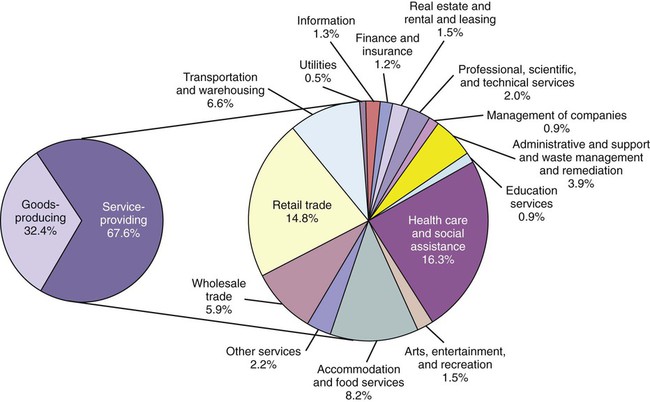

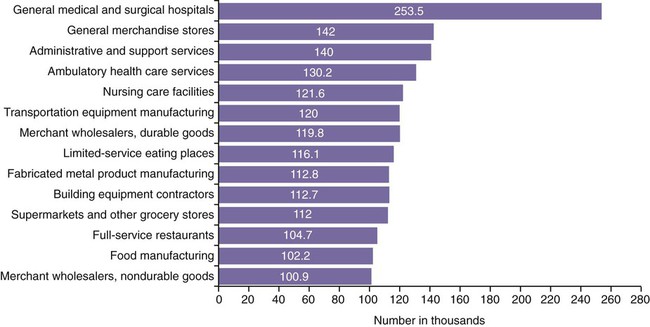

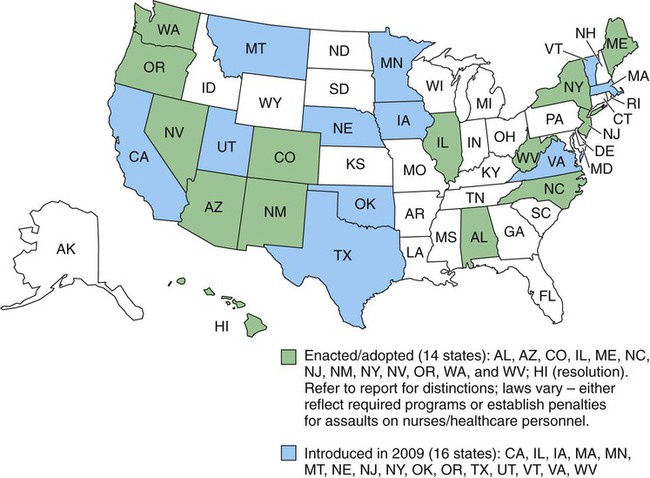

• Categorize the types of violence/incivility that may occur in the workplace. • Analyze risk factors for potential violence or disruption. • Describe guidelines for preventing workplace violence and incivility. • Evaluate your organization’s plan for preventing workplace violence and incivility. • Evaluate interventions that help prevent horizontal violence and incivility. As part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducts research and makes recommendations to prevent work-related illness and injury. NIOSH works with industry and labor organizations to understand and improve worker safety and health. NIOSH (2002) defines workplace violence as “violent acts (including physical assaults and threats of assaults) directed toward persons at work or on duty.” The definition of violence includes overt and covert behaviors ranging from offensive or threatening language to homicide. In recent years, additional descriptions of other forms of workplace violence have been added. Horizontal violence or lateral aggression has been used to describe aggressive and destructive behavior of co-workers against each other. Other terms associated with this type of violence include bullying and interpersonal conflict. These behaviors exist in what has been termed toxic workplaces. Incivility includes a wide range of behaviors from ignoring, to rolling one’s eyes, to yelling, and eventually to personal attacks, both physical and psychological. Both types of workplace violence are addressed in this chapter and are referred to as violence. The true scope of workplace violence in health care is difficult to determine. The main source of data for workplace violence and injuries is the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Fatal and nonfatal occupational injury statistics are collected by the BLS in two major categories: goods-producing and service-providing industries. In a 2006 BLS report of service-providing organizations, healthcare and social assistance organizations had the highest percentage of reported nonfatal injuries (Figure 25-1). Because the reporting category includes both healthcare and social assistance organizations, accurate data for health care alone are hard to determine. In another BLS summary report released in 2007 (Figure 25-2), more specific analysis indicated employees working in general medical and surgical hospitals had the highest number of nonfatal occupational injuries in private-sector industries. Ambulatory health services and nursing care facilities appeared fourth and fifth in frequencies. When combined, the disproportional incidence in these three healthcare settings is cause for concern. In addition, 114 fatal injuries were reported in preliminary BLS data for health care in 2007. Although this number is a concern, the incidence of fatal injuries is low when compared with the combined number of fatalities or for other types of industries. There are concerns that the true rate is much higher because many incidents are not reported, especially when violence does not result in a physical injury or is verbal in nature such as intimidation or bullying. Underreporting in health care is thought to be related to a perception within nursing that assaults with or without injuries are “part of the job.” One survey of nurses in Minnesota reported that the annual rate of physical and non-physical assaults on nurses per 100 respondents was 13.2 (Nachreiner, Gerberich, Ryan, & McGovern, 2007). According to Hader (2008) in a survey conducted by Nursing Management, 80% of the 1377 nurse respondents from the United States and 17 other countries reported they had experienced some form of violence within the work setting (Box 25-1). Verbal rather than physical forms of violence were reported most often. According to the survey, the perpetrator was a patient 53.2% of the time, with nurse colleagues a close second at 51.9% of the time. Next in the ranking were physicians (49%), visitors (47%), and other healthcare workers (37.7%). Nurses observed their colleagues being the primary target of this violence (79.7%) and had personally been the target (56.1%). Many earlier studies with similar findings demonstrate the need to examine the causes of workplace violence and develop programs and strategies to improve personal safety in the work environment. In particular, attention needs to be paid to the causes and remedies for lateral violence issues. Although no national legislation or federal regulations specifically address the prevention of workplace violence, the Occupational Safety & Health Administration (OSHA) has published voluntary guidelines for workers in healthcare and several other high-risk professions. Although employers are not legally obligated to follow these guidelines, the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSH Act) (1970) mandates that, in addition to complying with hazard-specific standards, all employers have a general duty to provide their employees with a workplace free from recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm. An organization can be cited if its leaders fail to address such hazards. Because healthcare workers are at increased risk, OSHA (2004) developed Guidelines for Preventing Workplace Violence for Health Care and Social Service Workers to assist healthcare organizations in developing violence prevention plans. Several states are also enacting or developing laws, standards, or recommendations that address healthcare workplace security and safety. Many of these laws have been created with strong support from state-based nursing organizations with support from the American Nurses Association (ANA) and other professional healthcare organizations (ANA, 2009). A few states have passed laws that enhance criminal penalties on crimes committed against licensed or certified health professionals. Many other states have or are working on legislation requiring healthcare organizations to have a workplace violence prevention plan (Figure 25-3). The Joint Commission (TJC) (2008) has strengthened requirements in their Leadership standards for dealing with disruptive behavior. Citing studies that suggest intimidating and disruptive behaviors contribute to poor patient satisfaction and preventable adverse outcomes, the standards calls for codes of conduct and processes for managing such behaviors. These standards became effective in January 2009. Our knowledge of the scale of workplace violence remains incomplete because no consistent system of data collection exists. Data regarding the less severe forms of workplace violence are particularly sparse. Even less clear is the financial toll workplace aggression exacts on businesses. A Workplace Violence Research Institute (1995) study estimated the aggregate cost of workplace violence to U.S. employers to be more than $36 billion as a result of expenses associated with lost business and productivity, litigation, medical care, psychiatric care, higher insurance rates, increased security measures, negative publicity, and loss of employees. Pearson and Porath (2009) suggest that estimates of cost should consider how many times people report they are sick when they are really avoiding bad behavior and decreases in productivity because employees no longer feel comfortable in the environment. These costs mount rapidly. Researchers (Hartley, Biddle, & Jenkins, 2005) from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) have attempted to determine the cost of the most extreme workplace violence using a model that calculates direct and indirect costs of workplace fatalities, including medical expenses and lost earnings. NIOSH estimated the average mean cost of a workplace homicide incident, from 1992 to 2001, to be $800,000. The total cost of workplace homicides during this same period totaled nearly $6.5 billion. Studies have yet to capture the full cost of workplace violence in its many forms. More measurement is also needed to assess the cost and effectiveness of known intervention strategies. Since 1990, the University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center (IPRC) has been one of 11 injury “Centers of Excellence” funded by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, a branch of the CDC. Workplace violence has been one of their research focus areas (2001). The University collects and uses epidemiologic data on groups at high risk in order to develop prevention strategies and training to control and prevent injuries. In their investigations, they categorize workplace violence into four types (Box 25-2). Although anyone working in health care is at risk for becoming a victim of violence, those with direct patient contact are at higher risk. NIOSH (2002) reports that healthcare workers in hospitals, specifically those in the emergency department, are at particular risk. Violence is also a frequent occurrence in psychiatric and geriatric settings. Unlike in other settings, hospital violence differs in that it is usually the result of patients or their family members feeling frustration or anger. This is usually related to feelings of vulnerability, stress, and loss of control that accompany illness. Many factors have been identified that can increase the risk for violence erupting in healthcare facilities. Risk factors identified in OSHA’s Guidelines (2004) are listed in Box 25-3. Similar to the nursing process, prevention of workplace violence begins with a systematic assessment. Assessing risk and planning for prevention of workplace violence call for input and expertise from a variety of staff. A risk assessment based on a multidisciplinary team approach to workplace violence prevention is often the most effective. A team with representation from administration, staff, security, facilities engineering, human resources, legal counsel, and risk management is needed to address risks from all perspectives. A worksite assessment involves a step-by-step, common-sense look at the facility and the surrounding areas for existing problems and potential hazards. OSHA’s Guidelines (2004) provide a comprehensive assessment with checklists and forms developed by the ANA to assist with the process. These are helpful to managers and leaders who are not familiar with this type of assessment (Box 25-4). When looking at possible threats or hazards, those from within an organization also must be considered. Determining if current employees pose a danger in the workplace is a critical factor that is often overlooked. In addition to personal and psychological factors, behaviors can be observed in employees that may be related to violence or aggression in the workplace (Paludi, Nydegger, & Paludi, 2006). The most obvious of these is a previous history of aggression and substance abuse. Screening potential employees through drug testing, background checks, and references can help reduce these risks. Paludi et al. (2006) also advise of warning signs that can alert employers of problems with current employees that warrant intervention to prevent a violent incident. Organizational conditions or outcomes may magnify the potential for violence to erupt. This includes prolonged high levels of stress or factors that create what is known as a toxic workplace environment. Rapid change, layoffs, changes in schedules and workloads, or wage freezes could have this effect. The employment situation with the highest potential to create this kind of stress is the firing or layoff process. Most organizations have specific protocols that deal with the process of terminating employees, because firing is cause for strong emotions that can increase the potential for violence. As a manager, you may be responsible for staff terminations. The goal always is to conduct the process in the most professional manner possible, although organizational rules may specify a detailed procedure. A few tips on how to prepare for this potentially problematic situation are provided in Box 25-5. Horizontal or lateral violence describes a wide variety of behaviors, from verbal abuse to physical aggression between co-workers. This term, though commonly used, may be limiting because it suggests the violence is perpetrated between those at the same level of authority. It may be better termed relational aggression (Dellasega, 2009), which can occur between people at different levels. This includes bullying behavior and intimidation. Horizontal violence or bullying is used in this section because these are terms common in the literature. Horizontal violence and its effects have been reported in nursing literature for more than 20 years. In a review of five research studies on horizontal violence, researchers (Woelfle & McCaffrey, 2007) found that horizontal violence is experienced by not only student nurses but also the novice and veteran nurses. Many of the research reports found infighting and a general lack of support of nurses for each other to be common occurrences. The studies also indicate that new graduates were likely to experience horizontal violence, which resulted in high absentee rates and thoughts of leaving nursing after their first year. This caused the researchers to ask this question: How can nurses treat patients kindly and give them the respect they need when they treat each other so poorly? In light of the looming nursing shortage, these consistent findings among nurses were cause for concern. Many theories exist as to why horizontal violence exists in nursing, ranging from nursing’s traditional hierarchical structure, to oppression of nursing as a profession, to feminism (Farrell, 2001). However, it is also noted that workplace aggression is common in other professions and is most likely the result of a complex myriad of individual, social, and organizational characteristics (Farrell, 2001, Hutchinson, Vickers, Jackson, & Wilkes, 2006). Regardless of the reasons why it happens, the concerns are that impaired intrapersonal relationships between nurses at work can cause errors, accidents, and poor work performance (Farrell, 1997) and may play a significant role in attrition (Johnson, 2009). In a survey on workplace intimidation published by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (2003), almost half of the 2095 respondents recalled being verbally abused when questioning or clarifying medication prescriptions. This intimidation played a role in not questioning an order as a way of not directly confronting the prescriber. The results of the survey had professional healthcare and nursing organizations issue calls to action to address all types of workplace violence in the interest of promoting a safe and respectful work environment that promotes the delivery of high-quality care instead of threatening it. Shortly after the publication of the release of the Institute’s report, the International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2006) published a position statement on healthcare workplace violence. The ICN also asserted the following: In 2008, the Center for American Nurses published a position paper stating there is no place in a professional practice environment for lateral violence and bullying among nurses or between healthcare professionals. These disruptive behaviors are toxic to the nursing profession and have a negative impact on retention of quality staff. Horizontal violence and bullying should never be considered normally related to socialization in nursing nor be accepted in professional relationships. The statement goes on to assert that all healthcare organizations should implement a zero tolerance policy related to disruptive behavior, including a professional code of conduct and educational and behavioral interventions to assist nurses in addressing disruptive behavior. See the Literature Perspective on p. 506. A number of other state and national nursing organizations also have issued statements regarding the detrimental effect of disruptive behavior on both patients and nurses and have called for solutions to address the problem. TJC (2008) proposed a revision in its standards for disruptive behavior, identifying manifestations of abuse and violence in the workplace and providing avenues for ending this phenomenon. With professional groups calling for change from within nursing and accreditation groups calling on administration to fix problems, we must examine how to implement a change.

Workplace Violence and Incivility

Introduction

Defining Workplace Violence/Incivility

Scope of the Problem

Ensuring a Safe Workplace

The Cost of Workplace Violence

Prevention Strategies

Types of Violence

Risk Assessment

Firing Right

Horizontal Violence: The Threat from Within

Workplace Violence and Incivility

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access