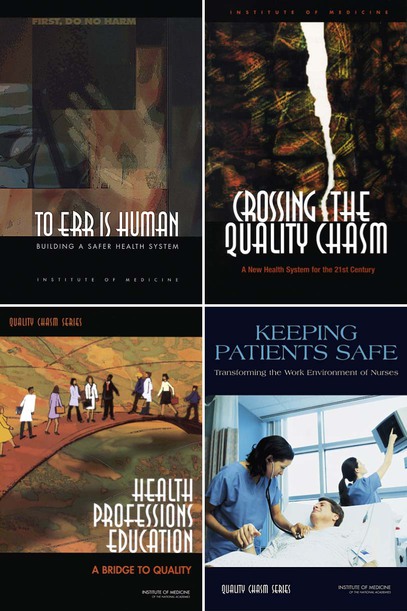

• Identify the key organizations leading patient safety movements in the United States. • Value the need for a focus on patient safety. • Apply the concepts of today’s expectations for how patient safety is implemented. In Chapter 1, the concepts of leading and managing were presented. The question is, however, leading for what? No issue is more prominent in the literature or in healthcare organizations than the concern for patient safety. Although many other aspects of health care are discussed, they all center on patient safety. Many factors and individuals have influenced the nursing profession’s and the public’s concern about patient safety, but the seminal work was To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (2000), produced by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). From that report through the 2005 publication, Preventing Medication Errors, the IOM focused its work on multiple issues surrounding patient safety. Even more popularized publications, such as How Doctors Think (Groopman, 2007) and The Best Practice: How the New Quality Movement is Transforming Medicine (Kenney, 2008), show how important the basic building block of quality—patient safety—is. This focus fits well with the basic patient advocacy role that nurses have supported over decades. This next report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, was released the subsequent year (IOM, 2001). The intent of this second book was to improve the systems within which health care was delivered; after all, the first report identified that systems rather than incompetent people were the major concern. The report spelled out six major aims in providing health care, as shown in Box 2-1. The report went on to acknowledge elements of care that nurses commonly value. For example, the report cited the idea of a healing environment, individualized care, autonomy of the patient in making decisions, evidence-based decision making, and the need for transparency. Although those elements of a healthcare delivery system might not seem so dramatic today, they were fairly revolutionary in 2001. This report also provided substantive support for the use of information technology within health care. In addition, it provided the impetus for payment methods being based on quality outcomes and addressed the issue of preparing the future workforce. This latter recommendation formed the basis for another IOM report, Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality (IOM, 2003). Unlike the earlier reports, the Health Professions Education report emerged as the work of an invitational summit. In this report, one of the major concerns about safety was exposed publicly, namely that we educate disciplines in silos and then expect them to function as an integrated whole. This is true of both basic and continuing professional education. The report stated, “All health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics” (IOM, 2003, p. 3). Box 2-2 emphasizes those five competencies about health professional education. After looking at safety, the system and core competencies of health professionals, the IOM turned its attention to the workplace itself. As a result, many nurses think of the IOM report Keeping Patients Safe: Transforming the Work Environment of Nurses (IOM, 2004) as the major impetus behind many changes that improved the working conditions for nurses. Because nurses are so inextricably linked with patients, it was logical that the importance of the role of nurses in health care emerged as an area of focus. This report identified that nurses had lost trust in the organizations in which they worked and that “flattening” the organization resulted in fewer clinical leaders being available to advocate for staff and patients and to provide resources to those delivering direct care. Further, numerous sources of unsafe equipment, supplies, and practices were discussed. Finally, so many organizations were still engaged in punitive practices related to errors rather than redirecting attention to the broader view of the system. Two other related reports in what is called the Chasm Series also provide guidance to nursing. These reports—Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions (IOM, 2005) and Preventing Medication Errors (IOM, 2006)—address two common encounters in healthcare organizations. Many patients who arrive at a hospital for medical or surgical intervention come with an underlying mental health or substance-use condition that complicates the basic intervention strategy. Also, medication errors are the source of many issues about patient safety. Almost all hospitalized patients and most people who have a healthcare condition and are not hospitalized use medications. The prevalence of the numbers of medications that pass hands in any organization alone would justify the work of this report. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is the primary Federal agency devoted to improving quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of health care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2008). As seen in numerous IOM reports, recommendations about what AHRQ could do to enhance safety were prominent. AHRQ’s website (www.ahrq.gov) is an information-rich source for providers and consumers alike. For example, several healthcare conditions are identified in the outcomes research section. Because AHRQ maintains current information, it is a readily available source, even if the number of conditions is limited. Another example of AHRQ’s work is the fairly well-known “Five Steps to Safer Health Care,” which is available at www.ahrq.gov/consumer/5step.htm. Nurses who work in clinics will find these steps especially helpful in working with patients. This list identifies ways in which nurses can support people in assuming a more influential role in their own care. Further, supporting people in assuming a larger role helps them receive care that is patient-centered. Box 2-3 lists the five steps.

Patient Safety

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine Reports on Quality

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

Patient Safety

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access