Violence

A Social and Family Problem

Cara J. Krulewitch*

Focus Questions

What are some of the factors that contribute to family violence?

What criteria are useful in assessing for possible abusive or neglectful situations?

Key Terms

Bullying

Child abuse

Child neglect

Child protective services

Cycle of violence

Elder abuse

Emotional abuse

Incest

Intergenerational transmission of violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV)

Mandatory reporting

Physical abuse

Sexual abuse

Social learning theory

Violence

Violence at home and in the community is an issue that generates enormous public concern and has become a focus of prevention in nursing and public health. Violence consists of nonaccidental acts that result in physical or emotional injury. Every day, local and national news reports are replete with examples of violent actions and their tragic consequences. In fact, violence has become so commonplace that it is unusual to find anyone who has not been exposed to violence either by personal experience or by acquaintance with a victim. In some communities, violence is so prevalent that residents are desensitized to it. Community members feel powerless to stop it and instead concentrate on efforts to ensure their safety and that of their family members.

Extent of the problem

Violence, like other community health problems, has patterns that, when identified, can help nurses to better understand the distribution of the problem and delineate those at risk and risk factors. What often appears or is reported as random violence is not. For example:

Care must be exercised in determining the real risks of victimization within a community based on these statistics from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2010). The myth and fear of stranger violence is often exaggerated, given that most individuals are at greater risk for victimization by family members or acquaintances.

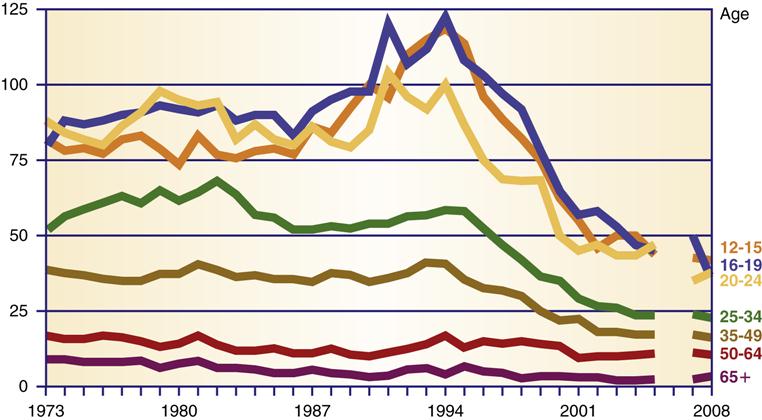

Violent and property crimes have been steadily decreasing, and in 2000, they reached the lowest levels recorded since 1973 (Rand & Truman, 2010). Adolescents and young adults are at especially high risk for being victims or perpetrators of violence, and the young from minority groups are at an exceptional risk. Figure 23-1 shows the rates of violence by age group. Teens and young adults have the highest rates of victimization, and the rates in these groups have demonstrated the most significant decline since the early 1990s. Young African American men are especially vulnerable, experiencing more overall violence than are their white male counterparts.

National health priorities to reduce violence

Violence and injury prevention is a global health priority (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010). Specific objectives in Healthy People 2020 related to injury and violence prevention are aimed at reducing injuries, disabilities, and deaths due to unintentional injuries and violence. The Healthy People 2020 box on the next page outlines the objectives related to injury and violence and progress in meeting those goals. As with many other community problems, there is a significant disparity among population groups in exposure to violence and abuse. For example, homicide is the leading cause of death in blacks aged 15 to 34 years and the second leading cause of death in black children aged 1 to 4 years (Logan et al., 2011). The homicide rate for African American men and women is well above the rate for their Hispanic and white non-Hispanic counterparts.

Violence in the community: types and risk factors

To date, there is no accurate method of predicting which individuals will engage in violent behaviors. Studies have identified factors that place individuals at greater risk for engaging in violence (Box 23-1). However, not everyone to whom these risk factors applies behaves violently. An individual’s use of violence seems to be influenced by a variety of factors both external (family, society, and other environmental conditions) and internal (innate personality characteristics).

Exposure and Social Conditioning

One explanation for violence is that people learn to use violence when violence is condoned or is considered an acceptable strategy in solving problems. This view is based on the principles of social learning theory, according to which children learn to respond with acts of violence by observing role models and seeing problem solving through violence portrayed as successful in the media (Warriner, 1994).

Many American cultural institutions model and even encourage violence and aggression. Aggressive actions are applauded in sports, movies, television, and video games. It is estimated that by the age of 18 years, the average television viewer has witnessed 200,000 acts of violence on television, in video games, and through other media channels (Committee on Public Education, 2001). This exposure to media violence is positively related to increases in aggressive behavior. Viewing violence on television, in movies, and in games has been linked to increased violence and aggression and increased risk taking in children and adolescents, which carries over into adulthood (Anderson et al., 2008; Carll, 2006; Huesmann et al., 2003). DuRant and colleagues (2006) reported that teens who watch televised professional wrestling programs are more likely to engage in fighting and date fighting, and to carry weapons. In its policy statement on media violence, the American Psychological Association (APA) calls for physicians and other health care professionals to get more involved in working with families and the political system to reduce children’s exposure to media violence (Carll, 2006). The American Academy of Pediatrics (2009) has urged parents to limit their children’s media exposure and to be actively involved in the selections of materials viewed by children and teens.

Adolescents and Violence

Adolescents are exposed to and particularly vulnerable to increasing violence at school and in the community (MacKay & Duran, 2008). An alarming number of adolescents know victims of or have witnessed assaults, rapes, or other life-threatening violence. Inner-city youth have the greatest exposure risk (Stodolska & Shinew, 2011; U.S. Department of Justice [USDJ], 2008). A cross-sectional survey of inner-city children found that 61 experienced at least one direct or witnessed victimization in the past year. Almost half had experienced a physical assault (Finkelhor et al., 2009). In 2009, 22.5% of all violent crime was committed by juveniles (Rand & Truman, 2010). Some have suggested that these family dynamics, self-concept, and self-esteem are predictive of youth violence. (Kim & Kim, 2008; Rohany et al., 2011). Bollard and colleagues (2001) found that hopelessness was relatively rare in teens; however, when present, it was predictive of fighting and carrying weapons. Other predictors of adolescent violence are poor grades, deviant behavior, weak bonds in middle school, early drug use, and association with peers using drugs (Children’s Defense Fund [CDF], 2005; RMC Research Corp, 2010). There is a high rate of co-occurrence of substance use and violence in youth (Van Dorn et al., 2009).

The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2010a; 2010b) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported the following for 2007:

Bullying

The impact of bullying and being bullied is an important aspect of violence. Bullying has health consequences across the life span. The beliefs that bullying is a normal part of growing up, that it is temporary, that its impact on health is minimal, and that it happens as a result of children’s being left unsupervised are myths and underestimate the risk and impact of bullying.

Bullying is a pattern of physical, verbal, or other behaviors directed by one or more children toward another child that are intended to inflict physical, verbal, or emotional harm. Many children with preexisting health conditions or disabilities are at risk for victimization because they are different or act differently from their peers. Children who are overweight or have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are more likely to be bullied (Cook et al., 2010; Lumeng et al., 2010).

The prevalence of bullying among middle and high school students varies widely with estimates from 7% to 54% worldwide (National Center for Education Statistics, 2007; Undheim & Sund, 2010). Male students report higher rates of bullying, and bullying is most prevalent in the sixth through eighth grades. Boys use more physical forms of bullying, whereas girls use more relational forms of bullying such as exclusion, isolation, and initiation of rumors.

Bullying is a form of violence that has a significant impact on children’s health. Many somatic and mental health complaints such as bedwetting, headaches and stomachaches, neck and shoulder pain, back pain, anxiety, fatigue, loneliness, short temper, depression, suicidal ideation, increased drug and alcohol use, aggression, and delinquency are related to being bullied (Fekkes et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; McCenna et al., 2011; Sullivan et al., 2006). Bullying is also a risk factor for violent behavior and injury and teenage pregnancy (Perren, 2011). Young people who bully or are bullied are more likely to be involved in fights, injured in fights, and carry weapons to school (Fox et al., 2003; Nansel et al., 2003). Being rejected and bullied by peers is a characteristic common to students who commit school shootings (Leary et al., 2003; Reuter-Rice, 2008).

School nurses and nurses working with children and adolescents can screen for bullying during routine health care visits such as school physicals. School nurses are more likely to see students who are bullies or have been bullied (Vernberg et al., 2011). Lyznicki and colleagues (2004) listed the following questions the nurse can ask children to help identify bullying issues:

School Violence

School violence takes many forms; for example, excessive teasing, pushing and shoving, bullying, intimidation, stalking, serious physical assault, and murder. In 2008 to 2009, students were exposed to 1.2 million nonfatal crimes at school, including 626,800 violent crimes such as assault, rape, and robbery (Robers et al., 2010). Many of these children showed signs of anxiety and depression, and 61% worried about their safety. Higher exposure to violence was associated with lower grade point average and more days absent from school. According to the U.S. Department of Education and Justice, approximately 5% of students skip school, avoid places within school, or avoid school activities because they are fearful (Robers et al., 2010). The presence of youth gangs in elementary and secondary schools increases the rate of serious crime in those schools. Approximately 20% of public schools report gang activity in their schools (Robers et al., 2010). Mulvey and colleagues (2010) described the links between gangs and drug use. This link is both at the individual level and within peer groups. When students are preoccupied with their safety and schools must divert energy and resources to deal with potential violence and violent behavior, the educational mission of the schools suffers.

Gang Violence

There were an estimated 774,000 gang members and 27,900 gangs active in the United States in 2008. This is an increase of 28% in the number of gangs and 6% in that of gang members since 2002 (Egley et al., 2010). Most gang members are male, but female membership is growing. Although most gang members are adolescents and young adults, gang members range in age from 8 to 55 years.

Gangs are flourishing in both rural and urban communities. Gangs can provide a sense of stability and family for many disenfranchised adolescents with unstable family situations (Egley et al., 2010). Gang members identify five reasons for joining gangs: (1) only option, no jobs available; (2) peer pressure; (3) protection; (4) companionship; and (5) excitement (Morrissey, 2011; Palm Bay Police Department, 2007). Having a previous conduct disorder and having friends who joined gangs or engaged in aggressive behaviors are predictive of joining a gang among adolescents (Palm Bay Police Department, 2007).

Violence is part of everyday life for gang members. Youth gang members are more likely to engage in drug use, drug trafficking, and violence than other youth and are three times more likely to be involved in violent activities than non–gang members (Morrissey, 2011; Mulvey et al., 2010; National Drug Intelligence Center, 2009). Violence is a part of their neighborhoods and families, and violence is an expected part of their role and individual status as gang members. Over half the homicides in Los Angeles and Chicago are gang related (Egley et al., 2010). In Rochester, New York, 68% of all adolescent violent offenses were committed by gang members (Howell, 2006). A sense of belonging, peer pressure, or the threat of retaliation makes it difficult for individuals to leave gangs.

Entire communities must come together to reduce gang membership and violence. Preventing young men and women from joining gangs should be the first priority. Strategies include preventing youth from dropping out of school and strengthening social institutions to better provide activities and legitimate economic opportunities for youth (CDF, 2005; USDJ, 2008). Several cities—including Boston, Massachusetts; Indianapolis, Indiana; and Stockton, California—have initiated successful comprehensive gang violence reduction programs. These entail concentrated police enforcement, involvement of community leaders and pastors in violence reduction messages, and a network of support services for at-risk youth.

Guns and Violence

Firearms are the second leading cause of death among youth aged 10 to 19 years (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [MMWR], 2011). Over a 28-year period, 110,645 children were killed by firearms. In 2007, the 3042 gun related deaths in children were almost the same as the number of U.S. deaths in Iraq (CDF, 2010). Regulations regarding the manufacture and licensing of firearms are more lenient in the United States than in other developed countries, which makes firearms easily accessible. Higher rates of household ownership and accessibility of firearms are associated with disproportionately higher homicide rates (Miller et al., 2002).

A number of interventions have been tried to reduce firearm violence in the United States. An evaluation of the laws enacted to prevent firearm violence found inconclusive evidence that bans, restrictions and waiting periods, registration and licensing regulations, laws regulating the carrying of concealed weapons, child-access laws, and zero-tolerance laws in schools and other public places have had little if any impact in reducing firearm violence (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2003). Opponents of gun control such as the National Rifle Association (NRA) argue that criminal assault and injury will continue despite gun control and that assailants will simply switch to other weapons. Proponents argue that stricter gun control laws will help to bring murder and injury rates in line with those of other nations. The National Research Council (2005) conducted a systematic literature review in 2004 and did not find significant data to support the effect of gun-control laws on reducing violence.

Additional Risk Factors

Poverty is an important risk factor associated with victimization through violence. Individuals are at greater risk for being the victims of violent acts if they are poor (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2007). Poverty and living in impoverished neighborhoods also increase the risk for IPV (Caetano and Ramisetty-Minker, 2010; CDC, 2010a; Fox & Benson, 2006). In addition, the increasing levels of drug, alcohol, and tobacco use among adolescents were associated with their increasing exposure to violence, not only in the United States but internationally (Vermeiren et al., 2003). Using drugs exposes adolescents to victimization through violence, delinquent peers, and drug dealing. Adolescents subsequently develop favorable attitudes toward violence that continue even when they are not using drugs any longer (Kuhns, 2005).

Impact of violence on the community

Violence in the community creates a sense of fear and danger. The fear of violence has a tremendous impact, causing residents to be suspicious of one another and to become more isolated. Parents’ increased concern and anxiety about safety in their neighborhoods (presence of gangs, child aggression, crime, violence, traffic) is related to lower levels of children’s physical activity and outdoor play (Stodolska & Shinew, 2011; Weir et al., 2006). The family is the first place in which acceptable social behavior is learned. Abusive behavior that starts within the family has an impact on the entire community, economically and emotionally.

Although community health nurses encounter violence and violence-related concerns in a number of situations, their most frequent professional contact is with individuals and families in clinics and homes. For this reason, the remainder of this chapter concentrates on family violence and the nursing role in prevention and intervention with the family.

Violence within the family

Family violence involves the direct use of force, emotional battering, or neglect carried out by one family member against another. It is very difficult to determine with certainty the actual prevalence of family violence. Most cases go unreported. Family violence researchers use data from both small and national samples to estimate the extent of the problem. Much of the research has also been conducted on clinical populations, those who have already been identified, and therefore, care must be taken when generalizing these findings to nonclinical populations.

Generational Patterns of Abuse

A pattern of abusive behavior in families continuing one generation after another, also called the intergenerational transmission of violence, has been widely documented. However, the relationship between being abused and witnessing abuse as a child and being abusive or victimized as an adult is complex. Not all children who grow up in violent homes become violent in later life. Lackey (2003) found that exposure to violence at home as an adolescent was strongly related to partner violence in men but not in women. Hamby and Jackson (2010) found that witnessing partner violence was closely associated with several forms of maltreatment and other forms of victimization and called for a need to better integrate services to adult and child victims of family violence. This has important leader in coordination of care.

Inequality of Family Members

Gelles and Straus (1988) contend that people abuse family members because there are few or no repercussions. There continues to be inequity in arrest or criminal prosecution for IPV. Social attitudes, the private nature of family violence, and the structural inequalities in family relationships combine to create a climate in which violence is acceptable and tolerated. Violent acts against family members often go unpunished, although similar actions against other people would be criminally prosecuted. Parental use of physical punishment is widely practiced and often socially condoned. Increased visibility of family violence and national campaigns are slowly changing public attitudes and acceptance of family violence.

What happens within the family has been considered a private “family matter.” Because of the strong belief in family privacy, neighbors, family members, and authority figures such as teachers, health care professionals, police, and prosecutors often hesitate to intervene (Jecker, 1993). Culturally, the values of men, women, and children have been considered unequal. Historically, this was supported by legal statutes under which women and children were considered property and had few rights under the law. Children could be sold into slavery, loaned to work for wages collected by the father, or bartered into marriage without legal recourse. In fact, it is still very difficult for minor children to establish rights independent of their parents. Since the late 1900s, state by state, women have slowly been granted the right to personal assets and property, independent of a spouse. It was 1929 before women in the United States were granted the right to vote nationwide. Social inequalities among family members persist, creating a climate in which violence continues.

Child abuse and neglect

The National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (2010a) reported the following for 2008:

• In the United States, 1740 died as a result of abuse or neglect.

• 1 in 5 U.S. children experience some form of maltreatment.

• Most children were maltreated by their parents, who were typically less than 39 years of age.

Children also encounter violence and abuse from caregivers other than parents. Daycare providers (especially unlicensed providers), family friends, and neighbors might also abuse children. However, the greatest risk is from family members and relatives.

Factors Associated with Abuse and Neglect

Abuse is inflicted sometimes on all of the children in a family, but often one child is singled out or targeted to receive most or all of the abusive attention. A child who is considered different or has a physical or emotional disability is at special risk of abuse (Hibbard & Desch, 2007; United Nations Children’s Fund [UNICEF], 2005). Children with disabilities are nearly 3.5 times more likely to be abused than children without disabilities (Govindshenoy & Spencer, 2007; Sullivan & Knutson, 2000). The study by Mandell and colleagues (2005) reported that 18.5% of children with autism had been physically abused. It is important to note that other siblings in the family, although spared the immediate abuse, are also affected. Removal of one child does not guarantee a solution to the problem. Another child in the household usually becomes the next target.

The nurse should exercise caution in generalizing from reported case data because these data may be biased. Although child abuse and neglect occur across the socioeconomic spectrum, poverty seems to be a risk factor, whereas parental education is a poor predictor. The rate of abusive incidents is relatively uniform across educational levels (CDF, 2005). Social expectations about race and poverty often influence who is reported as abusive.

Black children are at highest risk of substantiated maltreatment and Asian American children have the lowest risk (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2011). Children who live in homes at lower socioeconomic levels are at greater risk of substantiated maltreatment than those from higher income homes. Large national family surveys do not show African American families to be at greater risk for child abuse (Gelles & Cornell, 1990). The discrepancy between substantiated reported cases and family survey data might be explained by reporting bias. The larger number of reported cases of child abuse and neglect among the poor (more of whom are African American families) is probably the result of those families’ involvement with public social and health services and emergency departments (CDF, 2005). These caregivers are more likely to report abuse and neglect. Family cultural practices might provide supports to reduce risks for abusive situations. For example, African American and Hispanic families tend to have greater extended family involvement and use family networks for emotional, financial, and child-rearing support. These characteristics might offset the stressors of higher unemployment and less socioeconomic power.

Types of Abuse

There are four major types of maltreatment or child abuse. Generally, child abuse applies to abuse of persons younger than 18 years of age. Definitions, however, vary among the states.

Physical Abuse

Physical abuse of a child is characterized by the infliction of physical injury as a result of punching, beating, kicking, biting, burning, shaking, or otherwise harming a child. The parent or caregiver might not have intended to hurt the child; the injury might have resulted from overdisciplining or physical punishment. Box 23-2 provides examples of moderate and severe abuse as well as some injuries that might be indicative of child abuse. Because physical abuse is often not an isolated incident, evidence of past injuries might be present. The explanations for old or healing injuries should be carefully explored.

Child Neglect

Child neglect is characterized by failure to provide for the child’s basic needs (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2007). Neglect can be physical, educational, or emotional. Physical neglect includes failure to provide adequate food, clothing, and shelter; refusal to seek or delay in seeking health care; abandonment, expulsion from the home, or refusal to allow a runaway to return home; and inadequate supervision. Educational neglect includes allowing chronic truancy, failing to enroll a child of mandatory school age in school, and failing to attend to special educational needs. Emotional neglect includes such behaviors as marked inattention to the child’s needs for affection, failure to provide needed psychological care, spousal abuse in the child’s presence, and permitting drug or alcohol use by the child. Assessment of child neglect requires consideration of cultural values and standards of care as well as recognition that the failure to provide the necessities of life might be related to poverty.

Neglect is a pattern of failure to provide care rather than a single incident. In neglect cases, neighbors or relatives will frequently recall that they felt uneasy about a situation but did not report the parent or caregiver to the appropriate authorities. Substance abuse and addiction are frequently implicated in parental failure to provide an adequately nurturing environment.

Sexual Abuse

Sexual abuse includes fondling, intercourse, incest, rape, exhibitionism, and commercial exploitation through prostitution or the production of pornographic materials (USDHHS, 2007). Many experts believe that sexual abuse is the most underreported form of child maltreatment (National Center for Victims of Crime, 2011).

It is important to note that sexual abuse of children can be committed by strangers, acquaintances, or trusted leaders of the community, as well as by family members. The sex abuse scandal involving priests in the Catholic Church is a good example of how sexual abuse of children can be perpetrated by trusted members of a community and how it can stay hidden for many years. Widespread publicity and public outrage prompted changes and better oversight of priests within the Catholic Church. In approximately 80% of cases, however, the perpetrator of sexual abuse is a family member (incest), family friend, neighbor, foster parent, or guardian (USDHHS, 2007).

Emotional Abuse

Emotional abuse includes acts or omissions by parents or other caregivers that cause, or could cause, serious behavioral, cognitive, emotional, or mental disorders. Emotional or psychological abuse is very hard to detect, and the behavioral consequences might take years to develop. Acts that might not immediately harm a child can be sufficient to warrant reporting and investigation by child protective services. For example, the parents or caregivers might use extreme or bizarre forms of punishment such as confinement of a child in a dark closet. Less severe acts such as habitual scapegoating, belittling, or rejecting treatment are often difficult to prove, and therefore, child protective services might not be able to intervene without evidence of harm to the child.

Abuse and neglect are repetitive patterns of behavior. Approximately 30% of children named in reports of child abuse or neglect had been the subject of a report to child protective services at least once before in the previous 5 years (Fluke et al., 2005). In half the cases of child abuse–related deaths, a previous report of abuse or neglect had been filed with the state’s child protective agency (Child Welfare League of America, 2004). Box 23-3 reviews behaviors and symptoms common in abuse and neglect.

Impact of Child Abuse Laws

Because of national concern, the federal government enacted the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) in 1974. It was most recently amended and reauthorized on December 20, 2010. The act sets established minimum definitions of child abuse and neglect. CAPTA provides federal funding to states for use in the prevention, investigation, prosecution, and treatment of child abuse and neglect. In addition, it establishes the Office on Child Abuse and Neglect and the National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect Information.

Child abuse and neglect are crimes in all 50 states. All 50 states, plus the District of Columbia, have mandatory child abuse and neglect reporting laws that require certain professionals and institutions to report suspected cases of maltreatment to a designated child protection agency. More than 60% of all reports of alleged child abuse or neglect are made by professionals (USDHHS, 2009). These laws emerged from the moral concerns of protecting the vulnerable and promoting nurturing families (see the Ethics in Practice box). Each state has different criteria and procedures for reporting suspected cases. Child protective services is the agency assigned to investigate reports of child abuse or neglect. The emotional aspect of abuse is not clearly addressed in most laws and has been difficult to prosecute in practice. Physical neglect of a persistent nature with severe consequences is more likely to incur legal prosecution than are subtler forms of physical and emotional neglect.

To prove neglect, an adult’s recognition that his or her actions have or could cause adverse consequences to the child is usually a legal requirement to show intent. Economic, emotional, and mental health factors might cloud the issue.

Does this constitute deliberate neglect? Are there cultural or religious factors that might impact parents’ decisions to seek and follow medical care? Some of the issues the authorities would examine before deciding to prosecute include parental understanding of the risks of withholding medication, ability to pay for the prescription, and, finally, intent. Was the decision not to provide medication deliberate or the result of multiple stressors or poor coping skills?

Family Preservation Alternative

The question of what should be done with the children who are victims of child abuse is a social policy challenge. Approximately 20% of child victims are removed from their homes by court order. Most are placed in foster care (USDHHS, 2009). Many of these children will bounce between foster care and a parent before parental rights are terminated. Most will not be adopted and will remain in foster care until adulthood.

Family preservation programs are being tested as an alternative to parental punishment, jail time, or removal of children from their parents. It has been many experts’ belief that abusive families can benefit from intense, long-term community support and supervision that addresses the myriad social and family issues that precipitated the abuse or neglect. Preservation programs stress intensive intervention with all family members and stringent supervision. The intent is to provide basic needs, educate, and build on family strengths to keep families together rather than to place children in foster care. Evaluation of such programs has shown disappointing results. Some studies have found fewer subsequent reports of child maltreatment, decreased frequency of out-of-home placements of children, and use of a broader array of community support services among families linked to a family preservation caseworker who provided strong collaboration in developing a treatment plan than among families without a family preservation caseworker (CDF, 2005; Littell, 2001; Walton, 2001). Others, however, have found no improvement in the level of family functioning, effectiveness in preventing future maltreatment, or risk of future foster home placement (Chaffin et al., 2001; Walton, 1996; Westat et al., 2002).

Long-Term Consequences

Children who are abused or mistreated are at increased risk for learning disorders, mental retardation, and developmental delays, including delays in language development, speech, and gross motor activities. Abused and neglected children generally have lower IQ (intelligence quotient) scores than children with similar characteristics who have not been abused and are much more likely to have academic difficulties in school (USDHHS, 2005). Physical abuse in childhood and the cumulative effects of experiencing maltreatment and witnessing family violence are also related to chronic physical and mental health problems throughout childhood and into adulthood (DePanfilis, 2006; Turner et al., 2006).

Mistreated children find it difficult to initiate mutually satisfying interpersonal relationships with peers and adults. Their social skills and self-concept suffer. They have difficulty setting limits or boundaries with others. Classmates might describe them as socially withdrawn or as troublemakers. Physically abused individuals are more likely to be suicidal, use drugs, and exhibit aggressive behaviors (Chen et al., 2010; Currie & Widom, 2010; Rew, 2003). Children who are abused and/or neglected are at greater risk of involvement in juvenile or other criminal activity. Compared with children who are not maltreated, those who are abused and neglected are up to six times more likely to be involved in the juvenile justice system and up to three times more likely to be arrested as adults (CDF, 2005, p. 117).

Children who run away from home often do so to escape sexual and other abuse in the home (Brandford et al., 2004; National Runaway Switchboard [NRS], 2011). Girls run away more often than boys do and also run away multiple times. This suggests that girls may be subject to more dysfunctional relationships or feel less able to protect themselves at home. Once on the street, runaways are vulnerable to predators, sex traffickers, drug dealers, and those engaging in other types of exploitation (see Chapter 21). Girls and boys often engage in sex acts for money, which can lead to a lifetime of problems. Prostitution and promiscuous sexual activity are more prevalent among adults who were sexually assaulted as children. Victims of sexual abuse report lifelong difficulty in maintaining healthy adult relationships.

Intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is also often referred to as partner abuse, domestic violence, or woman battering. IPV is the leading cause of injury for women. According to national crime statistics, battering is the single most common cause of injury to women, far exceeding accidental injuries and injuries caused by other criminal activities. The rates of IPV have not decreased significantly over the past 10 years (Breiding et al., 2008). Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey (CDC, 2011a; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2000) include:

• Rates of IPV vary greatly among women of diverse ethnic backgrounds.

• Women experience more assaults and injuries from their intimate partners than men do.

There is a growing body of research documenting the range of significant health problems and resulting disability experienced by victims of physical and sexual abuse. Battered women are less healthy and have a variety of battery-related health problems. These include traumatic injuries, chronic pain, bone and joint pain, headaches, sleep disorders, autoimmune disorders, urinary and vaginal infections, unplanned pregnancy, increased substance abuse, depression, and increased suicide attempts (Bonomi et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2010; Leone et al., 2010). Adolescents who are the victims or perpetrators of severe dating violence report poorer quality of life, increased suicide ideation and attempts, substance abuse, and lower life satisfaction and risky sexual behavior (Alleyne et al., 2011; CDC, 2006; Coker et al., 2000).

Battered women use more health care services compared with women who have not been battered (Bonomi et al., 2007; Rivara et al., 2007; Ulrich et al., 2003). Battering is predictive of more hospitalizations, clinic use, and mental health service use. Rivara and colleagues (2007) estimated the total health care costs of IPV to be about $19.3 billion each year for every 100,000 women age 18 to 64 years enrolled in the health care program they evaluated.

Women are at increased risk for violence during pregnancy. Estimates vary widely, but between 8% and 65% of all pregnant women are battered. In addition to nonfatal violence, women are also at risk for fatal violence. Studies that evaluate the incidence of homicide during or up to 1 year following pregnancy estimate 8% to 46% (Krulewitch et al., 2001). In their study of women in Maryland, Krulewitch and colleagues (2003) found that female victims of homicide were twice as likely to be pregnant. Battering is also related to poor pregnancy outcomes such as miscarriage, preterm labor, and low-birth-weight infants. This suggests that both obstetric and pediatric offices might be important places to screen for IPV.

Definition

IPV entails a pattern of verbal and physical attacks by one intimate partner against the other. The definition of abuse includes violence between unmarried, cohabiting, separated or divorced, and dating partners as well. All abuse between partners, whether married, unmarried, or dating, is referred to as IPV in this chapter.

In this chapter, the assailant is referred to as male and the victim or survivor as female because in 80% of IPV incidents, the assailant is male and the victim female (Rennison, 2003). However, the size and strength differences between men and women create a perception that male-on-female violence is more frightening, which possibly draws more attention to them. There is legitimacy to the claim that cases in which the woman is the aggressor are underreported because the male victims fear ridicule (Hamby & Jackson, 2010). Whitaker and colleagues (2007) found that 25% of all relationships had some violence and that half of those were reciprocally violent. Nurses should be aware that anyone can be a victim or an assailant, so careful evaluation is critical during assessment.

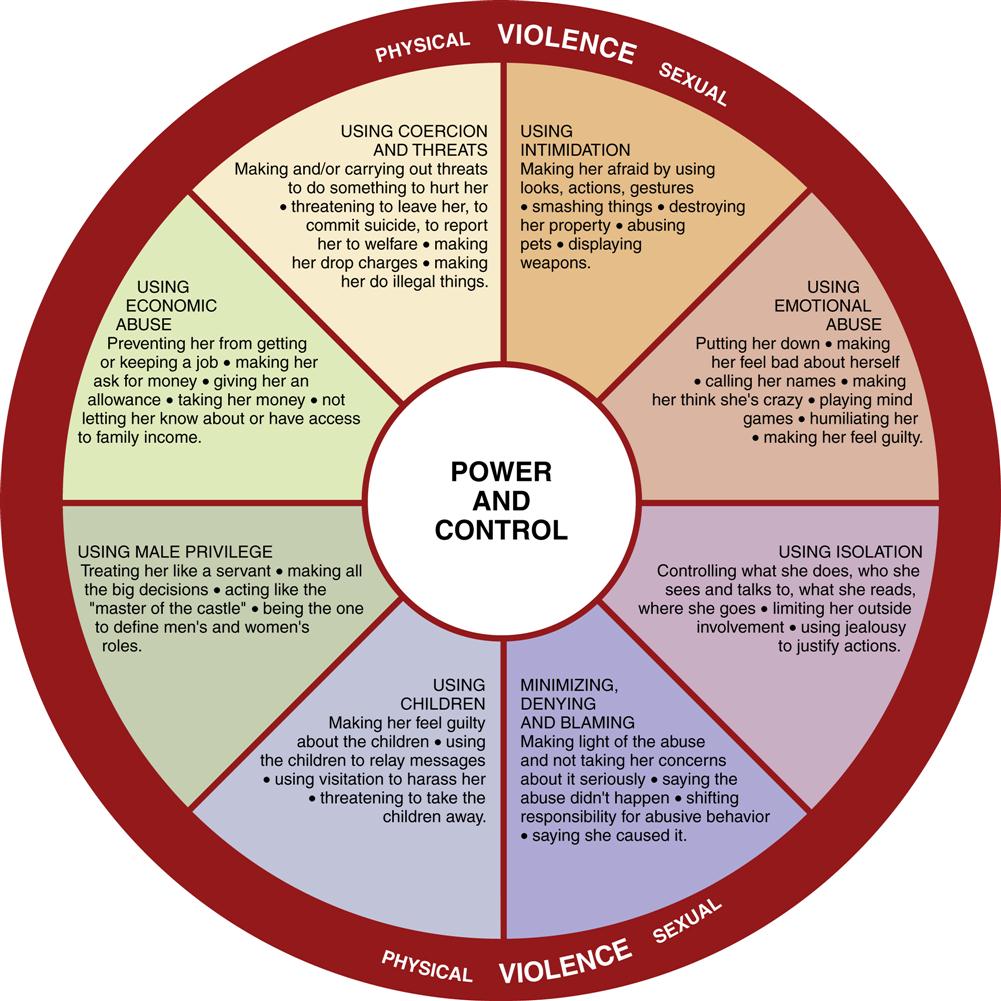

IPV includes physical, sexual, verbal, and emotional abuse. Physical assault ranges in degree from slapping to murder. Sexual abuse includes unwanted or forced sexual acts. All the abusive actions are aimed at controlling the other person, humiliating the person, and reducing the victim’s self-esteem and identity. Verbal and emotional abuse breaks down women’s self-esteem. A common theme of verbal abuse is criticism of the victim’s ability to adequately perform her roles as mother and wife. Verbal abuse convinces the victim that she deserves harsh treatment, and it serves to reinforce the abuser’s belief that his actions are justified, even required, to ensure that the spouse acts appropriately.

The Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (also called the Duluth Model) has been a pioneer in intervening to prevent men’s violence against their female partners. This treatment and education model is based on the theory that power and control are at the heart of IPV. The power and control wheel (Figure 23-2) illustrates the variety of strategies used for controlling others’ behaviors. These behaviors should serve as warning signs of potentially abusive relationships.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree