The Nursing Center

A Model for Nursing Practice in the Community

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Describe key characteristics of nursing center models.

2. Explain community collaboration.

3. Identify interventions that address Healthy People 2020 goals.

4. Determine the feasibility of establishing and sustaining a nursing center.

5. Describe the roles and responsibilities of the advanced practice nurse in a nursing center.

6. Discuss the future of population-centered nursing practice, education, and research.

Key Terms

advanced practice nurses, p. 463

business plan, p. 472

community collaboration, p. 462

comprehensive primary health care, p. 465

convenient care clinics, p. 470

cost-effectiveness, p. 473

evidence-based practice, p. 474

feasibility study, p. 472

federally qualified health centers, p. 465

grants, p. 465

Healthy People 2020, p. 462

multilevel interventions, p. 462

National Nursing Centers Consortium, p. 465

Nurse-Family Partnership, p. 465

nurse-managed health center (NMHC), p. 462

nursing models of care, p. 463

organizational framework, p. 470

outcomes, p. 462

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (P.L. 111-148), p. 466

prevention levels, p. 469

primary health care, p. 464

program evaluation, p. 477

public health nurses, p. 465

quality care, p. 473

reimbursement systems, p. 464

special care centers, p. 465

stakeholders, p. 467

strategic planning, p. 468

sustainability, p. 469

wellness centers, p. 464

—See Glossary for definitions

Katherine K. Kinsey, PhD, RN, FAAN

Katherine K. Kinsey, PhD, RN, FAAN

Dr. Katherine K. Kinsey is the Principal Investigator and Administrator of the Philadelphia Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP), the Mabel Morris Early Head Start Program, and the First Steps Autism Spectrum Disorder Program. Dr. Kinsey previously directed a nationally recognized academic-based nurse-managed health center. She is a past chairperson of the American Public Health Association, Public Health Nursing Section. Dr. Kinsey serves on several non-profit boards and is the president of the Kingsley Family Foundation. The foundation is dedicated to improving the well-being of vulnerable, underserved populations. Dr. Kinsey has a particular interest in advancing public health nurses and nurse-managed health centers as mainstream primary health care providers in the twenty-first century.

Mary Ellen T. Miller, PhD, RN

Mary Ellen T. Miller, PhD, RN

Dr. Mary Ellen T. Miller is an Assistant Professor at De Sales University School of Nursing in Center Valley, PA and teaches in the undergraduate and graduate programs. Dr. Miller serves as Co-Chair of the Wellness Center Committee of the National Nursing Center Consortium. Previously, she served as the Associate Director of Public Health Programs for an academic nursing center. Dr. Miller has published works about nurse-managed centers and presents regionally and nationally on topics related to her work, as well as about student involvement with community service and learning, and about nurse-managed wellness centers. She is a member of the American Public Health Association, the American Nurses Association, Sigma Theta Tau International, Kappa Delta Chapter, and she serves on several non-profit boards.

Drs. Kinsey and Miller thank Marjorie Buchanan, MS, RN for her thoughtful contributions to the development of this chapter as well as chapter co-authorship in earlier editions of Public Health Nursing.

Considerable data document that nursing centers improve health outcomes. The nurse-managed health center (NMHC) model increases access to care; provides a more comprehensive approach to health and illness; decreases racial, ethnic, and geographic disparities in health status; and can potentially reduce the overall costs of health care. Nurse-managed health centers, as safety net providers, reach out to and engage underserved, vulnerable populations in public health and primary health care initiatives. This chapter describes nursing centers and their origins, evolution, and future directions. Emphasis is placed on the Healthy People 2020 framework, community collaboration, and multilevel interventions to improve access and reduce health disparities. This chapter describes nursing roles and responsibilities in delivering community-based services, managing center operations, and expanding initiatives for practice, research, and education in public health and primary care settings. Economic, social, political, national health care reform, and global factors influencing NMHC operations and population-centered nursing practice are discussed.

What are Nursing Centers? (also known as Nurse-Managed Health Centers or Clinics)

Overview and Definition

In 2011 and beyond, the terms nursing center, nurse-managed health center, and nurse-managed health clinic will be interchangeable and used to describe this model of health care. The citations in this eighth edition of Public Health Nursing: Population-Centered Health Care in the Community include historical references noted in earlier editions and current references regarding the evolution of NMHCs. The references frame the decades’ long NMHC movement. However, the acquisition of knowledge is undergoing metamorphosis. The introduction of new Internet-based technology and communication venues regarding public health programs and NMHCs will grow exponentially (Khan et al, 2010). Access to NMHCs initiatives, public health practice examples, and career opportunities are now featured on social networking websites, wikis, and blog communities. These venues, and others still in the research and development phases, will add rich content as NMHCs continue to transition into mainstream health care provider status.

In the past, the most frequently cited and referenced definition of nursing centers has been the one developed by the American Nurses Association (ANA) Nursing Centers Task Force in the mid-1980s (Box 21-1). However, the recently passed Nurse-Managed Health Clinic Investment Act of 2009 (Senate Bill 1104/House of Representatives Bill 2754) of the 111th Congress provides a more current and functional definition of nurse-managed health clinics with an amendment to Title III of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 241 et sez.) (Box 21-2).

Nursing centers provide unique opportunities to improve the health status of individuals, families, and communities through direct access to nurses and nursing models of care (Lancaster, 1999). All nursing centers possess characteristics that reflect the values, beliefs, and scientific knowledge and skills inherent in nursing models of care. Furthermore, each is guided, managed, and primarily staffed by nurses, thus ensuring that decision making and ultimate accountability for this model of care rest with professional nurses (Kinsey and Gerrity, 2005).

The NMHC is supported by the ANA seminal position paper titled Health Promotion and Disease Prevention (ANA, 1995). The paper recognizes health promotion strategies as pivotal points of any health care system designed to control costs and reduce human suffering. It acknowledges nursing’s scope of practice and underscores its efforts to focus on disease prevention interventions (ANA, 1995).

Nursing center models combine human caring, scientific knowledge about health and illness, and understanding of family and community characteristics, interests, assets, needs, and goals for health promotion, disease prevention, and disease management. Nursing center models de-emphasize illness-oriented and institutional care that has dominated health care since World War II and subscribe to a holistic perspective on improving personal, community, and societal well-being.

Nursing Models of Care

Nursing centers are strategically positioned to improve the health and well-being of vulnerable populations (Kinsey, 1999), build on the core values and beliefs of the profession (Matherlee, 1999), and reduce health disparities by providing access to comprehensive primary health care and health promotion and disease prevention services (Hansen-Turton, Miller, and Greiner, 2009) (Figure 21-1). Social determinants of health (Wilensky and Satcher, 2009) as well as the integration of trust, caring, personal respect, equity, and social justice perspectives serve as the foundation from which health is viewed as a resource for everyday life (Buchanan, 1997). Efforts of the center focus on enhancing people’s capacity to meet their personal, family, and community responsibilities and interests and typically include the following:

• A holistic approach to care based upon complex and interrelated biopsychosocial factors

• Community partnerships in establishing and supporting the center’s health efforts

Nursing center models combine people, place, approach, and strategy in everyday life to develop appropriate health interventions. Advanced practice nurses (APNs) work in close partnership with the communities they serve to provide public health programs, community-wide health education, and primary health care services. They establish relationships with families, community representatives, policy makers, and others in designing, implementing, and evaluating appropriate health intervention strategies, services, and programs (Zimmerman, Mieczkowski, and Wilson, 2002; Hansen-Turton, Miller, and Greiner, 2009).

A nursing center’s health and community orientation builds strong connections to the population served. These strong relationships with community leaders, residents, and clients foster a deep awareness of local factors that influence daily life (Lundeen, 1999). This orientation builds on Lillian Wald’s community work more than a century ago. Wald’s work to establish The Henry Street Visiting Nurse Service and a cadre of public health nurses who treated social and economic problems—not just infections, diseases, and providing care to the chronically ill—is part of the nursing center legacy (Fee and Bu, 2010).

Types of Nursing Centers

There are many types of nursing centers. Each has a “personality” of its own (Gerrity and Kinsey, 1999). A center’s mission, values, goals, and strategies, as well as its commitment to community well-being, contribute to its profile (Clear, Starbecker, and Kelly, 1999). Organizational structure (academic, non-academic), federal tax status (profit or non-profit), and reimbursement systems (fee for service, sliding scale fee rates, or no charge) also define centers. Other types will evolve due to the 2010 national health care reform legislation. The legislative initiatives include maximizing federally qualified health center services; increasing access to primary health care for people of all ages; introducing new public health, preventive health, and home visiting programs; and implementing and using electronic medical records. To date, most nursing centers fit into the types described in Box 21-3.

Wellness Centers

Wellness centers focus on health promotion, disease prevention, and management programs. APNs and others provide outreach and public awareness services, health education, immunizations, family assessment and screening services, home visiting, and social support (Evans et al, 1997; Hansen-Turton, Miller, and Greiner, 2009). Public health education and support programs may include smoking cessation (Lakon, Hipp, and Timberlake, 2010), weight management counseling, and parenting classes (Hurst and Osban, 2000). “Enabling” services help people access language translation, registration for entitlement programs, transportation vouchers, and specialty services. Healthy People 2020 goals and objectives provide direction to services planned, implemented, and evaluated through the wellness center model.

These centers complement existing primary care services. The staff maintains strong relationships with local health care providers in community health centers, clinics, private practices, long-term care facilities, and other organizations. In general, financial support for center programs comes from public health department and other service contracts, foundation grants, fee for services, voluntary contributions, and shared resources from affiliated organizations (Oros et al, 2001). In addition, these centers often serve as venues for community service learning activities for graduate and undergraduate students from multiple disciplines. Nursing centers extend learning beyond the classroom and into the community, providing a legitimate experience whereby students apply theoretical content to a community setting (Miller and Guigliano, 2006).

Special Care Centers

Some nursing centers focus on a particular demographic group or on those with special health care needs. Special care centers are responsive and provide services and specialized health knowledge and skills to a particular group, and they are an adjunct to comprehensive primary health care models. Examples of special care centers are those that focus on the needs of people with diabetes or HIV/AIDS, adolescent mothers, the frail elderly, and support services for people with mental disorders (Alakeson, Frank, and Katz, 2010).

Comprehensive Primary Health Care Centers

In many communities, nursing centers offer comprehensive primary health care. In addition to the health and wellness programs described previously, these centers also serve as the primary care (medical) home for families in the communities where they are located. Both physical and behavioral health care services are provided by nurse practitioners, other APNs, and allied health professionals. These centers address the needs of individuals and families across the life span, ensuring access to specialized health care as indicated. Public health nurses and community workers provide outreach, social support, and an array of public health programs. The public health programs include health education, screening, immunizations, lead poisoning prevention, home visitation such as the Nurse-Family Partnership, Early Head Start, environmental health initiatives, and other preventive community-based health services (Figure 21-2).

Comprehensive primary health care centers face the challenge of establishing systems for documenting clinical care and utilization patterns. These systems include demographic profiles, accounting support, billing mechanisms, reimbursement protocols, quality improvement strategies, and client satisfaction measures (Sherman, 2005). Nursing centers must meet standards established by government, insurers, health maintenance organizations, and other payers.

Some primary health centers are designated as federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) by the Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS). Their purposes are to (1) provide population-based comprehensive care in medically underserved areas and (2) maintain the appropriate mission, organizational, and governance structure according to the FQHC designation. These designations include community health center, public housing center, homeless center, or school based center.

The FQHC designation is important from a number of perspectives. Most importantly, it supports a primary care center’s efforts to serve low-income and uninsured populations and remain fiscally solvent. FQHCs receive federal grant funds from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to support operational expenses. They also receive cost-based payment for services provided to Medicare and Medicaid patients, Federal Tort Claim coverage, and 340b drug pricing, and they have the option to participate in the National Health Services Corps.

Many nursing centers need to overcome internal and external organizational hurdles to initiate the FQHC application process and receive funding approval (Torrisi and Hansen-Turton, 2005). The National Nursing Centers Consortium (NNCC), with offices in Philadelphia and Washington, DC, provides regional training for the FQHC application processes. By 2010, more nurse-managed primary care centers have achieved FQHC or “Look Alikes” status and are documenting clinical outcomes regarding chronic disease management as well as fiscal solvency that allows for site expansion. The recent passage of the Nurse-Managed Health Clinic Investment program by the 111th Congress holds great potential for additional NMHC-affiliated academic institutions to be eligible for FQHC status.

Many NMHCs are in non-profit academic settings. They are housed within or closely affiliated with schools of nursing. These NMHCs actively integrate service, education, and research in their model. They build upon public health and primary care nurse practitioner educational programs, draw upon the knowledge and skills of faculty, and provide rich learning experiences for nursing students at all levels. Furthermore, they use the knowledge, skills, and resources of other schools of health professions, business, communications, and law to expand the center’s service capacity (Shiber and D’Lugoff, 2002).

One example of an academic nurse-managed health center is the Lewis and Clark Community College Nurse-Managed Health Center located in Godfrey, Illinois. The college also has a mobile health unit. This NMHC was the first to open to the public on a U.S. community college campus. The center provides non-emergency, low-cost primary care services and partners with the Southern Illinois Healthcare Foundation for referrals and specialty care. Nursing students have clinical rotations through the NMHC and its mobile unit. Students and faculty are involved in client education and illness prevention services. This model introduces students to the expanding roles and responsibilities of APNs in community settings and career options (Weller, 2010).

Other centers may be affiliated with free-standing organizations, subsidiaries of health care or other human services organizations, or sponsored by an affiliate of such entities. Each of these organizational arrangements requires carefully established legal agreements. To conduct business, these organizations must become incorporated; apply to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) for a tax status designation; and receive a Statement of Tax Status Determination. Organizations are generally categorized as a non-profit (501(c)3) entity or some form of proprietary (for-profit) organization. The majority of nursing centers are with non-profit organizations; others fit within a proprietary business mode, and others operate as subsidiaries of established organizations. In all cases, staff must be familiar with the particular laws and regulations associated with the IRS tax status under which they operate.

Another way to describe nursing centers involves the health care system’s financial reimbursement methods that support services and programs. These include fee-for-service, designated HMO provider, Medicaid provider, Medicare provider, and FQHC status. Each designation requires a center to possess certain characteristics, meet a set of standards, and possess identification numbers that allow them to participate in billing and reimbursement systems.

Regardless of the type of nursing center, a wide array of personal, social, educational, economic, and environmental concerns indicate the need for and expansion of nursing centers. Increasing population density and diversity, challenging community conditions, and long-standing and emerging health problems indicate the role such models of care can play (Kinsey, 2002). The national health reform law, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, holds the potential for NMHCs to work with like entities to help improve the nation’s health. The new law and other legislative changes focus on reforming the health care system, increasing disease prevention initiatives and access to services, and containing or reducing health care expenditures (Thorpe and Ogden, 2010). The national commitment to build integrated delivery systems offers nursing centers and academic health systems new opportunities to demonstrate effectiveness, efficiency, and cost savings (Dentzer, 2010).

With the anticipation of NMHC expansion grants, it is essential to work with like-minded individuals and groups to share knowledge, resources, and lessons learned. Several organizations dedicated to the promotion and sustainability of NMHCs are in place to support its members through these expansion phases. The NNCC is one nationally recognized organization dedicated to this work. As of 2010, NNCC represents more than 200 members and is the largest national repository of member nurse–managed health centers. Its members represent organizations, programs within parent organizations, free-standing entities, and individuals invested in the nurse-managed center model. (A current membership list is available at www.nncc.us.) Members have the benefits of NNCC monthly newsletters, grant updates, current legislative and advocacy work, and its Annual National Conference. NNCC reaches out to non-profit organizations and individuals interested in establishing or expanding a nurse-managed health center (clinic) model. The Consortium often links members with potential members to share expertise and consult on program design and implementation.

Another consortium, The Michigan Academic Consortium (MAC), recently conducted a survey of all schools of nursing identified by the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The survey found that there are approximately 138 academic NMHCs. Additional information can be found through the Institute of Nursing Centers (http://www.nursingcenters.org/) and the Nursing Centers Research Network (http://www4.uwm.edu/nursing/ncrn/). According to NNCC surveys, there are an additional 112 NMHCs operating as non-profit organizations or through community colleges.

The Foundations of Nursing Center Development

The foundations for integrating primary care and public health services through the NMHC model include the perspective of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Healthy People 2020 systematic approach to improving individual and community health.

World Health Organization

The WHO’s (1978) definition of health and its framework to address global health supports an NMHC’s integration of primary care and public health services in community settings.

Healthy People 2020

The Healthy People initiative has framed the nation’s health promotion and disease prevention agenda since 1980. Its framework, vision, mission, goals, and objectives are developed to achieve better health for all by 2020. Healthy People represents a collaborative federal, public, and stakeholder process and accounts for global and national environmental, social, demographic changes, and trends such as the increasing older populations. Healthy People accommodates the escalating technological influences on personal and population health status, and incorporates anticipated changes in the U.S. sickness-oriented health system. Chapter two describes the history of Healthy People, and chapters throughout the text apply the objectives of Healthy People 2020 to their content. The concept of Healthy People 2020 builds on shared responsibility to improve the nation’s health. Communities, individuals, and systems have the potential for change, yet no one person or organization can do this alone. Powerful, productive partnerships among diverse people and groups and long-term commitments to community collaboration are needed to achieve Healthy People 2020 goals. NMHCs can help to achieve the goals and objectives of Healthy People 2020 and would emphasize those goals and objectives that fit the target populations’ needs. For example, an NMHC associated with an elementary school where more than 40% of the students are obese would select Healthy People 2020 objectives relative to childhood nutrition, physical activity, and exercise. The NMHC would also implement communication strategies that address the need to reduce childhood obesity in school-age children.

Community Collaboration

Nursing centers and APNs are well positioned to guide and facilitate community collaboration and engagement (Keefe, Leuner, and Laken, 2000; Bechtel and Ness, 2010). Productive collaboration requires staff expertise and commitment from many to change communication patterns, professional agendas, and speak in a common voice to generate positive community transformation (Cross and Prusak, 2002). The community transformations occur through policy, legislative, and funding changes that improve the health status of many and help design the patient-centered medical homes that include NMHCs (Landon et al, 2010).

Individuals, families, groups, organizations, policy makers, and staff are involved in the process. Referred to as stakeholders, each entity offers diversity in perspective. Their particular knowledge and skills enhance the community’s efforts to address critical needs, solve problems, and recognize unique strengths and resources. Stakeholders facilitate or undermine

strategic efforts to improve health. It is impossible to fully know and address issues and concerns in a community without having all perspectives heard and every stakeholder respectful of different opinions and experiences (Hansen-Turton and Kinsey, 2001; Bechtel and Ness, 2010).

Collaboration takes time, effort, and resources. It requires nurturing and support to make it work. Relationships among people and organizations serve as the foundation for the collaborative process and for community change. Relationships begin with introductions and open discussion to listen and learn from one another. From this, relationships grow toward a collective willingness to work together toward a common purpose, sharing risks, responsibilities, resources, and rewards along the way. The definition of collaboration developed by Mattessich and Monsey (1992) describes the work involved; they view collaboration as a relationship entered into by two or more groups to achieve common goals that are well defined and beneficial to all. There must be a respectful commitment to these goals with mutual accountability and authority that allows for shared responsibilities, resources, and successes. See Resource Tool 21.A: Factors Influencing the Success of Collaboration.

Nursing center staff require skills in networking, coordination, and cooperation in order to collaborate (Floyd, 2001). A number of basic agreements and interview strategies help set the stage for a long-term process of discussion, decision making, and action (Rollnick, Miller, and Butler, 2008). Once established, they are reviewed and rigorously adhered to throughout the life of the collaboration. These agreements are:

• Regular meetings where diverse perspectives are heard and respected

• A mutually agreed upon decision-making process

Mattessich and Monsey (1992) have identified six critical elements that contribute to the success of a collaborative endeavor: the environment, membership characteristics, process and structure of the group, communication patterns, purpose of the collaboration, and resources within and outside the group.

Perhaps the most important feature in community collaboration is the capacity of those involved to enhance the capacity of another person, group, or organization in service to the common purpose. For instance, rather than the nursing center serving as the lead organization, different participating organizations will serve from time to time in the leadership role, or hold greater responsibility, or perhaps receive additional funds to achieve the common purpose to which they all have subscribed. Through this, mutual benefit is realized by all (Goffee and Jones, 2001).

Each nursing center develops its philosophy, goals, and activities through a process of community collaboration, community assessment, and strategic planning. Strategic planning recognizes multiple levels of intervention required for bringing about and sustaining change. Often, community collaboration and assessment are concurrent activities.

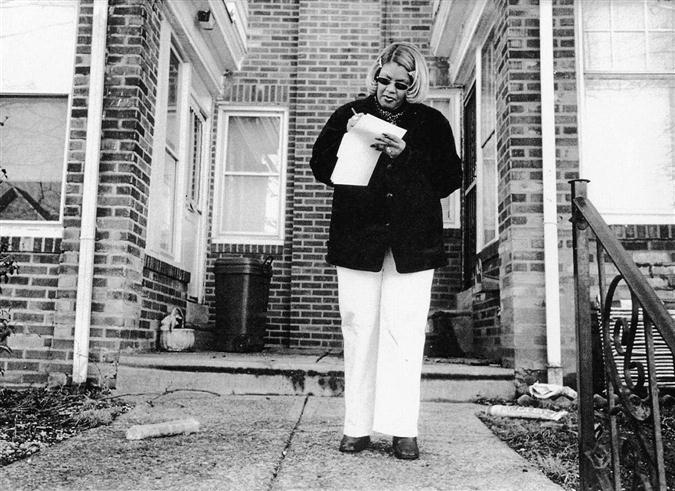

Community Assessment

Nurse-managed centers must conduct periodic community assessments. This chapter reemphasizes the importance of data and analysis of community needs and assets in determining the type of nursing center to establish or expand. Through the assessment process, nurses learn both the community’s formal and informal infrastructure and the communication networks through which everyday life takes place (Baker, White, and Lichtveld, 2001). Neighborhood walks, bus rides, car trips, and discussions with elected officials, administrators of health care systems, public health department staff, and community members provide insight into the community’s health and the many other influencing factors (Figure 21-3). Also, historical, ethnographic multimedia news features add context to the community assessment (Anderson, 1999).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree