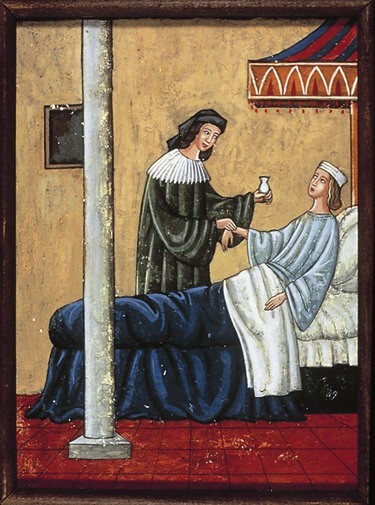

1. Describe the role of medical office care in the health care system. 2. Describe the historical development of managed care. 3. Identify the flow of activity in ambulatory care. 4. Identify the various types of health care professionals, and describe the job responsibilities of each professional. 5. State the educational requirements for physicians. 6. List and describe the parts of the medical office. 7. Identify and describe the various types of medical specialties. 8. Identify three medical practice types. 9. Compare and contrast various complementary and traditional medical treatments. Most treatments are based on scientific study. In Western scientific medicine, as in no other medical tradition, approaches to diagnosis and treatment have been studied and tested over hundreds of years. As long ago as the fourth century BC, a physician named Hippocrates in Greece believed that disease was not a punishment for transgressions against the gods, but rather the result of physiologic and environmental factors that could be studied. Since the time of Hippocrates, the practice of medicine has changed considerably in response to scientific discoveries (Table 1-1). Table 1-1 Milestones in the History of Medicine

The Health Care System

Introduction to Health and the Health Care System

3000 BC

Writings about the circulation of blood in China.

c. 460 BC

Birth of Hippocrates (called the “Father of Medicine”) in Greece—based medical care on observation and believed that illness was a natural biologic event.

1514-1564

Andreas Vesalius—wrote the first relatively correct anatomy textbook.

1578-1657

William Harvey—discovered circulation of blood (England).

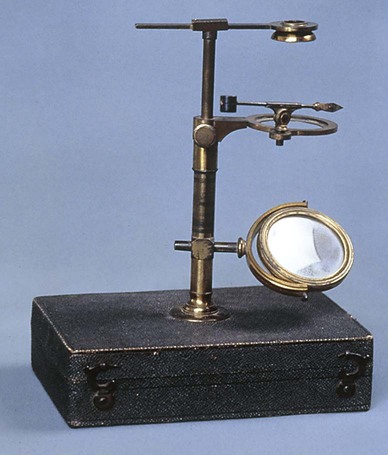

1632-1723

Antony van Leeuwenhoek—discovered the microscope (Holland).

1728-1793

John Hunter—developed surgical techniques used in surgery.

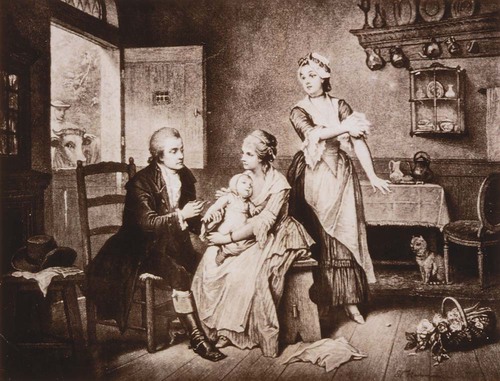

1749-1823

Edward Jenner—first vaccine for smallpox (England).

1818-1865

Ignaz Semmelweis—theorized that handwashing prevents childbirth fever (Austria); his theories were rejected during his lifetime and not accepted until the work of Pasteur and Lister.

1820-1910

Florence Nightingale—began training for nurses; established first nursing school; before this time nurses received no training and the profession had little status (England).

1821-1910

Elizabeth Blackwell—first woman to complete medical school in the United States; established a medical school in Europe for women only.

1821-1912

Clara Barton—acted as a nurse on the battlefields of the Civil War; was a civil rights activist and suffragette; organized the American Red Cross.

1822-1895

Louis Pasteur—developed pasteurization of wine, beer, and milk to prevent growth of microorganisms; microbiology (France).

1827-1912

Joseph Lister—demonstrated that microorganisms cause illness; his experiments with phenol, carbolic acid, and other antiseptics laid the groundwork for modern surgery (England).

Mid-1800s

First large hospitals, such as Bellevue, Johns Hopkins, and Massachusetts General, established in U.S. cities. Discovery of anesthesia in the United States is credited to a Southern physician named Crawford Williamson Long.

1843-1910

Robert Koch—isolated the bacteria that cause anthrax and cholera; established principles to determine that a specific type of bacteria causes a specific disease (Germany).

1845-1923

Wilhelm Roentgen—discovered x-rays (Germany) based on the discovery of radium and radioactivity by Marie Curie (1867-1934) and Pierre Curie (1859-1906).

1851-1902

Walter Reed—proved that yellow fever is transmitted by mosquitoes, not direct contact, while working as a U. S. army physician in Cuba. An aggressive spraying program made it possible to complete the Panama Canal.

1854-1915

Paul Ehrlich—coined the term chemotherapy; predicted autoimmunity; developed Salvarsan (arsphenamine), an effective treatment for syphilis, in 1909. This led to the development of sulfa drugs and other antibiotics (Germany).

1881-1955

Alexander Fleming—discovered penicillin (England); identified it in 1929, but an efficient method of producing large amounts was not developed until needed in World War II. Other antibiotic medications such as sulfa were soon discovered.

1891-1941

Frederick Banting—co-discoverer of insulin with Charles Best and John Macleod in 1922 (Canada).

1906-1993

Albert Sabin—developed oral polio vaccine.

1914-1995

Jonas Salk—developed parenteral polio vaccine.

1922-2001

Christiaan Neethling Barnard—South African surgeon who is remembered for succeeding at the first human-to-human heart transplant in 1967.

1978

Birth of Louise Joy Brown, the first child born by in vitro fertilization, in Great Britain.

The Health Care System

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access