Disaster Management

Caring for Communities in an Emergency

Christina Hughes and Frances A. Maurer*

Focus Questions

What are the different types of disasters?

What happens when a disaster occurs? Who is in charge?

What are the common physical and psychosocial effects on disaster victims and workers?

What are the agencies that might be involved in predisaster planning?

What impact has terrorism had on disaster planning efforts?

What are the responsibilities of community/public health nurses in disaster nursing?

What is your emergency preparedness plan? Your family’s plan?

Key Terms

Biological terrorism (bioterrorism)

Chemical terrorism

Disaster

Disaster nursing

Man-made disasters

Mass casualty incident

Multiple casualty incident

Mitigation

Natural disasters

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

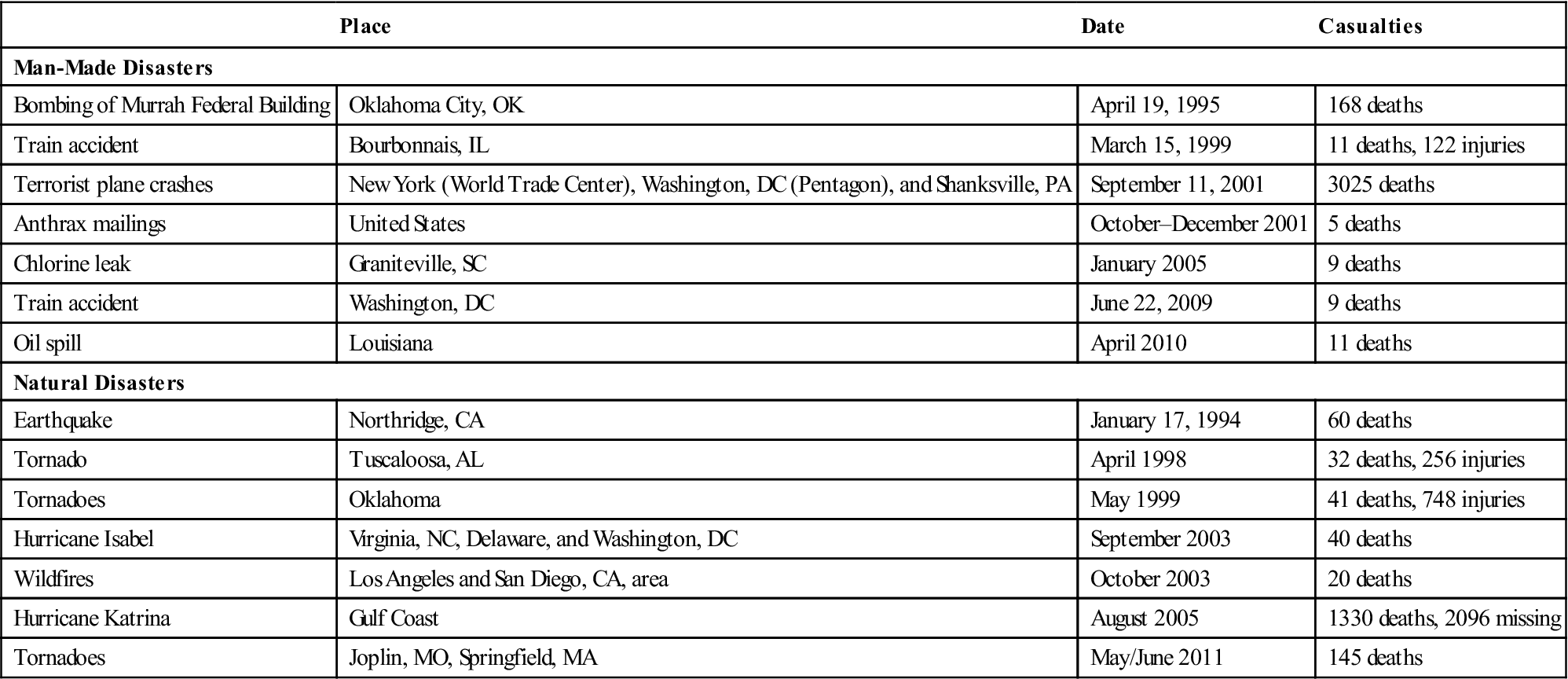

Disaster occurs in many forms: floods, wind, fire, explosions, extreme range of environmental temperatures, epidemics, multiple car crashes with many casualties, school shootings, and environmental contamination from chemical agents and/or bioterrorism. The Louisiana Gulf Oil Spill of 2010 and the resulting environmental damage is one example of disaster. In the past 10 years, many natural and man-made disasters have occurred in the United States (Table 22-1). Flooding is the most common natural disaster worldwide and is the third leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration [NOAA], 2011). Major floods in the Northwest, the Midwest, North Dakota, and the Southeast cost billions of dollars in lost homes, businesses, and crops and created long-term shelter needs for thousands of people. The Japanese tsunami of 2011 caused an estimated $309 billion in damages to personal property and public infrastructure (Voice of America [VOA] News, 2011).

Table 22-1

Examples of Disasters—United States

| Place | Date | Casualties | |

| Man-Made Disasters | |||

| Bombing of Murrah Federal Building | Oklahoma City, OK | April 19, 1995 | 168 deaths |

| Train accident | Bourbonnais, IL | March 15, 1999 | 11 deaths, 122 injuries |

| Terrorist plane crashes | New York (World Trade Center), Washington, DC (Pentagon), and Shanksville, PA | September 11, 2001 | 3025 deaths |

| Anthrax mailings | United States | October–December 2001 | 5 deaths |

| Chlorine leak | Graniteville, SC | January 2005 | 9 deaths |

| Train accident | Washington, DC | June 22, 2009 | 9 deaths |

| Oil spill | Louisiana | April 2010 | 11 deaths |

| Natural Disasters | |||

| Earthquake | Northridge, CA | January 17, 1994 | 60 deaths |

| Tornado | Tuscaloosa, AL | April 1998 | 32 deaths, 256 injuries |

| Tornadoes | Oklahoma | May 1999 | 41 deaths, 748 injuries |

| Hurricane Isabel | Virginia, NC, Delaware, and Washington, DC | September 2003 | 40 deaths |

| Wildfires | Los Angeles and San Diego, CA, area | October 2003 | 20 deaths |

| Hurricane Katrina | Gulf Coast | August 2005 | 1330 deaths, 2096 missing |

| Tornadoes | Joplin, MO, Springfield, MA | May/June 2011 | 145 deaths |

Frequently occurring natural and man-made disasters during the past 30 years have brought the need for emergency preparedness to the attention of the American public. Hurricanes, earthquakes, brush and forest fires, and terrorism have created a concern across the country for preparedness. In the 1990s and in 2001, Americans experienced terrorist acts that pointed to an urgent need for special planning, training, and organization to treat mass casualties and address the threat of chemical and biological terrorism. These threats require more coordinated disaster planning and response from a broader team of emergency responders and agencies.

Worldwide, there has been an increase in terrorist activities. In 2005, terrorists bombed the London transit system, killing 56 people and injuring another 700. In the United States, bombings of public buildings have targeted abortion clinics, the World Trade Center in New York City, a federal building in Oklahoma City, and Olympic Park in Atlanta during the 1996 Summer Olympics. Almost 11,000 incidents of terrorism occurred worldwide in 2009, most in South Asia. These incidents claimed over 58,000 lives (U.S. Department of State, 2010). In the United States, the most egregious example of a man-made disaster was the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which caused mass casualties and major property damage in New York City and at the Pentagon in Washington, DC. These attacks were followed by a bioterrorist act involving the mailing of anthrax-contaminated letters to locations on the East Coast.

Successful efforts to address these and other disaster situations demand sophisticated preplanning measures and a well-coordinated emergency response during the actual disaster situation. Comprehensive planning requires the combined efforts of all levels of government, academia, health care professionals, business, and voluntary organizations cooperating to develop contingency plans to meet situations that might arise during and after the occurrence of the actual disaster.

Definition of disaster

The American Red Cross (ARC) defines a disaster as “a threatening or occurring event,” either natural or man-made, “that causes human suffering and creates human needs that victims cannot alleviate without assistance” (ARC, 2008). The Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act (Public Law 93-288) defines a major disaster as “any natural catastrophe (including any hurricane, tornado, storm, high water, wind-driven water, tidal wave, tsunami, earthquake, volcanic eruption, landslide, mudslide, snowstorm, or drought), or, regardless of cause, any fire, flood, or explosion, in any part of the United States which in the determination of the President causes damage of sufficient severity and magnitude to warrant major disaster assistance under this Act to supplement the efforts and available resources of States, local governments, and disaster relief organizations in alleviating the damages, loss, hardship, or suffering caused thereby” (Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], 2007, p. 2). There have been more than 1998 presidential disaster declarations since 1953. Website Resource 22A ![]() provides a map showing the types and distributions of these disasters.

provides a map showing the types and distributions of these disasters.

A major disaster can create a mass casualty incident or a multiple casualty incident. A multiple casualty incident is one in which more than 2 but fewer than 100 persons are injured. Multiple casualties generally strain and, in some situations, might overwhelm the available emergency medical services (EMS) and resources. A mass casualty incident is a situation in which there are a large number of casualties, usually 100 or more, that significantly overwhelm the available EMS, facilities, and resources.

When there are mass casualties, a community or region usually requires the assistance of emergency personnel and resources from surrounding communities or states. The September 11, 2001, plane crashes in Manhattan; Washington, DC; and Pennsylvania and the 2011 earthquake in Haiti are examples of mass casualty incidents in which the affected communities required outside assistance.

Types of Disasters

Essentially, there are two types of disasters: natural and man-made. Both types vary in intensity, severity, and impact. Natural disasters include hurricanes, tornadoes, flash floods, blizzards, slow-rising floods, typhoons, earthquakes, avalanches, epidemics, and volcanic eruptions. Man-made disasters include war, chemical and biological terrorism, transportation accidents, food or water contamination, and building collapse. Fire can be either man made or naturally occurring. Both the California fires of 2003 and the New Mexico fire of 2011 resulted from a combination of man-made and natural causes: arson/accident and weather conditions (i.e., a dry summer season and high winds). The New Mexico fire was started by a tree collapsing on a power line and burned almost 120,000 acres (KKTV, 2011).

Agents of Harm or Damage in a Disaster

The agent is the physical entity that actually causes the injury or destruction. Primary agents include falling buildings, heat, wind, rising water, chemical and biological agents, and smoke. Secondary agents include bacteria and viruses that produce contamination or infection after the primary agent has caused injury or destruction.

Primary and secondary agents vary according to the type of disaster. For example, a hurricane with rising water can cause flooding and high winds; these are primary agents. Secondary agents include damaged buildings and bacteria or viruses that thrive as a result of the disaster. In an epidemic, the bacteria or virus causing a disease is the primary agent rather than the secondary agent.

Factors affecting the scope and severity of disasters

A number of factors affect the degree of impact that disasters will have on individuals, families, and communities. These factors are addressed in the following section.

Vulnerability of a Population or Individual

Certain characteristics of humans influence the severity of the disaster’s effect on individuals and communities. For example, the age of a person, preexisting health problems, degree of mobility, and emotional stability all play a part in how someone responds in a disaster situation. Those most severely affected by a disaster are the physically handicapped who have limited mobility or are wheelchair dependent; people who are ventilator dependent or attached to other life-support equipment; the mentally challenged; older persons, who might have trouble leaving the area quickly; young children whose immune systems are not fully developed; and persons with respiratory or cardiac problems. For example, a fire in a nursing home, a more vulnerable community, is potentially more lethal than a fire in a college dormitory. Nursing home residents are at greater risk because they are less physically fit and more susceptible to the consequences of smoke inhalation and other consequences than are young college students.

Environmental Factors and Type of Impact

In a disaster situation, physical, chemical, biological, and social factors influence the scope and severity of the outcomes. Physical factors include the time when the disaster occurs, weather conditions, the availability of food and water, and the functioning of utilities such as electricity and telephone services. For example as a result of Hurricane Katrina in 2005, residents of New Orleans were without drinking water due to broken water mains and approximately three million homes or facilities were without power (NOAA, 2005). Some communities were without power for a short period (1 to 2 days), whereas others were without power for weeks or months. In general, those without electricity for longer periods have a more difficult time coping with the disaster than those who are without power for a day or so. In Japan, the Tokyo Power Company initiated rolling blackouts (3–6 hours) on a rotating basis to avoid a complete power shut down in the affected areas (National, 2011).

Chemical, biological, and social factors impact the scope and severity of a disaster. Leaks of stored chemicals into the air, soil, groundwater, or food supplies are examples of chemical factors. Biological factors are those that occur or increase as a result of water contamination, improper waste disposal, insect or rodent proliferation, improper food storage, or lack of refrigeration owing to interrupted electricity service. Some social factors to consider are those related to an individual’s support systems. Loss of family members, changes in roles, and the questioning of religious beliefs are social factors to be examined after a disaster. In general, individuals and families with ample social support do better in coping with emergencies than do individuals with little or no social support.

Warning Time and Proximity to Disaster

Demi and Miles (1983) identified both situational and personal factors that influence an individual’s response to a disaster. Situational variables include the amount of warning time before disaster occurs, the nature and severity of the disaster, physical proximity to the disaster, and the availability of emergency response systems. An individual’s reaction to a disaster will be greater if there is little or no warning and the victim is in physical proximity to the disaster site. For example, the loss of life in tornadoes is often affected by warning systems. When towns have warning sirens and a planned system of monitoring for potential tornadoes, more people are able to take shelter. In these instances, even with substantial damage to buildings and personal property, personal injuries and deaths are limited.

The closer an individual is to the actual site of the disaster and the longer the individual is exposed to the immediate site of the disaster, the greater the psychological distress that the individual experiences. A research study of residents in Manhattan conducted 5 to 8 weeks after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks found a high risk for depression and posttraumatic stress disorder in this population (Galea et al., 2002).

Individual Perception and Response

Personal variables influence an individual’s reaction to a disaster. Psychological proximity, coping ability, personal losses, role overload, and previous disaster experience all influence individual response. An individual’s risk for developing severe psychological consequences is greater if that person is emotionally close to the individuals affected, has compromised coping abilities, has experienced many losses, feels overloaded in her or his role, or has never before experienced a disaster. Psychological reactions in the aftermath of disasters are addressed in greater detail later in this chapter.

An individual who perceives a disaster to be less severe than it is will probably have a less severe psychological reaction than a person who perceives the situation as catastrophic (Richtsmeir & Miller, 1985). An individual’s perception of an emergency or disaster might evolve over time as the person begins to acknowledge the full impact of the disaster. The human mind is capable of allowing perceptions to be only as disastrous as the mind can cope with at a given time.

Dimensions of a disaster

Disasters can differ along a number of dimensions: predictability, frequency, controllability, time, and scope or intensity. These dimensions influence the nature and possibility of preparation planning as well as the response to the actual event.

Predictability

Some events are more easily predicted than others. Advances in meteorology, for example, have made it more feasible to accurately predict the probability of certain types of natural, weather-related disasters (e.g., tornadoes, floods, and hurricanes), whereas other disasters such as earthquakes are not as easily predicted. Man-made disasters such as explosions or vehicle crashes are also less predictable. Authorities and emergency personnel have more time to prepare for the situation when an event is predictable than when an event is not foreseeable.

Frequency

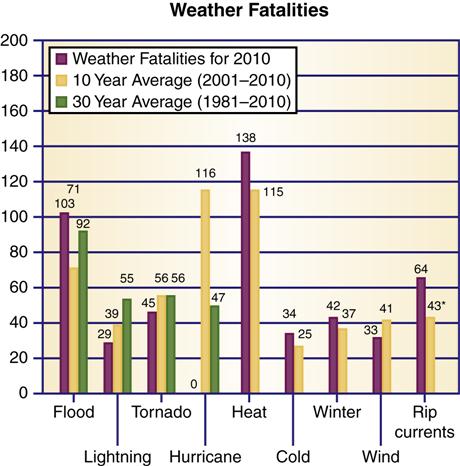

Although natural disasters are infrequent, they appear more often in certain geographical locations. Residents of the Gulf Coast of the United States live in what is commonly referred to as “hurricane alley.” These people are at greater risk for experiencing a hurricane than someone who lives in Alaska. California residents are at greater risk for earthquakes, and people who live near large river systems are at greater risk for flooding than people who live elsewhere. The National Weather Service calculates that average annual fatalities for hurricanes and tornados have increased (Figure 22-1). Most deaths are from heat-related causes, which were not calculated until recently. However, the greater frequency and intensity of natural disasters may or may not prepare citizens for their occurrence. Some citizens become immune to repeated warnings and are less likely to seek shelter to protect themselves and their property when warned. Other citizens take each warning seriously and regularly take appropriate safety precautions.

Controllability

Some situations allow prewarning and control measures that can reduce the impact of the disaster; others do not. Mitigation is a term used in disaster planning that describes actions and/or processes that can be used to prevent or reduce the damage caused by a specific disaster event. In the Midwest floods of 2011, for example, some control and mitigating actions were possible. Emergency planners were able to control some of the effects of the flooding by sandbagging levees and riverbanks to reduce the effects of water damage and by deliberately blasting dikes and dams to divert flood waters to less populated areas. The immediate impact on people was reduced by the ability of emergency personnel to organize evacuations and decrease the risk of injury and death. Sometimes the scope of a disaster can overwhelm resources available to mitigate the effects (Figure 22-2). After Hurricane Katrina, many citizens of New Orleans who were poor and disabled were stranded because there were inadequate resources to aid with evacuation. The Gulf Oil Spill leaked over 205 million gallons of crude oil, which has resulted in a long-term cleanup effort.

Many oil soaked birds and dolphins were found in the aftermath of the Louisiana Gulf Oil Spill. (A, From Federal Emergency Management Agency, Washington, DC. Retrieved July 7, 2011 from http://www.photolibrary.fema.gov/photolibrary/photo_details.do?id=19208; B, From U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC. Retrieved July 9, 2011 from http://digitalmedia.fws.gov/cdm4/item_viewer.php?CICOROOT=/natdiglib&CISOPTR=10504&CISOBOX=1&REC=9.)

The Los Angeles earthquake of 1994 did not allow prewarning and immediate precautionary actions, but other types of control measures were available. Mitigating measures can be implemented well in advance of potential disasters. The enactment of building standards and codes intended to reduce the harmful effects of a disaster are one example. More stringent fire safety measures (e.g., smoke detectors, sprinkler systems, improved fire doors) have made more newly constructed buildings safer in the event of an actual fire. Newer buildings that complied with more stringent construction codes survived the most recent San Francisco earthquake with less structural damage than did older buildings built before these codes were implemented. Los Angeles was in the process of retrofitting its freeway system to strengthen highway resistance to earthquake damage when the last big earthquake hit the area in 1994.

Time

Time factors that relate to disaster impact include the speed of onset of the disaster, the time available for warning the population, and the actual length of time of the impact phase. It is more difficult to prepare for very sudden events. A flash flood, for instance, might catch many unaware, whereas gradual flooding allows more time for preparation. When there is a lengthy period of warning, more protective measures can be introduced. For example, several days’ warning allows authorities in low coastal areas to evacuate vulnerable communities before a hurricane hits. Tornadoes do not offer such lengthy warning periods. The impact phase of the disaster might last for minutes, hours, or even days. The most damage is generally caused by the worst possible combination of time factors: a rapid onset, no opportunity for warning the populace, and a lengthy duration of the impact phase.

Scope and Intensity

Scope refers to the geographical area and social space dimension impacted by the disaster agent. A disaster might be concentrated in a very small area or involve a very large geographical region. A disastrous event might affect a small segment or a large percentage of the population in a geographical area. Intensity refers to a disaster agent’s ability to inflict damage and injury. A disaster can be very intense and highly destructive, causing many injuries and deaths and much property damage, or be less intense, with relatively little damage done to property or individuals.

Scope and intensity should be considered separately in disaster planning. For example, in the case of a building explosion, the scope is small, with a limited area of a community affected, but the intensity is great. The explosive forces are highly destructive to the building and cause death and injury to people within the building and in the immediate vicinity. A tornado is another example of a high-intensity and small-scope disaster; in contrast, a hurricane can have a high intensity and a large scope of impact. The area of damage from a specific hurricane can cover several states and involve many communities. An explosion at a water-purifying plant might cause minimal injury to property and personnel at the plant but might reduce or eliminate the water supply for an entire community for days or even weeks.

Phases of a disaster

There are three phases to any disaster: preimpact, impact, and postimpact phases. The actions of emergency personnel and other health care professionals depend on which phase of the disaster is at hand.

Preimpact Phase

The preimpact phase is the phase before a disaster. This is the time for disaster planning and mitigation before the actual occurrence. Disaster planning activities have a critical influence on how a disaster will affect a region, state, and community. This is the time for assessment of probabilities and risks of occurrence of certain types of disasters. Based on risk assessment and hazard vulnerability analyses, specific action plans should be designed to reduce the effects of predicted disasters. Mitigation might involve legislating specific building codes and land-use restrictions. Assessment and inventory of resources for special equipment, supplies, and personnel necessary to support an emergency response is essential. Planning activities should be coordinated by the emergency management agency and should involve all appropriate governmental agencies, public safety organizations, private organizations, and health care entities. Disaster plans and personnel training must be reviewed and tested on a regular basis. A critical component of the predisaster phase preparation is education of the public to encourage individual preparedness. Examples of public education are the hurricane watch preparation and evacuation procedures for communities in the Southeast hurricane belt.

An important part of the preimpact phase is the warning opportunity. A warning is given to a community at the first possible sign of danger. For some disasters, no warning is possible. However, with the aid of weather networks, satellites, and new weather-monitoring technology, many meteorological disasters can be predicted.

Giving the earliest possible warning is crucial to preventing loss of life and minimizing damage. This is the period when the emergency operations plan is put into effect. Emergency operations centers (EOCs) are opened by the state or local emergency management agency. Communication is a key factor during this phase. Disaster personnel will call on amateur radios, radio and television stations, and any other available sources to alert the community and keep citizens informed. The community must be educated to heed warnings and to recognize threats as serious. When communities experience several false alarms, members may not take future warnings very seriously.

The role of the nurse during the warning period will vary depending on her or his employer’s role in disaster response. Nurses should be informed of their specific roles and responsibilities for disaster response. Community health nurses might be assigned to assist the ARC in preparing shelters, to assist with emergency aid stations, and to establish contact with other emergency service groups.

Nurses should establish their own family disaster response plans to protect their families and homes while still being able to respond to their communities’ need. The nurse’s personal plan should address options for emergency communication with family members and employer as well as child care, pet care, and transportation options.

Impact Phase

The impact phase occurs when the disaster actually happens. It is a time of enduring hardship or injury and of trying to survive. This is a time when individuals help neighbors and families at the scene, a time of holding on until outside help arrives. The impact phase might last for several minutes (e.g., during an earthquake, plane crash, or explosion) or for hours, days, or weeks (e.g., in a flood, famine, or epidemic).

During this phase, there should be a preliminary assessment of the nature, extent, and geographical area of the disaster. The number of persons requiring shelter, the type and number of anticipated disaster health care services, and the general health status and needs of the community must be determined. It is important to have an estimate of the needed emergency resources as soon as possible after a disaster event to activate mutual aid plans and ensure a timely response from emergency medical services and other vital community support services.

The impact phase continues until the threat of further destruction has passed and the emergency plan is in effect. If there has been no warning, this is the time when the EOC is established and put in operation. The structure and functions of the EOC are addressed in more detail later in this chapter. The ARC oversees the opening of shelters in many communities. Every shelter has a nurse as a member of the ARC disaster action team. The nurse is responsible for assessing health needs and providing physical and psychological support to victims in the shelters. During the impact phase, injured persons undergo triage, morgue facilities are established and coordinated, and search and rescue activities are organized.

Postimpact Phase

The postimpact phase has two components: emergency and recovery. The emergency phase begins at the end of the impact phase and ends when there is no longer any immediate threat of injury or destruction. The emergency phase is the time of rescue and first aid. Incident command is established if it was not established in the warning phase. An assessment is made to establish the extent and types of emergency resources needed.

Recovery begins during the emergency phase and ends with the return of normal community order and functioning. The disaster planning cycle should begin again during the recovery phase. Evaluation of the current disaster plan and community response should be done based on the recent disaster. Debriefing should occur for all disaster response agencies and personnel. The disaster plans should be modified in keeping with the lessons learned from the most recent event. For survivors of a disaster, the impact phase might last a lifetime (e.g., victims of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks).

Effects of Disaster on the Community

Not only are individuals affected physically and emotionally by a disaster, but the entire community is also affected. Local and regional economies can be devastated by a disaster and require years of recovery. By 2006, the federal government had committed over $110 billion, and citizens had donated almost $3.5 billion in cash and in-kind services to ongoing Gulf Coast rebuilding efforts (White House, 2006). The most important disruptions to the community are the following:

• Public service personnel are overworked.

• Resources such as food and medical supplies are depleted.

• Rumors run rampant and are hard to check.

In a disaster, the social and psychological reactions of individuals are closely interwoven with those of the community. Usually, there are four phases of a community’s reaction to a disaster:

Disaster management: responsibilities of agencies and organizations

Governments bear the primary responsibility for designing and implementing disaster relief. All planning begins at the local level. Private and voluntary agencies contribute expertise and efforts to selected areas as designated by government plans. The key to effective disaster management is predisaster planning and preparation.

Planning

The purpose of disaster planning is to provide the policies, procedures, and guidelines necessary to protect lives, limit injury, and protect property immediately before, during, and after a disaster event. A comprehensive emergency management plan addresses four areas: (1) mitigation, (2) preparedness, (3) response, and (4) recovery.

A comprehensive plan demands a coordinated, cooperative effort among many different people, agencies, and levels of government. Planning should use valid assumptions about possible disaster agents based on previous community, state, and regional experiences, as well as experiences from other regions. The United Nations (UN) General Assembly has identified disaster events as a major threat to the global community and declared the 1990s as the International Decade of Natural Disaster Reduction. The UN called for a worldwide planning effort to reduce loss of life and property. As part of the UN effort, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a planning guide for community emergency preparedness to assists countries in preplanning efforts, personnel training, and post disaster recovery (WHO, 2010).

Planning requires technology to forecast events; engineering to reduce risks; public education about potential hazards; surveillance systems to detect environmental hazards; a coordinated emergency response; and a systematic assessment of the effects of a disaster to better prepare for future disasters. Responsibility for addressing these five areas of disaster planning is shared by federal, state, local, and voluntary agencies. Some of the organizations involved in disaster planning and relief are listed in Community Resources for Practice at the end of this chapter.

Federal Government

The federal government generally enacts laws and provides funds to support state and local governments. The Public Disaster Act of 1974 (Public Law 93-288) provided for consolidation of federal disaster relief activities and funding under a single agency.

Federal Emergency Management Agency

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) was established in 1979 as the coordinating agency for all available federal disaster assistance. The agency works closely with state and local governments by funding emergency programs and providing technical guidance and training. The scope and intensity of FEMA’s response to a disaster is influenced by the severity of the disaster’s impact on the community. If damage is limited and the existing local, state, and regional resources can handle the problems, FEMA’s services might not be needed. FEMA responds to all moderate (level II) and massive (level I) disasters. FEMA provides both direct aid (supplies and personnel) and indirect services (funding and coordination efforts). FEMA oversees long-term recovery efforts as those still underway in the Gulf states. In 2003 FEMA was consolidated into the Department of Homeland Security (DHS).

FEMA manages and helps develop local metropolitan medical response systems (MMRS). That system contracts with emergency management of existing emergency response systems, medical and mental health care providers, public health departments, law enforcement agencies, fire departments, EMS, and the National Guard (local MMRS) to provide an integrated, unified response to a mass casualty event.

Department of Homeland Security

The President created the DHS as a response to the terrorist attacks in 2001. A Presidential Directive (HSPD-5) in 2003 ordered the creation of a National Response Plan (NRP). The NRP was periodically updated to incorporate lessons learned from exercises and real-world events. In 2008, the NRP was superseded by the National Response Framework (NRF). The NRF establishes a comprehensive, national, all-hazards approach to domestic incidence response. The Framework identifies the key response principles, as well as the roles and structures that organize a coordinated and effective national response by communities, states, the federal government, and private-sector and nongovernmental partners. In addition, it describes special circumstances in which the federal government exercises a larger role, including incidents in which federal interests are involved and catastrophic incidents in which a state would require significant support. An important element of the NRF is the National Incident Management System (NIMS), a consistent nationwide system that standardizes incident management practices and procedures. Under the NRF, the DHS is responsible for mass care; that is, the coordination of nonmedical services such as shelter, food, emergency first aid, search and rescue, and efforts to reunite displaced family members (USDHS, 2011).

Department of Health and Human Services

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) partners with the Departments of Agriculture, Defense, Energy, Justice, and Transportation; the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA); the DHS; the National Communications System; and the U.S. Postal Service and serves as the lead federal agency for public health and medical services under the NRF. The USDHHS also directs and manages the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS). The NDMS is designed to deal with medical care needs in disasters of great intensity and scope that overwhelm the local health care system (USDHHS, 2010). It has three main objectives:

Other agencies supporting the NDMS include the DHS and the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Department of Health and Human Services

The emphasis in disaster planning at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is prevention and/or mitigation of epidemics and biochemical hazards (both natural and deliberate terror). The CDC has updated and refined its surveillance system to rapidly identify health threats to the population. Educating health care professionals to recognize and treat biochemical hazards is a priority (CDC, 2011). There is a concern that biological agents, such as those causing smallpox, anthrax, and influenza, can be used as weapons. The CDC has developed recommendations for preevent smallpox vaccinations and plans for mass immunization of health care workers and other emergency personnel if the need arises (CDC, 2003a). In 2003, the CDC mailed an informational packet about smallpox to all health care providers and encouraged health care professionals to register online to receive updated information (CDC, 2003b). Other CDC activities are addressed later in the chapter.

The federal government has other agencies involved in disaster relief. Website Resource 22B ![]() lists most agencies and their responsibilities during disaster. A few examples are mentioned here. The National Guard provides transportation, assistance with evacuations, and police services when local or area police resources are strained or overwhelmed by disaster needs. The temporary housing program of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development helps families either relocate or repair their homes. The EPA coordinates oil and hazardous materials removal and mitigation. The FEMA oversees long-term community recovery.

lists most agencies and their responsibilities during disaster. A few examples are mentioned here. The National Guard provides transportation, assistance with evacuations, and police services when local or area police resources are strained or overwhelmed by disaster needs. The temporary housing program of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development helps families either relocate or repair their homes. The EPA coordinates oil and hazardous materials removal and mitigation. The FEMA oversees long-term community recovery.

State Governments

State governments coordinate the development of the state emergency operations plan and establish an emergency management agency to coordinate the state response to a disaster event. For disaster planning purposes, if the disaster involves more than one local jurisdiction, the state might coordinate response services.

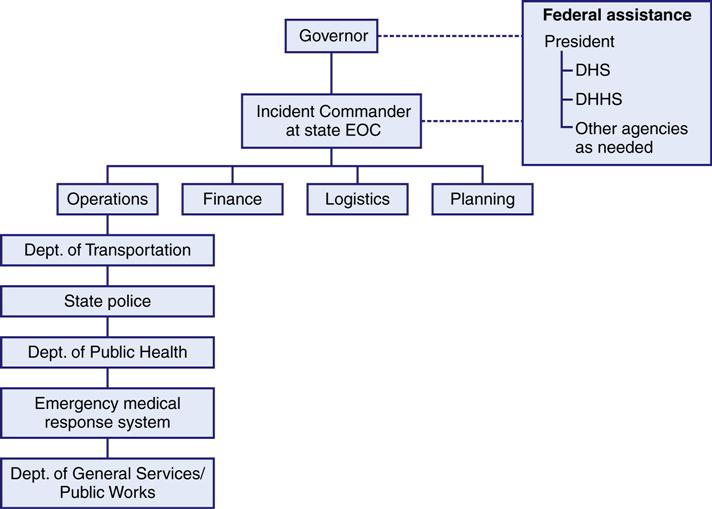

Usually, there is one state agency designated as the emergency management agency for all state-coordinated disaster efforts. When a disaster happens, the state governor will open the state’s EOC, in which some state agencies (e.g., state police; National Guard; state emergency medical services; and state health, welfare, and social service agencies) will work together at the same location to direct their specific agency’s functions for disaster relief (Figure 22-3). Most states also have a state coordinator to manage fire department resources and personnel.

The state emergency management agency advises the governor when the state has exhausted its resources or the disaster is predicted to be of such magnitude that the state does not have the resources to respond and manage the disaster event. The governor then notifies the FEMA that federal disaster relief assistance is needed. Timely assessment and evaluation of the local and state resources and their ability to respond to any disaster event is critical to activate the appropriate communication channels to obtain federal assistance and mutual aid from surrounding states in a timely manner during a disaster event.

Local Governments, Communities, and Volunteer Groups

Local governments are responsible for the safety and welfare of their citizens. They act to protect the lives, health, and property of their citizens; carry out evacuation rescues; and maintain public works. Local disaster response organizations should include local area governmental agencies such as fire departments, police departments, public health departments, public works departments, emergency services, and the local branch of the ARC.

Communities must have an emergency operations plan. Local planning efforts include contingency action plans for various types of disaster situations, designation of an overall incident commander, and identification of community resources that can be used in a disaster. The plan is developed and tested in mock-disaster exercises and then revised and refined. The local emergency management agency has communication links with the state’s EOC and with the FEMA and the DHS.

Area hospitals develop their own action plans for handling small community disasters such as a school bus accident or a large apartment fire. They are also involved in community planning preparation for larger-scale disasters that require a coordinated community effort. Local hospitals play an important role in the NRF. Local volunteer organizations such as the Boy Scouts, Girl Scouts, Jaycees, veterans associations, community emergency response teams, and church groups, can be considered additional resources to be used as the need arises. Local health care professionals who do not participate in community organizations that are officially involved in disaster planning might be called on to volunteer their services during an emergency.

American Red Cross

The ARC was founded in 1881 by Clara Barton. It is a voluntary agency that was granted a charter on January 5, 1905, by the U.S. Congress. The charter gives the ARC the authority to act as the primary voluntary national disaster relief agency for the American people and to be ready for immediate action in every part of the United States. The federal statute allows the ARC to coordinate efforts with other federal agencies. This federal legislation applies only to those emergencies and major disasters that have been declared as such by the President. On a national level and in many communities, the ARC acts to coordinate the disaster relief efforts of a variety of voluntary agencies. The ARC has created five programs to meet the human needs of a disaster (Box 22-1).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree