However, the logistical difficulties of setting up a pPCI service mean that roll-out of pPCI at a national level is gradual, and while significant numbers of patients are now treated with pPCI, the Department of Health (2008) acknowledged that roll-out of a national service in the UK would take time, with full implementation anticipated by 2011, and while implementation in some areas outside the UK is complete, in other areas access to pPCI continues to develop at a lesser rate.

Without question, the time taken to treatment for STEMI greatly influences outcome and with the advent of pPCI this is equally relevant. The time measure “call to balloon” (CTB) is a measure of likely treatment efficacy, with the greater mortality benefits seen with low CTB times at 30 days, one year and 18 months following intervention. For this reason CTB times are monitored at a national level in the UK with a recommended CTB time of no more than 120 minutes considered acceptable. Close collaboration is required between acute services, treatment centres and ambulance services to develop pathways that support immediate patient transfer, often across county or health authority boundaries, to heart attack centres for timely treatment, and for this reason the skill of the ambulance crew is paramount in identifying the patient with STEMI and transferring them directly to a heart attack centre. It does not help the patient to delay transfer by calling at a centre that cannot offer pPCI facilities in order to confirm the diagnosis, and while there can be understandable nervousness about patient stability en route, it should be noted that data supporting the benefits of pPCI came from studies that included people who were sick or unstable during transfer.

pPCI has dramatically changed the role of the coronary care unit (CCU) nurse and if the patient is admitted to a CCU in advance of pPCI, the focus of the nurse is on maintaining patient safety, nursing measures to reduce myocardial oxygen demand and increase myocardial oxygen supply, maintenance of adequate pain relief and management of early arrhythmias (see Chapter 10), along with preparation of the patient for intervention, including consent. A high loading dose (600 mg) of clopidogrel may have been given pre-hospital, but if not, the nurse should administer this without delay, and again this single loading dose can be given either with a prescription or using a PGD. Similarly, according to local protocol prasugrel may be used as an alternative with a loading dose of 60 mg (see above).

As pPCI services develop, so does the means by which patients are delivered to heart attack centres for intervention, including direct ambulance transfer to angiography facilities in tertiary centres to expedite treatment, and the patient may not be admitted to a CCU until after the procedure (see Appendix A for more details on safe patient transfer). Priorities in this case are initial rest and monitoring for complications of the procedure, including bleeding at the arterial access site, early stent thrombosis manifest as further chest pain with ST elevation, and the risk of early arrhythmias (see Chapter 10). Complications following the initial treatment phase remain and are directly related to the location and extent of myocardial damage. For this reason an echocardiogram to assess the extent of damage to the myocardium is invaluable, and in addition it facilitates the detection of other potential complications, such as thrombus in the left ventricle.

The majority of patients recover rapidly following pPCI and need careful management and early assessment by a cardiac rehabilitation specialist to establish a plan for early, medium- and long-term recovery. Medical therapy will include pharmacological secondary prevention, but because patients recover following pPCI there is a significant reduction in hospital stay compared with treatment with thrombolysis.

Thrombolysis

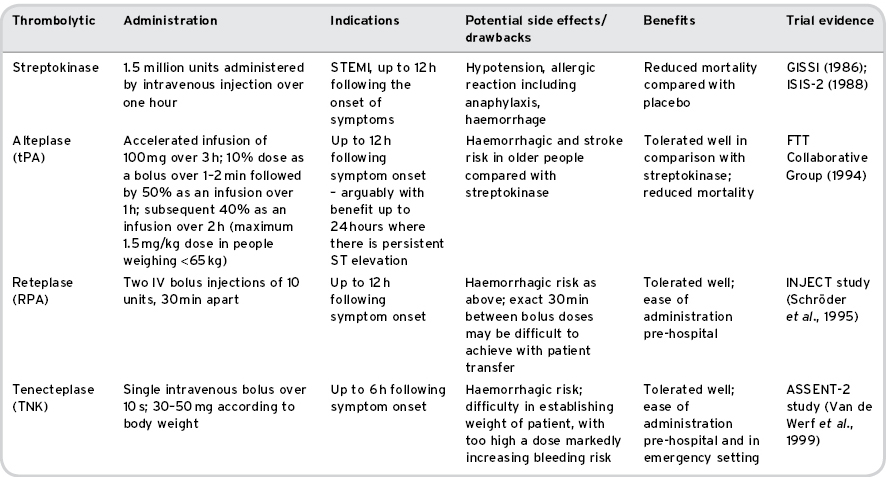

Thrombolytic therapy reduces mortality from MI, certainly up to 12 hours and possibly longer from the onset of symptoms (Grahame-Smith and Aronson, 2002). Streptokinase, alteplase, anistreplase and urokinase are all activators of plasminogen and thus cause fibrinolysis; they are summarised in Table 8.1.

Table 8.1 Thrombolytic therapies in current UK use

Administration of Thrombolysis

Thrombolytic therapies, as described above, can be administered in the pre-hospital setting or when the patient arrives in hospital. In the setting of ACS, thrombolysis is indicated only for patients presenting with ECG criteria suggesting STEMI along with a clinical presentation consistent with acute MI. Thrombolytics increase the risk of bleeding and have also been demonstrated to increase the risk of stroke. While this risk is outweighed by the benefits of improved survival following STEMI, some patients remain unsuitable for thrombolysis, for instance because they are at higher risk of bleeding (DH, 2008).

Whoever initiates thrombolytic therapy must establish whether there is any contra-indication or caution to its administration (see Box 8.2) before initiating treatment. If a thrombolytic has not been administered by a paramedic, in many areas of the UK nurses are able to administer thrombolysis either following a prescription or using a PGD, which allows a nurse to supply and administer a single dose of medication without a prescription under specific circumstances (Humphreys and Smallwood, 2004). In addition, the advent of non-medical prescribing has in some areas facilitated better access to timely treatment without the need for extensive protocols in this group of patients, and without need for early attendance by medical staff.

Box 8.2 Contraindications to thrombolysis

- Recent (<6 weeks): major trauma, surgery, dental extraction, menorrhagia, post partum

- Prolonged (>20 min) CPR

- Cerebrovascular accident within 6 months, or any haemorrhagic CVA or CVA of unknown aetiology

- Coma

- Bleeding diathesis

- Patients taking warfarin

- Severe liver disease

- Severe hypertension (BP > 180/100 despite treatment)

- Recent peptic ulcer symptoms

- Acute pancreatitis

- Oesophageal varices

- Pulmonary disease with cavitation

- Pregnancy

- Laser therapy for retinopathy in the last week

- Infective endocarditis

- Pericarditis

- History suggestive of aortic dissection

- Known aortic aneurysm

- Patients who have had more than 12 h of chest pain

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree