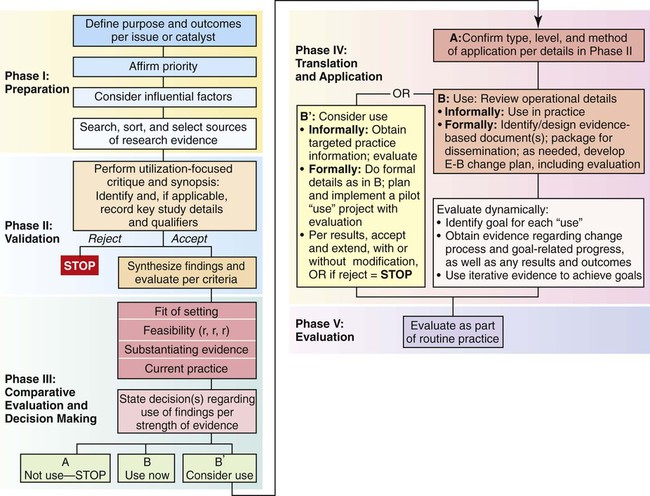

• Value the individual nurse’s obligation to use research in practice. • Analyze the differences among research utilization, evidence-based practice, and practice-based evidence. • Formulate a clinical question that can be searched in the literature. • Evaluate resources for the best available evidence. • Identify resources for critically appraising evidence. • Assess organizational barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of research findings. • Identify strategies for translating research into practice within the context of an organization. Research is an integral part of professional practice. Research is the “diligent, systematic inquiry or investigation to validate and refine existing knowledge and generate new knowledge” (Burns & Grove, 2009, p. 2). Nurses, as professionals, have an obligation to society that involves rights and responsibilities as well as a mechanism for accountability. These obligations are outlined in Nursing’s Social Policy Statement: The Essence of the Profession developed by the American Nurses Association (ANA, 2010) and includes: “To refine and expand nursing’s knowledge base, nurses use theories that fit with professional nursing’s values of health and health care that are relevant to professional nursing practice. Nurses apply research findings and implement the best evidence into their practice … (p. 13). The Code of Ethics for Nurses (ANA, 2001, p. 22) directs that the “nurse participates in advancement of the profession through contributions to practice, education, administration and knowledge development.” Furthermore, the global importance of nursing research is illustrated by an International Council of Nurses’ (ICN) position statement indicating support for “national nurses’ associations in their efforts to enhance nursing research, particularly through improving access to education which prepares nurses to conduct research, critically evaluate research outcomes and promote appropriate application of research findings to nursing practice” (2007, p. 3). Nursing research is designed to refine and expand the scientific foundation for nursing, which is defined as the “protection, promotion, and optimization of health and abilities, prevention of illness and injury, alleviation of suffering through the diagnosis and treatment of human response, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and population” (ANA, 2003, p. 6). The practice of nursing draws on nursing science and the physical, economic, biomedical, behavioral, and social sciences (ANA, 2010). Therefore all nurses need to apply findings of nursing research and research conducted by members of other disciplines that have relevance for their own practice. The translation of research into practice involves all healthcare disciplines. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) created a roadmap to harness scientific discovery to improve the health of all people. The roadmap has three major themes: (1) new pathways to discovery, (2) research teams of the future, and (3) re-engineering the clinical research enterprise (NIH, n.d.). The focus of new pathways to discovery is on new strategies for diagnosing, treating, and preventing disease. It includes building blocks, biologic pathways and networks, molecular libraries and imaging, structural biology, bio-informatics and computational biology, and nanomedicine. The research teams of the future focus on high-risk research, interdisciplinary teams, and public-private partnerships. Re-engineering the clinical research enterprise focuses on clinical research networks, policy analysis and coordination, dynamic assessment of patient-reported chronic disease outcomes, and translational research. The emphasis is getting research into the hands of practitioners who use it to better patient care. The oft-quoted statistic of taking 17 years to apply research discoveries to clinical practice (Balas & Boren, 2000) suggests that healthcare professionals need to accelerate the integration of research with practice. Research indicates that adults in the United States receive only 54.9% of recommended care (Asch et al., 2006). We might believe that once a research study is published in a journal, clinicians read it immediately and then nurses and/or policymakers use it to improve practice. Often, that is not the case. For example, Norma Metheny has been researching techniques for testing nasogastric tube placement for many years. She and her colleagues demonstrated that relying on listening to the “swoosh” sound with a stethoscope to determine correct placement could be dangerous. Her recommendation is to test gastric contents for pH, with a pH of 0 to 4 indicating gastric placement. When the pH is greater than 4, additional testing of the aspirate for bilirubin or pepsin at the bedside is recommended. Yet, many nurses may not be familiar with the technique, nor do they have access to point-of-care testing methods (Metheny & Titler, 2001). The American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN) practice alert (2005) draws heavily on Metheny’s work, recommending radiographic confirmation for the initial indicator of placement. Metheny’s research has also been incorporated into recommendations for enteral nutrition (Bankhead et al., 2009). EBP promotes the use of effective strategies to help patients and helps nurses stop the use of ineffective strategies that might harm patients. Research provides the foundation for nursing practice improvement. Examples include preoperative teaching, pain management, child development assessment, falls prevention, pressure-ulcer risk detection, incontinence care, and family-centered care in critical care units. Nurses need to systematically evaluate nursing studies to decide what interventions should be implemented to improve the outcomes of care. Practices that were once thought to be the standard of care may quickly become outdated. Some practices may have been carried out for many years without ever being examined for their scientific basis or effectiveness. The latest research findings need to be incorporated into procedures using an evidence-based model when they are being updated by an organization. The Evidence section on pp. 430–431 illustrates how research can be incorporated into organizational practices. Research utilization is the process of synthesizing, disseminating, and using research-generated knowledge to influence or change existing practices (Burns & Grove, 2009). Research utilization is different from, but complementary to, research. Although individual nurses may apply research findings to their own practice, nurses’ broader responsibility to society includes activating the change process in translating research into practice. Research use can be in a variety of forms: enlightenment, implementation of a research-based protocol, or the widespread adoption of standards based on research findings. Ultimately, multiple factors influence how a particular research finding is adopted, translated into practice, and sustained in practice. Nurse researchers have a distinguished record of facilitating research utilization in clinical practice that has gone beyond dissemination through publication in research journals. In the 1970s, three major federally funded projects facilitated research utilization: the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education in Nursing (WICHEN) project, 1975; the Conduct and Utilization of Research in Nursing (CURN) project at the University of Michigan, 1976; and the Nursing Child Assessment Satellite Training (NCAST), 1976 to 1985. These early initiatives spawned the growth of many demonstration projects in an effort to implement research findings in practice, as well as research studies conducted to identify factors that facilitate or create barriers to research utilization. The NCAST program illustrates the far-reaching and enduring effect of research utilization. This program, developed by Kathryn Barnard in 1976, is widely used today by home health nurses and public health departments across the country and even internationally (NCAST Programs, 2007). More than 21,000 healthcare professionals have been trained in the use of the NCAST assessment materials, with 200 of them actively providing education at any given time. Many research utilization models in nursing were developed in the 1970s and 1980s. One of the first was the Stetler-Marram model developed in 1976, which now includes the facilitation of EBP (Stetler, 2001). Other models developed by nurses are listed in Table 21-1. TABLE 21-1 Stetler’s research utilization model (2001) provides direction for an individual and for group members. It has implications for nurses in leadership roles responsible for patient care management. According to Stetler, the preparatory steps of research utilization sustain EBP. Stetler’s model consists of five phases: preparation, validation, comparative evaluation/decision making, translation/application, and evaluation (Figure 21-1). The preparatory phase involves searching, sorting, and selecting sources of evidence, defining external factors influencing the application of a research finding, and defining internal factors diminishing objectivity. The second phase, validation, focuses on utilization with an appraisal of study findings rather than the critique of a study’s design. This phase includes completing review tables to facilitate understanding each study and to facilitate decision making. The third phase, comparative evaluation and decision making, involves making a decision about the applicability of the studies by synthesizing cumulative findings; evaluating the degree and nature of other criteria, such as risk, feasibility, and readiness of the finding; and actually making a recommendation about using the research. The fourth phase, translation and application, involves practical aspects of implementing the plan for translating the research into practice at the individual, group, department, or organizational level. Multiple strategies are recommended for the implementation of change. It is important to be sure that translating the research finding into practice does not exceed what the evidence warrants. The last phase includes an evaluation, which can be informal or formal and may include a cost-benefit analysis. Evaluation can include whether the research innovation was implemented as intended and goal achievement. Stetler’s model focuses heavily on the change process to facilitate the successful translation of research into practice. Evidence-based practice (EBP) is the integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and the patient’s unique values and circumstances in making decisions about the care of individual patients (Straus, Richardson, Glasziou, & Haynes, 2005). Ingersoll (2000, p. 151) developed one of the first definitions for evidence-based nursing practice: “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of theory-derived, research-based information on making decisions about care delivery to individuals or groups of patients and in consideration of individual needs and preferences.” In EBP, clinical problems drive the search for solutions based on the best available evidence, which is then translated into practice. EBP is a broader, more encompassing view of research utilization. It is focused on searching for and evaluating the best evidence to address a particular clinical practice problem. The role of the organization in implementing evidence-based practice is illustrated by Brown (2008) in the Literature Perspective below. EBP, including evidence-based medicine, is derived from the work of Archie Cochrane. He described the lack of knowledge about healthcare treatment effects and advocated for the use of proven treatments. Subsequently, the Cochrane Collaboration was established at Oxford University in 1993. About that time, Gordon Guyatt and his colleagues at McMaster University authored a series of articles in the Journal of the American Medical Association known as the Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature. These provided a foundation for teaching evidence-based medicine. Since then, the EBP movement has grown exponentially with the establishment of centers, resources on the Web, and grants given specifically to advance the translation of research into practice. A number of evidence-based nursing centers have been established around the world. The Joanna Briggs Institute, based in Australia, has a network of collaborating centers and evidence-based synthesis and utilization groups around the world. These centers have teams of researchers who critically appraise evidence and then disseminate protocols for the use of evidence in practice. Resources for evidence-based health care are listed in Box 21-1. Many nursing education programs incorporate EBP into their curricula. Various organizations have developed evidence-based standards of practice and clinical guidelines. The American Association of Neuroscience Nurses (2007) developed a series of practice guidelines, including one about the nursing management of adults with severe traumatic brain injury. Guidelines developed by the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses have been tested for their cost-effectiveness and efficiency (Berry, Wick, & Magons, 2008). The Oncology Nursing Society and the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario have developed toolkits for EBP. The American Heart Association’s Council on Cardiovascular Nursing participates in interdisciplinary teams for guideline development. Many of these guidelines produced by evidence-based centers and other professional groups are available either online on the organization’s website or through the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Societal factors, such as the rising cost of health care, quality improvement initiatives, and the pressures to avoid errors, have resulted in an increased emphasis on research as a basis for practice decisions. Nurses and other healthcare professionals are called upon to use evidence in practice in the midst of an exponentially expanding scientific knowledge base. The Institute of Medicine calls for all healthcare professionals to be educated in EBP. Specifically, professionals should be able to do the following (Greiner & Knebel, 2003): • Know where and how to find the best possible sources of evidence • Formulate clear clinical questions • Search for relevant answers to those questions from the best possible sources, including those that evaluate or appraise evidence for its usefulness with respect to a particular patient or population • Determine when and how to integrate those findings into practice Nursing research exists on a continuum, and not all research is ready for, or of a quality that is appropriate for, implementation, or it may not be ready for implementation in a particular setting. However, the quality of care and the quality of the outcomes of care can be dramatically improved with the implementation of evidence-based nursing practices. Nurses are heeding the call to develop evidenced-based practices. Nurse leaders and managers have a critical responsibility in promoting the use of the best evidence for practice. Resources for evidence-based nursing are listed in Box 21-2. With the growth of large databases, the use of electronic health records, and sophisticated statistical techniques, it is increasingly possible to examine practices in real-world situations and evaluate the comparative effectiveness of interventions. Practice-based evidence–clinical practice improvement (PBE-CPI) is a research methodology that helps inform practice decisions by examining outcomes in the real world in which patients may not be similar and the actual application of an intervention may have multiple variations. A PBE-CPI project will (1) compare clinically relevant interventions, (2) include diverse study participants, (3) use heterogeneous practice settings, and (4) collect data on a broad range of health outcomes (Horn & Gassaway, 2007). The National Pressure Ulcer Long-term Care Study (NPULS) used this methodology at 95 facilities to identify interventions associated with decreased likelihood of pressure ulcer development (Bergstrom et al., 2005). Subsequently, the interventions were refined and implemented consistently. This resulted in a 65% decrease in the development of new pressure ulcers. Similarly, the National Database of Nursing’s Quality Indicators® established by the ANA (n.d.) collects quarterly data on nursing quality indicators and annually surveys nurse job satisfaction and work environment. Hospitals receive comparative reports and can design evidence-based practice improvement projects with outcomes measured using a standard methodology. These methodologies used together with results of clinical trials can be used to enhance patient care. The now classic theory of diffusion of innovations (Rogers, 2003) describes how innovations spread through society, occurring in stages: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and confirmation. This theory, highlighted in the Theory Box below, provides a useful model in planning for the integration of evidence into practice over time. An intervention’s characteristics can influence its adoption. These include the relative advantage (whether it is better than what it replaces), compatibility (consistency with values, experiences, needs), complexity (difficulty in understanding its use), trialability (the degree to which it can be easily tested), and observability (the ease of seeing the results) (Rogers, 2003). Widespread media attention to a particular finding can be instrumental in the adoption of a practice change. Extensive publicity accompanied the publication of a study about family presence during emergency procedures and resuscitation (Meyers et al., 2000). Publication of the study was accompanied by press releases and television news stories. Since then, the research was replicated and expanded to other settings (Smith, Hefley, & Anand, 2007), thus strengthening the scientific basis for the innovation and facilitating the practice of allowing families to be present during resuscitation. Hatfield, Gusic, Dyer, and Polomano (2008) found that the administration of oral sucrose to babies receiving their 2-month and 4-month immunizations reduced their pain scores. Their study received wide publicity in media outlets. Thus parents were alerted about the importance of asking that this simple pain management strategy be implemented for their infants when being immunized. Nurse researchers write clinical articles in addition to research articles. Many journals that are directed toward clinicians provide nurses with easy-to-understand summaries of studies from the general healthcare and nursing research literature. Nursing schools develop press releases when researchers publish studies, which are then used by the media for their news articles. For example, Rachel Jones (2008) conducts research on the use of urban soap opera videos delivered on a handheld device to convey messages about HIV risk reduction in young adult urban women. Publicity in various media outlets in the community, her receipt of a New York Times award, and a website (www.stophiv.newark.rutgers.edu/) increase visibility of this important public health problem.

Translating Research into Practice

Introduction

Research Utilization

MODEL

SELECTED SOURCE

Dracup-Breu (WICHEN Project)

Dracup, K.A., & Breu, C.S. (1978). Using nursing research findings to meet the needs of grieving spouses. Nursing Research, 27, 212-216.

Goode Research Utilization Model

Goode, C.J., Lovett, M.K., Hayes, J.E., & Butcher, L.A. (1987). Use of research-based knowledge in clinical practice. Journal of Nursing Administration, 17(12), 11-18.

Quality Assurance Model Using Research

Watson, C.A., Bulecheck, G., & McCloskey, J. (1987). QAMUR: A quality assurance model using research. Journal of Nursing Quality Assurance, 2(1), 21-27.

University of North Carolina Model

Funk, S.G., Tornquist, E.M., & Champagne, M.T. (1989). A model for improving the dissemination of nursing research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 11(3), 361-372.

Multidimensional Framework of Research Utilization

Kitson, A., Harvey, G., & McCormack, B. (1998). Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework. Quality in Health Care, 7, 149-158.

Change to Evidence-Based Practice Model

Rosswurm, M.A., & Larrabee, J.H. (1999). A model for change to evidence-based practice. Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 31, 317-322.

Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice to Promote Quality of Care

Titler, M.G., Kleiber, C., Steelman, V.J., Rakel, B.A., Budreau, G., Everett, L.Q., Buckwalter, K.C., Tripp-Reimer, T., & Goode, C.J. (2001). The Iowa model of evidence-based practice to promote quality care. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America, 13, 497-509.

Collaborative Research Utilization Model

Dufault, M. (2004). Testing a collaborative research utilization model to translate best practices in pain management. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(3), S26-S32.

Ottawa Model of Research Use

Graham, K., & Logan, J. (2004). Using the Ottawa model of research use to implement a skin care program. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19, 18-24.

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS)

Rycroft-Malone, J. (2004). The PARIHS Framework: A framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 19, 297-304.

Evidence-Based Practice

Practice-Based Evidence

Diffusion of Innovations

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nurse Key

Fastest Nurse Insight Engine

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access