Public Health Nursing at Local, State, and National Levels

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

2. Identify trends in public health nursing.

3. Provide examples of public health nursing roles.

4. Differentiate the emerging public health issues that specifically affect public health nursing.

5. Describe collaborative partnerships.

6. Explain the principles of partnership.

7. Identify educational preparation of public health nurses and competencies necessary to practice.

Key Terms

federal public health agencies, p. 990

incident commander, p. 1001

local public health agencies, p. 991

partnerships, p. 990

public health, p. 990

public health nursing, p. 994

public health programs, p. 990

state public health agency, p. 991

–See Glossary for definitions

Diane V. Downing, RN, PhD

Diane V. Downing, RN, PhD

Diane V. Downing began practicing public health nursing in 1980 as a public health nurse with the Marion County Health Department in Indiana. She also worked at the local level as Assistant Commissioner for Nursing and Quality Assurance in the New York City Department of Health and Nurse Manager with Arlington Department of Human Services. She has worked at the state level in Indiana as the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome project coordinator, as division director for local health standards and evaluation, and as Division Director for the Maternal and Child Health Division. At the national level, she worked as the Director of the Policy and Research Division of the Public Health Foundation. She currently teaches public health nursing at Georgetown University School of Nursing and Health Studies in Washington, DC. She advocates for vulnerable populations and public health needs as a member of the Public Health Nursing Section Leadership, American Public Health Association. She represents Community-Campus Partnerships for Health on the Council of Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice. The Council on Linkages Between Academia and Public Health Practice, located in Washington, DC, and funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a coalition of representatives from 17 national public health organizations. The Council works to further academic/practice collaboration to ensure a well-trained, competent public health work force and a strong, evidence-based public health infrastructure.

All of public health is built on partnerships. Public health programs are designed with the goal of improving a population’s health status. They go beyond the administration of health care to individuals to a primary focus on the health of populations. Public health programs include community health assessment and interventions based on assessment results, analysis of health statistics, public education, outreach, case management, advocacy, professional education for providers, disease surveillance and investigation, emergency preparedness and response, compliance to regulations for some institutions/agencies and school systems, and follow-up of populations. Examples of follow-up care include communicating with persons with active, untreated tuberculosis, pregnant women who have not kept prenatal visits, and parents of under-immunized children. Public health programs are frequently implemented by the development of partnerships or coalitions with other providers, agencies, and groups in the location being served. Community-Campus Partnerships for Health (CCPH) defines partnerships as “a close mutual cooperation between parties having common interests, responsibilities, privileges and power” (CCPH, 2006). Partnerships are built on trust, mutual respect, and the sharing of power.

Box 46-1 presents principles of partnerships. Public health nurses are skilled at developing, sustaining, and evaluating community-wide partnerships. Public health nurses are involved in these activities in various ways depending on the public health agency (local, state, or federal) and the identified needs. Public health nurses may be the partnership facilitator or a member of the partnership representing their agency.

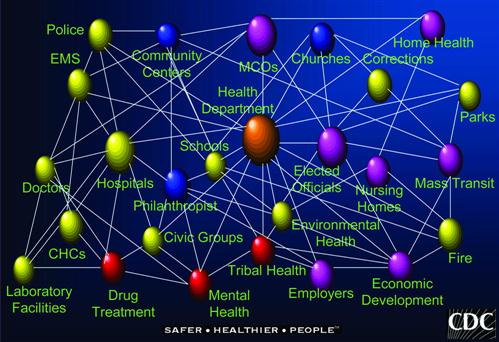

Public health is not a branch of medicine; it is an organized community approach designed to prevent disease, promote health, and protect populations. It works across many disciplines and is based on the scientific core of epidemiology (IOM, 1988, 2003a). Governmental agencies at the local, state, and federal levels are partners in the public health system that must work together to develop and implement solutions that will improve a community’s health. Figure 46-1 represents the diverse and complex network of individuals and agencies making up the public health system (CDC, 2005a). Public health nurses partner with interprofessional teams of people within the public health areas (Figure 46-2), in other human services and public safety agencies, and in community-based organizations. The health of communities is a shared responsibility that requires a variety of diverse and often non-traditional partnerships. A critical partnership that shapes public health nursing practice in the United States is the interaction of local, state, and federal public health agencies.

Roles of Local, State, and Federal Public Health Agencies

In the United States, the local-state-federal partnership includes federal agencies, the state and territorial public health agencies, and the 3200 local public health agencies. The interaction of these agencies is critical to effectively leverage precious resources, both financial and personnel, and to protect and promote the health of populations. Public health nurses employed in all of these agencies work together to identify, develop, and implement interventions that will improve and maintain the nation’s health.

Federal public health agencies develop regulations that implement policies formulated by Congress, provide a significant amount of funding to state and territorial health agencies for public health activities, survey the nation’s health status and health needs, set practices and standards, provide expertise that facilitates evidence-based practice, coordinate public health activities that cross state lines, and support health services research (IOM, 2003a). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) are the federal agencies that most influence public health activities at the state and local levels (see Chapter 3). The USDHHS includes the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The USDHHS is the agency that facilitates development of the nation’s Healthy People objectives (USDHHS, 2010).

In the United States, states hold primary responsibility for protecting the public’s health. Each of the states and territories has a single identified official state public health agency that is managed by a state health commissioner. The structure of state public health agencies varies. Some states require that the state health commissioner be a physician. A growing number of states do not limit the position to physicians but rather require specific public health experience. California, Maryland, Iowa, Oregon, Washington, and Michigan are examples of states that focus on public health experience as a requirement for the state health commissioner position. Public health nurses have been appointed to the state health commissioner positions in a number of states. For example, public health nurses have been appointed to health commissioner positions in the states of California, Oregon, Washington, and Michigan. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials defines the state public health agency as the organizational unit of the state health officer, who works in partnership with other government agencies, private enterprises, and voluntary organizations to ensure that services essential to the public’s health are provided for all populations. State public health agencies are responsible for monitoring health status and enforcing laws and regulations that protect and improve the public’s health. In addition to state funds appropriated by state legislatures, these agencies receive funding from federal agencies for the implementation of public health interventions, such as communicable disease programs, maternal and child health programs, chronic disease prevention programs, and injury prevention programs. The agencies distribute federal and state funds to the local public health agencies to implement programs at the community level, and they provide oversight and consultation for local public health agencies. State health agencies also delegate some public health powers, such as the power to quarantine, to local health officers.

Local public health agencies have responsibilities that vary depending on the locality, but they are the agencies that are responsible for implementing and enforcing local, state, and federal public health codes and ordinances and providing essential public health programs to a community. The goal of the local public health department is to safeguard the public’s health and to improve the community’s health status. The health department’s authority is delegated by the state for specific functions. The duties of local health departments vary depending on the state and local public health codes and ordinances and the responsibilities assigned by the state and local governments. Usually, the local public health department provides for the administration, regulatory oversight, public health, and environmental services for a geographical area. The National Association of County and City Health Officials’ (NACCHO) operational definition of a local health department provides a description of the basic public health protections people in any community, regardless of size, can expect from their local health department. The definition provides standards within the 10 essential public health services (NACCHO, 2005). A sample of these standards can be found in Box 46-2. As with state health departments, some states require that local health directors be physicians, whereas other states focus on public health experience. For example, public health nurses in Maryland, Illinois, Washington, Wisconsin, and California hold local health director positions.

The majority of local, state, and federal public health agencies will be involved in the following:

• Collecting and analyzing vital statistics (Chapter 12)

• Providing health education and information to the population served (Chapter 16)

• Receiving reports about and investigating and controlling communicable diseases (Chapter 13)

• Planning for and responding to natural and man-made disasters and emergencies (Chapter 23)

• Protecting the environment to reduce the risk to health (Chapter 10)

• Providing some health services to particular populations at risk or with limited access to care (local public health agencies, guided by state and federal policies and goals and community needs) (Chapters 27 to 31, 38 to 46)

• Conducting community assessments to identify community assets and gaps (Chapter 18)

• Identifying public health problems for at-risk and high-risk populations (Chapter 18)

• Partnering with other organizations to develop and implement responses to identified public health concerns (Chapters 18 and 25)

Public health nurses practice in partnership with each other at the local, state, and federal levels and with other public health staff, other governmental agencies, and the community to safeguard the public’s health and to improve the community’s health status. Public health agency staffs include physicians, nutritionists, environmental health professionals, health educators, various laboratory workers, epidemiologists, health planners, and paraprofessional home visitors and outreach workers. Community-based organizations include the American Red Cross, free clinics, Head Start programs, daycare centers, community health centers, hospitals, senior centers, advocacy groups, churches, academic institutions, and businesses. Other governmental agencies include the fire/emergency services department, law enforcement agencies, schools, parks and recreation departments, and elected officials. Changes in local, state, and federal governments affect public health services, and public health nursing has to develop strategies for dealing with these changes. Public health nurses facilitate community assessments to identify emerging public health concerns within communities and, based on results of community assessments, help develop programs to provide needed services.

.

History and Trends in Public Health

A person born today can expect to live 30 years longer than a person born in 1900. Medical care accounts for 5 years of that increase. Public health practice, resulting in changes in social policies, community actions, and individual and group behavior, is responsible for the additional 25 years of that increase (USDHHS, 2009). Historically, public health nurses were valued by and important to society and functioned in an autonomous setting. They worked with populations and in settings that were not of interest to other health care disciplines or groups. Much public health service was delivered to the poor and to women and children, who did not have political power or voice. During the course of the twentieth century, public health responsibilities expanded beyond communicable disease prevention, occupational health, and environmental health programs to include reproductive health, chronic disease prevention, and injury prevention activities. As a result of Medicaid-managed care, many public health agencies were no longer providing personal health care services. Public health agencies began to shift emphasis from a focus on primary health care services to a focus on core public health activities such as the investigation and control of diseases and injuries, community health assessment, community health planning, and involvement in environmental health activities. As the twentieth century came to a close, developments in genetic engineering, the emergence of new communicable diseases, prevention of bioterrorism and violence, and the management and disposal of hazardous waste were emerging as additional public health issues (CDC, 1999). The Institute of Medicine (IOM, 2003a) identified the following seven priorities for public health in the twenty-first century:

• Understand and emphasize the broad determinants of health.

• Develop a policy focus on population health.

• Strengthen the public health infrastructure.

• Develop systems of accountability.

• Emphasize evidence-based practice.

Public health activities at the beginning of the twenty-first century were shaped by the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks of the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Pennsylvania, in which thousands were murdered. However, public health nursing activities at the federal, state, and local levels were even more dramatically affected by a series of anthrax exposures that occurred shortly after the terrorist attacks. In addition to anthrax exposures in Florida and New York, 1 month after the attacks of September 11, thousands of workers at the Brentwood Post Office and the Senate Building in Washington, DC, were exposed to an especially virulent strain of anthrax from a contaminated letter. These exposures required public health nurses to rapidly establish mass medication distribution clinics, while also responding to frightened calls from community members and requests for information from the media. The anthrax exposures alerted policy makers to the weakening public health infrastructure required to respond to bioterrorism events. As society grapples with the upheaval created by the reality of a bioterrorism event, public health nurses learn to leverage existing authority and expertise to ensure that all critical issues threatening the public’s health are addressed. The shift of funding to support bioterrorism response efforts has the potential of weakening existing important public health programs. Nurses are well positioned to actively participate in policy decisions that will ensure that a public health infrastructure able to prevent and respond to bioterrorism will be strengthened and maintained within the context of general communicable disease surveillance and response. Public health nurses are facing issues such as unprecedented influenza, tetanus, and childhood vaccine shortages and emerging infections, such as SARS and the influenza A virus (H1N1) pandemic, that compete with bioterrorism activities for resources. One of these issues presented itself in the fall of 2009 and spring of 2010 when the world grappled with enough vaccine to prevent H1N1 as the virus was spread across the world. (See later discussion.)

During the twentieth century, public health nurses were a major force in the nation, achieving immunization rates that accounted for the dramatic decrease in measles. A policy brief issued by All Kids Count (2000, p 1) stated “in 1941, more than 894,000 cases of measles were reported in the U.S. In 1998, preliminary data indicated that just 100 cases were reported—a reduction of 99.9%.” However, the general public was not informed about how this immunization activity was accomplished or about its effect on improving health and lowering health care costs. Public health nurses’ difficulty explaining the value of ongoing prevention activities can result in a decrease in resources required to ensure adequate surveillance and containment of communicable disease outbreaks. For public health services to receive adequate funding, it is necessary for the public and the government to be aware of the benefits provided to a community by public health nurses. Public health nurses must be at the table, as advocates and experts, when issues are being discussed and decisions are being made to make certain that public health programs are provided for the populations at risk. For example, as the incidence of active tuberculosis (TB) cases decreases, officials will consider shifting funds for TB control to other efforts. Public health nurses at the national, state, and local levels work together to educate officials about the importance of continuing funding for surveillance and containment efforts if the lower TB incidence rates are to be maintained.

The twenty-first century public health nurse is working to develop a public health system able to monitor and detect suspicious trends and respond rapidly to prevent widespread exposure, whether the result of a deliberate or a natural epidemic. A prime example of emerging infectious diseases is severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), caused by a virus that brought illness and death to many in 2003. The disease spread quickly from China to other countries, being transported by airline passengers traveling internationally. The novel H1N1 influenza A virus pandemic provides another example of a natural epidemic that required a rapid, intensive, long-term response from public health nurses at the federal, state, and local levels. In 2009, the world was alerted to a new rapidly spreading influenza A virus (H1N1) when Mexico declared a state of emergency and closed schools and congregations in public settings in response to outbreaks of respiratory illness and increased reports of clients with influenza-like illness in several areas of the country (CDC, 2009). The first U.S. human cases of H1N1 were identified in April 2009 in California and Texas. On October 24, 2009, President Barack Obama declared H1N1 a national emergency in the United States. Public health nurses throughout the country shifted their activities to support the response to H1N1. Public health nurses who usually worked in areas such as family health services or school health services rapidly had to shift their focus to the H1N1 response. Family health service clinics and home visiting services were either cancelled or scaled back to free up public health nurse time to respond to the emerging pandemic.

Scope, Standards, and Roles of Public Health Nursing

In 1920 C. E. A. Winslow defined public health as “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health and efficiency through organized community effort” (Turnock, 2010, p 10). This definition is still used in public health textbooks because it focuses on the relationship between social conditions and health across all levels of society. The IOM defines public health practice as “what we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy” (IOM, 2003a, p 28). Reflecting these definitions, the Public Health Nursing Section of the American Public Health Association defined public health nursing as “the practice of promoting and protecting the health of populations using knowledge from nursing, social and public health sciences” (APHA, 1996, p 1). The American Nurses Association (ANA) adds that public health nursing is a population-focused practice that works to promote health and prevent disease for the entire population. Public health nursing is a specialty practice of nursing defined by scope of practice and not by practice setting (ANA, 2007).

Additional knowledge, skills, and aptitudes are necessary for a nurse to go beyond focusing on the health needs of the individual to focusing on the health needs of populations (see Chapters 1 and 18). This additional knowledge distinguishes the public health nurse from other nurses who are practicing in the community setting. Public health nursing practices arise from knowledge gained from the physical and social sciences, psychological and spiritual fields, environmental areas, political arena, epidemiology, economics, community organization, public health ethics, community-based participatory research, and global health. The Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations identified eight principles (Box 46-3) that distinguish the public health nursing specialty from other nursing specialties. Although other nurses may practice some or all of these eight principles, they are not incorporated as a core foundation of the practice in other specialties. Public health nurses always adhere to all eight principles of public health nursing (ANA, 2007).