R. Gary Sibbald, BSc, MD, MEd, FRCPC (Med)(Derm), MACP, FAAD, MAPWCA

Sharon Baranoski, MSN, RN, CWCN, APN-CCNS, MAPWCA, FAAN

The contribution of Janet E. Cuddigan PhD, RN, CWCN, in previous additions is gratefully acknowledged.

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- assess the purpose of debriding a wound

- evaluate criteria for not debriding a necrotic wound

- describe types of debridement, including sharp/surgical, conservative surgical, mechanical, maggot, enzymatic, and autolytic

- compare the advantages and disadvantages of each type of debridement

- select the most appropriate method of debridement depending on patient preference, clinician expertise, and healthcare system resources.

Speeding the Healing Process

Debridement is an important component of the wound bed preparation (WBP) management model.1–4 After considering the cause of the wound and patient-centered concerns, debridement is a necessary step in local wound care.1,2,4 Debridement is the removal of necrotic tissue, exudate, bacteria, and metabolic waste from a wound in order to improve or facilitate the healing process.3,4 Accumulation of necrotic tissue usually results from poor blood supply, a prolonged inflammatory process, bacterial damage, or an untreated cause of the wound (e.g., uncontrolled edema leading to increased interstitial pressure or other mechanical, chemical, or traumatic injury). In otherwise healthy people, natural debridement often keeps pace with the accumulation of dying tissue in a wound. If the host resistance is impaired by poor nutrition, continued pressure damage, or other comorbidities such as uncontrolled high blood sugar in a person with diabetes, medical intervention is required to facilitate wound healing.

The primary purpose of debridement is to reduce or remove dead and necrotic tissue in a healable wound because this tissue is a proinflammatory stimulus and a culture medium for bacterial growth.1,3,4 The removal of dead and necrotic tissue is necessary to reduce the biological burden of the wound in order to control critical colonization on the wound surface and prevent deep and surrounding wound infection, especially in deteriorating wounds.4 Debridement allows the practitioner to visualize the sides and base of a wound more accurately to determine whether viable tissue is present. (Keep in mind that a pressure ulcer that is covered with necrotic tissue cannot be numerically staged until debridement is completed.). Necrotic tissue that is not removed not only impedes wound healing but also can result in spread of bacterial damage to deeper tissue, causing surrounding cellulitis, osteomyelitis, and the possibility of septicemia, preventable limb amputation, or death. By removing necrotic tissue, debridement creates an acute wound within a chronic wound, restoring nutrient supply from the underlying circulation and facilitating optimal available oxygen delivery to the wound site.4,5

For a wound to heal, it must have a microenvironment free from the nonviable tissue that serves as a bacterial culture medium to increase bacterial metabolism and proliferation.6 Oxygen is a primary requirement for this energy-dependent metabolic process to occur. The production of free radicals crucial to wound healing facilitates this process by killing bacteria and promoting the proliferation of both fibroblasts and epithelial cells. However, bacteria that are present in hypoxic conditions (anaerobes, facultative aerobes, and bacteria in biofilms) compete with healing tissue for nutrients and produce exotoxins and endotoxins that damage newly generated, mature cells. This setting of hypoxia and bacteria interrupts the fundamental wound healing process of fibroblast migration into the extracellular matrix. Fibroblasts excrete procollagen fibers that are assembled in the extracellular space with the aid of vitamin C into a collagen matrix that forms the building blocks of granulation tissue. This process allows a chronic wound stuck in the destructive abnormally prolonged inflammatory stage to move to the proliferative stage, promoting new tissue formation and laying the foundation for healing with the necessary recruitment of fibroblasts to deposit collagen.6

Leukocytes—primarily polymorphonuclear cells—are the primary cells of the acute inflammatory process of wound healing. They enter the wound and aid in the removal of devitalized tissue and foreign material. Collaboration of local enzymes (metalloproteases, elastases, or collagenases) also helps to dissolve and remove devitalized tissue. Because collagen comprises approximately 75% of the skin’s dry weight, the overall endogenous collagenase is considered to be one of the main regulators of tissue remodeling in the process of wound healing. Remodeling is part of the healing process in which the wound restructures into its final functional image.

Tissue injury is followed by a clotting stage and then the inflammatory stage to remove tissue debris. After wound debris is removed, macrophages are recruited; they, in turn, recruit fibroblasts, which deposit collagen and fill the wound space with scar tissue. An acute wound of reasonable size with adequate blood supply for healing and essential nutrients generally results in a “healed” closed wound within 14 days—but this doesn’t represent the total healing process. Remodeling, or maturation, typically takes another 4 weeks, making the total healing process about 6 weeks, but the further increase in tensile strength can take a year or even longer. Other factors may be involved in the healing process as well. For example, a wound that appears in an area of rich blood supply (e.g., scalp) will heal faster than a wound in an area with a lesser blood supply (e.g., sacrum). Abnormal collagen breakdown and new collagen buildup occur in a balanced growth pattern resulting in a normal-appearing scar. However, excess collagen can form a hypertrophic scar or keloid. A hypertrophic scar represents disordered collagen within the scar tissue margins of a healed wound. A keloid extends beyond the wound scar margin with a greater disorganization of collagen fibers. (Chapter 9, Table 9-8 and Figure 9-29.)

Identifying Necrotic Tissue

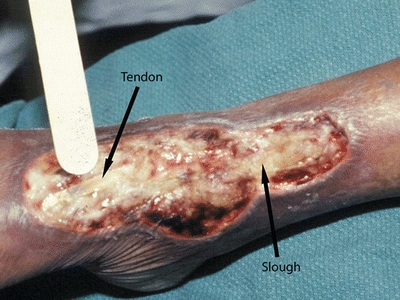

Dead or necrotic tissue may be loose and moist or dry and firm. This tissue is identified by its soft loose moist, yellow, green, or gray appearance and may become hard thick and leathery with a dry black eschar (Fig. 8-1). Oxygen and nutrients can’t penetrate the portion of a wound composed of necrotic tissue. Dead tissue is the breeding ground for bacteria, and the eschar may mask an underlying abscess.7 Necrotic tissue that is soft, moist, stringy, and yellow is referred to as slough (devitalized/avascular) tissue.8–11 While some clinical experts have questioned whether slough is in fact tissue or an inflammatory by-product,10 the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP)/European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance (PPPIA) 2014 clinical practice guideline did define slough as “soft, moist, devitalized (non-viable) tissue. It may be white, yellow, tan, or green and it may be loose or firmly adherent” (p. 287)11 (Fig. 8-2). Regardless of whether slough is or is not tissue, clinicians agree that it must be removed in acute and chronic wounds where the goal of care is healing.4,8,9,11–13

Figure 8-1. Eschar. In a wound that has become dehydrated, necrotic tissue turns thick, leathery, and black. This tissue is referred to as eschar.

Figure 8-2. Slough. Necrotic tissue that’s moist, stringy, and yellow (devitalized tissue) is referred to as slough.

In general, removing necrotic tissue restores the local vascular supply to the wound and improves healing. However, debriding too much viable tissue can destroy the collagen structural framework for healing. Some wounds shouldn’t be debrided at all. Exercise caution, for example, in dealing with necrotic ulcers in persons with compromised vascular supply or immunocompromised.11 Debriding heel ulcers remains controversial because of problems with perfusion and the small amount of tissue that covers the calcaneus bone.8,11 There is consensus that a vascular assessment needs to be performed to ascertain if there is an adequate vascular supply to heal prior to debridement of ulcers in the lower extremities.1,8,11 Controversy revolves around whether to debride stable, adherent eschar with no exudate or signs of infection.1,8,11 Some clinicians believe that although caution is indicated, all necrotic heels should be debrided.9,12 The 2014 NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA pressure ulcer guideline state that stable, hard dry eschar should be assessed for signs of infection (erythema, tenderness, edema, purulence, fluctuance, crepitus, and/or malodor) and then debridement in the presence of adequate blood supply.11 Wounds become larger with debridement, something that should be discussed with the patient/family.

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a neutrophilic disorder that has a raised translucent border that rapidly expands the central ulcer. This condition may be idiopathic or associated with underlying inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, or myeloproliferative disease (leukemia/lymphomas). When the raised peripheral border is active, pyoderma gangrenosum is one example of a wound that should not be debrided2. A raised active border indicates an acute inflammatory reaction, and debridement would stimulate the infiltrate even more through a process called pathergy.2 Septicemia is another condition that requires serious caution before initiating debridement. The wounds of patients with septicemia should not be debrided unless the patient is receiving adequate systemic antibacterial coverage.2

Practice Point

Practice Point

Monitor stable necrotic heels for odor and signs of edema, erythema, tenderness, fluid wave, purulence, crepitus, malodor, or drainage that may signal the need for debridement.11

Practice Point

Practice Point

It’s often important to watch the line of demarcation between viable and necrotic tissue for signs of further tissue breakdown or softening eschar.

Chronic wound care begins with treating the cause and patient-centered concerns, including pain and activities of daily living. Assess individual patients to determine whether the wound is healable, maintenance, or nonhealable. To assess healability, an adequate blood supply needs to be present.1,4,11 Palpable pulses in the foot indicate a pressure in excess of 80 mm Hg and enough blood supply for healing to occur. This finding could equate to an ankle-brachial pressure index of 0.6 or higher. If there is a sufficient blood supply and the cause has been corrected (compression for venous ulcers and pressure offloading for diabetic neurotrophic foot ulcers), the ulcer is healable. For pressure ulcers, the source of tissue damage needs to be corrected, including high blood pressure, poor nutrition, friction and shear, decreased mobility, or excess local moisture. Active debridement can be coupled with moisture and bacterial-balanced dressings.

A maintenance wound is one that has a sufficient blood supply for healing but is unable to heal due to patient or health delivery system factors.4 Debridement and local wound care should then be conservative for maintenance wounds. This often includes the removal of nonviable slough but not an active debridement with removal of healthy tissue to create bleeding tissue (an acute wound in a chronic wound). A nonhealable or palliative wound does not have enough blood supply to heal; therefore, debridement should be conservative and limited to easy to remove soft slough with a local antimicrobial (such as povidone–iodine or chlorhexidine) and moisture reduction to reduce local bacteria.4

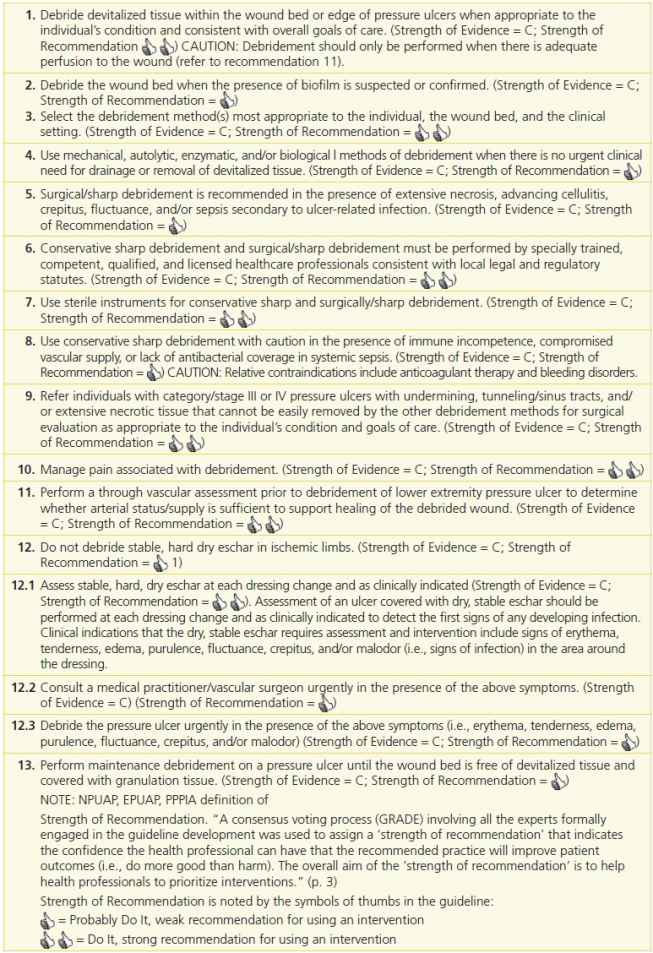

Although it is acknowledged that debridement is a critical first step in preparing the wound bed for healing, all of the recommendations on debridement from the international NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA 2014 clinical practice guideline are at the C level of knowledge11 (Table 8-1).

Table 8-1 Debridement Recommendations: NPUAP/EPUAP/PPPIA 2014 Pressure Ulcer Clinical Practice Guideline

Emily Haesler (ed)., National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline. ; Perth, Australia: Cambridge Media, 2014:154–160.

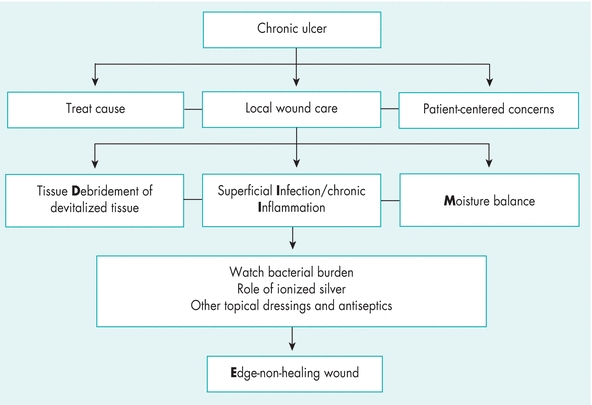

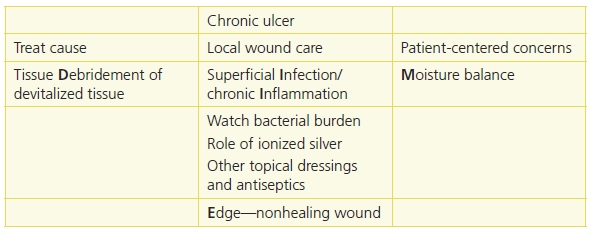

WBP is the management of a wound to accelerate endogenous healing or to facilitate the effectiveness of other therapeutic measures.1,3,4,12 The original TIME model—Tissue nonviable or deficient, Infection or inflammation, Moisture imbalance, Epidermal margin nonadvancing or undermining3—has been reconceptualized to the DIME© model (Fig. 8-3).1,4,12 As mentioned previously, you should first identify and treat the cause of the wound, address patient-centered concerns, and finally provide local wound care (Table 8-2).4,12

Figure 8-3. TIME is now DIME: Wound bed preparation DIME© model. (Reprinted with permission of Wound Care Canada, the official publication of the Canadian Association of Wound Care. Available at: http://www.cawc.net. ©2006.)

Table 8-2 TIME is Now DIME: Wound Bed Preparation DIME Model

Reprinted with permission of Wound Care Canada, the official publication of the Canadian Association of Wound Care. Available at: http://www.cawc.net. © 2006. Keast, D.H., Parslow, N., Houghton, P.E., et al. Best Practice Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Update 2006. Canadian Association of Wound Care. Available at http://www.cawc.net/images/uploads/wcc/4-1-vol4no1-BP-PU.pdf.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Save time and use the DIME1,3,4,12 acronym in preparing the wound bed for healing.

- Debridement

- Infection or inflammation

- Moisture imbalance

- Edge—nonhealing

Predebridement Teaching

Patient-centered care should include teaching about the purpose and usual expectations of the debriding process. Before initiating as a treatment, the process needs to be explained and understood by the patient, their family, and their circle of care. Circle of care is an expression, which includes the individuals and activities related to the care and treatment of the patient. Thus, it covers the healthcare providers who deliver care and services for the primary benefit of the patient. Include in your teaching the debridement options that could be used and the method chosen should be acceptable to the patient and clinician with the desired outcome and potential complications. It is vital that the patient and family understand why the necrotic tissue is being removed. The importance of educating patients and their families and obtaining written consent prior to debridement is one of the ten recommendations for conservative sharp wound debridement published by the Canadian Association for Enterostomal Therapy (CAET).14 Some laypersons mistakenly believe that necrotic tissue is a “scab” (eschar) and is a sign of healing. They need to know that epithelium needs a firm pink surface of granulation tissue base at the wound edge to migrate optimally toward the center of a wound. Delayed healing will result if epithelial margins need to migrate down valleys under eschar or over hypertrophic or unhealthy bright red friable granulation tissue. Similarly, patients and families need to know that the wound will change during the debridement process because an acute wound is created within a chronic wound to stimulate the healing process. For example, tell them to expect the wound to become larger in size.

Another patient-centered concern within the WBP model is pain. (See chapter 12, Pain management and wounds for an extensive discussion on pain). Adequate wound debridement needs to consider how debridement pain will be managed. In an outpatient setting, for example, a wound clinic or practitioner’s office, application of a topical local anesthetic agent prior to debridement may be adequate for small-size wounds. For larger wounds requiring more extensive debridement, surgical debridement may need to take place in the operating room where an anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist can administer regional or general anesthesia. As with any surgery, a preoperative evaluation of the patient is performed by the anesthesiologist or nurse anesthetist to assess individual patient needs15. Wound care patients may have more comorbidities that need to be identified and evaluated prior to debridement. In one medical center, there were higher operative risks identified through higher American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores for wound patients (3.09) compared to other surgical patients (2.09).15 Another safety example is a patient with a cardiac pacemaker or internal defibrillator will need a comprehensive assessment including knowing the specific type and manufacturer of any implanted devices and getting the cardiac device interrogation performed before the patient arrives on the operating table.16 Some pacemakers (mostly older models) may malfunction with electrocautery devices used for hemostasis of bleeders.

If a patient is unable to express their pain experience, a family member may be advocating for them so that they do not experience pain.17 One such patient population includes patients with the locked-in syndrome (LIS). LIS can occur from a basilar artery thrombosis that results in a ventral pontine infarction leaving the patient without motor function. Although the patient cannot move or speak, and even though the patient’s eyes may be closed, the patient may be awake and conscious and thus able to experience pain.17 Special monitoring in the OR using bispectral (BIS) monitoring will facilitate adequate pain management during debridement.17 Patients, their family, and circle of care need to understand that either regional or general anesthesia may be appropriate choices for debridement pain management in the OR.18

Debridement Methods

Mechanical, sharp/surgical, enzymatic, and autolytic are the common methods of debridement.1,2,4,8,11 However, a resurgence in the use of older methods, such as maggots (biological or larval therapy), has become accepted practice in some wound care centers (Table 8-3).2,4

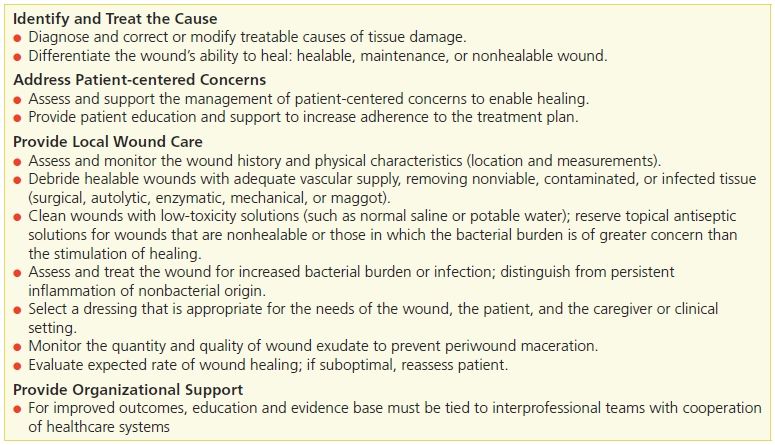

Table 8-3 Best Practices for Preparing the Wound Bed

Reprinted with permission Wound Care Canada, the official publication of the Canadian Association of Wound Care. Available at: http://www.cawc.net, © 2006. All Rights Reserved. Secondary source: Sibbald, R.G., et al. “Best Practice Recommendations for Preparing the Wound Bed: Update 2006,” Wound Care Canada 4(1):15–29, 2006.

Mechanical Debridement

Methods of mechanical debridement include wet-to-dry dressings, hydrotherapy (whirlpool), and wound irrigation (pulsed lavage).1,4,3 Mechanical debridement may be more painful than other debridement methods, and the healthcare provider should always consider patient premedication for pain. Both whirlpool and pulsed lavage (see Chapter 9, Wound Treatment Options) require special equipment and skill. All of the mechanical methods are considered nonselective debridement; that is, they don’t always discriminate between viable and nonviable tissue. Mechanical methods may be harmful to healthy granulation tissue on the surface of the wound and lead to bleeding, trauma, and disruption of the collagen matrix along with the necrotic tissue.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Mechanical debridement may be painful; consider patient premedication for pain.

Wet-to-Dry Dressings

Despite the drawbacks, such as pain and the necessary application up to three times per day, the use of wet-to-dry wound debridement dressings unfortunately remains a common treatment in some healthcare settings. This method involves placing a moist saline gauze dressing on the wound surface and removing it when it’s dry. The removal of the dried gauze dressing facilitates removal of devitalized tissue and debris from the wound bed. However, newly formed granulation tissue and new cell growth are also removed. To prevent pain and to help remove the dry gauze, clinicians often wet the dressing before removal. However, this defeats the purpose of aggressively removing dead tissue. This type of debridement requires significant nursing time, and although the materials may be relatively inexpensive, the overall cost can often be greater than other techniques.

A wet-to-dry dressing can be used when a moderate to large amount of necrotic tissue is present and surgical intervention is not an immediate option. Because of pain and the removal of viable tissue, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has stated in its revised surveyors guidance on pressure ulcers in long-term care that use of wet-to-dry dressings should be limited.19 CMS also states that wet-to-dry dressings should not be used in a clean, granulating wound. Instead, they recommend use of moist wound therapy dressings, which are discussed in chapter 9, Wound treatment options.

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy (or whirlpool) debridement may be indicated for patients with large wounds that need aggressive cleaning or softening of necrotic tissue. It is contraindicated in granulating wounds because it can macerate and injure the wound bed. Hydrotherapy should be discontinued after necrotic tissue has been removed from the wound bed.

Hydrotherapy is performed by putting the patient’s wound in a whirlpool bath and letting the swirling waters soften and loosen dead tissue. This procedure is usually performed in the physical therapy department, with an average treatment duration of 10 to 20 minutes up to twice per day. Operators should carefully monitor the water temperature to prevent burns. The water should be tepid (80°F to 92°F [26.7°C to 33.3°C]) or close to body temperature (92°F to 96°F [33.3°C to 35.5°C]).

This type of debridement may cause periwound maceration, traumatize the wound bed, and put the patient at risk for waterborne infections such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The potential for cross-contamination between patients is also a concern. Both patients and healthcare workers may be exposed to health risks associated with aerosolization. To minimize infection risks, the whirlpool tank must be cleaned thoroughly with an appropriate disinfectant after each use.

Pulsed Lavage

Pulsed lavage debridement is often indicated for patients with large amounts of necrotic tissue and for those in whom other debridement methods are not an option. It is accomplished by using specialized equipment that combines a pulsating irrigation fluid with suction.20 Utilizing pulsed lavage, you can clean and debride a wound at variable irrigation pressures (measured in pounds per square inch [psi]). The pulsatile action and effective wound bed debridement may improve granulation tissue growth. This treatment takes 15 to 30 minutes and should be performed twice daily if more than half of the wound contains necrotic tissue.

Patients may need to be premedicated for comfort before beginning the procedure. Safe and effective ulcer irrigation pressures range from 4 to 15 psi.21 Water pressure control is critical during this procedure. Because fluid is being forced directly at the wound, the risk of driving organisms deep into the wound tissue is a concern. In addition, inhalation of contaminated water droplets or mist is possible for both the clinician and the patient.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Always use appropriate equipment to prevent excess lavage pressure. Wear personal protective equipment to prevent splash injury, including eye and face protectors as well as an impervious gown. Remember to administer pain medication to the patient before the procedure.

Sharp/Surgical Debridement

Sharp/surgical debridement includes the use of a scalpel, forceps, scissors, hydrosurgery devices, or lasers to remove dead tissue.2,4,22 Sharp debridement is considered by many clinicians to be the gold standard of debridement.23 It can cause pain, so a topical anesthetic, such as lidocaine cream or gels, may be required.24 Patients may also need follow-up appointments for serial debridement.

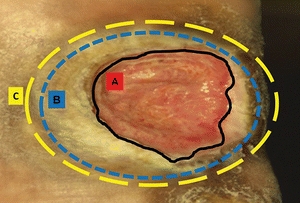

Because viable tissue may also be removed inadvertently with this method, excellent judgment must be used when performing sharp debridement.23–25 The clinician must be able to differentiate where and what to cut, identifying, for example, a tendon versus slough because both are yellow in color23–26 (Fig. 8-4). Clinicians need guidance in discerning the line of demarcation between viable and nonviable keratinocytes at the wound edge. As shown in Figure 8-5, most clinicians can identify the stalled edge of a chronic wound (location A), where the keratinocytes, which are the cells that close the surface of the wound, cannot migrate across the wound bed. Research suggests that the wound edge really extends to location B27,28 and that debriding only to this boundary may be inadequate as it leaves behind impaired cells.27,28 Therefore, adequate debridement of a chronic wound needs to extend beyond the point at which the keratinocytes have lost the ability to move (edge of the callus tissue at location B) to where the cells can move to heal the wound (location C). Clinicians may need to rethink the distance from the wound edge (location A) that they need to debride. Research focuses on an easy way for clinicians to identify how far from the wound edge to perform debridement, based on the pathology of the abnormal keratinocytes at the wound edge.27,28 While this technique is being adapted for clinical use, Endara and Attinger have described a simple clinical technique to stain the tissues with methylene blue dye as a color guide to aid the clinician to do a complete wound debridement.26

Figure 8-4. Differentiating tendon from slough. Performing debridement requires knowing where and what to cut. For example, tendon and slough both are yellow—the clinician must be able to distinguish between them.

Figure 8-5. Margin of debridement. The solid black line (A) indicates a nonhealing edge. The outer blue and yellow broken lines (B and C) indicate two possible margins of debridement. Location B is the edge of the wound, whereas location C is the presumed location of the healing edge of the wound where keratinocytes have the ability to migrate and participate in the wound healing process. Therefore, debride to location C. (Adapted from Tomic-Canic, M., Ayello, E.A., Stojadinovic, O., et al. ”Using Gene Transcription Patterns [Bar Coding Scans] to Guide Wound Debridement and Healing,” Advances in Skin & Wound Care 21(10):487–92, 2008.)

Nonviable surgical debridement must be distinguished from sharp/surgical debridement, which may remove viable tissue on the wound surface to a bleeding base and thus create an acute wound within a chronic wound.1–3,12,23 This procedure is usually performed by experienced physicians or surgeons. In the United States, only physicians can perform surgical debridement in the operating room with hydrosurgery devices. Individual states may allow nurses, physical therapists, and physician assistants with appropriate licensing and training to perform some sharp debridement procedures with a scalpel, forceps, or scissors. Recommendation for conservative sharp debridement for nurses in the USA is written by WOCN29 and for Canada.14

The use of sharp debridement is based on expert opinion and clinical data. Steed et al.30 reanalyzed data from a six-site random controlled trial that tested the use of recombinant human platelet–derived growth factor (rhPDGF) versus placebo in neuropathic diabetic foot ulcers. These authors found significantly higher healing rates in treatment facilities in which more frequent and complete surgical debridement to bleeding tissue was performed rather than simply removal of the periwound callus. The removal of loose bright friable granulation tissue from the surface of an ulcer removes senescent fibroblasts as well as bacteria that may be arranged in biofilms. The wound surface bacteria and callus around the perimeter of the ulcer lead to underlying tissue damage. Surgical debridement is used for adherent eschar and devitalized or dead slough on the wound surface. This method can be selected for acute infected wounds and should be the first choice for wounds demonstrating signs of advancing cellulitis or sepsis. Small wounds may be debrided at the bedside, but extensive wounds—for example, a stage IV pressure ulcer—may require debridement in the operating room. Physicians have reported that the use of hydrosurgery devices has decreased the number of times that maintenance debridement was needed22 (Fig. 8-6). Other authors have described the use of hydrosurgery devices in combination with undiluted Betadine and a bilayer porcine collagen dressing to successfully debride burns.31 Surgical/sharp debridement must be performed with extreme caution in patients taking anticoagulant medications. The medication may need to be held for a short period of time prior to the procedure. Patients with prolonged bleeding may be best treated with other methods of debridement (Figs. 8-7 and 8-8).

Figure 8-6. Hydrosurgery device. Example of one type of device used to remove necrotic tissue. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey Niezgoda, MD.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree