how to seek employment.

HIV/AIDS POPULATION

Carl A. Kirton, DNP, RN, ANP-BC, ACRN

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- describe the impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) on the prevalence of skin disorders in the patient with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

- describe six common infectious skin disorders and two common noninfectious skin disorders in the patient with HIV or AIDS that results in altered skin integrity

- discuss two of the neoplastic skin disorders seen in the patient with HIV or AIDS.

Skin Alteration in HIV and AIDS Patients

More than 90% of HIV-infected patients will develop at least one type of dermatologic disorder during the course of their HIV infection.1 In fact, in the early 1980s, it was the identification of an unusual skin lesion in young homosexual men that prompted the search for the virus that causes AIDS. A broad range of infectious and noninfectious skin lesions may develop during both the asymptomatic and symptomatic courses of the disease. Alteration in the skin is often the first manifestation of an impaired immune system and may be a sign or symptom of a serious opportunistic infection. Skin alterations can also indicate advancing HIV disease.

Several points regarding HIV, skin disease, and its treatments are noteworthy. Lesions that are common in the non–HIV-infected adult population may present atypically in HIV-infected persons. In addition, skin disorders often aren’t responsive to the usual treatments, may be present for longer than expected, and may develop into chronic, disfiguring disorders. Skin lesions may also be the precursor of a life-threatening illness.

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Prompt and accurate investigation of skin lesions in the HIV-infected patient is essential and often warrants collaboration with an HIV specialist.

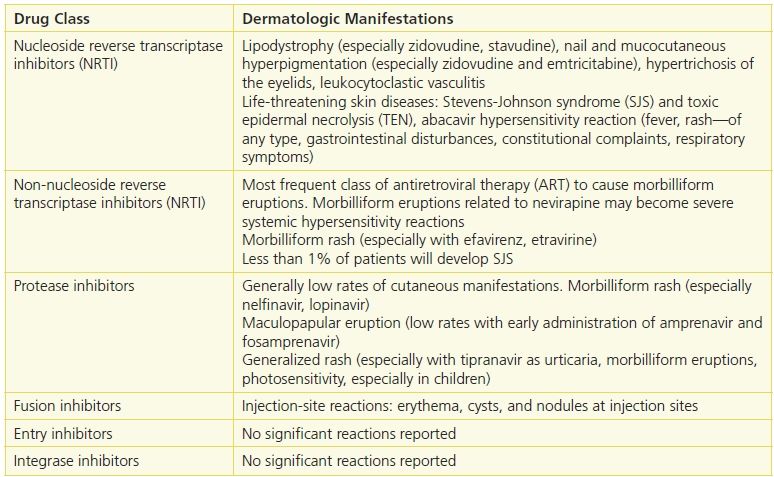

The effective combination of several antiretroviral drugs to suppress viral replication with consequent repletion of the CD4+ lymphocyte count is the standard of care treatment for HIV infection. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) and drugs that prevent or treat opportunistic infections have contributed to a significant decline in HIV-associated morbidity and mortality. The introduction of ART has also resulted in a dramatic decline in HIV immunosuppression–related diseases including skin diseases, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, eosinophilic folliculitis, molluscum contagiosum, bacillary angiomatosis, and condylomata acuminata. One study estimated that after the introduction of protease inhibitors (often called the post-HAART era), the total number of HIV patients with skin problems was reduced by 50%.2,3 Although ART and regimens to treat opportunistic infections have improved the quality of life for patients by controlling HIV replication, the increased use of pharmaceutical agents has led to an increased incidence of adverse reactions to these drugs.4–6 The risk for adverse cutaneous reactions to certain drugs is greatly increased in patients with HIV compared with that of the general population (as much as 100 times) and occurs in tandem with the level of immunosuppression.7 Drugs often associated with adverse effects include sulfonamides, co-trimoxazole, and tuberculostatics as well as many of the antiretrovirals. (See Table 21-2.)

Table 21-2 Adverse Cutaneous Reactions in HIV Disease

Cutaneous Drug Eruptions

Cutaneous drug-induced eruptions, not due to ART, can occur with some drugs used to prevent opportunistic infections. Bactrim (trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole), the most effective drug in the prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia, is known to cause cutaneous eruption in patients with HIV infection. The rate of cutaneous eruption associated with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole in HIV patients is 20% to 80% compared with 1% to 3% in persons without HIV infection, possibly due to altered drug metabolism, decreased glutathione levels, or both.8

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Approximately 50% to 60% of HIV-positive patients have been shown to develop a morbilliform eruption within 7 days of starting trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole therapy. A trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole drug eruption is characterized by the widely disseminated spread of fine pink to red macules and papules involving the trunk and extremities. The clinician must provide a complete head-to-toe examination of the skin within the first week of therapy and teach the patient to notify the provider of any unusual skin eruptions.

In its severe form, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) may also develop. SJS is characterized by fever as well as widespread blisters of the skin and mucous membranes of the eye, mouth, or genitalia. TEN is a more serious manifestation of SJS that involves widespread areas of the skin with confluent bullae that can lead to loss of skin in massive sheets.

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

TEN may lead to secondary infection with sepsis, volume depletion, and high-output cardiac failure as a consequence of widespread denudation of the skin. Patients who develop TEN must be treated aggressively in an acute care setting.

Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) (also referred to as “immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome” or “immune restoration disease”) is a syndrome characterized by a paradoxical clinical deterioration in or an exacerbation of certain conditions, some of which may potentially manifest in the skin and may occur in as much as 40% of commencing ART.9 IRIS is thought to be the result of an overzealous immunologic response to infectious or self-antigens as the immune system is restored with HAART. IRIS results in frank disease but often results in moderate to severe cutaneous eruptions, including follicular inflammatory eruptions, mycobacterial skin infections, and viral infections such as human herpes virus infection (e.g., herpes zoster). IRIS may even exacerbate an underlying autoimmune disease such as lupus erythematosus.

Infectious Skin Disorders

The immunocompromised status of patients with HIV or AIDS puts them at greater risk for infectious bacterial or viral skin disorders, such as herpes virus, cytomegalovirus (CMV), human papillomavirus, molluscum contagiosum, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus infection, and bacillary angiomatosis.

Herpes Virus

Breakouts of grouped blister-like lesions typically caused by the common herpes virus are easily recognized and common in patients with HIV at all stages of the disease. Herpes zoster may occur either early or late in the course of HIV-induced immunosuppression and may be the first clinical clue to suggest undiagnosed HIV infection. Herpes infection may occur on the oral and genital mucosa as well as in the perianal region. Lesions typically manifest as painful, grouped vesicles on an erythematous base that rupture and become crusted. History and clinical presentation are often all that’s necessary to establish the disorder; therefore, confirmatory tests, such as viral cultures, HSV DNA, and HSV antigen detection assays, are rarely necessary. In patients with advanced HIV, a herpetic infection may develop into chronic ulcers and fissures with a substantial degree of edema.

Infections with human herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and type 2 (HSV-2) are common, with a seroprevalence of HSV-1 among adults in the United States of approximately 60% and a seroprevalence of HSV-2 among persons aged ≥12 years of 17%. Approximately 70% of HIV-infected persons are HSV-2 seropositive and 95% are seropositive for either HSV-1 or HSV-2.10 Herpes zoster can occur in HIV-infected adults at any CD4+ count, but the frequency of disease is highest in those with CD4+ counts less than 200 cells/μL. Unlike other skin disorders, the incidence of herpes zoster infection is not reduced by ART.

Patient TeachingHerpes Virus Teaching Tips

Patient TeachingHerpes Virus Teaching Tips

- Scrupulous hand washing helps prevent the spread of infection.

- Use individual washcloths and linens.

- Mild analgesics may be necessary for pain associated with herpes infection.

- Topical soaks (such as Domeboro solution) can be used to help dry wet lesions.

- Impetiginization of skin lesions may be treated with warm compresses.

Uncomplicated zoster outbreaks should be treated for 5 to 10 days with acyclovir (Zovirax), famciclovir (Famvir), or valacyclovir (Valtrex). Painful atrophic scars, persistent ulcerations, and acyclovir-resistant chronic verrucous lesions may also develop. (See Patient Teaching: Herpes Virus Teaching Tips.)

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Healing of herpetic lesions is usually complete in less than 2 weeks. If they haven’t healed within 3 to 4 weeks, the patient may have a drug-resistant virus. Acyclovir-resistant cases of varicella-zoster virus or herpes simplex virus infection require treatment with IV foscarnet (Foscavir).

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

A patient with herpes zoster involving V1, the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve, should be referred to an ophthalmologist immediately due to the risk of corneal ulceration. Signs or symptoms of this condition, such as painful vesicular lesions on the tip of the nose or lid margins, should be considered an ocular emergency.

Cytomegalovirus

CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus in the herpes virus family that can cause disseminated or localized end-organ disease among patients with advanced immunosuppression. The incidence of new cases of CMV end-organ disease has declined by 75% to 80% with the advent of ART.10 When the skin is involved, CMV may cause a number of different clinical manifestations, including ulcers, verrucous lesions, and palpable purpuric papules. Effective treatments for a CMV infection include oral valganciclovir (Valcyte) or IV ganciclovir (Cytovene), foscarnet (Foscavir), or cidofovir (Vistide).

Practice PointPractice Point

Practice PointPractice Point

Ulcers are commonly secondarily colonized with CMV, and many patients have combined herpes simplex and CMV infections.

Human Papillomavirus

The most common skin complaint of HIV-positive patients is warts caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). It has been shown that immune deficiency is associated with increased frequency of HPV infections, suggesting that the emergence of HPV is modulated by the patient’s immune status.

Verruca vulgaris warts (common warts) appear as dull-colored papules that can erupt anywhere on the skin; verruca plana warts are flat-topped, skin-colored papules on the face and dorsal hands. Condyloma acuminata warts (genital warts) are characterized by soft, skin-colored cauliflower papules on the genital areas. Their appearance, size, and number vary with the site. Warts can range in size from less than 1-mm to 2-cm “cauliflower lesions.” Verruca plantaris warts are hyperkeratotic papules and plaques that appear on the soles of the feet. Certain types of HPV have oncogenic potential and are associated with cervical cancer in women, bowenoid papulosis of the penis, anal cancers, and invasive carcinoma. HPV-16 alone accounts for approximately 50% of cervical cancers in the general population and HPV-18 for another 10% to 15%, whereas the other oncogenic HPV types each individually account for less than 5% of tumors.10 Unlike other HIV-associated infections, treatment with ART has not affected the incidence of HPV infection.

Treatment, although effective, rarely eradicates HPV entirely. Destructive measures—such as the application of topical chemicals (e.g., salicylic or trichloroacetic acid), cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, and ablative surgery—are standard measures used for common verrucae (warts). Condyloma acuminata can be treated by using podophyllin resin 10% to 50% in tincture of benzoin, 3% cidofovir ointment, intralesional interferon-a, liquid nitrogen cryotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage, or carbon dioxide laser.

Patient TeachingPatient Teaching

Patient TeachingPatient Teaching

Imiquimod cream 5% or podofilox 0.5% or sinecatechin 15% is often prescribed for home application to prevent recurrence of HPV infection. Instruct the patient to apply the medication to his or her warts at night three times per week for up to 16 weeks.

Patients who use these creams may experience application-site reactions such as itching and/or burning. Skin reactions may be of such intensity that patients may require rest periods from treatment. Teach the patient to use the cream exactly as prescribed; using too much cream, or using it too often or for too long, can increase chances of having a severe skin reaction.

Patient TeachingPostprocedure Care after HPV Surgical Excision

Patient TeachingPostprocedure Care after HPV Surgical Excision

Postprocedure patient teaching should include the following:

- Medication usually isn’t needed after removal of lesions. Topical anesthetic ointments may be used to minimize discomfort. Sitz baths may aid resolution when large areas are treated; silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) ointment or antibiotic ointment may not only be soothing but may also reduce the possibility of superficial infection. No dressing is required, but some patients may request a sanitary napkin for treated genital lesions. Ice packs are helpful.

- Cryonecrosed lesions will progress from erythema to edema and then will turn black. The lesions will disappear within a few days, and healing should be complete in 7 to 8 days. For chemically cauterized lesions, the healing process is usually less than 1 week.

- Treated areas should be washed and dried gently each day of the healing process. Postcryotherapy management is similar to that for a superficial partial-thickness burn.

- If acute discomfort persists beyond 48 hours, instruct the patient to contact the physician.

- Rarely, a mixture of equal parts of 20% benzocaine (Hurricaine) ointment and topical antibiotics may be used. Lidocaine ointment 5% provides excellent relief and also keeps the tissues moist.

- Counsel the patient to report excessive discomfort or any signs of infection.11

Plantar verrucae are generally treated with topical 40% salicylic acid plaster applied daily, with paring of hyperkeratotic areas, although intralesional bleomycin and liquid nitrogen therapy have also been used. Verruca plana warts are commonly treated with topical tretinoin alone or in combination with 5-fluorouracil. Light electrodessication or liquid nitrogen application may be used as an adjunct therapy. Verrucous carcinoma requires excisional surgery. (See Patient Teaching: Postprocedure Care after HPV Surgical Excision.)

Molluscum Contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is a benign, usually asymptomatic viral skin infection caused by the poxvirus; it is spread by direct contact and causes no systemic manifestations. The diagnosis can usually be made from the characteristic appearance of dome-shaped, umbilicated, translucent papules that may develop on any cutaneous site, especially the genital areas and the face. In the patient with AIDS, lesions may become widespread, disfiguring, and resistant to treatment. The lesions appear verrucous, pruritic, or eczematous. Once they become confluent, they can be difficult to treat. Although the exact incidence of molluscum contagiosum in patient with AIDS is unknown, it is estimated to be 5% to 18%.12 Treatment is generally by destructive measures, including cryotherapy or curettage. (See Patient Teaching: Molluscum Contagiosum.)

Patient TeachingPatient Teaching

Patient TeachingPatient Teaching

Molluscum Contagiosum

- Molluscum contagiosum can be transmitted through direct contact.

- The lesions are prone to autoinoculation, and in male patients, shaving the beard area has been reported to cause particularly severe infections, with lesions encompassing the entire face.

- Covering lesions with clothing and/or bandages is one effective way to prevent spread.

- Good hand hygiene and avoiding touching the lesions is another way to prevent spread of fomites.

- Cryonecrosed lesions will progress from erythema to edema and then will turn black. The lesions will disappear within a few days, and healing should be complete in 7 to 8 days.

- For chemically cauterized lesions, the healing process is usually less than 1 week.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree