Elizabeth A. Ayello, PhD, RN, ACNS-BC, CWON, MAPWCA, FAAN

Diane K. Langemo, PhD, RN, FAAN

Objectives

After completing this chapter, you’ll be able to:

- state the reasons for performing a wound assessment

- differentiate between partial- and full-thickness injury

- list the parameters of a complete wound assessment

- describe useful photographic techniques for wound documentation

- discuss wound documentation using an electronic medical record and electronic health record.

The Wound

Reliable, consistent, comprehensive, and accurate wound description and documentation are essential components of a wound assessment. Not only does it provide objective data to confirm wound progress, but it can also serve to alert clinicians about wound deterioration.1 Wound description and documentation also enhances communication among healthcare providers, patients, and care settings.1,2 Assessment of wounds is important because several clinical characteristics, such as new or increasing pain, new or increasing cellulitis, new or increasing purulent or nonpurulent drainage, and significant undermining, have been reported to constitute a wound emergency.2 Appropriate assessment and monitoring of wound healing is founded on scientific principles.3

The management of acute and chronic wounds has progressed into a highly focused area of practice, with physicians, nurses, therapists, and other professionals expanding their practice in this challenging arena. Care plans, treatment interventions, case management, and discharge planning, as well as ongoing patient and wound management, are all based on the initial and subsequent wound assessments. The total patient assessment, inclusive of any comorbid conditions and lifestyle, must also be a part of any comprehensive wound assessment. This chapter addresses the key assessment parameters of a patient with a wound admitted to any healthcare setting, including the importance of a history and physical examination, how to assess a wound, essential practice points, and examples of accurate and thorough documentation tools.

A wound is a disruption of normal anatomic structure and function.4 Wounds are classified as either acute or chronic. Acute wounds can result from trauma or surgery. According to Larazus and colleagues,4 acute wounds proceed through an orderly and timely healing process with the eventual return of anatomic and functional integrity. Chronic wounds, on the other hand, fail to proceed through this process and lose the cascade effect of wound healing and sustained anatomic and functional integrity. Stated simply, wounds may be classified as those that repair themselves or can be repaired in an orderly and timely process (acute wounds) and those that don’t (chronic wounds).4 See Chapter 5 for a more detailed description of wound healing. In the United States, the current Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) definition of a chronic wound includes a time frame of greater than 30 days’ duration for complete healing.5

The etiologies or causes of the wound must be determined before appropriate interventions can be implemented. This is especially important as many wounds have mixed etiologies. Ensuring a differential diagnosis right is not always easy, but learning the typical characteristics of a wound type can be helpful. Wounds may have a surgical, traumatic, neuropathic, vascular, or pressure-related etiology. For example, an acute wound caused by a bite (animal, insect, spider, or human) requires a different care plan than a wound caused by a burn. A patient who has an animal bite may require additional testing to rule out damage to nerves, tendons, ligaments, or bone, as well as determination of rabies or rabies vaccination status of the animal and the need for tetanus immunization.6 The pathologic etiology will provide the basis for additional testing and evaluation to start the wound assessment process and basis for correct classification (see Practice Point: The nine C’s of wound assessment).

Practice PointThe Nine C’s of Wound Assessment

Practice PointThe Nine C’s of Wound Assessment

Wound assessment is needed for the following nine reasons:

- Cause(s) of the wound

- Clear picture of what the wound looks like

- Comprehensive picture of the patient

- Contributing factors

- Components of the wound care plan

- Communication to other healthcare providers

- Continuity of care

- Centralized location for wound care information

- Complications from the wound

Initial Patient Assessment

Obtain a thorough history and a complete physical examination on every patient admitted into your care. Obtaining a patient history provides information on relevant disease processes, comorbidities, medications the patient is taking, and family history of conditions that can impact the etiology and potentially the treatment and healing of the wound. In addition, the patient history may reveal information that explains previous wound healing concerns, infection, nutritional status, and other core information needed to develop the plan of care. A detailed patient medical and social history should direct additional questioning on any abnormal lab findings as well as a history of diabetes, vascular conditions, or an immune-compromised state. Assess pain and the patient/family knowledge regarding wounds. Therapies received as part of a prior health condition, such as radiation at the site of a wound, as well as history of a pressure ulcer increases risk to that area, are also important factors that can contribute to impaired healing and delay appropriate management strategies1 (see “Radiation wounds” in Chapter 23, Palliative Wound Care). Use the assessment data to determine whether the wound is healable, maintenance, or nonhealable.7

Family support and patient and family functional abilities should be evaluated as well. Involving other services and/or departments (e.g., social work, case management, pastoral care) early in the care planning process is crucial to developing a comprehensive plan of care for the wound patient. Case managers can be invaluable in determining the continuity of care across healthcare settings by asking the following questions during the initial assessment:

- What are the patient’s values and goals of care?

- Can the patient care for himself or herself?

- Is there a caregiver available to assist with care after discharge?

- Can the patient change his or her own dressings?

- Who will put on and help remove compression stockings?

- Can the patient afford to purchase the necessary wound products/items?

- Does the patient/family know how to care for the stockings or other equipment?

Asking these questions is vital to conducting a comprehensive assessment of a patient with a wound.

Physical Examination

A head-to-toe physical examination should be performed. Evaluation of the skin, including any skin folds, pressure points, healed pressure ulcer sites, old scars or lesions, indications of previous surgeries, and the presence of vascular, neuropathic, or pressure ulcers, should be noted. The appearance of the skin, nails, and hair on the extremities should be assessed. Appraisal of skin color, temperature, capillary refill, pulses, and edema are also important elements of a thorough physical examination (see Chapter 4 Skin: An Essential Organ).

Different types of wounds require different considerations. Dehisced surgical wounds may have opened due to an infection or may heal poorly due to underlying disease processes, current medications (such as steroids), or malnutrition. Hemosiderin staining (reddish-brown color), caused by the chronic leakage of red blood cells into the soft tissue of the lower leg, is a classic sign of venous insufficiency and often seen in a person with a venous ulcer. If not managed with compression, this leakage often leads to venous ulcers. Arterial ulcers often present with the classic signs of hair loss, weak or absent pulse, and very thin, shiny, taut skin. Neuropathic ulcers require intense evaluation to determine the extent of the neuropathy. Patients with diabetes are prone to callus formations and pressure points even when off-loading interventions are in place. Both are easily noted on examination (Fig. 6-1).

Figure 6-1. Hemosiderin deposit.

In persons with darkly pigmented skin, early detection of ulceration that relies only on visual inspection by the clinician to note erythema and color changes (such as a stage/category I pressure ulcer) remains a clinical challenge. The lack of a tool to help clinicians detect erythema in darkly pigmented skin hampers early detection of tissue injury. In a study in which 28 of 56 subjects had darkly pigmented skin, the authors showed that use of multispectral images of the ulcers resulted in algorithms that enhanced detection of erythema in darkly pigmented skin.8 Assess for differences in skin temperature at the opposite site, skin tenderness, changes in tissue consistency, and pain.3

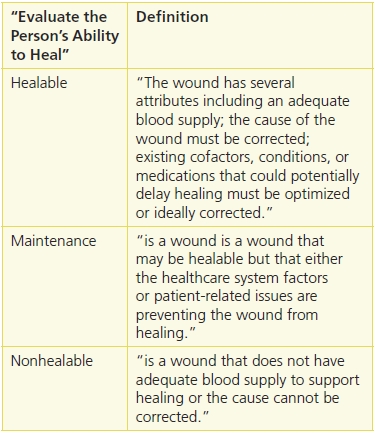

A comprehensive patient examination will reveal areas of concern for wound development and can pinpoint wound origins as well as why healing is not progressing in some wounds. Based on the comprehensive assessment and the determination as to whether a wound is healable, maintenance, or nonhealable, appropriate goals and treatment plan can be developed7,9 (see Table 6-1). Developing realistic goals and care plans, performing regular follow-up examinations, and ensuring patient adherence to the plan of care are all key markers for successful outcomes (see chapters on specific wound types for more details).

Table 6-1 Healability of a Wound

Source: Sibbald, R.G., Goodman, L., Woo, K.Y., et al. “Special Considerations in Wound Bed Preparation 2011: An Update,” Advances in Skin and Wound Care 24(9): 415–36, quiz 436-38, 2011.

Wound Assessment and Classification

Wound assessment—a written record and picture of the current status and progress of a wound—is a cumulative process of observation, data collection, and evaluation. As such, it’s an important component of patient care. A wound assessment includes a record of your initial assessment, ongoing changes in the wound bed and periwound area, and treatment interventions. The initial assessment serves as the baseline for future comparisons, with ongoing assessments occurring at least weekly and when significant changes occur throughout the healing process.3

Practice Point

Practice Point

Because a wound can change rapidly, it is important to assess wounds for changes that could signal the need to modify treatment.3

Although the frequency of wound assessment is often determined by individual agency or institutional guidelines, treatment modalities, regulatory guidelines, and wound characteristics also play a role in determining assessment frequency.10 According to the most recent international guidelines, pressure ulcers should be evaluated at a minimum on admission, weekly, and with any signs of deterioration.3 Frequency of assessment is also determined by wound severity, the patient’s overall condition, the patient’s environment, and the goals and plan of care.10 Acute care patients often receive wound assessments daily or with each dressing change. In long-term care facilities, wounds must be assessed on admission, with each dressing change, and at least weekly.11 Home care assessments are usually based on the frequency of the home visits but often occur weekly and/or with each licensed nurse visit. Regardless of the setting, however, the frequency of assessments should be determined by the wound characteristics observed at the previous dressing change, the significance of wound changes from one assessment to the next, as well as on the physician’s or other practitioner’s orders. Patient interventions should be implemented based on the baseline and subsequent wound assessment data (see Practice Point: When to reassess a wound).

Practice PointWhen to Reassess a Wound

Practice PointWhen to Reassess a Wound

Assessment provides indicators of successful treatment interventions and attainment of achievable outcomes and guides decisions about product changes. Reassess the patient’s wound:

- before and after any surgical or specialized procedures

- weekly for a pressure ulcer3

- if the wound noticeably deteriorates

- if the wound becomes odorous, has new purulent exudate, or becomes more painful

- upon observing any other significant change in the condition of the wound, including at time of transfer or discharge

- after the patient has returned from another facility.

Although wound assessment needs to be in compliance with the regulatory requirements specific to the care setting, no written standard exists outlining the type and amount of information to include in a wound assessment. Likewise, no single documentation chart, tool, or electronic medical record (EMR) has been designated as the most effective. Banfield and Shuttleworth found that wound assessments were documented significantly more frequently when an assessment chart or form is used and that using a chart or form improves the nurses’ assessment skills.12 The best assessment form is one that is used consistently by the facility’s staff. Forms that can be completed easily and quickly are more likely to be used on a regular basis. If the staff finds a form too long or difficult, that form is less likely to be used.

A complete, comprehensive initial assessment of the individual with a wound includes complete medical and social history, patient/significant other’s goals of care, factors that may affect healing, a vascular assessment with extremity wounds, laboratory assessments as needed, nutritional status, pain, risk for developing additional wounds, psychological health and cognitive status, social and financial support systems, functional capacity (related to repositioning, posture, need for assistive equipment or personnel), pressure redistributing ability, support surface availability, knowledge of prevention and treatment, as well as ability to adhere to the treatment plan.3 A minimal wound assessment should include a thorough assessment of the whole patient, identification of the cause of the wound, and wound characteristics such as type of wound, location, size, depth, exudate and tissue type(s) present, and periwound condition.

Wounds can be classified using several different approaches. The partial- versus full-thickness model is used primarily by physicians and clinicians for wounds other than pressure ulcers. Damage to the epidermis and part of the dermis constitutes a partial-thickness wound. Abrasions, skin tears, blisters, and skin-graft donor sites are common examples of partial-thickness wounds. Full-thickness wounds extend through the epidermis and dermis and may extend into the subcutaneous tissue, fascia, and muscle. Partial-thickness wounds heal by resurfacing or reepithelialization. Full-thickness wounds heal by secondary intention through the formation of granulation tissue, contraction, and, finally, reepithelialization, which of course requires a longer time period for healing.5

Pressure ulcers and neuropathic ulcers have their own staging and classification systems to indicate the depth of injury and healing methods. Use the specific system for the type of wound (see Chapter 13, Pressure Ulcers, and Chapter 16, Diabetic Foot Ulcers, and Chapter 4 section on skin tears, for more information).

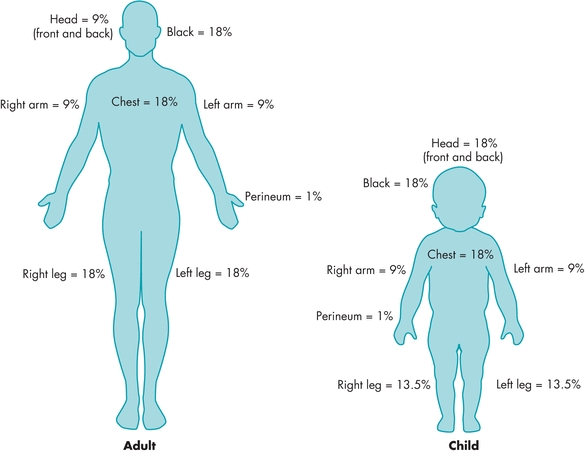

Assessing the severity of a burn is a two-part process. Burn injuries are described by the extent of the body burned using one of several methods for estimating burn size, such as the rule of nines13 or the Lund and Browder Chart14 (Fig. 6-2). The depth of a burn injury is described by clinical observation of the anatomic layer of the skin involved (e.g., superficial, partial-thickness, full-thickness, or subdermal burns).

Figure 6-2. The rule of nines. The rule of nines estimates the amount of body surface that has been burned. In adults, the body is divided into sections of 9% or multiples of 9%. The percentages used in the rule of nines differ between adults and children.

Obviously, there are many parameters to consider when performing a comprehensive wound assessment. Each clinical agency needs to develop a protocol that all clinicians should learn and follow to ensure consistency of assessment and documentation. Whether using stage/category, or partial- and full-thickness terminology, the one constant is clinical assessment. Assessment data give the healthcare provider a mechanism by which to communicate, improve continuity among disciplines, and establish and modify appropriate treatment modalities.

Elements of a Wound Assessment

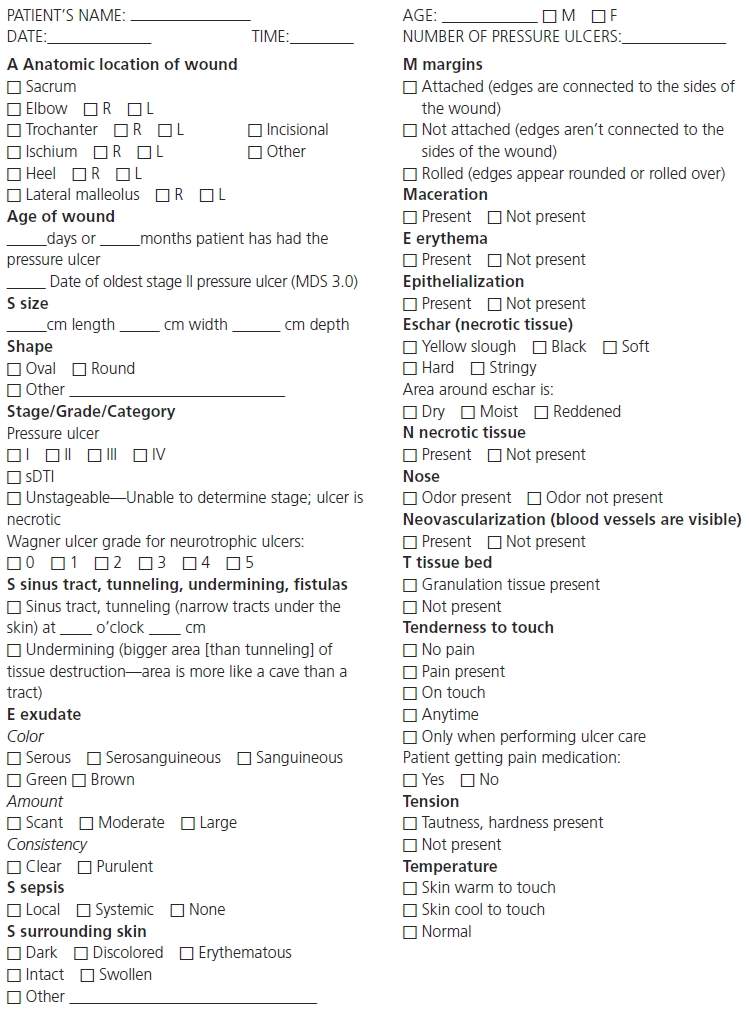

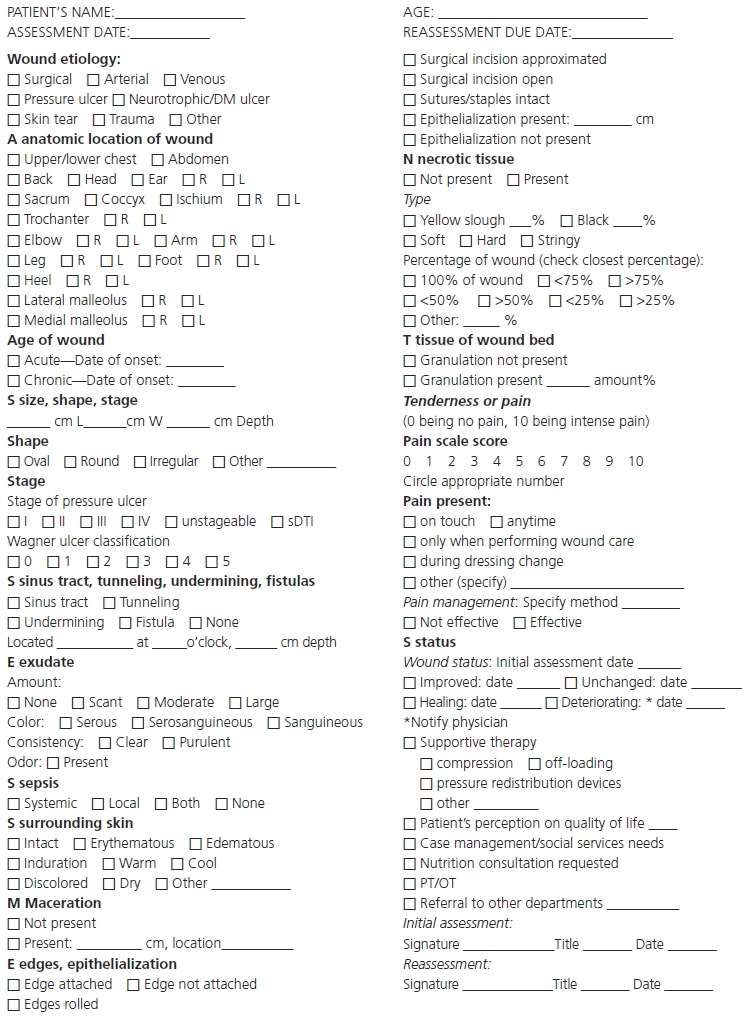

In 1992, Ayello developed a mnemonic for pressure ulcer assessment and documentation15 (Boxes 6-1 and 6-2). The mnemonic has been adapted for use with any type of wound to provide a thorough look at the parameters that complete and enhance an assessment. It provides a support structure for clinical decision making regarding ongoing assessment and reassessment and may be used in any practice setting according to the guidelines set up by your facility. This assessment chart may be used daily, weekly, or monthly. It’s simple, fast, and can be further adapted to fit individual use.

Box 6-1 Pressure Ulcer ASSESSMENT Chart

© 2011, Baranoski, Ayello. From Ayello, E. “Teaching the Assessment of Patients with Pressure Ulcers,” Decubitus 5(7), 53–4, July 1992.

Box 6-2 Wound ASSESSMENTS Chart

© 2011, Revised Baranoski & Ayello.

Location and Age of Wound

Wound location should be documented using the correct anatomical terms—for example, right greater trochanter rather than right hip. Include an anatomical figure or diagram of the human body, with the wound’s location noted in your assessment record to provide complete admission documentation. If there are two or more wounds near one another, they should be labeled and numbered for clarity (e.g., 1a, 1b, etc.). It is particularly important to note how long the patient has had the wound, especially since CMS now requires that the date of the oldest stage II pressure ulcer be recorded on Minimum Data Set 3.0 (M0300B.3).16 Are you dealing with a new, acute wound or a wound that has failed to heal for several weeks or months? Time isn’t the sole determinant of acute versus chronic wound status. Although 30 days is often used for designation as chronic status, the more important criterion is whether or not the wound is making progress toward healing.5,16

In addition to wound duration, documentation of the etiology of the wound, if known, is important. For example, if a patient reported that she spilled hot coffee on her amputated stump, causing a blister that evolved into a full-thickness wound due to trauma and insufficient arterial supply, it would be incorrect to classify the wound as a pressure ulcer. It is not unusual for an individual with diabetes mellitus to have a neuropathic/vascular ulcer or to have multiple ulcers of more than one origin.

Wound Size and Stage/Category

The joint National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP)–European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (EPUAP) classification system3 is only intended for use in staging/categorizing pressure ulcers. It was revised in 2009 to include four numerical stages with two additional categories for use in the United States that incorporate suspected deep tissue injury and unstageable ulcers into their own separate categories.17 The staging/categorization system addresses the depth of tissue damage in numerical stages/categories I through IV. Any pressure ulcer covered with eschar or necrotic tissue is unstageable, including in long-term care where CMS now requires that it be documented on MDS 3.0 under the unstageable section M0300F in the United States.16,18 Reverse staging is no longer required in the long-term care setting16,18 and is never recommended19 (see Chapter 13, Pressure Ulcers).

Partial-thickness wounds heal fairly quickly (days to weeks) as they involve the epidermis and extend into, but not through, the dermis. Full-thickness wounds penetrate through the fat and involve muscle, tendon, or bone and take longer to heal (Fig. 6-3). Use the correct classification/staging system for the specific wound type, for example, Meggitt-Wagner for diabetic ulcers (see Chapter 16, Diabetic Foot Ulcers) or International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) for skin tears (see Chapter 4, Skin: An Essential Organ).

Figure 6-3. Necrotic, unstageable pressure ulcer. Shown here is a pressure ulcer that’s unstageable because its base is covered with eschar. Be sure to measure the pressure ulcer’s length, width, and percent and type of necrotic tissue. Document your findings.

Practice Point

Practice Point

Even though an ulcer is necrotic and unstageable, you still need to document the wound size for length, width, percent and type of tissue present, exudate, and odor.

Wound Measurement

Measurement of a wound is an important component of wound assessment and provides valuable information on wound progression or nonprogression as well as assessment of the effectiveness of clinical interventions. Wound measurement is particularly important in determining clinical effectiveness for research purposes. Consistency and accuracy in how the wound is measured are important for meaningful comparisons to determine changes in the wound over time and for comparing the effectiveness of various treatments. Consistency is best assured when the agency develops and disseminates a protocol for wound measurement that staff can follow. It is also important to use consistent patient positioning every time a wound is measured.3

Wound measurement methods can be simple or sophisticated, two-dimensional (wound surface area) or three-dimensional (wound volume). A variety of systems are used to measure wounds and assess healing. These include wound tracing, width and length measurements, computerized wound-documenting systems (which can be one, two, or three dimensional), and digital photography.1,20,21 A new handheld portable device that combines a digital camera with a scanner unit that plugs into a standard personal digital assistant has reportedly been useful in the community setting for assessment and documentation of venous and diabetic ulcers.1 The WoundVision Scout is a portable, handheld device that can photograph the wound for computerized measurement and documentation.22 Changes in wound measurements, such as a decrease in size, are used as an indicator of healing. Surgical incisions can be measured using length (e.g., “incision line is 8 cm long”). Wounds should not be measured using objects, such as a dime or half-dollar, but rather should be measured in centimeters or millimeters depending on the size of the wound.

Area

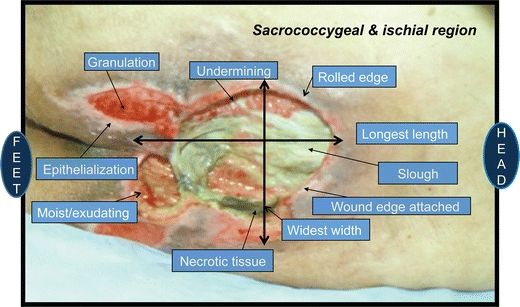

The simplest and most common method of wound measurement is the linear method using a paper or plastic ruler marked in centimeters and millimeters. The NPUAP Position on Wound Area Measurement, outlined in a 2008 study by Langemo and colleagues,21 is to measure the greatest head-to-toe length and the greatest side-to-side width perpendicular (90-degree angle) to each other.21,23 If this method is used consistently, then measurements over time should become more reliable and comparable (Fig. 6-4). Linear measurement is inexpensive, readily available, causes little to no discomfort, and is used frequently by most clinicians.3,21 However, use caution with this method, as it assumes that the wound area is a rectangle or square, which is rarely ever the case, and nearly always overestimates the size of the wound.24 Regardless of which method is used, what’s most important is to have an agency protocol that the staff understands and that is being implemented consistently.

Figure 6-4. Wound terminology. Using current terminology is imperative for accurate assessment. This photograph labels the wound’s characteristics as well as its length and width.

Another way to measure area is to multiply length by width in square centimeters (cm2). This adds a third dimension of depth, which is then added to the linear measurement if desired.24,25 If the wound is open, depth can be assessed by placing either a clean cotton-tipped applicator or a centimeter measuring device into the deepest part of the wound, marking it, and then measuring it upon removal (Fig. 6-5).

Figure 6-5. Determining wound depth. The depth of a wound can be measured by placing a sterile, premoistened (with normal saline or sterile water) cotton-tipped applicator into the wound and comparing the marked area against a centimeter measuring device.

Planimetry is a method where a wound tracing is made on metric graph paper with a 4-cm or 8-cm grid. The completed squares, within the traced wound edges, are then counted to yield an approximate area in square centimeters.26 Minimal training is needed to use this method, the acetate tracing medium is inexpensive and disposable, and the wound area can be determined immediately.24

The wound area can also be measured noninvasively by stereophotogrammetry (SPG), using a digital camera and computer software. A target plate is placed within the plane of the wound to be photographed. The digital photo is then downloaded to the computer screen where the wound edges are traced, along with the length and width, using a computer-pointing device or mouse. The software automatically calculates the area as well as the length and width.24 A color picture of the wound along with the measurements taken during each visit can be printed on a chart sheet for the patient record. This method allows for accurate, reproducible measurements of irregular wounds and is noninvasive.24,27

The WoundVision Scout, a handheld, portable device, can easily measure wound L and W as well as area thermal (infrared) and visual wound imaging. The Scout is a medical imaging clinical tool designed to photograph and measure area of a wound. It can be used to monitor change in wound size over time.22

Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-Based Practice

Using SPG to measure wounds is the most accurate and reliable method. Digital planimetry has fairly good reliability.24,27

Volume

As most wounds extend below the skin surface, they are three dimensional, generally irregular, and, at times, cone shaped. To that end, volume becomes an important variable and needs to be calculated. The most commonly used technique to assess wound volume is to measure the three dimensions of length, width, and depth and multiply those measurements by one another (L × W × D = volume cm3).25 Caution should be used, however, as this equation assumes that the base and surface area are the same size, which is generally not the case. The net effect is overestimation of wound volume.

Other techniques include molds, fluid instillations, the Kundin device, and SPG. Molds and fluid installations are imprecise and time consuming, are uncomfortable for the patient, and can potentially contaminate the wound.26 The Kundin device is a plastic-coated, disposable, three-dimensional gauge with three arms for measuring length, width, and depth.28 Wound volume is calculated via a mathematical formula that assumes the shape of the wound lies somewhere between a cylinder and a sphere.28 Measuring volume using the Kundin device is a convenient, relatively inexpensive, user-friendly technique.28 As mentioned previously, SPG measures the depth and area of a wound and inputs that information into software that calculates wound volume using the Kundin device formula. In one study, SPG was found to have the greatest reliability and least error of measurement.25 When the Kundin device and SPG were compared using wound models, SPG was the more accurate method. However, more research is needed. The key is to select and implement a consistent method to measure depth.3

Sinus Tracts, Undermining, and Fistulas

Sinus tracts/tunnels, undermining, and fistula formation delay the healing cascade. Intervening early with the appropriate medical and/or surgical and/or nursing actions is paramount to healing these complicated wounds.

Sinus Tracts

A sinus tract (or tunnel) is a course or path of tissue destruction, sometimes called a “tunnel,” occurring in any direction from the surface or edge of a wound. It results in dead space with a potential for abscess formation. A sinus can be distinguished from undermining in that it involves only a small portion of the wound edge; undermining involves a significant portion of the wound edge.17 The sinus or tunnel has a potential for abscess formation, further complicating the healing process. Sinus tracts are common in dehisced surgical wounds and may also be present in neuropathic wounds, arterial wounds, and pressure ulcers. Documenting sinus tracts is an important element in assessment because it enables the clinician to evaluate potential treatment interventions and to identify reasons for nonhealing. Treatment interventions involve loosely packing the dead space with an appropriate dressing to stimulate granulation tissue production and the contraction process. Document what goes into the tract to see that it is removed during dressing changes. The goal is to close the sinus tract first, while allowing the outside of the wound to remain open and fully heal.

Measurement of a sinus tract can be made by inserting a sterile, premoistened cotton-tipped applicator, a centimeter measuring device, or a gloved finger into the bottom or end of the tract, marking it, and then measuring it upon removal. This must be done very carefully to avoid injury during measurement (Fig. 6-5).

Undermining

Undermining is tissue destruction that occurs around the wound perimeter underlying intact skin; in these wounds, the edges have pulled away from the wound’s base (Fig. 6-6). Pressure ulcers that have been subjected to a shearing force often present, with undermining in the area of the greatest shear. Undermining is also seen when the opening of the wound is smaller than the affected tissue below the dermis and in desiccated wound beds.

Figure 6-6. Undermining, as shown, is tissue destruction that occurs around the wound perimeter underlying intact skin.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree