The United States Health Care System

Frances A. Maurer

Focus Questions

What are the basic features and components of the U.S. health care system?

What distinguishes the U.S. health care system from those of other developed countries?

Why do community/public health nurses need to understand the health care system?

What are the two competing foci of care? Is one focus of care more prevalent today?

How is the private sector of health care delivery organized?

What type of private-sector organization is the major provider of health care services?

What are the major problems with the current health care delivery system?

How have problem-solving strategies impacted health care services, personnel, and costs?

What are the significant changes in health care delivery in the past decade and today?

What are some of the ongoing and new proposals for health care reform?

Key Terms

Decentralization

Direct care providers

Direct care services

Free market

Gross domestic product (GDP)

Health care system

Home care

Indirect care services

Out-of-pocket expenses

Primary prevention

Private sector

Public sector

Secondary prevention

Tertiary prevention

Third-party reimbursement

Universal coverage

Vested interests

Wellness centers

The United States is in the midst of dramatic changes in the organizational structure and delivery of health care. Mergers and acquisitions have consolidated medical service providers into fewer, but larger, corporate models (Harrington, 2011). Managed care has become a popular form of health care delivery service. Technology has expanded the boundaries of treatment for difficult medical conditions and increased the costs of treatments. State and federal budgets crises are forcing reductions in government support for health care services, at a time when the number of people without health insurance continues to climb. Quality-of-care issues are a rising public concern. The costs of care, the problems of access to care, and the increasing concerns over the quality of health care have renewed the debate over the question whether this country should adopt some form of national health coverage for all citizens.

In 1994, President Bill Clinton attempted national health care reform. Although there was popular support for change, there was also vigorous opposition. A significant public relations campaign led by health industry providers such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs), hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and other health-related businesses was successful in defeating the initiative (Gold, 1999; Navarro, 1995). Ironically, since then, there has been a substantial shift toward managed health care, one of the principal recommendations of President Clinton’s Task Force (White House Domestic Policy Council, 1993). The main difference is in oversight responsibilities. The Clinton Task Force envisioned oversight as a public-sector function, but today, it remains primarily a private-sector corporate responsibility. More recently, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, commonly called the Affordable Care Act, has proposed incremental changes to services, public oversight, and increased emphasis on prevention in health care delivery in the United States. Although the law has been enacted and some changes have already occurred, vigorous opposition to the law has resulted in court challenges. In June 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the law. Today, the U.S. health care delivery system remains a system in transition. Public concerns about access and quality of care have produced piecemeal legislative attempts to protect consumers’ rights and improve health services, evoking opposition from vested interests and persons with a different philosophy of health care delivery and systems organization.

A health care system is the organizational structure in which health care is delivered to a population. What kind of health care system does the United States have? What are its component parts? This chapter examines the current structure and principal areas of concern of the U.S. health care system. At the end of the chapter, potential directions for further change are explored.

Few people really stop to think about the health care system and the organizational structure that delivers care until they have an unsatisfactory personal experience with the system. Consumer and health professional dissatisfaction is building, leading to critical questions about the current system, identification of areas for change, and suggestions about how the system might be changed.

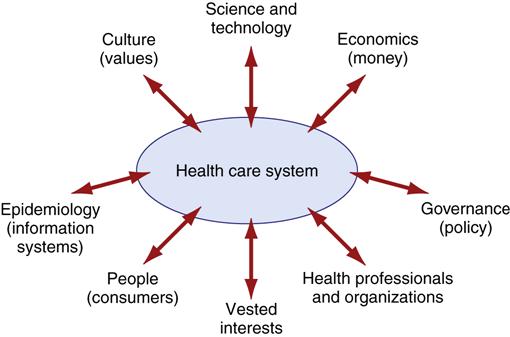

Most Americans, including most health care professionals, have tended to view the health care system as inflexible and unchangeable. The system is, in fact, responsive to outside influence (Figure 3-1). Changes and modifications do occur, albeit slowly and incrementally because the system is so large. For example, the role of nurse practitioners was gradually expanded over a long period. Discontent periodically builds to such a peak that significant change occurs in a relatively short time. For example, dissatisfaction with the financial burdens and limited access to medical care for older Americans led to the enactment of the Medicare program in 1965. Concern over health care costs in the 1990s led to an increasing reliance on managed care organizations as health care providers. Currently, the country is again experiencing dissatisfaction with health care delivery (Mechanic, 2008; Patel & Rushefsky, 2006; Shi, Singh, & Tsai, 2010.).

Primary prevention, the promotion of healthy behaviors and reduction of health risks, has once again become a popular concept. Former Congressman Newt Gingrich (2002), who helped defeat the Clinton health care plan, is now espousing a more preventive, consumer-focused delivery system. President George W. Bush and the U.S. Congress passed a prescription drug plan for Medicare recipients. Most recently, the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act is intended to increase the number of persons covered by some type of health insurance, increase the accountability of providers, and improve the quality of health care services. Once again, there exists a window of opportunity for health care change.

Health care professionals bear a responsibility to know and understand the system in which they function because it has considerable impact on both their behaviors and the health behaviors of the people they serve. Nurses should be cognizant of the issues that affect their nursing practice both in the workplace and in the broader context of the entire health care system. Beyond its influence on their personal nursing practice, community health nurses must understand the impact of the system on individual clients, groups, and communities.

Currently, health care is neither available nor accessible to everyone. Millions lack health insurance and are unable to pay for basic services. Every day, community health nurses see people who are denied basic services and others with serious illnesses delaying treatment because of cost concerns. Because the professional practice of nursing is built around the promotion of health, the prevention of illness, and the restoration of health to all in need, it is hard for community health nurses to see people in need and know that, for some, they can offer no solution to the difficulties in accessing health care.

Ultimately, the real impact of any health care system must be measured in terms of the people it serves: How healthy is our population? How does our health status compare with that of other nations? Does our health care system prevent premature death and disability and provide good care to most of its citizens? Nurses need basic information about the health care system so that they can make informed judgments about the efficacy of the current system and the impact of suggested reforms.

Our traditional health care system

When compared with health care systems in other developed countries, the delivery network in the United States seems disorganized and confusing (Sultz & Young, 2011). The U.S. health care system has been defined as “a system without a system,” “a fragmented system,” and “a nonsystem” (Geyman, 2008; Harrington & Estes, 2008; Shi & Singh, & Tsai, 2010). There is no central organization that plans and links the various elements into an integrated and purposeful whole. Some argue that as disjointed and decentralized as it might be, it is still a system—a system that continues to evolve in response to societal and market pressures (Patel & Rushefsky, 2006).

Key Features of the U.S. Health Care System

Three prominent features of the U.S. health care system help explain, to some degree, the structure of the system and the manner in which it evolved. These features include highly decentralized governance, a strong emphasis on a laissez-faire philosophy, and an abundance of economic resources.

Decentralization

Consistent with other aspects of governance in the United States, legal governance and regulation of the health care delivery system are highly decentralized. The U.S. government was designed by individuals whose previous experiences led them to mistrust a highly centralized, autocratic system. Their solution was a decentralized federated system with checks and balances at each level. With decentralization, local communities, the states, and the federal government all share the responsibilities for the regulation and provision of services to the population; health care services are no exception. The United States has a delivery system in which funding, planning, regulation, and service delivery are influenced by city, county, state, and federal government policies, as well as by the policies of nongovernmental organizations such as businesses.

Laissez-Faire Philosophy

The free market economy of the United States encourages a laissez-faire approach. There is no centralized planning structure. In a free market, private enterprise is allowed to develop goods and services as it chooses and to offer them to the clientele, or market, it selects. In the health care service market, private individuals, groups, or corporations can plan, offer, and deliver health care to the target groups they wish to serve. Hospital owners or managers, physicians, and philanthropists, not government, determine the organizational structure of the U.S. health care system. As with any business operation, payment is expected for service provided. In this country, a portion of the population cannot pay for service. For those unable to pay, the question whether health care is a right or a privilege becomes critical. Debate on this question has raged since the nation’s inception (Feldstein, 2012; Gebbie, 2007; Lindblom, 1953; Marshall, 2011; Papadimos, 2007; Reinhardt, 2009; Wilensky, 1975). Those who espouse a totally free market system support a laissez-faire attitude toward health care services. They consider health care a privilege, rather than a right, and would not support government intervention to ensure health care for those who cannot pay. Those who consider health care a right, rather than a privilege, would support action aimed at providing health care services to all.

In this country, health care is provided to the population by a combination of private and public means. Our leaning toward a free market economy has encouraged the development of a private, entrepreneurial delivery system and personal responsibility for medical expenses (Sultz & Young, 2011). This private subsystem serves middle- and upper-income Americans who can afford to pay for their care.

Public concerns, however, do not allow a totally laissez-faire approach. Most Americans (65%) support the idea of basic health care services for all (Pew Research Center, 2009). The public health community’s commitment to the ethical position of providing the greatest good for the greatest number supports universal access to care rather than the laissez-faire approach. Government has gradually undertaken to provide some support to those persons who cannot afford to pay for health care. The public subsystem tends to care primarily for the poor and special populations.

Abundant Resources

Although the United States is a wealthy country, its economic resources for health care are limited. However, it spends more on health, in actual dollars, than do most other countries. In 2009, health care expenditures were $2.5 trillion, or 17.6% of the gross domestic product (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011c). The United States has devoted large sums of money to research and has led the way in the development and use of complex and expensive medical procedures and equipment, for example, organ transplantation, in vitro fertilization, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Decentralized governance, mass expenditures, and a free market philosophy have helped shape the existing health care system. As various aspects of the system are examined in this chapter, it would be useful to attempt to identify how each of these elements has an impact on a particular area of practice or delivery of care to population subgroups.

Distinctions from Other Health Care Systems

Most developed countries have national health care programs administered by their governments. The U.S. health care system is unique. It has neither a national health care plan nor a central administration to deliver health care to its people (Patel & Rushefsky, 2006; Shi, Singh & Tsai, 2010; Kover & Knickman, 2011). In Chapter 5, various health care models used by other developed countries are discussed.

Health Planning

Countries with national health care systems engage in more comprehensive health care planning. Central planning is possible because government has the means to influence services either by providing direct care or by reimbursing the cost of care for most of its citizens.

In contrast, the United States has engaged in little central health planning, although the federal government is becoming more involved in national health planning and has established national health objectives. These objectives are only guidelines and do not have the force of law. Currently, those segments of the health care system not directly under federal control are free to ignore or meet the objectives as they choose.

Health Insurance and Health Status

The most frequent criticism of our health care system is that delivery of “basic” (primary and preventive care) services is not readily available to the entire population (McKinsey and Company, 2007; Sultz & Young, 2011). Despite large health care expenditures, a significant segment of the population does not receive care. At least 59.1 million Americans have no health coverage (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report [MMWR], 2010). The U.S. government provides less public funding for health care than does any other developed country (Rodwin, 2005; Torrens, 2008). Most countries commit more public funds to provide more services while spending less of their gross domestic product (GDP) on health care services. GDP is a measure of all goods and services sold in the United States. Chapter 4 provides a more detailed discussion of health care spending and services in other countries.

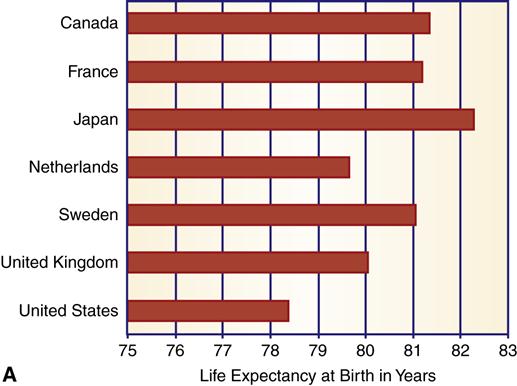

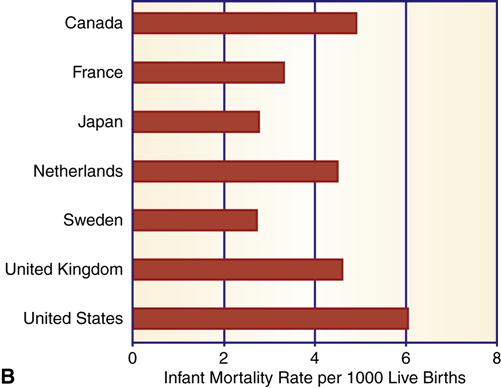

If the U.S. health care system provided a better standard of health compared with the systems of other countries, the differences in the expenditure of public funds would be more understandable. That is not the case, however. Comparison of infant mortality and life expectancy for eight selected countries indicates that the United States ranks lowest in life expectancy and highest in infant mortality (Figure 3-2). In fact, the United States ranks last among 19 industrialized nations in life expectancy and infant mortality (Central Intelligence Agency [CIA], 2011). In addition, the United States has a higher infant mortality rate than Andorra, Cuba, Malta, Slovenia, and South Korea.

Components of the U.S. health care system

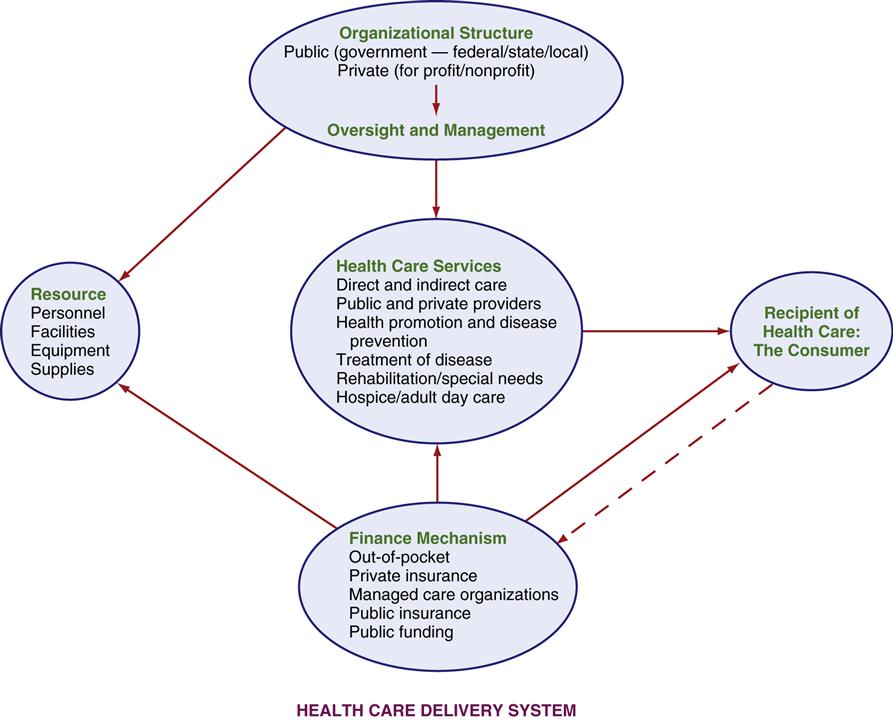

The U.S. health care system is complex, and it is difficult to reduce all of its elements, influences, and decision makers into a simple diagram. Figure 3-3 provides a basic model that identifies the essential components that form the basis of the U.S. health care system. The model illustrates some of the interrelationships. Each component is affected by, and has impact on, the others. Ultimately, the system does link the consumer to health care services.

Organizational Structure

In health care, structure significantly influences function. Structure determines how goods or resources are acquired and how services are distributed or provided. The organizational structure of the U.S. health care system is a disjointed combination of public and private agencies, including government (federal, state, county, city, and local) and voluntary, charitable, entrepreneurial, and professional agencies and organizations. All of these agencies are involved in decisions that have an impact on the delivery of health care. Agencies sometimes operate with competing or overlapping objectives and functions. Because of the absence of a central organization, gaps exist in services and in population groups served. (It is helpful to keep this concept in mind as the discussion continues.)

Management and Oversight

The three key features of our health care system were identified earlier. Two of these are important to the management aspect of health care. Both decentralized governance and a laissez-faire philosophy have created the environment within which oversight functions. A single overseer or manager is lacking, as is a central plan for organizing and delivering health care. Instead, multiple levels of government interrelate and interact with multiple levels of private-sector management in a bewildering arrangement. For example, in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), there is both federal and state funding and oversight. The health care services the children receive come from physicians, hospitals, managed care organizations, and other health care providers. Those providers, in turn, must conform to Medicaid and CHIP regulations and reviews.

Multiple Levels of Government

Within government itself, there are planning, legislative, and regulatory management efforts at the federal, state, county, and city levels. Each layer directs services within its scope of operation. Because of the decentralized nature of American government, federal agencies usually manage specific programs by delegating day-to-day administration and oversight to local authorities. However, the federal agencies devise guidelines or criteria that must be met by the specific program. For example, the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Program has multiple levels of managers and requirements. The WIC Program managers in the field, who actually provide services to target groups, must comply with criteria that have been set at the federal and state levels. The WIC Program field director (county, city, or geographical district operation) reports to the state agency responsible for the program. The state manager, in turn, reports to an official in the U.S. Department of Agriculture. That individual, in turn, answers to both the President (executive branch) and the Congress (legislative branch) to ensure that management directives and budgeting requirements are followed.

Variety of Private Management Styles

Management, planning, and oversight methods of private organizations vary widely. They include centralized and decentralized, democratic and autocratic, and laissez-faire and extremely regulated management efforts. Most private facilities operate with a board of directors that influences the planning and administrative processes.

Private facilities and organizations must comply with applicable federal, state, and local regulations, which place constraints on how they may operate, the types of services they may provide, and whether they may continue to offer services. State licensing is an example of regulatory activity. For instance, states conduct inspections and issue licenses for nursing homes and home care agencies. If the homes are not able to meet state standards, they are penalized through fines or are forced to close. Failure to meet licensing standards can also result in loss of revenue because some reimbursement mechanisms are tied to continued licensure.

Financing Mechanisms

The financing of health care services is discussed in detail in Chapter 4. In brief, financial support is derived from a variety of sources, both private and public (see Figure 3-3). Private sources include personal payments from individuals and families, private insurance payments, corporate payments, and charitable contributions. Public sources are composed of federal, state, and local government revenues directed toward health care services.

Resources

Health care resources are essential for the effective functioning of the health care system. These include (1) health care professionals, that is, personnel who run the system; (2) facilities such as hospitals and other structural elements from which care is provided; and (3) health care supplies and equipment. Because space is limited, only some of the relevant resources for health care delivery are highlighted in this chapter. Community health nurses need to know about health care resources, including the supply of other health care professionals, because resources influence the availability and accessibility of health care services to those in need.

Personnel

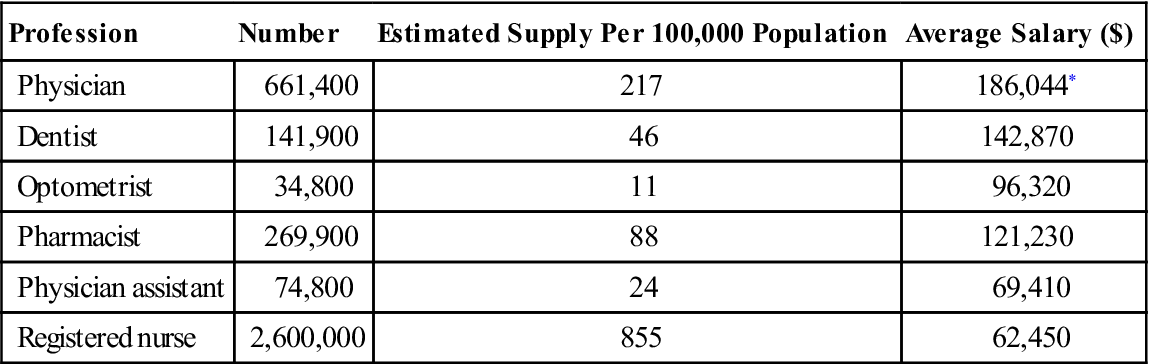

People are a crucial health care resource. Considerable variety in education, skill, and practice setting exists among health care professionals. Table 3-1 presents some of the most common health care professionals, their accessibility (supply), and their average salary levels.

Table 3-1

Comparisons of Selected Health Care Professions

| Profession | Number | Estimated Supply Per 100,000 Population | Average Salary ($) |

| Physician | 661,400 | 217 | 186,044* |

| Dentist | 141,900 | 46 | 142,870 |

| Optometrist | 34,800 | 11 | 96,320 |

| Pharmacist | 269,900 | 88 | 121,230 |

| Physician assistant | 74,800 | 24 | 69,410 |

| Registered nurse | 2,600,000 | 855 | 62,450 |

*Average salary for primary care physicians.

Data from U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011). Occupational outlook handbook: 2010-2011 edition. Washington, DC: Author.

Physicians

In the 1960s, both federal and state governments offered financial support to medical schools and eased certification requirements for foreign-trained physicians to increase the number of practicing physicians. These actions did increase the supply of physicians. Currently, there are 217 physicians per 100,000 population (estimate based on U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011a). The projected supply is not adequate to meet the needs of the population through 2025 (Health Resources and Service Administration [HRSA], 2007; Alliance for Health Reform, 2011).

The reasons for the expected physician shortage include an aging physician work force, geographical maldistribution of physicians, specialization, and an increased demand as a result of the Affordable Care Act. Health care reform will attempt to expand coverage to 32 million uninsured Americans. Physicians tend to concentrate in urban areas rather than in rural areas. New England and the mid-Atlantic states have the highest ratios of physicians to population, and the South Central and Mountain states have the lowest. The shortage of primary care physicians is, in part, the result of higher wages for doctors who choose to specialize (Alliance for Health Reform, 2011). Most physicians (about 76%) specialize; only 12.4% are engaged in primary care practice (American Medical Association, 2009). In contrast, other developed countries restrict specialty practice, and 50% to 70% of physicians are engaged in primary care. Only a few American physicians specialize in community health medicine.

Registered Nurses

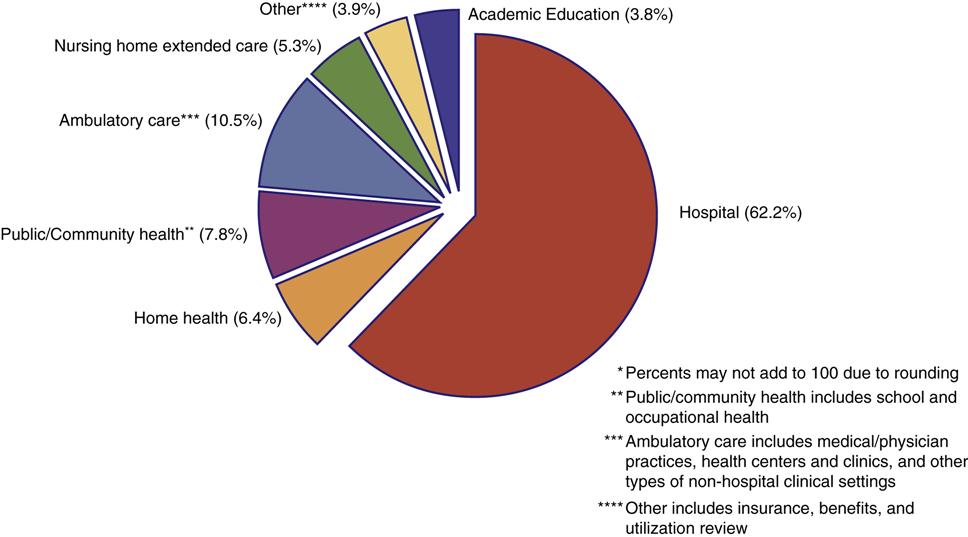

Registered nurses constitute the largest group of health care professionals. There are 2.6 million licensed registered nurses in the United States (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011a). Most are salaried employees. Hospitals remain their largest single employer, although hospital-based nurse employment continues to decline (Figure 3-4). Government data are not current for all sources of nurse employment. Figure 3-4 represents employment areas found in a 2008 sample survey. Community-based employment opportunities for registered nurses continue to expand, although the proportion practicing in community/public health has declined (see Chapter 1). Approximately 8% of registered nurses practice some form of community health nursing. Another 11% work at ambulatory care facilities that offer some community-related services.

Federal government estimates project a decline in the proportion of registered nurses practicing in hospital settings and an increased need for registered nurses prepared in community-type practice, including public health and ambulatory care. If health care reform initiatives continue to stress community- and home-based care, the need for community-based nursing services will create additional demand.

There have been cyclical shortages in the supply of registered nurses, but there is serious concern that the current shortfall may be more protracted and difficult to remedy (Unruh & Fottler, 2008). In the past, shortages have been alleviated by a combination of increase in salaries and increased enrollment of students in nursing programs. Today, enrollment in nursing programs is not expanding to meet the growing need. This is coupled with an aging registered nurse workforce. The average age of registered nurses in the workforce is 46 years (HRSA, 2010). These two factors may increase the length and severity of the current shortage period.

Nonphysician Practitioners/Extenders

Nonphysician practitioners/extenders are professionals who are trained to provide primary care in place of physicians and are either physician’s assistants or advanced nurse practitioners. Physician’s assistants are usually nonnurses with advanced education and certification.

Advanced nurse practitioners include nurse anesthetists, nurse clinical specialists, nurse practitioners, and nurse midwives. In most states, the Nurse Practice Act allows independent practice and direct reimbursement for nurse practitioners and nurse midwives, although some limitations persist (Fairman et al, 2011; Lugo et al, 2007). Of the approximately 233, 148 physician extenders, approximately 68% are nurse practitioners (HRSA, 2010; U.S. Department of Labor, 2011a). Many nonphysician practitioners serve populations that do not attract physicians, especially the poor and chronically ill (Brewer, 2005; Sultz & Young, 2011). Advanced nurse practitioners are especially good at working with the chronically ill because of their background in health teaching and their interest in health promotion and health maintenance. Nurse practitioners and nurse midwives are commonly employed in community health centers and other community agencies. Studies indicate that physician extenders compare favorably with physicians in the quality of care delivered and patient satisfaction with service (see Chapter 4).

Other Professionals

The supply of dentists, pharmacists, and optometrists is sufficient to meet the demand into the future. Most do not work in public health. Dental care is expensive; as a result, the poor and the uninsured frequently do not receive dental care. If dental care were to become part of the Medicare/Medicaid programs, then the demand for dentists would outstrip the current supply. The demand for optometrists is expected to grow because of the needs of aging baby boomers.

Allied Health Professionals

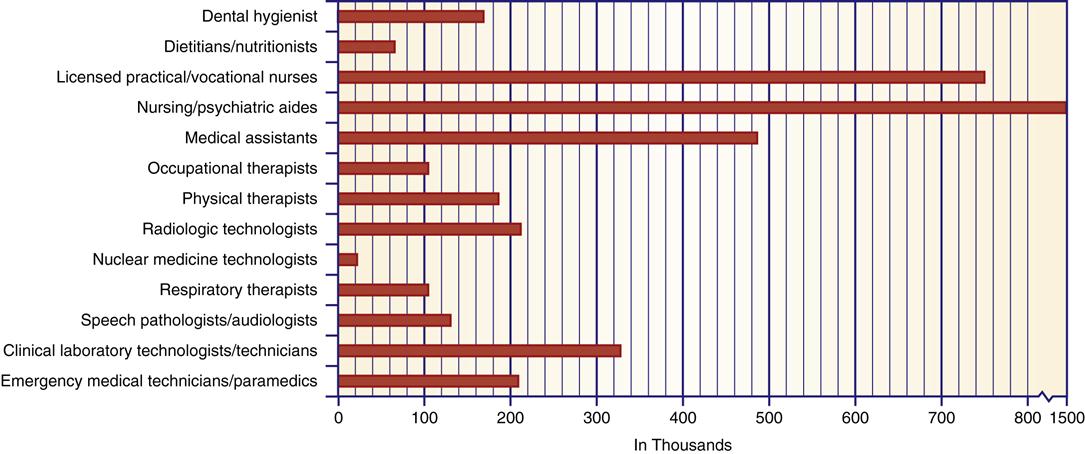

During the past several decades, a variety of new health care workers have emerged to assist the more established professional groups in providing care to the population. A list of selected allied health workers, with the approximate numbers in each category, is given in Figure 3-5. Their specialized occupational activities are wide ranging. The allied health worker most often involved in substantial direct client care is the licensed practical nurse (LPN) or licensed vocational nurse. Historically, the practical nurses assisted registered nurses, but licensed vocational and practical nurses have assumed responsibilities once thought to be the sole domain of professional nurses. In some states and clinical situations, LPNs administer medications, manage units, and take verbal orders from physicians. LPNs have limited experience in public health settings, although they are employed in ambulatory care and home health agencies.

Nursing aides provide personal care services in a variety of settings. They work under the direct supervision of registered nurses or LPNs. Some aides are certified through a formal education process, but many receive only informal instruction on the job. Nursing aides are poorly paid, which makes it difficult for agencies to retain competent, reliable employees.

Facilities

Health care is provided in a wide variety of inpatient and outpatient facilities. Some of these are listed in Box 3-1. The types of care delivered in facilities can be limited or wide ranging, simple or complex, and tailored to specific conditions or to a broad span of health concerns.

Box 3-2 outlines pertinent information about and services provided by selected health care facilities. There are 5795 hospitals in the United States. Approximately 86% of these are short-stay general hospitals (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, Table 172). More than 80% of U.S. hospitals are nonprofit or government owned. Nursing homes are the fastest growing segment of this market. Earlier hospital discharges and an ever-increasing population of older adults are the reasons for rapid growth of nursing homes. There are 15,700 nursing homes, three times the number of acute care hospitals (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, Table 194).

Before 1960, mental care/psychiatric hospitals were separate facilities operated primarily by state and local governments. Starting in the 1960s, efforts to provide persons with psychiatric disorders with the least restrictive environment resulted in a large number of discharges from these institutions. Chapter 33 provides a more detailed discussion of the changes in mental health services. Deinstitutionalization has resulted in the closing of facilities, and/or reduced bed capacity.

Primary care in clinics has always been provided to serve poor populations, but it is now becoming popular with other consumer groups. The greatest number of new ambulatory care clinics have been set up to attract middle-class consumers rather than clients from low-income groups or those receiving public assistance. Consumers who find the clinics particularly attractive are those with no regular physician and want quick treatment for a specific complaint. Hospitals, health care corporations, or physicians in group partnership generally sponsor the new facilities.

Payment at the time of service is a common feature of the newer clinics. Many do not process insurance forms as direct payment. Consumers are usually expected to file health insurance and Medicare claims to receive reimbursement for out-of-pocket expenses (those expenses paid for directly by the consumer), which may be covered by their insurance carrier.

Wellness centers promote healthy behaviors and assist consumers in eliminating or reducing risky behaviors. Wellness centers (also known as health promotion centers) and alternative medicine services are geared toward niche markets, primarily middle-class and wealthy individuals who can afford to pay. Health insurance and employers pay for limited numbers of these services. Some examples of services paid for by insurance are employer-sponsored exercise programs, smoking cessation programs, and stress reduction programs. In the alternative medicine area, acupuncture is the most frequently covered service.

Home care, which is care of the client in his or her own home, has surged as the number of older adults grows. Home care is popular because it is cost efficient and often preferred to other types of care (see Chapter 4). Today, there are more than 10,581 home care and hospice agencies in the United States, serving over 7.2 million clients (National Association for Home Care and Hospice, 2010). Approximately 86% of hospices are independently run, and the remainder are operated by home health agencies, hospitals, or skilled nursing facilities.

Equipment and Supplies

Health equipment and supplies are another health resource. Materials used in the diagnosis and treatment of specific illnesses, prosthetic devices, eyeglasses, hearing aids, and drugs constitute just a partial list of the types of equipment in this category. The industry is enormous. For example, in 2009 the cost of durable medical equipment was $34.9 billion (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, Table 136).

Medications are the largest single category. Drugs are a multibillion-dollar industry. In 2009, $293.2 billion was spent on drugs and other nondurable medical supplies (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, Table 136). Approximately 75% of the drugs sold are prescription medications. Prescription drugs are protected by patent for 17 years. Drug companies derive greater profits from the sale of brand name (patent) drugs, so there is clear incentive to protect and maintain patent rights as long as possible. Most companies, although they could, do not manufacture generic versions of their own patent drugs until after the 17-year patent limit has expired.

Health Services

Perhaps what is more important than the system is the final product. What does the system provide for consumers (refer to Figure 3-3)? Torrens (2008) asserts that a complete and comprehensive health system should provide certain essential health care services including the following:

The U.S. health care system contains most of these elements. However, not every community or individual has easy access to all service elements, and health care services are not well integrated and coordinated. Critics contend that care and consumer needs do not match well. Care is often inappropriate, and services are unevenly and unequally distributed (Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System, 2006; Fiscella & Williams, 2008; Torrens, 2008; Sultz & Young, 2011).

Consumer

The consumer is the recipient of services delivered by the system. Ideally, services should be planned and implemented to benefit the client. It is the consumer who is most affected by the operational efficiency or inefficiency of health care delivery.

The consumer and the health care services should be the focus of the health care professions. The consumer is the most vulnerable component and is the most likely to be hurt by ineffective functioning of the system. For example, health care providers might relocate or refuse certain patients (Medicaid patients) to maintain their incomes or to increase their profit margins. The consumers left behind or denied care are not the primary focus in the provider’s decision process. Refer to the section in Chapter 4 on free market failure for a discussion on how the shortcomings of the system might have a negative impact on consumers.

Some critics suggest that client care is secondary to profit (Catholic, 2009; Cohen & Piotrowska-Haugstetter, 2007; Feldstein, 2012; Shi & Singh, 2011a). The health care system is a large business. Improving a population’s health is not always the focus when planning and providing services and selecting the consumer groups to whom services will be provided. Profits and services are competing goals. Health care professionals and management personnel often derive greater benefits than the consumer by way of generous salaries, benefits, stock profits, and professional prestige (Krauss, 1977; Patel & Rushefsky, 2006; Reinhardt, 2009; Smith-Dewey, 2010).

Direct and indirect services and providers

In any delivery system, there are direct and indirect services and direct and indirect providers. Direct care services are health services delivered to an individual. Physical therapy, nursing care, and doctors’ visits are examples of direct services. Direct services are provided in a variety of settings, including hospitals, public health clinics, and, in the case of home health, the client’s home itself. The personnel who provide these types of services are considered direct care providers. Most health care personnel in the United States are engaged in direct care.

Indirect care services are those health care services that are not personally received by the individual, although they influence health and welfare. Health planning by community agencies, monitoring and regulation of environmental hazards, and inspection of public-use facilities are examples of indirect health services. Health is certainly affected by pollution of food and water sources and by community planning decisions regulating the number of hospital beds or the type of equipment employed in these facilities. The difference is that many of us are not consciously aware of the indirect services and how they affect our health.

Public and private sectors

Direct health care services in the United States are delivered in a two-tiered system of public and private providers. The private sector is composed of private organizations, both for-profit businesses and nonprofit organizations. For the most part, private enterprise provides direct services of personal health care to Americans who can pay, either directly (out of pocket) or through third-party payers (private health insurance plans). Some of these providers, particularly hospitals managed by churches and other philanthropic endeavors, provide a certain number of services to community members who cannot pay.

The public sector consists of services provided by public funds and public organizations. Services are largely provided by some type of governmental agency. The public sector is concerned with both direct and indirect services. Involvement with direct services is an attempt to provide care for those who cannot pay and for certain other target groups for whom government is legally required, or feels compelled, to provide health care, for example, veterans and American Indians. The large numbers of indirect services that are within government’s purview exist because the private sector is not interested in providing them. Funding for public services comes from local governments and communities and state and federal agencies. Charitable organizations, although part of the private sector, might also provide limited public-sector services.

Public sector: government’s authority and role in health care

Each of the three levels of the U.S. government assumes some of the responsibilities for health care. Indirect services make up a major portion of services provided by government. In keeping with a free market economy, government usually does not attempt to provide services in areas in which private enterprise provides care satisfactorily.

Various levels of government ensure care for certain population groups not covered by private-sector services. State and local governments are more involved in direct care. Federal, state, and local governmental agencies are frequently involved in the administration of a single program or basic service such as the WIC Program or the CHIP, discussed earlier. How they are involved, or the exact role each agency plays, is generally the distinguishing element.

Federal Government

The authority for the federal government’s involvement is derived from the Constitution of the United States. Although it is not explicitly stated, federal authority is assumed from the charge to provide for the general welfare and from the federal role in the regulation of interstate commerce. The federal government has the power to collect and spend monies for general welfare and to regulate businesses and organizations that conduct operations in more than one state. The federal role in health care has expanded, although actual implementation of programs is commonly delegated to the states. Ultimately, the federal government is responsible for protecting the health of its population.

Although all three branches of government make health-related decisions, the President and his or her staff (executive branch) and Congress (legislative branch) make the major policy decisions. These two branches set the tone for delivery of health care. They dictate which groups will be served and the manner of service. Both branches are subject to political pressures that influence the decision-making process.

Once the policy is decided, federal agencies are responsible for oversight and implementation. These agencies regulate and interpret health care law, administer services mandated by law, and are responsible for the supervision of compliance with health laws and regulations. Federal agencies are primarily involved in indirect services.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

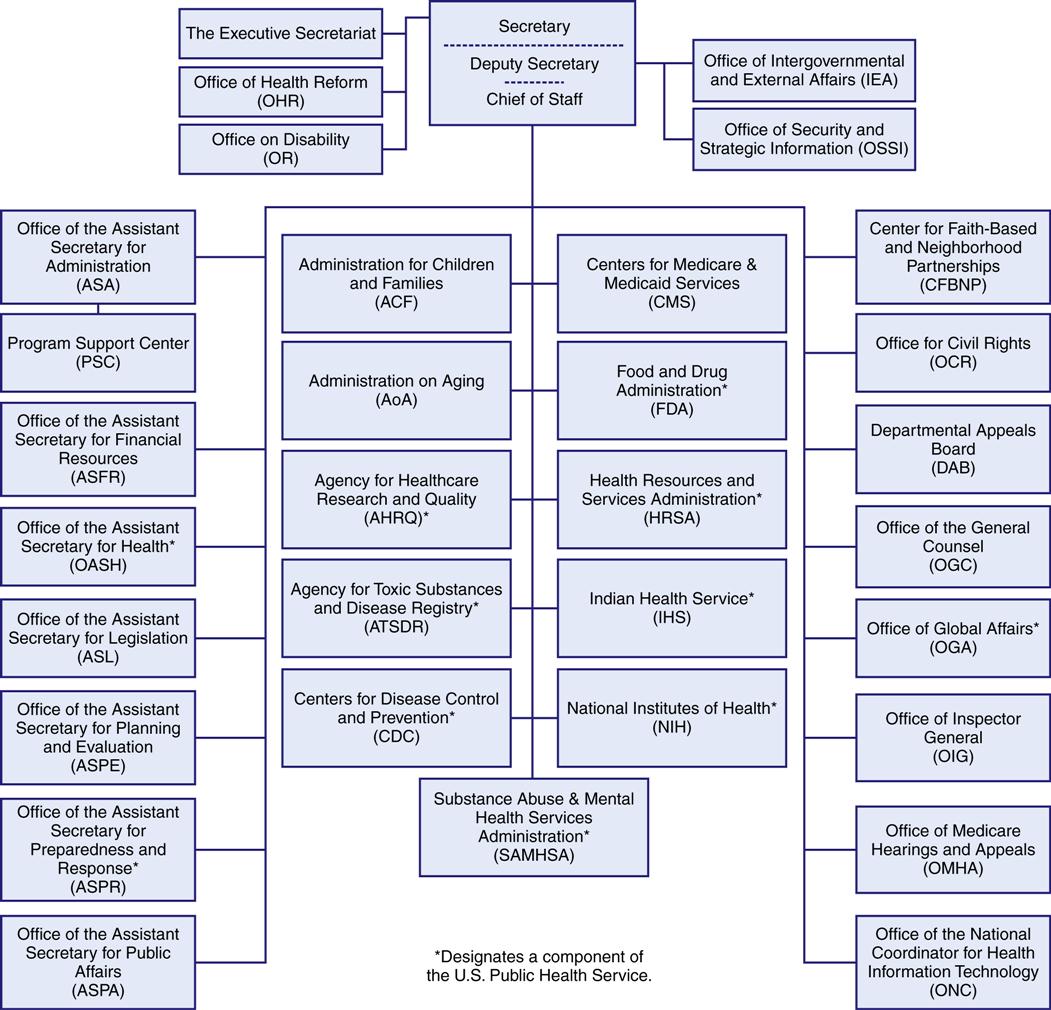

The federal agency with the most health-related responsibilities is the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). This department has more than 69,839 employees and an annual budget of $854.1 billion dollars (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012, Tables 499, 471). Although the USDHHS is responsible for some direct services, most of its activities involve indirect care, including health care planning and resource development, research, health care financing, and regulatory oversight. The USDHHS either carries out these services or delegates the responsibility and funding for services to other public and private organizations. The two largest public-sector health programs, Medicare and Medicaid, are supervised by the USDHHS. The organizational chart in Figure 3-6 illustrates some of the specific responsibilities of the USDHHS. The responsibilities of the USDHHS are varied and complex; because of space constraints, only some offices and their functions are described in this chapter. Public health and political science texts can provide a more in-depth discussion of the USDHHS for those who wish to investigate this area.

The USDHHS provides both public health and welfare services. Public health functions are provided by the following agencies:

• The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the primary source of information on communicable diseases and is a vital resource for all public health personnel. Box 3-3 details the scope of services provided by the CDC.

Office of Public Health and Science and the Surgeon General

In 1996, a reorganization of the USDHHS established all the agencies previously under the direction of the Public Health Service (PHS) as independent agencies. The Office of Public Health and Science (OPHS) performs the old administrative functions of the PHS and is responsible to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (Box 3-4). That reorganization and a subsequent reorganization dramatically reduced the influence and position of the Surgeon General, who now has little power in terms of directing health care policy. Before the reorganizations, the Surgeon General had responsibility for the CDC, the FDA, the IHS, and the NIH, and other departments, including the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps. Today, the Surgeon General serves in an advisory and educational capacity for public health matters but has no authority to formulate health care policy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree