Developing scenario

In accordance with the joint guidelines for best practice produced by the British Medical Association (BMA), the Resuscitation Council (UK) and the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) (2007), the consultant documents the discussion, Do Not Attempt Resuscitation decision and Alan’s palliative care plan. The nurse disconnects and removes unnecessary monitoring and infusions and ensures Alan is clean and appears comfortable prior to his family returning to sit with him. An intravenous opiate infusion is commenced whilst his blood pressure is still high enough to circulate the opiate round his body, to prevent discomfort and facilitate a feeling of calm.

The nurse explains to Alan’s family the provision of analgesia, sequence of stopping support and changes they can expect to see in Alan’s breathing, skin colour and conscious level as he dies. She invites them to ask questions and to express their needs throughout this process. The nurse offers the services of the hospital chaplain, which are declined. Alan appears slightly aware but does not respond. The nurse then stops the inotropic drug infusion, reduces the oxygen delivery from the ventilator to 21% (i.e. room air) and reduces the ventilatory support that Alan is receiving.

His son, David, appears agitated, leaving the bedside and returning frequently. He asks some irrational questions, demands specific answers, expresses his distrust of hospital staff and seems unable to provide support to his mother. The nurse initiates conversation with Mrs Smith, asking about their life together. Mrs Smith talks freely and cries at times. David joins in with memories of family activities and gradually settles at the bedside, providing some physical comfort to his mother. Alan dies approximately six hours later, with both the nurse and his family present.

An evidence-based discussion of management

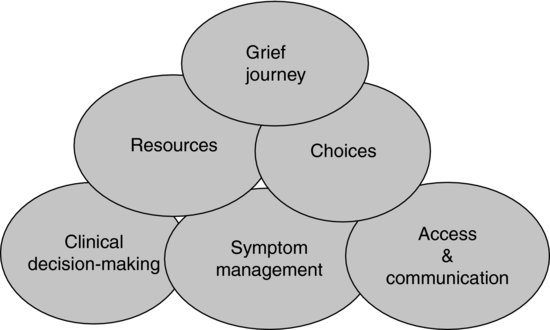

The care of Alan and that of his family are inextricably linked and need simultaneous management (Hall and Rocker 2000) (Figure 17.1).

Withdrawal of treatment plans and guidelines are increasingly used in critical care areas to aid accurate, unambiguous, thorough documentation and intra- and inter-professional collaboration, particularly when the withdrawal of treatment situation is especially complex (Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool (MCPCIL) 2007). Plans should be flexible enough to adapt to the changing needs of the patient and family during the dying process. The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) (Ellershaw and Wilkinson 2003) is a multi-professional document that provides an evidence-based framework that can be used during the last hours and days of life. It is based on the standards of care delivery in the hospice environment. Its aim is to improve care of the dying in the last hours or days of life, wherever the location, and to improve the knowledge related to the process of dying. The LCP is recommended as a template of best practice in UK national policy (DH 2008, 2009), and should guide the care of Alan and his family in the last hours or days of life. An example of the LCP template can be found at: http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/liverpool-care-pathway/pdfs/LCP-ICU-version11.pdf.

The dying process took several hours for Alan, providing an opportunity to utilise skills and creativity to influence the quality of his death and facilitate his family’s natural grieving process.

Symptom management

Withdrawal of treatment does not equate to withdrawal of care. Every effort should be made to maintain the highest standard of care to the patient (Hunter et al. 2006). Pain relief should be given a high priority. An intravenous opiate infusion was provided for Alan to enhance comfort, not to accelerate the dying process (Truog et al. 2001; Twycross 2003). Titration of analgesia according to need is an important nursing role. All other infusions (apart from those for the control of unpleasant symptoms), and monitoring, should be discontinued (Cohen et al. 2003). In Alan’s case, only cardiac monitoring was continued, at David’s request, with the screen angled away from Mrs Smith’s direct line of vision. This also enabled the nurse to monitor vital signs, such as tachycardia, that could indicate pain.

Truog et al. (2001) note that although guidelines suggest that any intervention that does not advance the patient’s goals should be eliminated, this simple advice can be difficult to follow in reality. An example of this can be seen in Alan’s care. Artificial nutrition and hydration are medical treatments and evidence from terminally ill cancer patients suggests that dying patients do not feel hunger or thirst in the later stages of death, and that their continuation can unnecessarily prolong death. However, Alan’s naso-gastric feed was continued, since David expressed particular fear that his father would feel thirsty or hungry, depriving him of a basic human right.

Alan’s ventilatory support was reduced to a minimum and his inotropic drugs discontinued. It would have been clinically appropriate to stop ventilation completely and just humidify the room air. Although he might have died more quickly, this may have increased his family’s distress, bearing in mind that they needed time to communicate with him and with each other as part of the grieving process. Alan could also have been extubated, however, again this could have led to symptoms for example, gasping or gurgling sounds, that could have been construed as distressing for both Alan and his family.

Family needs

Box 17.1 outlines key aspects of family needs during end-of-life care.

Box 17.1 Families’ needs during end of life care

To be present

To assist in care for their loved one

To be informed about changes and decisions

To understand the care being delivered and its rationale

To be confident that their loved one is comfortable and cared for at all times

To be comforted and have opportunity to express their feelings

To feel confident that the correct decisions have been taken

To achieve an understanding of the death of their loved one

To have their own physical needs provided for

Source: Adapted from Truog et al. (2001).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree