The Drug Approval Process

Objectives

• Discuss the federal legislation acts related to U.S. Food and Drug Administration drug approvals.

• Explain the Canadian schedules for drugs sold in Canada.

• Describe the function of nurse practice acts.

• Differentiate between chemical, generic, and brand names of drugs.

Key Terms

American Hospital Formulary Service Drug Information, p. 19

brand (trade) name, p. 18

chemical name, p. 18

controlled substances, p. 16

Drug Enforcement Administration, p. 16

generic name, p. 18

malfeasance, p. 17

misfeasance, p. 17

nonfeasance, p. 17

United States Pharmacopeia—Drug Information, p. 19

United States Pharmacopeia National Formulary, p. 14

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, p. 14

Approval of new drugs by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has been steady since the early 2000s; the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has averaged 23 approvals per year. In 2004, the FDA established its Critical Path Initiative, a national strategy “to drive innovation in the scientific processes through which medical products are developed, evaluated, and manufactured.” One focus is on “improving the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of rare and neglected disorders.” Successes of the initiative include developing biomarkers and other scientific tools, streamlining clinical trials, and ensuring product safety.

Drug Standards and Legislation

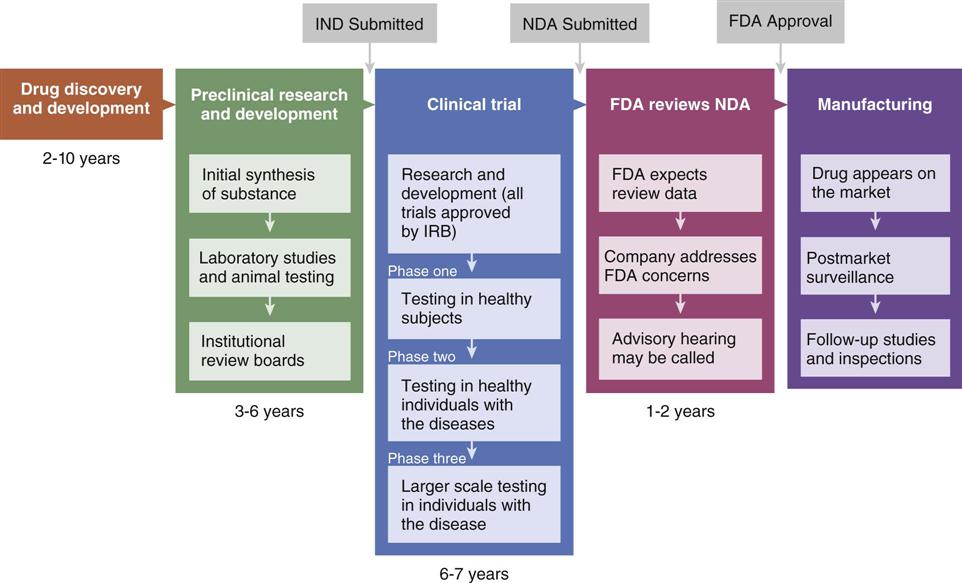

The combination of drug discovery and manufacturing takes 12 to 20 years, with a cost of more than $1 billion. Only a small percentage of drugs are approved. The steps of the process are shown in Figure 2-1.

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IND, Investigation of New Drug; NDA, New Drug Application.

Drug Standards

The set of drug standards used in the United States is the United States Pharmacopeia of 1820. The United States Pharmacopeia National Formulary (USP-NF), the current three-volume authoritative source for drug standards, is an annual publication with two supplements. Experts in nursing, pharmaceutics, pharmacology, chemistry, and microbiology all contribute. Drugs included in the USP-NF have met high standards for therapeutic use, patient safety, quality, purity, strength, packaging safety, and dosage form. Drugs that meet these standards have the initials “USP” following their official name, denoting global recognition of high quality. The USP-NF is the official publication for drugs marketed in the United States, so designated by the U.S. Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

The International Pharmacopeia, first published in 1951 by the World Health Organization (WHO), provides a basis for standards in strength and composition of drugs for use throughout the world. The book is published in English, Spanish, and French. The fourth edition (Volumes I and II) was published in 2006, with the first supplement in 2008.

Federal Legislation

Through federal legislation, the public is protected from drugs that are impure, toxic, ineffective, or not tested before public sale. The primary purpose of the legislation is to ensure safety. America’s first law to regulate drugs was the Federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which did not include drug effectiveness and drug safety.

1938: Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 empowered the FDA to ensure drug safety by monitoring and regulating the manufacture and marketing of drugs. It is the FDA’s responsibility to ensure that all drugs are tested for harmful effects, have labels with accurate information, and enclose detailed literature in the drug packaging that explains adverse effects. The FDA can prevent the marketing of any drug it judges to be incompletely tested or dangerous. Only drugs considered safe by the FDA are approved for marketing.

1952: Durham-Humphrey Amendment to the 1938 Act

The Durham-Humphrey Amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 distinguished between drugs that can be sold with or without prescription and those that should not be refilled without a new prescription. Those drugs that should not be refilled without a new prescription, such as narcotics, hypnotics, or tranquilizers, must be so labeled.

1962: Kefauver-Harris Amendment to the 1938 Act

The Kefauver-Harris Amendment to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 resulted from the widely publicized thalidomide tragedy of the 1950s in which European patients who took the sedative-hypnotic thalidomide during the first trimester of pregnancy gave birth to infants with extreme limb deformities. The Kefauver-Harris amendment tightened controls on drug safety, especially experimental drugs, and required that adverse reactions and contraindications must be labeled and included in the literature. The amendment also included provisions for the evaluation of testing methods used by manufacturers, the process for withdrawal of approved drugs when safety and effectiveness were in doubt, and the establishment of effectiveness of new drugs before marketing.

1970: The Controlled Substances Act

In 1970, Congress passed the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act, Title II. This act, designed to remedy the escalating problem of drug abuse, included several provisions: (1) promotion of drug education and research into the prevention and treatment of drug dependence; (2) strengthening of enforcement authority; (3) establishment of treatment and rehabilitation facilities; and (4) designation of schedules, or categories, for controlled substances according to abuse liability.

Controlled substances are described in five schedules, or categories, and are listed in Table 2-1. Schedule I drugs are not approved for medical use; schedule II through V drugs have accepted medical use. In addition, the abuse potential and extent of physical and psychological dependence are greatest with schedule I drugs. This dependency decreases as one moves through the schedule, with schedule V drugs having only limited abuse potential. Some drugs might be listed in more than one schedule category. Codeine is a schedule II drug, but when it is added to acetaminophen, it becomes a schedule III drug, and when it is used in combination as a cough preparation, it becomes a schedule V drug.

TABLE 2-1

SCHEDULE CATEGORIES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES

| SCHEDULE | EXAMPLES OF SUBSTANCES | DESCRIPTION |

| I | Heroin, hallucinogens (LSD, marijuana [except when prescribed with cancer treatment], mescaline, peyote, psilocybin) | High potential for drug abuse. No accepted medical use. Labeled C-I. |

| II | Meperidine (Demerol), morphine, hydrocodone (Hycodan), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), methadone (Dolophine), oxycodone (Oxy-Contin), codeine, amphetamines, secobarbital, pentobarbital (Nembutal) | High potential for drug abuse. Accepted medical use. Can lead to strong physical and psychological dependency. Labeled C-II. |

| III | Codeine preparations, paregoric, nonnarcotic drugs (e.g., pentazocine [Talwin]) | Medically accepted drugs. Potential abuse is less than that for schedules I and II. May cause dependence. Labeled C-III. |

| IV | Phenobarbital (Luminal), benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam [Valium], oxazepam [Serax], lorazepam [Ativan], chlordiazepoxide [Librium]), chloral hydrate (Aquachloral), meprobamate | Medically accepted drugs. May cause dependence. Labeled C-IV. |

| V | Opioid-controlled substances for diarrhea and cough (e.g., codeine in cough preparations) | Medically accepted drugs. Very limited potential for dependence. Labeled C-V. |

Nursing interventions for controlled substances are as follows:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree