Perhaps one of the most important methods of pain control for Meena is through the use of drugs. The three main groups of analgesics used are opioids, non-opioids and adjuvants (drugs shown to enhance the effect of analgesics) (Godfrey 2005b). A combination of these can often produce synergistic effects in the critically ill patient.

The main non-opioid analgesics include paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin. The pharmacokinetics of paracetamol are not clearly understood, but may be related to COX-3 inhibition and inhibition of prostaglandin E2 (Godfrey 2005b). NSAIDs inhibit the production of cyclo-oxygenase, an enzyme involved in the production of prostaglandins. Given that prostaglandins are involved in activating and enhancing the pain response in the nociceptors, any reduction in their synthesis will help reduce pain. They could therefore be effective for Meena in helping to control any pain caused by inflammation due to surgery and for the chronic pain caused by her osteoarthritis. However, as NSAIDs commonly cause renal impairment and gastrointestinal disturbances such as gastric bleeding their use may be contraindicated in many critically ill patients.

Opioids work by binding with opioid receptors within the CNS, mimicking the effects of naturally occurring opioids, endorphins and enkephalins. Three types of opioid receptors are involved in producing an analgesic effect: mu (\umu) – which is most involved, kappa (k) and delta (∂). Opioids such as fentanyl and morphine exert full agonist effect at these receptors. Other opioids, such as buprenorphine, act as partial agonists, and as such do not have as much effect (Godfrey 2005b). Side effects of opioids include nausea, vomiting, respiratory depression, itching and constipation. Common routes of administration include oral, intramuscular, IV, transdermal (fentanyl patches, for example) and via epidurals. The use of patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) devices (see Figure 10.2) where the patient self-administers medication using an electronic pump device has been shown to be more effective than reliance on intramuscular analgesics, but not as effective as epidural administration (Dolin et al. 2002). Intramuscular injections are further contraindicated in the critically ill patient due to risks of bleeding and difficulty in accessing the muscle layer due to the common presence of systemic peripheral oedema.

Figure 10.2 PCA pump. (Adapted from: Flinders Biomedical Engineering. Available online at: http://www.flinders.edu.au/medicine/sites/biomedical-engineering/biomedical-engineering_ home.cfm. Used with permission.

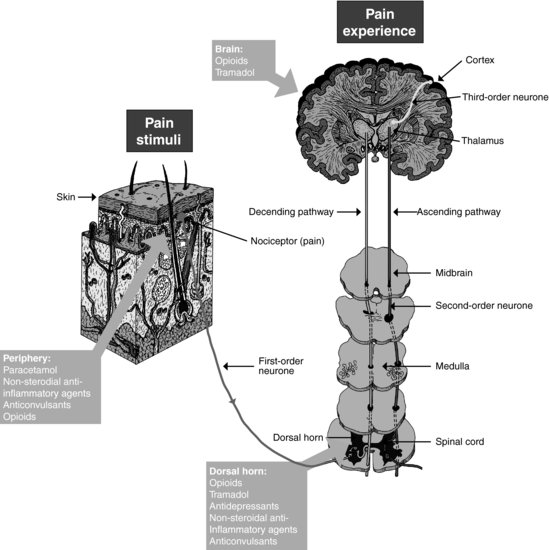

One drug that has both opioid and non-opioid analgesic effects is tramadol, which acts by binding with opioid receptors and inhibiting the re-uptake of two neurotransmitters within the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This has the effect of inhibiting the pain response (Godfrey 2005a). Other groups of drugs can also be considered, and in some instances, can reduce the dosage of opioids required. For example, low doses of tricyclic antidepressants are thought to inhibit the re-uptake of serotonin and noradrenaline in a similar way to tramadol, thus reducing pain perception at the level of the dorsal horn in the spinal cord (Godfrey 2005a). See Figure 10.3 for a summary of the location of drug actions along the pain pathway.

Ideally, administration of analgesics should be titrated against reported levels of pain, until an optimal level is achieved. If given at regular intervals, large fluctuations in blood plasma levels are avoided, and there is less chance of breakthrough pain, and less likelihood of side effects (Lynch 2001). It has also been shown that the use of opioids in adequate amounts will help prevent sensitisation and wind up (McHugh and McHugh 2000). Some authors suggest that another way of helping to avoid wind up would be to explain how it might occur and stressing to Meena the importance of seeking pain relief as soon as she feels she needs it (Carr 2007). The analgesic ladder, originally described by the World Health Organisation in 1996 (WHO 2010) would provide a useful framework for managing Meena’s analgesic requirements

As Meena is in severe pain, it is likely that opioids would be the analgesics of choice. As well as diminishing her perception of pain, opioids may also have a euphoric or anxiolytic effect. However, they can also result in sedation and respiratory depression. Given that Meena has already had a total of 10 mg intravenously, it would be worth assessing whether her drowsiness is due to the sedative effects of morphine. Keeping Meena informed of what the team were doing to relieve her pain, or using distraction, might also be useful.

Although pain is a common experience, particularly in surgical patients, research suggests that it is not well managed (Watt-Watson et al 2001; Puntillo et al 2002; Seers et al 2006; Gélinas 2007). Some of the reasons given for less than optimal pain control include nurses’ lack of knowledge of both the pathophysiology of pain and misconceptions surrounding the use of analgesics for treatment. Despite research indicating that the likelihood of addiction as a result of opioid analgesia for pain relief is less than 1%, many nurses believe that it is easy for a patient to become addicted (Ferrell et al. 1992). It has also been shown that many nurses fail to increase the dose of analgesia despite previous doses neither relieving the patients’ pain nor producing any side effects (Ferrell et al. 1992). Further, it has been demonstrated that nurses’ pain relief practices are influenced by the social contexts in which they work (Clabo 2008). Access to a wide range of information does not guarantee, however, that good decisions are made about pain management.

Conclusion

Managing pain is complex and made even more challenging by its subjective nature and the fact that it can be difficult to communicate with patients in the critical care setting. As patients deteriorate and require more complex care and management, time available to make adequate pain assessment and management decisions is reduced, and this important aspect of care can be compromised. As well as inadequate knowledge and information about how to treat pain, other variables that might compromise effective pain management include personal values and beliefs, staffing levels, the physical environment, the complexity of the patient and the interrelationships between members of the multi-disciplinary team and the patient and their families (Seers et al. 2006). Yet, allowing a patient to experience continuing pain has been shown to affect morbidity (Shannon and Bucknall 2003), and is a human rights issue. Somehow, pain assessment has to be included as the ‘fifth vital sign’, and managed accordingly. The whole multi-disciplinary team needs to work together to help ensure that a patient’s pain is well managed (Seers et al. 2006; Carr 2007). Nurses can play a central role. However, if they are to make informed clinical decisions, they need to be knowledgeable about pain processes and understand the effects of the range of drugs; opioids, non-opioids and adjuvants used to treat pain. They also need to take responsibility for managing pain, and do so competently (Seers et al. 2006).

Key learning points

- Pain is a common experience, yet because of the complex nature of critical care, it is not always adequately assessed or managed.

- The key to managing pain effectively is timely and continual assessment and re-assessment of a patient’s pain. It is important to ensure that the assessment of pain is considered as a ‘fifth vital sign’.

- Nurses must understand the underlying physiology of pain, and the effects of the range of drugs and other approaches used in its treatment.

- Although pharmacological methods of pain relief may be the treatment of choice within the critical care setting, other, non-pharmacological methods should also be considered.

Critical appraisal of research paper on pain

Clabo L (2008) An ethnography of pain assessment and the role of social context on two postoperative units. Journal of Advanced Nursing 16(5), 531–539.

This study was carried out in the United States of America on two post-operative units of one teaching hospital. The aim of the study was to examine pain assessment practices in both units in order to assess in what ways and to what extent the peri-operative pain assessment varied across the two units. The researcher also wanted to assess what the impact of the social context of each unit was on pain assessment practices.

Reader activities

1. Read the research article written by Clabo (2008).

2. Using the critical appraisal framework in Appendix I. consider the methodological quality of the paper.

3. Reflect on this aspect of your own practice and the implications for pain management in your unit that this paper raises.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree