Gail L. Heiss*

Health Promotion and Risk Reduction in the Community

Focus Questions

What is the difference between promoting health and preventing illness?

What models help explain health-related behaviors?

What influences the health of a society?

What are the major national policies for health promotion?

Key Terms

Clinical practice guidelines

Environmental restructuring

Faith community nursing

Health-belief model

Health-promoting behaviors

Health promotion

Health-promotion model

Health-protecting behaviors

Health-risk appraisal

Information dissemination

Lifestyle assessments

Lifestyle modification

Parish nursing

Primary health care model

Risk reduction

Self-efficacy

Social support

Transtheoretical model of behavioral change

Wellness

Health information assaults our senses daily. Advertisements and articles about healthy living, healthy diets, health clubs, new vitamins, new medications, and new exercise programs are on the television, the radio, the Internet, magazine racks, and social media sources such as Facebook and Twitter. Americans are trying and buying and moving toward health—or are they? A review of the recently launched Healthy People 2020 objectives will provide perspective on three decades of benchmarks and monitored progress related to the nation’s health, the impact of prevention activities, and the movement toward health for all. Healthy People 2020 is an interactive website that replaces the previously published print version as the main vehicle for dissemination of this important information (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010, http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020).

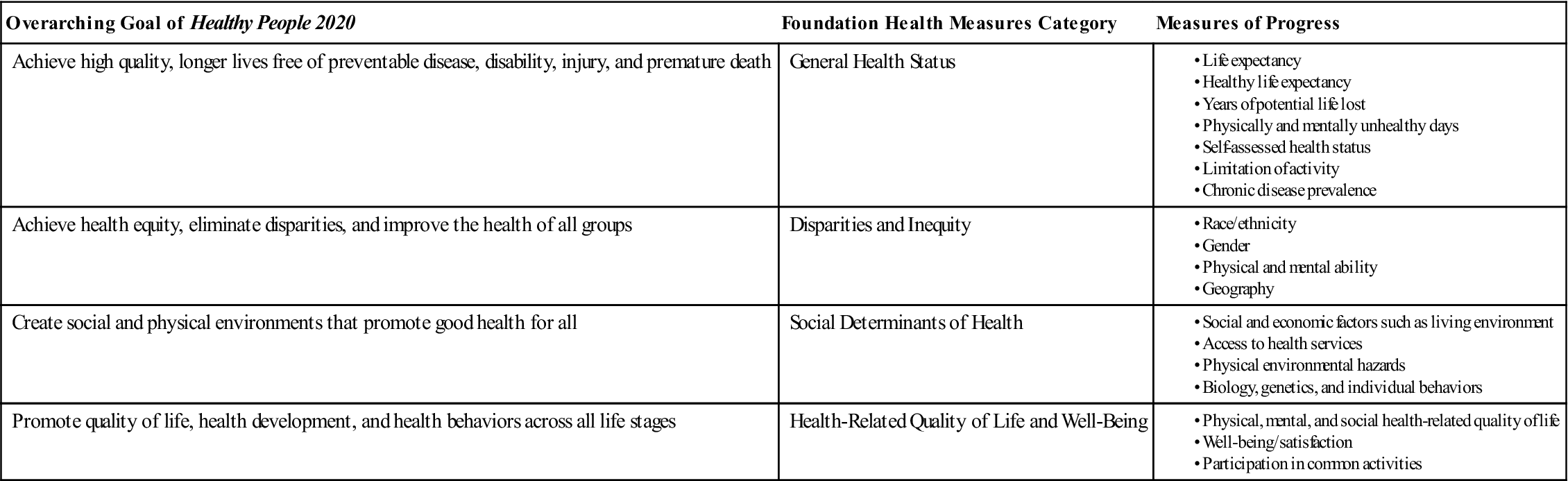

Healthy People 2020 is the most current plan to improve the nation’s health and is designed to achieve four overarching goals: (1) Achieve high quality, longer lives free of preventable disease, disability, injury, and premature death, (2) Achieve health equity, eliminate disparities, and improve the health of all groups, (3) Create social and physical environments that promote good health for all, and (4) Promote quality of life, health development, and health behaviors across all life stages. The Healthy People 2020 plan includes 42 topic areas that contribute to the achievement of these four overarching goals. (See Chapter 2 Healthy People box.) When accessed via the interactive site, each of the 42 topic areas includes goals, objectives, interventions and resources as well as links to screening recommendations by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF, 2011, http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org) when indicated. Each topic area is assigned to one or more lead agencies within the federal government that is responsible for developing, tracking, monitoring and reporting on objectives. Leading Health Indicators have been selected to monitor progress for 12 priority topic areas. (See Chapter 2 Healthy People box.) Also, four foundation health measures that accompany the overarching goals will be used to monitor progress toward promoting health, preventing disease and disability, eliminating disparities, and improving the quality of life. (See the Healthy People 2020 box below.)

Using the interactive Healthy People website, users can track the progress of objectives in each of the 42 topic areas. Data to monitor progress are obtained from national surveys such as the National Health Interview Survey or the National Vital Statistics System. If national data are not available, state or area data are used to monitor the objective. Some of the objectives are measurable—meaning they contain data sources and national baseline values. Other objectives are developmental—meaning they currently do not have national baseline data but will ultimately have data and tracking points. Detailed instructions on accessing the data are available on the website.

Two specific examples of focus areas with detailed data that have continued to be part of the Healthy People publications over the three decades of data collection include (1) physical activity and fitness and (2) nutrition and overweight.

In the focus area of physical activity, baseline data and improvements with references to the 2010 data can be found for objectives targeting the numbers of adults who engage in aerobic physical activity. A 10% improvement over the baseline from the National Health Interview Survey is the target for this measure. Detailed data for various age groups is available. Related to nutrition and overweight, detailed analysis reveals that Americans are moving away from the target of achieving a healthy weight. Links to community interventions and clinical recommendations and consumer resources are provided and are a useful tool for practicing community/public health nurses.

Funding for prevention efforts such as those to promote physical activity and achieve a healthy weight are meant to help decrease the cost of chronic disease such as cardiovascular disease, which is directly related to obesity and lack of physical activity. Estimated costs for cardiovascular disease and stroke in 2005 were $394 billion. The estimated health costs related to the 1 in 3 adults who were obese in 2008 was $147 billion. Notable also is data indicating that from 1980 to 2008, obesity tripled for children—nearly 17% of U.S. children are obese (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011a). The importance of health-promotion programs and the need for individual and community commitment to health-promoting lifestyle changes cannot be overstated.

Health promotion is a major goal of community/public health nursing practice (American Nurses Association [ANA], 2007). Community/public health nurses facilitate health in the population through direct nursing interventions for health promotion and disease prevention with individuals, families, groups, and populations. The American Nurses Association (ANA) (1995) position statement on health promotion and disease prevention suggests specific nursing activities to influence comprehensive health-promotion services (Box 18-1).

In this chapter, the concept of health is explored in depth, and major influences on health are examined. Theoretical models are presented that attempt to explain health-related behaviors. National policies related to health promotion and risk reduction are reviewed, and types of health-promotion and risk-reduction/health-protection programs are examined. Finally, the responsibilities of the community/public health nurse in facilitating health promotion are explored using the nursing process.

Meaning of health

The concept of health has been defined in a variety of ways. Historically, health and illness were viewed as extremes on a continuum, with the absence of clinically recognizable disease being equated with the presence of health. In 1947 the World Health Organization (WHO) defined health in terms of total well-being and discouraged the conceptualization of health as simply the absence of disease. In 1995 the WHO launched a process known as “Health for All,” which is aimed at preparing countries to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century and emphasizes the need to see health as central to human development and societal growth. In 2003, the United States launched an initiative from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) known as Steps to a Healthier US Initiative (2007), to improve the lives of Americans through community-based chronic disease-prevention programs. (This program is now called the Healthy Communities Program within the CDC.) Further progress has been made to weave health and preventive practices in all aspects of our lives including how we live, where we work, our ability to access clean water and safe food, and how we spend leisure time. In June 2011, the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council announced the release of the National Prevention Strategy as America’s plan for better health and wellness. Using the goals set forth in Healthy People 2020, this National Prevention Strategy (2011) establishes a cohesive federal response that focuses on prevention and prioritizes interventions that will prevent the leading causes of death such as obesity and tobacco use. The Strategy’s seven priorities are the following:

• Preventing drug abuse and excessive alcohol use

• Injury and violence free living

• Reproductive and sexual health

The strategy is also designed to strengthen collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors including businesses, community groups, and health care organizations.

More contemporary definitions of health have emphasized the relationship between health and wellness and health promotion. Although health may be viewed as a static state of being at any given point in time, wellness is the process of moving toward integrating human functioning and maximizing human potential. Health promotion is the process of helping people enhance their well-being and maximize their human potential. The focus of health promotion is on changing patterns of behavior or environmental structures to promote health rather than simply to avoid illness. The goal of health promotion is to enable people to exercise control over their well-being and ultimately improve their health, focusing on persons and populations as a whole and not solely on people who are at risk for specific diseases. Health promotion combines education, organizational involvement, economics, and political influences to bring about changes in behaviors of individuals and groups or changes in environmental structures related to improved health and well-being (Cohen et al., 2000; O’Donnell, 1986). This classic definition of health promotion remains pertinent and today the terms wellness and health promotion are frequently used interchangeably, with both terms having elements of physical, mental, and social well-being for both the individual and the community.

Determinants of health

Many factors, including lifestyle, genetics, and the environment, influence health. Lifestyle refers to the way people live their lives and involves patterns of working, playing, eating, sleeping, and communicating. A healthy lifestyle is easier to maintain when healthful patterns of behavior are learned early in life. Therefore the family plays a critical role in developing health beliefs and behaviors, such as exercise patterns, sound nutritional practices, regular use of seat belts, avoidance of harmful substances (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, drugs), stress management, and routine medical and dental evaluations.

Biological Influences

Genetic endowment influences susceptibility to illness. Familial tendencies toward diseases such as diabetes and heart disease are well established. However, illnesses related to genetics may also be influenced by cultural and environmental factors. Similarly, genetic features such as height and weight may be environmentally influenced. Thus, because many of these factors exist or operate simultaneously, determining the relative influence of genetics and the environment on the risk of developing disease is often difficult.

Environmental Influences

Environmental influences also contribute to or detract from the ability of people to develop to their optimal potential. When examining environmental influences on health, the physical and sociocultural environments must be considered. Factors in the physical environment that influence health include weather and climatic conditions, noise, light, air, food, water, and exposure to toxic substances. According to Healthy People 2020, an estimated 25% of preventable illnesses worldwide can be attributed to poor environmental quality (see Chapter 9).

Factors in the sociocultural environment that influence health include the historic era in which one lives, values of family and significant others, social institutions (e.g., governments, schools, faith communities), socioeconomic class, occupation, and social roles that encourage or diminish the importance of preventive health practices. For example, an industrial worker may be exposed to toxic or carcinogenic substances that render him susceptible to different types of illness. In addition, health resources may be available only in more affluent communities, which diminish access to services by persons of lower socioeconomic status. In the United States, higher education and higher socioeconomic class are associated with greater participation in health-promotion activities (see Chapter 10). All who live in America “should have the opportunity to make the choices that allow them to live a long, healthy life. . . .” (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010, p. 8).

The health care system is another important aspect of the environment that must be considered when determining the health potential of a society. Health care systems focus (in varying degrees) on prevention, cure, and rehabilitation in an effort to improve the health of society. The ability to access health care impacts the overall health of individuals and groups. Access to care also impacts the prevention of disease and the early detection of health conditions leading to a better quality of life and improves life expectancy. Access to Health Services is one of the topic areas in Healthy People 2020. Barriers to accessing health care include high cost, lack of accessibility, and lack of insurance coverage. People with health insurance are more likely to have appropriate preventive health care screenings, such as a Papanicolaou (Pap) test, immunizations, or early prenatal care. The uninsured are more likely to have poor health status. The target for Healthy People 2020 is for 100% of the population to have health insurance (83.2% had medical insurance in 2008) and to increase the percent of people having a specific primary care provider. There are numerous developmental goals in the Access to Health Services topic area including increasing the number of persons having insurance coverage for clinical preventive services. In March 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act became law and provided structure for efforts to provide accessible and affordable care for all, including helping more children get health coverage, ending lifetime and annual insurance limits, giving patients access to recommended preventive services, and discounting prescription medications for seniors and programs to reduce health disparities. More information about the Affordable Care Act is available at the new interactive website http://www.healthcare.gov. (See Chapters 3 and 6.) A lack of health care and primary preventive services has a tremendous impact on the health of a society (see Chapter 21). For this reason, current emphasis is on creating public and private partnerships to bridge the gap in service availability.

Health services may be directed toward primary, secondary, or tertiary levels of prevention. Primary prevention is aimed at preventing the onset of disease or disability by reducing risks to health, decreasing vulnerability to illness, and promoting health and well-being. Secondary prevention is aimed at diagnosis and treatment of illness at an early stage, thereby halting further progression of disease and assisting persons to return to normal functioning. Secondary prevention includes case finding for individuals and screening of high-risk groups for the presence of disease. Tertiary prevention focuses on the restoration of optimal functioning once a condition becomes irreversible by limiting the extent of disability that may occur and by assisting clients to function at an optimal level within the constraints of their existing disabilities. The focus of this chapter is on primary prevention to promote health and prevent illness in an individual, family, or community. Chapter 7 provides additional detail on levels of prevention.

National policy

Health promotion is a social project, not solely a medical enterprise. Societies have a political responsibility to strengthen the link between health and social well-being. An integration of government, major interest groups (environmental, business, industrial, medical, labor, educational), and community forces is needed to establish and maintain public policy and community action that promotes the health of individuals, families, and communities in society. The ability of the health care system to engage in health promotion is often determined by national legislation such as the previously mentioned Affordable Care Act of 2010 and policies that provide economic and political support for health-promotion services in the community.

Focus on Health Promotion

Healthy People, the first U.S. Surgeon General’s report on health promotion and disease prevention, was instrumental in identifying major health problems of the nation and in setting national goals for reducing death and disability. The central message of this report is a message that has not changed over the decades: the health of the nation can be improved by individual and collective action in public and private sectors and by promoting a safe, healthy environment for all Americans (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, 1979).

In 1980, the USDHHS published a second document entitled Promoting Health/Preventing Disease: Objectives for the Nation. This document set forth specific objectives for meeting the national health care priorities established in the Surgeon General’s report. Subsequent reports leading up to the most current publication, Healthy People 2020, included priorities such as reduction in hypertension, decrease in chronic disease including cardiovascular disease and diabetes, increase in immunizations, reduction in sexually transmitted diseases, improved access to preventive health services, accident prevention, and reduction in smoking and alcohol and drug abuse. The Healthy People reports and objectives are designed to improve the health of the nation through a management-by-objective planning process.

Healthy People 2020 builds on the accomplishments of previous decades and includes new and pertinent topic areas such as Dementias including Alzheimer Disease, Healthcare-Associated Infections, Preparedness, Global Health and others. Healthy People 2020 is a compilation of years of data collection and input from a diverse group of individuals and organizations. Healthy People 2020 topic areas include objectives for identified target populations and links to activities and interventions for health promotion, health protection, and clinical preventive services. Additionally, the 2020 objectives are data driven and are supported by scientific evidence. Healthy People 2020 also involves some non–health sectors that also are determinants of health, such as agriculture, education, housing, and transportation. The Healthy People 2020 box below presents objectives targeting selected health-promotion activities.

National Health Care Surveys

Numerous federal resources are available to obtain information on health care statistics and health surveys. Comprehensive historical and current data supporting the objectives and interventions relating to Healthy People 2020 are incorporated into each topic area. The site is linked directly to data sources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and the National Health Care Survey (NHCS). The NHCS is the nation’s primary health statistics website, which includes data from a group of surveys, including information about health care services and characteristics of the clients served and other national vital statistics, including morbidity and mortality data (see Chapter 7). Additionally, the CDC provides statistical data on chronic health problems (e.g., cardiovascular health) and preventable problems (e.g., tobacco-related disease). Most notable in the chronic disease overview on the CDC website is information related to the costs of chronic disease and the cost-effectiveness of prevention. The U.S. Public Health Service Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) coordinates the efforts of public and private sectors to reduce the risks of disease and promote the nation’s health. Accessing the ODPHP website (http://www.odphp.osophs.dhhs.gov) provides the user with links to Healthfinder.gov, Healthy People 2020, Health.gov and Dietary Guidelines for Americans. It is almost a one-stop-shop for accessing health information for consumers and professionals including communication tools, information on health literacy, and links to federal information centers and clearinghouses. (See Community Resources for Practice at the end of this chapter for access to these websites.)

Health models

Biological, environmental, and sociocultural factors can influence health status. These multiple influences on health ultimately determine the type and extent of personal health behaviors. A variety of conceptual models have been proposed in an attempt to describe, explain, or predict preventive health behaviors.

Health-Belief Model

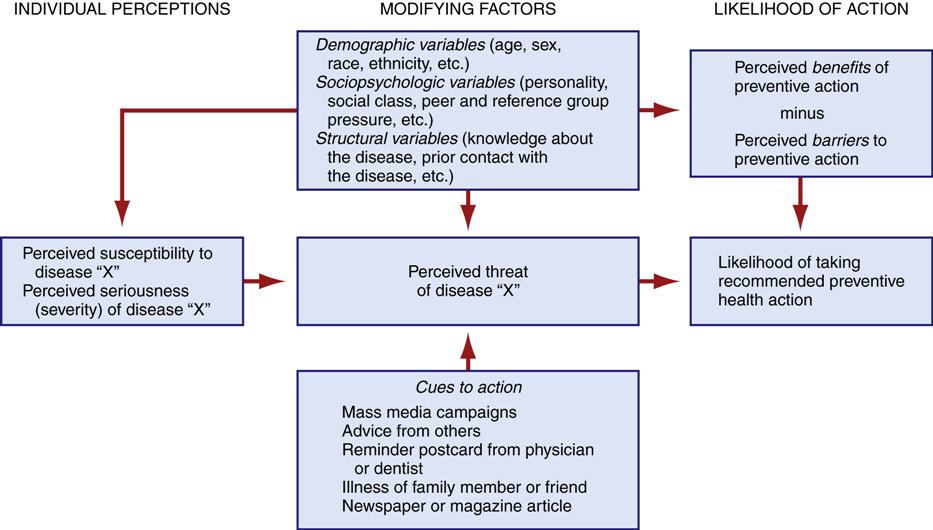

The health-belief model, which has been widely used to explain wellness and illness behaviors, was created in the 1950s and has since been revised and tested extensively (Becker, 1974; Becker et al., 1977; Hochbaum, 1956; Rosenstock, 1974). Proponents of the health-belief model contend that individuals will take action to avoid disease states. Actions are motivated by (1) the sense of personal susceptibility to a disease, (2) the perceived severity of a disease, (3) the perceived benefits of preventive health behaviors, and (4) the perceived barriers to taking actions to prevent a disease. Potential barriers include fear, pain, cost, inconvenience, and embarrassment (Rosenstock, 1974).

The client’s perception of health status and the value placed on taking preventive action may also be affected by demographic variables (e.g., age, gender, race, ethnicity), sociopsychological variables (e.g., social class, peer pressure, attitude toward medical authorities), and structural variables (e.g., personal experience with disease, knowledge of disease). Internal cues (e.g., detecting a breast lump) or external cues (e.g., advice from significant others, exposure to a media campaign) can also serve to motivate healthful behaviors (Figure 18-1).

Empirical research demonstrates that the attitude and belief dimensions of the health-belief model do predict individuals’ health-related behavior. When an illness or injury is perceived to be serious and barriers are low, individuals are more likely to seek medical care and follow the suggested treatment. In addition, individuals are more likely to engage in preventive health behavior when barriers to care are low and when people perceive that they are susceptible to an illness or injury (Janz & Becker, 1984). These two components of the model, perceived barriers and perceived susceptibility, appear to be the most important variables for health-promotion intervention. Additional study of the model led to a proposal to include self-efficacy in the health-belief model as a way to help explain health-protective behaviors (Rosenstock et al., 1988). Self-efficacy is the belief of an individual that he or she can perform, or learn to perform, a specific activity or behavior (see Chapter 20).

In addition to helping clients decrease barriers to health promotion, nurses can also use the health-belief model to identify the need for specific programs for at-risk groups. Two studies related to nursing interventions to reduce the risk of osteoporosis included the importance of health beliefs as a component of the nursing intervention (Sadler & Huff, 2007; Sedlak et al., 2005). In both studies, the intervention to reduce perceived barriers to calcium intake and exercise was an educational intervention that incorporated cultural differences and health beliefs as a method to change behavior to reduce osteoporosis risk. The importance of the nursing responsibility to address health beliefs is emphasized as a health-protecting behavior.

The health-belief model is driven more by health-protecting behaviors than it is health-promoting behaviors. Health-protecting behaviors are those that protect people from problems that jeopardize their health and well-being such as in the osteoporosis examples previously provided. Immunizing the population against infectious diseases and reducing exposure to environmental health hazards are examples of health-protecting behaviors. Health-promoting behaviors are those that improve health by fostering personal development or self-actualization. Many health behaviors, such as managing dietary intake, exercise, and stress management, serve a dual function by being both health-promoting and health-protecting.

Health-Promotion Model

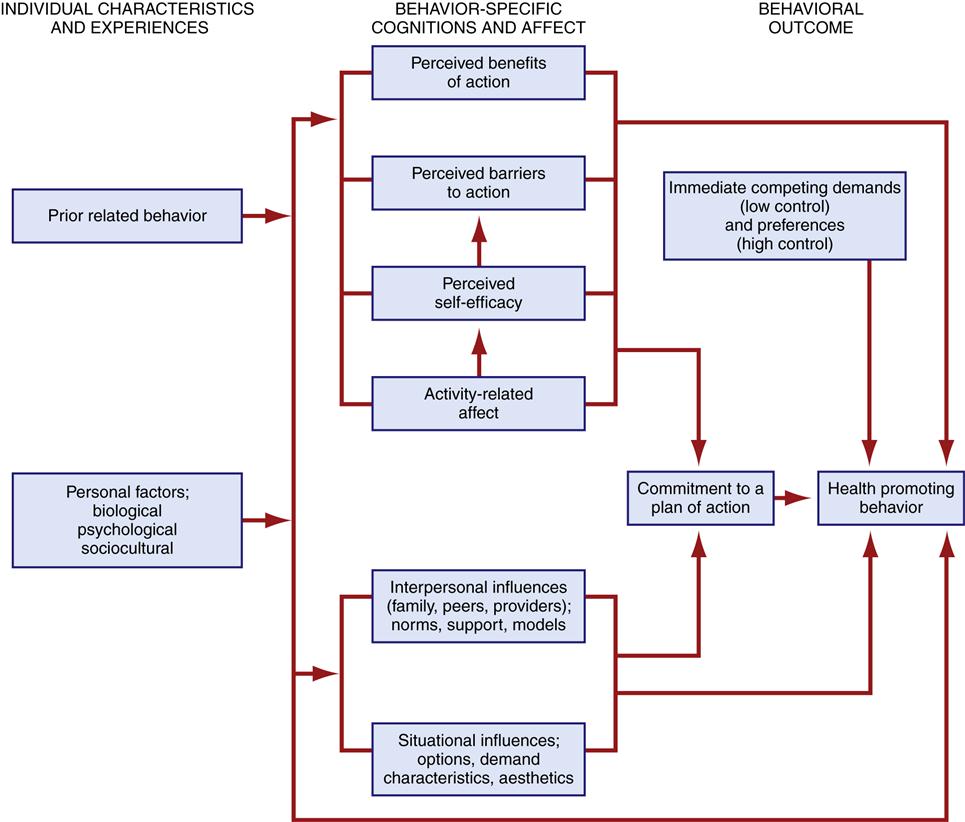

Whereas the health-belief model may account for actions taken to prevent disease, Pender and colleagues (2006) proposed a revised health-promotion model that attempts to account for health-promoting behaviors that improve well-being and develop human potential. Pender and associates (2006) contended that health-promotion behaviors are determined by the following factors:

Pender’s model represents a multitude of factors affecting health-promotion behavior, which is the end point, or outcome, of the health-promotion model (Figure 18-2).

A clinical example of the importance of eliminating barriers is examined in a study of healthy eating behaviors in women underserved by the health care system (Timmerman, 2007). In this population, the barriers to healthy eating included individual characteristics, experience, and culture. The barriers were internal, interpersonal, and environmental and were seen to overlap to impede healthy eating. Interventions to improve health-promoting behaviors included individualizing the interventions (removal of internal barriers) while working with the community (removal of environmental barriers) to develop a plan of action that was broad enough to be applicable to the larger population. Additional interventions included facilitating changes in public policy to eliminate barriers faced by underserved women (Timmerman, 2007).

Primary Health Care Model

Another way to view health and its relationship to individuals is the primary health care model proposed by Shoultz and Hatcher (1997) (Figure 18-3). The focus of the model is health care for all members of the community, with a multisectoral approach. The model should not be confused with primary care or with personal health services, which address health care for individuals. Primary care services may be delivered in a community setting (e.g., clinic, school) but do not necessarily influence the health of the community. The primary health care model embodies the principles of community participation and a multisectoral approach with an emphasis on prevention. The six key elements of environment, health services, education and communication, politics, economics, and agriculture and nutrition surrounding the health of the community are interlinked, and each element has an impact on health. Important to note is that the delivery of personal health care to individuals is a component of health services. The model for primary health care provides a format for community/public health nurses to promote health and health education related to community influences and the environment. The model may also be adapted if necessary to add other sectors to the influences on health, such as the impact of spirituality on community health.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>