Economics of Health Care Delivery

Objectives

After reading this chapter, the student should be able to do the following:

1. Relate public health and economic principles to nursing and health care.

2. Describe the economic theories of microeconomics and macroeconomics.

3. Identify major factors influencing national health care spending.

4. Analyze the role of government and other third-party payers in health care financing.

5. Identify mechanisms for public health financing of services.

6. Discuss the implications of health care rationing from an economic perspective.

7. Evaluate levels of prevention as they relate to public health economics.

Key Terms

budget limits, p. 101

business cycle, p. 102

capitation, p. 121

cost–benefit analysis, p. 103

cost-effectiveness analysis, p. 103

cost-utility analysis, p. 103

demand, p. 101

diagnosis-related groups, p. 116

economic growth, p. 103

economics, p. 100

effectiveness, p. 102

efficiency, p. 102

enabling, p. 118

fee-for-service, p. 106

gross domestic product, p. 103

gross national product, p. 103

health care rationing, p. 104

health economics, p. 100

human capital, p. 102

inflation, p. 99

intensity, p. 106

investment in public health, p. 99

macroeconomic theory, p. 102

managed care, p. 119

managed competition, p. 120

market, p. 101

means testing, p. 112

Medicaid, p. 114

medical technology, p. 106

Medicare, p. 114

microeconomic theory, p. 101

prospective payment system, p. 115

public health economics, p. 100

public health finance, p. 100

quality of adjusted life-years, p. 103

retrospective reimbursement, p. 120

safety net providers, p. 105

supply, p. 101

third-party payer, p. 119

—See Glossary for definitions

Marcia Stanhope, RN, DSN, FAAN

Marcia Stanhope, RN, DSN, FAAN

Dr. Marcia Stanhope is currently a professor at the University of Kentucky College of Nursing, Lexington, Kentucky. She has been appointed to the Good Samaritan Foundation Chair and Professorship in Community Health Nursing. She has practiced community and home health nursing and has served as an administrator and consultant in home health, and she has been involved in the development of two nurse-managed centers. She has taught community health, public health, epidemiology, primary care nursing, and administration courses. Dr. Stanhope formerly directed the Division of Community Health Nursing and Administration and was Associate Dean in the College of Nursing at the University of Kentucky. She has been responsible for both undergraduate and graduate courses in community-oriented nursing. She has also taught at the University of Virginia and the University of Alabama, Birmingham. Her presentations and publications have been in the areas of home health, community health and community-focused nursing practice, nurse managed centers, and primary care nursing.

There is strong evidence to suggest that poverty can be directly related to poorer health outcomes. Poorer health outcomes lead to reduced educational outcomes for children, poor nutrition, low productivity in the adult workforce, and unstable economic growth in a population, community, or nation. However, improving health status and economic health is dependent on the “degree of equality” in policies that improve living standards for all members of a population including the poor. To move toward improving a population’s health, there must be an “investment in public health” by all levels of government (Anderson et al, 2006).

Estimates indicate that public spending on health care makes a difference but needs the support of increased private health care spending to improve the overall health status of populations (Trust for America’s Health, 2009). Several facts are known from the literature (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009; Mantone, 2006; NCPP, 2007; RWJF, 2009; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010):

• Approximately 49.4 million (16%) of an estimated 308.4 million people in the United States are without health insurance. This number is expected to grow rapidly by 2015 (RWJF, 2009; U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

• More than 8 in 10 (80%) of the uninsured are in working families (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009).

• About 66% are from families with one or more full-time workers.

• 14% are from families with part-time workers.

• Only 19% of the uninsured are from families that have no connection to the workforce.

• The poor are not as healthy as persons with middle to higher incomes.

• The poor are more likely to receive health care through publicly funded agencies.

Approximately 97% of all health care dollars are spent for individual care whereas only 3% are spent on population level health care. The 3% includes monies spent by the government on public health as well as the preventive health care dollars spent by private sources. These numbers indicate that there is not a large investment in the public’s health or population health in the United States (NCHS, 2010).

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation. The cost of health care has been rising more than the rate of inflation since the mid 1960s, yet the U.S. population does not enjoy better health as compared with nations that spend far less than the United States. The current health care system is at the point where it is not affordable (Turnock, 2008); Trust for America’s Health, 2009). According to Trust for America’s Health (2009), an estimated $10 per person invested in community-based prevention programs can lead to improved health status of the population and reduced health care costs. This return on investment represents medical cost savings only and does not include the significant gains that could be achieved in worker productivity, reduced absenteeism at work and school, and enhanced quality of life.

Nurses are challenged to implement changes in practice and participate in research, evidence-based practice, and policy activities designed to provide the best return on investment of health care dollars (i.e., to design models of care, at a reasonable price, that improve access or quality of care). Meeting this challenge requires a basic understanding of the economics of the U.S. health care system. Nurses should be aware of the effects of nursing practice on the delivery of cost-effective care.

Public Health and Economics

Economics is the science concerned with the use of resources, including the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Health economics is concerned with how scarce resources affect the health care industry (McPake and Normand, 2008). Public health economics then focuses on the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services as related to public health and where limited public resources might best be spent to save lives or best increase the quality of life (WordIQ.com, 2010). Economics provides the means to evaluate society’s attainment of its wants and needs in relation to limited resources. In addition to the day-to-day decision-making about the use of resources, there is a focus on evaluating economics in health care (McPake and Normand, 2008). While in the past there has been limited focus on evaluating public health economics, it is becoming more obvious what evaluating public health and preventive care can do in terms of cost savings and, more importantly, quality of life (Trust for America’s Health, 2009). This type of evaluation will help to present challenges to public policy makers (legislators). Public health financing often causes conflict because the views and priorities of individuals and groups in society may differ with those of the public health care industry. If money is spent on public health care, then money for other public needs, such as education, transportation, recreation, and defense, may be limited. When trying to argue that more money should be spent for population-level health care or prevention, data are becoming available that show the investment is a good one. Public health finance is a growing field of science and practice that involves the acquiring, managing, and using of monies to improve the health of populations through disease prevention and health promotion strategies. This field of study also focuses on evaluating the use of the money and the impact on the public health system (Honoré, 2008).

Although the public health system had been considered for many years as involving only government public health agencies such as health departments, today the public health system is known to be much broader and includes schools, industry, media, environmental protection agencies, voluntary organizations, civic groups, local police and fire departments, religious organizations, industry/business, and private sector health care systems, including the insurance industry. All can play a key role in improving population health (IOM, 2003; Trust for America’s Health, 2009).

The goal of public health finance is “to support population focused preventive health services” (Honoré, 2008). Four principles are suggested that explain how public health financing may occur.

• The source and use of monies are controlled solely by the government.

• The government controls the money, but the private sector controls how the money is used.

• The private sector controls the money, but the government controls how the money is used.

• The private sector controls the money and how it is used (Gillespie et al, 2004; Moulton et al, 2004).

When the government provides the funding and controls the use, the monies come from taxes, user fees (e.g., license fees and purchase of alcohol/cigarettes), and charges to consumers of the services. Services offered at the federal government level include the following:

• Collecting and sharing information about U.S. health care and delivery systems

• Building capacity for population health

Select examples of services offered at the state and local levels include the following:

• Preventing communicable and infectious diseases

• Direct care services (see Chapter 46 for more examples)

When the government provides the money but the private sector decides how it is used, the money comes from business and individual tax savings related to private spending for illness prevention care. When a business provides disease prevention and health promotion services to its employees and sometimes families, such as immunizations, health screenings, and counseling, the business taxes owed to the government are reduced. This is considered a means by which the government provides money through tax savings to businesses to use for population health care.

When the private sector provides the money but the government decides how it is used, either voluntarily or involuntarily, the money is used for preventive care services for specific populations. A voluntary example is the private contributions made to reaching Healthy People 2010 goals. An involuntary example is the Occupational Safety and Health Administration requiring industry to adhere to certain safety standards for use of machinery, air quality, ventilation, and eyewear protection to reduce disease and injury. This, for example, has the effect of reducing occupation-related injuries in the population as a whole.

When the private sector is responsible for both the money and its use of resources, the benefits incurred are many. For example, an industry may offer influenza vaccine clinics for workers and families that may lead to “herd immunity” in the community (see Chapter 12 on epidemiology). A business or community may institute a “no-smoking” policy that reduces the risk of smoking-related illnesses to workers, family, and the consumers of the businesses’ services. A voluntary philanthropic organization may give a local school money to provide preventive care and health education to the children of the school (Stanhope et al, 2008).

These are but a few examples of how public health services and the ensuring of a healthy population are not only government related. The partnerships between government and the private sector are necessary to improve the overall health status of populations.

Principles of Economics

Knowledge about health economics is particularly important to nurses because they are the ones who are often in a position to allocate resources to solve a problem or to design, plan, coordinate, and evaluate community-based health services and programs. Two branches of economics are important to understand for their application in health care: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Microeconomic theory deals with the behaviors of individuals and organizations and the effects of those behaviors on prices, costs, and the allocating and distributing of resources. Economic behaviors are based on: (1) individual or organization choices and the consumer’s level of satisfaction with a particular good (product) or service, or use, and (2) the amount of money available to an individual or organization to spend on a particular good or service (its budget limits). Microeconomics applied to health care looks at the behaviors of individuals and organizations that result from tradeoffs in the use of a service and budget limits.

The microeconomic example of the industry providing preventive services to its employees represents a behavior by the industry that provides for the use of a service and helps the industry’s budget by reducing health care insurance premium costs. The terms of the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act (2010) allow employers to provide incentive rewards to employees for participation in wellness programs. Providing the service also increases worker productivity and promotes a healthier workforce, thus enhancing economic growth (Hall, 2010).

Because of the unique characteristics of health care, some economists believe that health care is special. There are debates about whether health care markets can ensure that health care is delivered efficiently to consumers. Cost–benefit and cost-effectiveness analyses are techniques used to judge the effect of interventions and policies on a particular outcome, such as health status (Veney and Kaluzny, 2005).

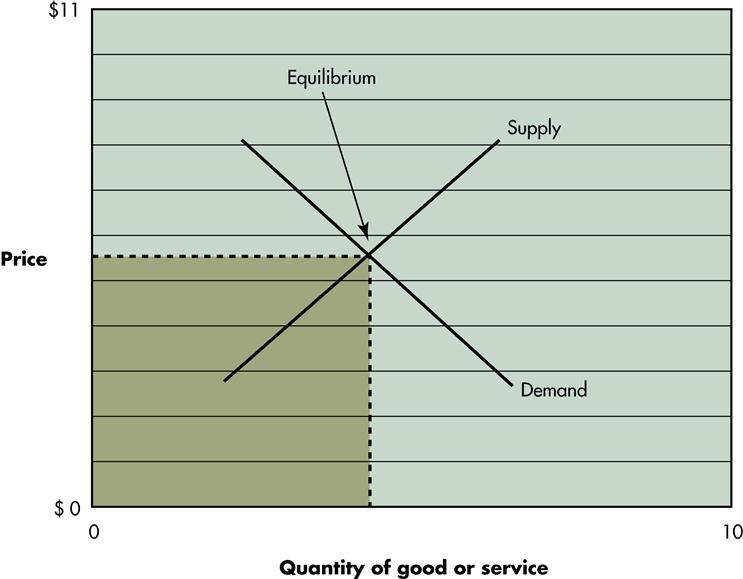

Supply and Demand

Two basic principles of microeconomic theory are supply and demand, both of which are affected by price. A simple illustration of the relationship between supply and demand is provided in Figure 5-1. The upward-sloping supply curve represents the seller’s side of the market, and the downward-sloping demand curve reflects the buyer’s desire for a given product. As shown here, suppliers are willing to offer increasing amounts of a good or service in the market for an increasing price (Colander, 2008). The demand curve represents the amount of a good or service the consumer is willing to purchase at a certain price. This curve illustrates that when few quantities of a good or service are available in the marketplace, the price tends to be higher than when larger quantities are available. The point on the curve where the supply and demand curves cross is the equilibrium, or the point where producer and consumer desires meet. Supply and demand curves can shift up or down as a result of the following factors (McPate and Normand, 2008):

• Competition for a good or service

• An increase in the costs of materials used to make a product

• A change in consumer preferences

Box 5-1 provides a review of the laws of supply and demand.

Using the example of industry-offered health care, it is not likely that a small industry of fewer than 50 employees may be able to offer incentive based on-site illness prevention services. The demand may be great to keep employees healthy and on the job. The supply is limited by the cost and numbers of services available in the community. Therefore, the cost is likely to be higher for the small business than for the large industry that offers its own services.

Efficiency and Effectiveness

Two other terms are related to microeconomics: efficiency and effectiveness. Efficiency refers to producing maximal output, such as a good or service, using a given set of resources (or inputs), such as labor, time, and available money. Efficiency suggests that the inputs are combined and used in such a way that there is no better way to produce the service, or output, and that no other improvements can be made. The word efficiency often focuses on time, or speed in performing tasks, and the minimizing of waste, or unused input, during production. Although these notions are true, efficiency depends on tasks as well as processes of producing a good or service and the improvements made (Veney and Kaluzny, 2005).

Effectiveness, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which a health care service meets a stated goal or objective, or how well a program or service achieves what is intended. For example, the effectiveness of a mass immunization program is related to the level of “herd immunity” developed to reduce the problem that the program was addressing (see Chapter 12). Box 5-2 illustrates the differences between efficiency and effectiveness (Veney and Kaluzny, 2005).

Macroeconomics

Microeconomics focuses on the individual or an organization, whereas macroeconomic theory focuses on the “big picture”—the total, or aggregate, of all individuals and organizations (e.g., behaviors such as growth, expansion, or decline of an aggregate). In macroeconomics, the aggregate is usually a country or nation. Factors such as levels of income, employment, general price levels, and rate of economic growth are important. This aggregate approach reflects, for example, the contribution of all organizations and groups within health care, or all industry within the United States, including health care, on the nation’s economic outlook.

The primary focuses of macroeconomics are the business cycle and economic growth. Business expands and contracts in cycles. These cycles are influenced by a number of factors, such as political changes (a new president is elected), policy changes (a new legislation is implemented, like the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act of 2010), knowledge and technology advances (a new vaccine to treat H1N1 is placed on the market), or simply the belief by a recognized business leader that the cycle is or should be shifting (e.g., when the head of the Federal Reserve Board changes interest rates).

The human capital approach is a measure of macroeconomic theory (Goodwin et al, 2008). In this approach improving human qualities, such as health, are a focus for developing and spending money on goods and services because health is valued; it increases productivity, enhances the income-earning ability of people, and improves the economy. Therefore, there is a positive rate of return on the “investment in human capital.” The individual, population, community, and nation all benefit. If the population is healthy, premature morbidity and mortality is reduced, chronic disease and disability are reduced, and economic losses to the nation are reduced.

Measures of Economic Growth

Economic growth reflects an increase in the output of a nation. Two common measures of economic growth are the gross national product (GNP) and the gross domestic product (GDP). GNP is the total market value of all goods and services produced in an economy during a period of time (e.g., quarterly or annually). GDP is the total market value of the output of labor and property located in the United States (USDHHS, 2004). GDP reflects only the national U.S. output, whereas GNP reflects national output plus income earned by U.S. businesses or citizens, whether within the United States or internationally. This discussion focuses on GDP, because U.S. health care spending reports are based on GDP (NCHS, 2010).

Nurses face microeconomic and macroeconomic issues every day. For example, they are influenced by microeconomics when referring clients for services, informing clients and others of the cost of services, assessing community need for a particular service, evaluating client access to services, and determining health provider and agency response to client needs. Nurses who work with aggregates of individuals and communities are faced with macroeconomic issues, such as health policies that make the development of new programs possible; local, state, and federal budgets that support certain programs; and the total effect that services will have on improving the health of the community and reducing the poverty level of the population. In short, knowledge about health economics can enhance a nurse’s ability to understand and argue a position for meeting population health needs.

Economic Analysis Tools

The primary methods used to assess the economics of an intervention are cost–benefit analysis (CBA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), and cost-utility analysis (CUA). CBA is considered the best of these methods. In simple form, CBA involves the listing of all costs and benefits that are expected to occur from an intervention during a prescribed time. Costs and benefits are adjusted for time and inflation. If the total benefits are greater than the total costs, the intervention has a net positive value (NPV). Future or continued funding is given to the intervention with the highest NPV. This technique provides a way to estimate overall program and social benefits in terms of net costs.

CBA requires that all costs and benefits be known and be able to be quantified in dollars; herein lies the major problem with its use. Although it is fairly easy to estimate the direct dollar costs of a health care program, it is often very difficult to quantify the non-dollar benefits and indirect costs. For example, benefits and costs could come in the form of increased income and expenses, which are fairly easy to measure. More difficult to measure are benefits such as improved community welfare resulting from a particular program, and the costs to the community that would result if the program did not exist. The value of potential lives lost because of lack of access to health care services is one example. The potential for a great number of lives lost from H1N1 resulted in the development of programs and monies invested with pharmaceutical companies in an attempt to reduce the risk of lives lost should the U.S. experience an epidemic from this disease risk. Although benefits could only be assumed from the cost investment, it was determined that the investment was essential (CDC, 2009).

CEA expresses the net direct and indirect costs and cost savings in terms of a defined health outcome. The total net costs are calculated and divided by the number of health outcomes. Although the data required for CEA are the same as for CBA, CEA does not require that a dollar value be put on the outcome (e.g., on an outcome such as quality of life). CEA is best used when comparing two or more strategies or interventions that have the same health outcome in the population. Both CEA and CBA are useful to nurses as they conduct community needs analyses and develop, propose, implement, and evaluate programs to meet community health needs. In both cases, the cost of a particular program or intervention is examined relative to the money spent and outcomes achieved.

An objective commonly used when CEA is performed in health care is improvement in quality of adjusted life-years (QALYs) for clients. QALYs are the sum of years of life multiplied by the quality of life in each of those years. The QALY assigns a value, ranging between 0 (death) and 1 (perfect health), to reflect quality of life during a given period of years (Hazen, 2007). In conducting a CEA, the cost of a program or an intervention is compared with real or expected improvements in clients’ quality of life. The How To box lists the steps involved in conducting a CEA. The QALY is often used in malpractice suits to award money to clients who have been injured by health care.

Depending on program or intervention goals, the most effective means of providing a service is not necessarily the least costly, particularly in the short run. This is particularly true in public health, when the cost-effectiveness of a preventive service may not be known until sometime in the future. For example, the total cost savings of a community no-smoking program might be difficult to project 10 years into the future. After 10 years, the number of lung cancer cases or deaths that have occurred can be compared with those in the 10 years before the program, and the cost-effectiveness of the no-smoking program can be shown. The Trust for America’s Health (2008), along with a number of other agencies, is publishing reports that are beginning to show positive results and cost savings from prevention programs.

Factors Affecting Resource Allocation in Health Care

The distribution of health care is affected largely by the way in which health care is financed in the United States. Third-party coverage, whether public or private, greatly affects the distribution of health care. Also, socioeconomic status affects health care consumption, since it determines the ability to purchase insurance or to pay directly out-of-pocket. The effects of barriers to health care access and the effects of health care rationing on the distribution of health care follow. Although the barriers are still issues, it remains to be determined how health care reform of 2010 will change the barriers to access and distribution.

The Uninsured

In 1996 68% of the total U.S. population had private health insurance. An additional 15% received insurance through public programs, and 17%, or 37 million, were uninsured. In 2006 the number of uninsured persons had increased to 46 million. The typical uninsured person is a member of the workforce or a dependent of this worker. Uninsured workers are likely to be in low-paying jobs, part-time or temporary jobs, or jobs at small businesses (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009). These uninsured workers cannot afford to purchase health insurance, or their employers may not offer health insurance as a benefit. Others who are typically uninsured are young adults (especially young men), minorities, persons less than 65 years of age in good or fair health, and the poor or near poor. These individuals may be unable to afford insurance, may lack access to job-based coverage, or, because of their age or good health status, may not perceive the need for insurance. Because of the eligibility requirements for Medicaid, the near poor are actually more likely to be uninsured than the poor.

Because of frustrations with the problems of lack of health insurance, The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010. This bill became law as a result of a promise to the American public by President Obama that health care reform would occur as part of his presidential agenda. Basically this law speaks to the following:

• Quality, affordable health care for all Americans

• A defined role of public programs

• Improving the quality and efficiency of health care

• Prevention of chronic disease and improving public health

• Transparency and program integrity

• Improving access to innovative medical therapies

• Community living assistance services and supports

Prior to the passing of this act,

• Twenty-five states were considering making it mandatory for employers to provide insurance coverage

• Seven states were looking at approaches to universal coverage

• Six states were considering the development of universal health care plan commissions

However, only three states had passed comprehensive health care reform by 2008: Massachusetts, Maine, and Vermont. State fiscal capacity, structural deficits, and then a worsening economy and severe state budget shortfalls limited states’ ability to further advance coverage initiatives. Although the experiences of pace-setting states will inform future federal action, the fiscal crisis makes it difficult for many states to achieve health care reform on their own.

As the health care reform debate progresses, the impact of federal reform on states will have differential effects. In general, states with more extensive poverty, higher budget shortfalls, lower eligibility levels for public programs, higher rates of uninsured, and more primary care shortages will be greatly affected (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010a).

The Poor

Socioeconomic status is inversely related to mortality and morbidity for almost every disease. Poor Americans with an income below poverty level have a mortality rate nearly several times greater than that of middle-income Americans, even after accounting for age, sex, race, education, and risky health behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking, overeating, and lack of exercise). Historically, the link between poor health and socioeconomic status resulted from poor housing, malnutrition, inadequate sanitation, and hazardous occupations. Today, explanations include the cumulative effects of a number of characteristics that explain the concept of poverty. These characteristics include low educational levels, unemployment or low occupational status (blue collar or unskilled laborer), low wages, being a child or an older person over the age of 65 years, or being a member of a minority group (NCHS, 2010).

Access to Care

Access to care is a public health issue (Healthy People 2020). Medicaid is intended to improve access to health care for the poor. Although persons with Medicaid have improved access compared with the uninsured, Medicaid recipients are only about half as likely to obtain needed health services (e.g., medical-surgical care, dental care, prescription drugs, and eyeglasses) as the privately insured. Specifically, the poorest Americans have Medicaid insurance, yet they also have the worst health (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2009).

The primary reasons for delay, difficulty, or failure to access care include inability to afford health care and a variety of insurance-related reasons, including the insurer not approving, covering, or paying for care; the client having preexisting conditions; and physicians refusing to accept the insurance plan. Other barriers include lack of transportation, physical barriers, communication problems, child care needs, lack of time or information, or refusal of services by providers. In addition, lack of after-hours care, long office waits, and long travel distance are cited as access barriers. Community characteristics also contribute to individuals’ ability to access care. For example, the limited prevalence of managed care and the limited number of safety net providers, as well as the wealth and size of the community, affect accessibility.

Because reimbursement for services provided to Medicaid recipients has been low, physicians are discouraged from serving this population. Thus, people on Medicaid frequently have no primary care provider and may rely on the emergency department for primary care services. Although physicians can respond to monetary incentives in client selection, emergency departments are required by law to evaluate every client regardless of ability to pay. Emergency department co-payments are modest and are frequently waived if the client is unable to pay. Thus, low out-of-pocket costs provide incentives for Medicaid clients and the uninsured to use emergency departments for primary care services.

With the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act (PL 111-148), some of the issues and barriers that have previously existed may disappear. This depends on whether Congress decides to repeal all or part of PL 111-148 or change some of the mandates in the law. By 2014 Medicaid recipients may benefit from the law in its current structure as follows: (1) expansion of Medicaid to include all non-Medicare eligible persons under age 65 with incomes up to 133% of federal poverty level, (2) all Medicaid-eligible persons will be guaranteed a benchmark benefit package, and (3) states will be given the option to develop a basic health plan for uninsured individuals who do not qualify for the Medicaid program, at 133% to 200% of poverty level.

Poverty level income is adjusted annually for each state by the federal government to indicate how much money an individual or families may earn to qualify for subsidies such as food stamps, Medicaid, and Children’s Health Insurance Program. In 2010 the federal poverty level for an individual was $10,830; for a family of four the poverty level was $22,050. If an individual was 133% of poverty level, then the individual earned no more than $14,403 (USDHHS, 2010).

Rationing Health Care

Rationing health care in any form implies reduced access to care and potential decreases in acceptable quality of services offered. For example, a health provider’s refusal to accept Medicare or Medicaid clients is a form of rationing. As with access to care, rationing health care is a public health issue. Where care is not provided, the public health system and nurses must ensure that essential clinical services are available. Managed care was thought to offer the possibility of more appropriate health care access and better-organized care to meet basic health care needs of the total population. A shift in the general approach to health care from a reactionary, acute-care orientation toward a proactive, primary prevention orientation is necessary to achieve not only a more cost-effective but also a more equitable health care system in the United States. PL 111-148, while providing coverage to more people, will not do away with rationing because the new law provides for a four-tiered plan (bronze, silver, gold, and platinum) by creating state-based American Health Benefit Exchanges. Persons at differing levels of poverty will have reductions in out-of-pocket expenses based on income up to 400% of poverty level and may receive tax credits and subsidies to assist with out-of-pocket expenses.

Healthy People 2020

Healthy People 2020 goals are examples of strategies to provide better access for all people. The Levels of Prevention box shows the levels of economic prevention strategies.

Primary Prevention

Society’s investment in the health care system has been based on the premise that more health services will result in better health, but non–health care factors also have an effect. Of the major factors that affect health—personal biology and behavior (or lifestyle), environmental factors and policies (including physical, social, health, cultural, and economic environments), social networks, living and working conditions, and the health care system—medical services are said to have the least effect. Behavior and lifestyle have been shown to have the greatest effect, with the environment and biology accounting for the greatest effect on the development of all illnesses (NCHS, 2009).

Despite the significant impact of behavior and environment on health, estimates indicate that 97% of health care dollars are spent on secondary and tertiary care. Such a reactionary, secondary-care system results in high-cost, high-technology, and disease-specific care and is consistent with the U.S. system’s traditional emphasis on “sickness care.” A more proactive investment in disease prevention and health promotion targeted at improving health behaviors, lifestyle, and the environment has the potential to improve health status of populations, thereby improving quality of life while reducing health care costs. The USDHHS has argued that a higher value should be placed on primary prevention. The goal of this approach is to preserve and maximize human capital by providing health promotion and social practices that result in less disease. An emphasis on primary prevention may reduce dollars spent and increase quality of life.

The return on investment in primary prevention through gains in human capital has not been acknowledged in the past, unfortunately. Consequently, large investments in primary prevention and public health care have not been made. Reasons given for this lack of emphasis on prevention in clinical practice and lack of financial investment in prevention include the following:

• Provider uncertainty about which clients should receive services and at what intervals

• Lack of information about preventive services

• Negative attitudes about the importance of preventive care

• Lack of time for delivery of preventive services

• Delayed or absent feedback regarding success of preventive measures

• Less reimbursement for these services than curative services

• Lack of organization to deliver preventive services

• Lack of use of services by the poor and elderly

• More out-of-pocket expenses for the poor and those who lack health insurance

A focus on prevention could mean reducing the need for and use of medical, dental, hospital, and health provider services. Under fee-for-service payment arrangements, this would mean that the health care system, the largest employer in the United States, would be reduced in size and would become less profitable. However, with the increasing costs of health care and consumer demand and the changes in financing mechanisms, there is a new trend toward financing more preventive care services.

Today, third-party payers are beginning to cover preventive services, recognizing that the growth of the health care system can no longer be supported. Under capitated health plans, health care providers stand to make money by keeping clients healthy and reducing health care use. Through combining client interests with financial interests of the health care industry, primary prevention and public health can be raised to the status and priority of acute care and chronic care. Despite difficulties, methods for determining prevention effectiveness, such as CEAs and CBAs, are becoming standard and used more widely. Two agendas for preventive services are published that promote the preventive agenda:

Regardless of the method, prevention-effectiveness analyses (PEAs) are outcome oriented. This area of research seeks to link interventions with health outcomes and economic outcomes, and to reveal the tradeoffs between the two. In theory, support for increasing national investment in primary prevention is sound and long standing. Since the public health movement of the mid-nineteenth century, public health officials, epidemiologists, and nurses have been working to advance the agenda of primary prevention to the forefront of the health care industry. Today, these efforts continue across a number of disciplines and in both the public and the private sectors, and through the efforts for health care reform (PL 111-148, 2010).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree