On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Identify parental and infant behaviors that facilitate and those that inhibit parental attachment. • Describe sensual responses that strengthen attachment. • Compare maternal adjustment and paternal adjustment to parenthood. • Describe ways in which the nurse can facilitate parent-infant adjustment. • Examine the effects of the following on parenting responses and behavior: parental age (i.e., adolescence and older than 35 years), same-sex parenting, social support, culture, socioeconomic conditions, personal aspirations, and sensory impairment. • Describe sibling adjustment. The process by which a parent comes to love and accept a child and a child comes to love and accept a parent is known as attachment. Using the terms attachment and bonding, Klaus and Kennell (1976) originally proposed that there is a sensitive period during the first few minutes or hours after birth when mothers and fathers must have close contact with their infant to optimize the child’s later development. Klaus and Kennell (1982) later revised their theory of parent-infant bonding, modifying their claim of the critical nature of immediate contact with the infant after birth. They acknowledged the adaptability of human parents, stating that more than minutes or hours were needed for parents to form an emotional relationship with their infants. The terms attachment and bonding continue to be used interchangeably. Attachment is developed and maintained by proximity and interaction with the infant through which the parent becomes acquainted with the infant, identifies the infant as an individual, and claims the infant as a member of the family. Attachment is facilitated by positive feedback (i.e., social, verbal, and nonverbal responses, whether real or perceived, that indicate acceptance of one partner by the other). Attachment occurs through a mutually satisfying experience. A mother commented on her son’s grasp reflex, “I put my finger in his hand, and he grabbed right on. It is just a reflex, I know, but it felt good anyway” (Fig. 20-1). The concept of attachment includes mutuality; that is, the infant’s behaviors and characteristics elicit a corresponding set of maternal behaviors and characteristics. The infant displays signaling behaviors such as crying, smiling, and cooing that initiate the contact and bring the caregiver to the child. These behaviors are followed by executive behaviors such as rooting, grasping, and postural adjustments that maintain the contact. Most caregivers are attracted to an alert, responsive, cuddly infant and repelled by an irritable, apparently disinterested infant. Attachment occurs more readily with the infant whose temperament, social capabilities, appearance, and sex fit the parent’s expectations. If the child does not meet these expectations, the parent’s disappointment can delay the attachment process. Table 20-1 presents a comprehensive list of classic infant behaviors affecting parental attachment. Table 20-2 presents a corresponding list of parental behaviors that affect infant attachment. TABLE 20-1 Infant Behaviors Affecting Parental Attachment Data from Gerson E: Infant behavior in the first year of life, New York, 1973, Raven Press. TABLE 20-2 Parental Behaviors Affecting Infant Attachment Data from Mercer R: Parent-infant attachment. In Sonstegard L, Kowalski K, Jennings B, editors: Women’s health (vol 2), New York, 1983, Grune & Stratton. An important part of attachment is acquaintance. Parents use eye contact (Fig. 20-2), touching, talking, and exploring to become acquainted with their infant during the immediate postpartum period. Adoptive parents undergo the same process when they first meet their new child. During this period, families engage in the claiming process, which is the identification of the new baby (Fig. 20-3). The child is first identified in terms of “likeness” to other family members, then in terms of “differences,” and finally in terms of “uniqueness.” The unique newcomer is thus incorporated into the family. Mother and father examine their infant carefully and point out characteristics that the child shares with other family members and that are indicative of a relationship between them. The claiming process is revealed by maternal comments such as “Daniel held him close and said, ‘He’s the image of his father,’ but I found one part like me—his toes are shaped like mine.” Nursing interventions to facilitate parental attachment are numerous and varied (Table 20-3). They can enhance positive parent-infant contacts by heightening parental awareness of an infant’s responses and ability to communicate. As the parent attempts to become competent and loving in that role, nurses can bolster the parent’s self-confidence and ego. Nurses can identify actual and potential problems and collaborate with other health care professionals who will provide care for the parents after discharge. Nursing considerations for fostering maternal-infant bonding among special populations may vary (see Cultural Competence box). TABLE 20-3 Examples of Parent-Infant Attachment Interventions Data from Bulechek G, Butcher H, Dochterman J, et al: Nursing interventions classification (NIC), ed 6, St Louis, 2013, Mosby. One of the most important areas of assessment is careful observation of specific behaviors thought to indicate the formation of emotional bonds between the newborn and family, especially the mother. Unlike physical assessment of the neonate, which has concrete guidelines to follow, assessment of parent-infant attachment relies more on skillful observation and interviewing. Rooming-in of mother and infant and liberal visiting privileges for father or partner, siblings, and grandparents provide nurses with excellent opportunities to observe interactions and identify behavior that demonstrate positive or negative attachment. Attachment behaviors can be easily observed during infant feeding sessions. Box 20-1 presents guidelines for assessment of attachment behaviors. The labor process significantly affects the immediate attachment of mothers to their newborn infants. Factors such as a long labor, feeling tired or “drugged” after birth, problems with breastfeeding (Tharner, Luijk, Raat, et al., 2012), premature birth, and being separated from the infant at birth (Flacking, Lehtonen, Thomson, et al., 2012; Hoffenkamp, Tooten, Hall, et al., 2012) can delay the development of initial positive feelings toward the newborn. Referral to groups such as La Leche League International (www.llli.org) or Postpartum Support International (www.postpartum.net) can be useful. Early skin-to-skin contact between the mother and newborn immediately after birth and during the first hour facilitates maternal affectionate and attachment behaviors (Flacking, Lehtonen, Thomson, et al., 2012; Hung and Berg, 2011; Moore, Anderson, Bergman, et al., 2012). The newborn is placed in the prone position on the mother’s bare chest; the baby and mother’s chest are covered with a warm, dry blanket. This practice promotes early and effective breastfeeding and increases breastfeeding duration. It is also associated with less infant crying, improved thermoregulation (especially in low-birth-weight infants), and improved cardiorespiratory stability in late preterm infants (Moore, Anderson, Bergman, et al., 2012; Thukral, Sankar, Agarwal, et al., 2012). Extended contact with the infant should be available for all parents but especially for those at risk for parenting inadequacies, such as adolescents and low-income women. Postpartum nurses need to consider and encourage activities that optimize family-centered care (Welch, Hofer, Brunelli, et al., 2012). Baby Friendly status for a hospital is one means to promote family-centered care (Jaafar, Lee, and Ho, 2012; Perrine, Scanlon, Li, et al., 2012; Smith, Moore, and Peters, 2012; Vasquez and Berg, 2012). Touch, or the tactile sense, is used extensively by parents as a means of becoming acquainted with the newborn. Many mothers reach out for their infants as soon as they are born and the cord is cut. Mothers lift their infants to their breasts, enfold them in their arms, and cradle them. Once the infant is close, the mother begins the exploration process with her fingertips, one of the most touch-sensitive areas of the body. Within a short time, she uses her palm to caress the baby’s trunk and eventually enfolds the infant. Gentle stroking motions are used to soothe and quiet the infant; patting or gently rubbing the infant’s back is a comfort after feedings. Infants also pat the mother’s breast as they nurse. Both seem to enjoy sharing each other’s body warmth. Parents seem to have an innate desire to touch, pick up, and hold the infant (Fig. 20-4). They comment on the softness of the baby’s skin and note details of the baby’s appearance. As parents become increasingly sensitive to the infant’s like or dislike of different types of touch, they draw closer to the baby. Touching behaviors of mothers vary in different cultural groups. For example, minimal touching and cuddling is a traditional Southeast Asian practice thought to protect the infant from evil spirits. Because of tradition and spiritual beliefs, women in India and Bali have practiced infant massage since ancient times (Waugh, 2011). Parents repeatedly demonstrate interest in having eye contact with the baby. Some mothers remark that once their babies have looked at them, they feel much closer to them. Parents spend much time getting their babies to open their eyes and look at them. In North American culture, eye contact appears to reinforce the development of a trusting relationship and is an important factor in human relationships at all ages. In other cultures, eye contact is perceived differently (see Cultural Competence box). For example, in Mexican culture, sustained direct eye contact is considered to be rude, immodest, and dangerous for some. This danger may arise from the mal de ojo (evil eye), resulting from excessive admiration. Women and children are thought to be more susceptible to the mal de ojo (D’Avanzo, 2008). As newborns become functionally able to sustain eye contact with their parents, they spend time in mutual gazing, often in the en face position. In this position, the parent’s face and the infant’s face are approximately 8 inches apart and on the same plane (see Fig. 20-2). Nurses and nurse-midwives/physicians can facilitate eye contact immediately after birth by positioning the infant on the mother’s abdomen or breasts with the mother’s and the infant’s faces on the same plane. Dimming the lights encourages the infant’s eyes to open. To promote eye contact, instillation of prophylactic antibiotic ointment into the infant’s eyes can be delayed until the infant and parents have had some time together in the first hour after birth. The fetus is in tune with the mother’s natural rhythms, biorhythmicity, such as her heartbeat. After birth, the mother’s heartbeat or a recording of a heartbeat can sooth a crying infant. One task of a newborn is to establish a personal biorhythm. Parents can help in this process by giving consistent loving care and by using their infant’s alert state to develop responsive behavior and increase social interactions and opportunities for learning (Fig. 20-5). The more quickly parents become competent in child care activities, the more quickly they can direct their psychologic energy toward observing the communication cues the infant gives them. Synchrony refers to the “fit” between the infant’s cues and the parent’s response. When parent and infant have a synchronous interaction, it is mutually rewarding (Fig. 20-6). Parents need time to learn to interpret the infant’s cues correctly. For example, the infant develops a specific cry in response to different situations such as boredom, loneliness, hunger, and discomfort. The parent may need assistance in interpreting these cries, along with trial-and-error interventions, before synchrony develops. Rubin (1961) identified three phases of maternal role attainment in which the mother adjusts to her parental role. These phases extend over the first several weeks and are characterized by dependent behavior, dependent-independent behavior, and interdependent behavior (Table 20-4). Rubin’s research was conducted when the length of stay in the hospital was for a longer period (3 to 5 or more days). With today’s early discharge, women seem to move through the phases faster. TABLE 20-4 Phases of Maternal Postpartum Adjustment Date from Rubin R: Basic maternal behavior, Nurs Outlook 9(11):683–686, 1961. Mercer (2004) suggested that the concept of maternal role attainment be replaced with becoming a mother to signify the transformation and growth of the mother’s identity. Becoming a mother implies more than attaining a role. It includes learning new skills and increasing her confidence in herself as she meets new challenges in caring for her child or children. Mercer (2004) identified four stages in the process of becoming a mother (Mercer and Walker, 2006, pp. 568-569): (a) commitment, attachment to the unborn baby, and preparation for delivery and motherhood during pregnancy (b) acquaintance/attachment to the infant, learning to care for the infant, and physical restoration during the first 2 to 6 weeks following birth (c) moving toward a new normal (d) achievement of a maternal identity through redefining self to incorporate motherhood (around 4 months)

Transition to Parenthood

Parental Attachment, Bonding, and Acquaintance

FACILITATING BEHAVIORS

INHIBITING BEHAVIORS

Visually alert; eye-to-eye contact; tracking or following of parent’s face

Sleepy; eyes closed most of the time; gaze aversion

Appealing facial appearance; randomness of body movements reflecting helplessness

Resemblance to person parent dislikes; hyperirritability or jerky body movements when touched

Smiles

Bland facial expression; infrequent smiles

Vocalization; crying only when hungry or wet

Crying for hours on end; colicky

Grasp reflex

Exaggerated motor reflex

Anticipatory approach behaviors for feedings; sucks well; feeds easily

Feeds poorly; regurgitates; vomits often

Enjoys being cuddled and held

Resists holding and cuddling by crying, stiffening body

Easily consolable

Inconsolable; unresponsive to parenting, caregiving tasks

Activity and regularity somewhat predictable

Unpredictable feeding and sleeping schedule

Attention span sufficient to focus on parents

Inability to attend to parent’s face or offered stimulation

Differential crying, smiling, and vocalizing; recognizes and prefers parents

Shows no preference for parents over others

Approaches through locomotion

Unresponsive to parent’s approaches

Clings to parent; puts arms around parent’s neck

Seeks attention from any adult in room

Lifts arms to parents’ in greeting

Ignores parents

FACILITATING BEHAVIORS

INHIBITING BEHAVIORS

Looks; gazes; takes in physical characteristics of infant; assumes en face position; eye contact

Turns away from infant; ignores infant’s presence

Hovers; maintains proximity; directs attention to, points to infant

Avoids infant; does not seek proximity; refuses to hold infant when given opportunity

Identifies infant as unique individual

Identifies infant with someone parent dislikes; fails to recognize any of infant’s unique features

Claims infant as family member; names infant

Fails to place infant in family context or identify infant with family member; has difficulty naming

Touches; progresses from fingertip to fingers to palms to encompassing contact

Fails to move from fingertip touch to palmar contact and holding

Smiles at infant

Maintains bland countenance or frowns at infant

Talks to, coos, or sings to infant

Wakes infant when infant is sleeping; handles roughly; hurries feeding by moving nipple continuously

Expresses pride in infant

Expresses disappointment, displeasure in infant

Relates infant’s behavior to familiar events

Does not incorporate infant into life

Assigns meaning to infant’s actions and sensitively interprets infant’s needs

Makes no effort to interpret infant’s actions or needs

Views infant’s behaviors and appearance in positive light

Views infant’s behavior as exploiting, deliberately uncooperative; views appearance as distasteful, ugly

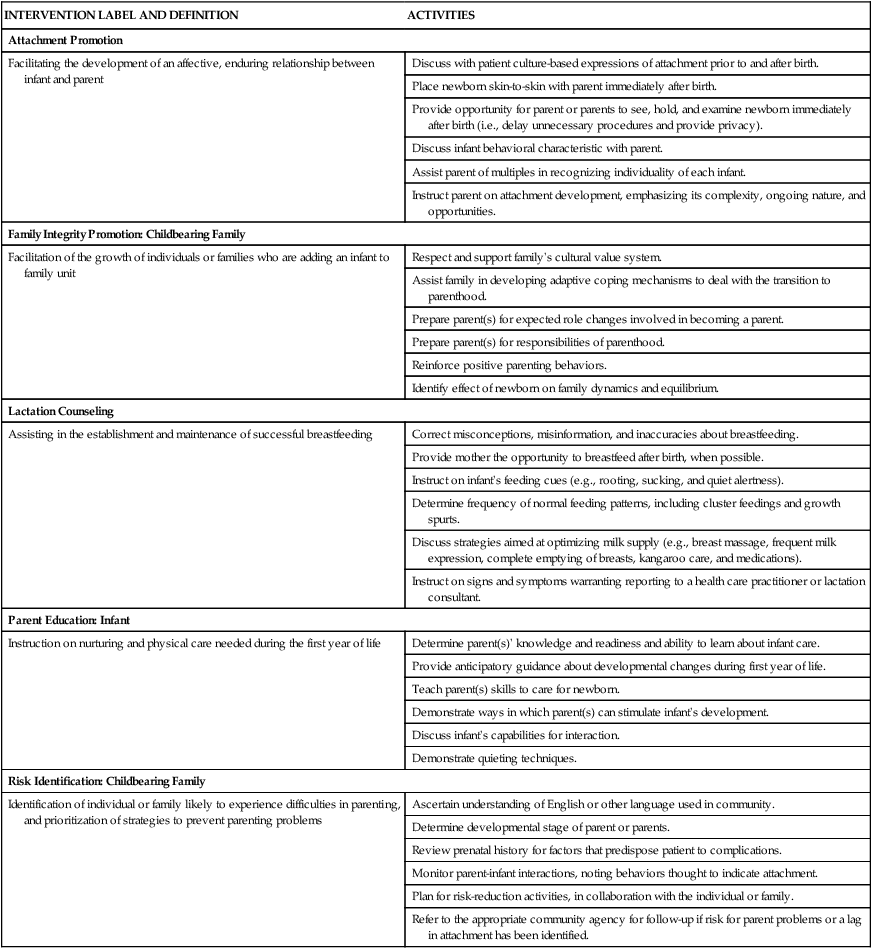

INTERVENTION LABEL AND DEFINITION

ACTIVITIES

Attachment Promotion

Facilitating the development of an affective, enduring relationship between infant and parent

Discuss with patient culture-based expressions of attachment prior to and after birth.

Place newborn skin-to-skin with parent immediately after birth.

Provide opportunity for parent or parents to see, hold, and examine newborn immediately after birth (i.e., delay unnecessary procedures and provide privacy).

Discuss infant behavioral characteristic with parent.

Assist parent of multiples in recognizing individuality of each infant.

Instruct parent on attachment development, emphasizing its complexity, ongoing nature, and opportunities.

Family Integrity Promotion: Childbearing Family

Facilitation of the growth of individuals or families who are adding an infant to family unit

Respect and support family’s cultural value system.

Assist family in developing adaptive coping mechanisms to deal with the transition to parenthood.

Prepare parent(s) for expected role changes involved in becoming a parent.

Prepare parent(s) for responsibilities of parenthood.

Reinforce positive parenting behaviors.

Identify effect of newborn on family dynamics and equilibrium.

Lactation Counseling

Assisting in the establishment and maintenance of successful breastfeeding

Correct misconceptions, misinformation, and inaccuracies about breastfeeding.

Provide mother the opportunity to breastfeed after birth, when possible.

Instruct on infant’s feeding cues (e.g., rooting, sucking, and quiet alertness).

Determine frequency of normal feeding patterns, including cluster feedings and growth spurts.

Discuss strategies aimed at optimizing milk supply (e.g., breast massage, frequent milk expression, complete emptying of breasts, kangaroo care, and medications).

Instruct on signs and symptoms warranting reporting to a health care practitioner or lactation consultant.

Parent Education: Infant

Instruction on nurturing and physical care needed during the first year of life

Determine parent(s)’ knowledge and readiness and ability to learn about infant care.

Provide anticipatory guidance about developmental changes during first year of life.

Teach parent(s) skills to care for newborn.

Demonstrate ways in which parent(s) can stimulate infant’s development.

Discuss infant’s capabilities for interaction.

Demonstrate quieting techniques.

Risk Identification: Childbearing Family

Identification of individual or family likely to experience difficulties in parenting, and prioritization of strategies to prevent parenting problems

Ascertain understanding of English or other language used in community.

Determine developmental stage of parent or parents.

Review prenatal history for factors that predispose patient to complications.

Monitor parent-infant interactions, noting behaviors thought to indicate attachment.

Plan for risk-reduction activities, in collaboration with the individual or family.

Refer to the appropriate community agency for follow-up if risk for parent problems or a lag in attachment has been identified.

Assessment of Attachment Behaviors

Parent-Infant Contact

Early Contact

Extended Contact

Communication between Parent and Infant

The Senses

Touch

Eye Contact

Biorhythmicity

Reciprocity and Synchrony

Parental Role After Birth

Becoming a Mother

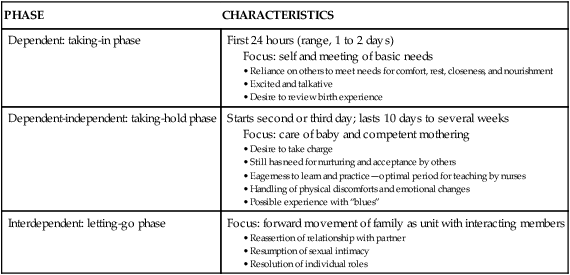

PHASE

CHARACTERISTICS

Dependent: taking-in phase

First 24 hours (range, 1 to 2 days)

Focus: self and meeting of basic needs

Dependent-independent: taking-hold phase

Starts second or third day; lasts 10 days to several weeks

Focus: care of baby and competent mothering

Interdependent: letting-go phase

Focus: forward movement of family as unit with interacting members

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Transition to Parenthood

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access