Substance-Related Disorders

Substance abuse and addiction has serious medical and social consequences; the use of alcohol and other drugs can have an enormous impact on a person’s physical, mental and emotional health.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain the disease concept of alcoholism and the following theories of addiction: biologic, genetic, behavioral and learning, sociocultural, psychodynamic.

Differentiate among the following terms: substance use, addiction, psychological dependence, tolerance, and physiologic dependence.

Explain the dynamics of enabling and codependency.

Articulate the difference between alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse.

Recognize the more common physiologic effects of alcoholism.

Identify the common medical problems associated with illicit abuse of substances (drugs).

State the rationale for the use of substance-abuse screening tools during the initial assessment of a client with a substance-related disorder.

Articulate the rationale for the use of the Stages of Change Model when planning interventions for a client with a substance-related disorder.

Describe the treatment measures, including nursing interventions, for a client with a substance-related disorder.

Formulate a list of nursing interventions for a client with clinical symptoms of acute substance intoxication.

Develop a list of services available to clients who abuse substances.

Key Terms

Addiction

Addictions nursing

Addictive personality

Alcohol intoxication

Alcohol withdrawal

Aversion therapy

Behavioral dependence

Codependency

Delirium tremens

Detoxification

Drug dependence

Enabling

Habituation

Impaired nurse

Intervention

Korsakoff’s psychosis

Physiologic dependence

Psychological dependence

Stages of Change Model

Substance use

Tolerance

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Substance-related disorders refers to the use and abuse of alcohol, illicit drugs, or substances such as over-the-counter (OTC) or prescription drugs. When substance use creates difficulties for the user or ceases to be entirely volitional, it becomes the concern of all the helping professions, including nursing. This chapter discusses the history of substance use and abuse; describes the terminology, epidemiology, clinical symptoms, and diagnostic characteristics of the major substance-related disorders; and focuses on the application of the nursing process as the nurse provides care for a client diagnosed with a substance-related disorder.

History of Substance Use and Abuse

Individuals have used and abused various substances to achieve desired mood states or as defense mechanisms to deal with reality. Following is a brief discussion of the limited information that is available regarding the history of the origin of substance use and abuse.

History of Drug Use and Abuse

According to a Chinese medical compendium dated from 2737 BC, the Chinese were the first to use marijuana to achieve euphoria. As early as the year 2000 BC, the Greeks used opium, and the Aztecs incorporated hallucinogens into religious rituals. During the Middle Ages (400 to 1500), witches brewed potent concoctions, and New World merchants transported opium along with slaves and rum. The use and abuse of several substances increased during the Civil War period (1861–1865), when soldiers became addicted to prescription drugs that were used to alleviate pain in the battlefield. Cocaine was introduced as a miracle drug and used in patent medicine. Heroin was also produced and sold by traveling salesmen; however, the addictive potential limited the use of these drugs by society. Marijuana was openly used until the federal government discouraged its use in 1930. The recreational use of illicit drugs resurfaced between 1950 and 1960. Cocaine, which was popular during the 1970s, became available as “crack cocaine” in the 1980s. During the 1990s, the use of heroin and smoking of marijuana regained popularity. Since that time, several forms of illicit drugs (eg, methamphetamine, designer drugs, anabolic steroids) have become more commonplace in society than ever before. Drug use and abuse continues to be a significant public health problem despite public outcry and regulation by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) (Goulding & Shank, 2005).

History of Use and Abuse of Alcohol

There was a time when the sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages was illegal in the United States. Alcohol was first introduced in the U.S. by the Puritans around 1620. The use of alcohol reflected their religious belief that drinking was a natural and normal part of life. Alcohol was also an effective analgesic, and generally enhanced the quality of life. People of both sexes and all ages typically drank beer with their meals. By 1697, distilleries were used to make rum, wine, beer, and cider.

In 1784, Benjamin Rush, a physician, argued that excessive use of alcohol caused injury to physical and psychological health. Followers of Rush formed a temperance movement in 1789 as an organized effort to encourage moderation or complete abstinence in the consumption of intoxicating liquors. Drinking had become an activity associated with masculine aggression and antisocial behavior. In fact, alcohol was blamed for many of society’s problems, among them severe health issues, destitution and crime. The movement’s ranks were mostly filled by women who, with their children, had endured the effects of unbridled drinking by many of the men in their lives. By 1826, the American Temperance Society was organized with a mission to educate individuals about the effects of drinking on religion and morality. Antialcohol education was introduced in the schools between 1901 and 1902. On January 16, 1920, prohibition of the sale and consumption of alcohol became a law. Speakeasies soon flourished across the country and there were underground saloons. Prohibition spawned organized crime, bootlegging, and corruption, and, by the late 1920s, prohibition became a very unpopular reality. Democrats used prohibition as an issue during the 1932 presidential campaign. In February of 1933, Congress passed the 21st amendment to repeal prohibition. Unfortunately, statistics kept by the Center for Disease Control indicate

the use and abuse of alcoholism continues to have an adverse effect on society (eg, motor vehicle accidents, various medical problems, depression, suicide) (Essortment.com, 2006; Hanson, 2006).

the use and abuse of alcoholism continues to have an adverse effect on society (eg, motor vehicle accidents, various medical problems, depression, suicide) (Essortment.com, 2006; Hanson, 2006).

According to the 2004 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, an annual survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States age 12 years or older, 22.5 million Americans (or 9.4% of the population) were classified as having past-year substance dependence or abuse, about the same number as in 2002 and 2003. Alcohol- and drug-related use or abuse problems continue to contribute to enormous damage to society, and the magnitude of these costs underscores the need to find better ways to prevent and treat these disorders. The rising costs from substance-related public health issues warrant a major and continuous investment in research on prevention and treatment (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2005).

Overview of Substance-Related Disorders

Terminology Associated With Substance-Related Disorders

Substance use is simply the ingestion of a chemically active agent such as OTC medication, a prescribed drug, or illicit drug, alcohol, or nicotine. Addiction has been defined as an illness characterized by “compulsion, loss of control, and continued patterns of abuse despite perceived negative consequences; obsession with a dysfunctional habit” (American Nurses Association [ANA], Drug and Alcohol Nursing Association, & National Nurses Society on Addictions [NNSA], 1987). Addiction is a term used to define a state of chronic or recurrent drug intoxication, characterized by psychological and physical dependence as well as tolerance. Habituation, also referred to as psychological dependence, is a term used to describe a continuous or intermittent craving for a substance to avoid a dysphoric or unpleasant mood state. Habituation implies an emotional dependence on a drug or a desire or compulsion to continue taking a drug. Tolerance refers to the person’s ability to obtain a desired effect from a specific dose of a drug. For example, as a person develops a tolerance for 10 milligrams of diazepam (Valium), she or he increases the dose to 15 or 20 milligrams to achieve the desired effects originally experienced at the 10-milligram dose. Physiologic dependence refers to the physical effects resulting from the multiple episodes of substance use; it is manifested by the appearance of withdrawal symptoms after the person stops taking a specific drug. Behavioral dependence refers to the substance-seeking activities and pathological use patterns of the person using the substance. Behavioral dependence is often associated with social activities. For example, an individual may exhibit the behavioral dependence of smoking marijuana or using other illicit substances while watching television or attending sports activities with one’s peers. Codependency is a term that refers to all the behavioral patterns of family members who have been significantly affected by another family member’s substance use or abuse. Family members may feel the substance-using behavior of the user is voluntary and willful and that the user cares more for the substance than for them. They often experience feelings of anger, rejection, denial, failure, guilt, or depression and shift the blame for the user’s behavior onto other family members. Such behavior by family members actually perpetuates the user’s dependence and is referred to as enabling (Sadock & Sadock, 2003; Shahrokh & Hales, 2003).

In 1964, the World Health Organization (WHO) suggested substituting the term drug dependence for “addiction” to better describe the two concepts of dependence: behavioral dependence and physiologic dependence. In addition, the word “substance” is used in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) because “drug” implies a manufactured chemical, whereas many substances associated with abuse patterns occur naturally (eg, marijuana) or are not meant for human consumption (eg, glue) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

According to the WHO, the words “addict” and “addiction” ignore the concept of drug abuse as a medical disorder. However, a recent literature search noted that several disciplines, including nursing and the medical profession, continue to use the word “addiction” interchangeably with “drug dependence” and “abuse.”

Epidemiology of Substance-Related Disorders

Globally, alcohol consumption has increased in recent decades, with all or most of that increase in developing countries. This increase is often occurring in countries with few methods of prevention, control or

treatment. The illicit use of drugs has also taken on global dimensions. There is sufficient reason to believe that unregulated excessive drug supply and consumption trends in some countries may be continuing and new problems may be developing (World Health Organization, 2006a, 2006b).

treatment. The illicit use of drugs has also taken on global dimensions. There is sufficient reason to believe that unregulated excessive drug supply and consumption trends in some countries may be continuing and new problems may be developing (World Health Organization, 2006a, 2006b).

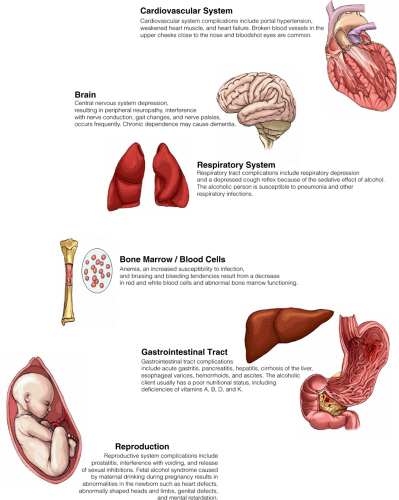

Substance-related disorders are responsible for dysfunctional marital and family relationships, divorce, desertion, child abuse, displaced children, and impoverished families. Alcohol-related medical problems can be disabling, chronic, or fatal (Figure 25-1). Fetal alcohol syndrome is one of the leading causes of birth defects in the United States. Clients who abuse alcohol or drugs may develop comorbid conditions such as alcohol- or substance-induced mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and dementia. A discussion of the epidemiology of substance-related disorders follows.

Alcohol Use and Abuse

Agencies such as the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and National Clearinghouse for Alcohol and Drug Information (NCADI) conduct periodic surveys on the use and abuse of alcohol in the United States. Several factors are considered during the surveys, including race and ethnicity, gender, region and urbanicity, education, and socioeconomic class (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). A summary of the most recent surveys regarding the use and abuse of alcohol follows.

NCADI and NIAAA Surveys

According to the 2003 statistics, approximately 90% of all U.S. residents have had an alcohol-containing drink at least once in their lives, and about 51% of all U.S. adults currently use alcohol. Most people engage in the reasonable and responsible use of alcohol; however, the 2003 statistics indicate that approximately 15.3 million Americans (one in every 12 adults) abuse alcohol, compared with the 5.1 million persons identified in 1990. About 30% to 56% of all adults in the United States have had at least one episode of an alcohol-related problem. Thirteen percent of men qualify for a diagnosis of current alcohol abuse or dependence, compared with 4% of women. Several million Americans engage in risky drinking patterns that result in serious alcohol-related problems such as traumatic or fatal injuries. For example, during spring break, college students who abuse alcohol have been fatally injured during falls from high places or while diving into pools from hotel balconies. Heavy drinking patterns also result in motor vehicle accidents, burns, severe depression, suicide, or homicide (NCADI, 2003; NIAAA, 2003). See Supporting Evidence for Practice 25-1 for information about mortality and alcohol.

NIDA Survey

Fifty-three percent of the men and women surveyed in the United States reported that one or more close relatives abuse or are dependent on alcohol. Alcohol abuse is present in 3% to 15% of the elderly population, 18% of medical inpatients, and 44% of psychiatric patients. Caucasians have the highest rate of alcohol use (56%). No statistical differences are noted for race or ethnicity with the heavy use of alcohol (5.7% for whites, 6.3% for Hispanics, and 4.6% for African Americans). Approximately 70% of adults with college degrees currently are drinkers, compared with only 40% of those with less than a high school education. These statistics dispel the idea that drinking is often associated with lower educational levels. Individuals with a college education may use alcohol to reduce stress or to socialize (NIDA, 2003; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Abuse of alcohol also is a major health problem for older children and adolescents. Approximately 28% of high school seniors and 41% of persons in the 21- to 22-year-old age group engage in binge drinking. Heavy drinking by adolescents is associated with emotional and behavioral problems. Data show that adolescents who drink heavily also skip school, use illicit drugs, steal from others, feel sad and depressed, run away from home, and try to injure themselves or commit suicide more often than their non-drinking counterparts (Clinical Psychiatry News, 2000).

Illicit Drug or Substance Use and Abuse

The more commonly abused illicit drugs today are cocaine, marijuana, inhalants, and heroin. Statistics regarding illicit drug or substance use and abuse are available through various agencies including the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) that replaced the annual National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) in 2002; the NIDA; and the DEA. A summary of their latest reports follows.

NSDUH Survey

According to the NSDUH (2004) survey, more than 11.1 million people aged 12 or older (or 4.6% of the population) have used 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; ecstasy). Between

2003 and 2004, the number of current users of MDMA decreased from 470,000 to 450,000 (0.2% of the population in both years). NSDUH also reported that 11.7 million people (or 4.9% of the population) used methamphetamine at least once during their lifetime. The number of current users of methamphetamine decreased from 607,000 (or 0.3% of the population) in 2003 to 583,000 (or 0.2% of the population) in 2004.

2003 and 2004, the number of current users of MDMA decreased from 470,000 to 450,000 (0.2% of the population in both years). NSDUH also reported that 11.7 million people (or 4.9% of the population) used methamphetamine at least once during their lifetime. The number of current users of methamphetamine decreased from 607,000 (or 0.3% of the population) in 2003 to 583,000 (or 0.2% of the population) in 2004.

Supporting Evidence for Practice 25.1: The Relationship Between Alcoholism and Mortality in White Males

Problem under Investigation

What is the relative risk of mortality among white male problem drinkers?

Summary of Research

Subjects were 1,853 white male problem drinkers aged 18 to 79 years who received treatment for alcohol-related problems at community mental health centers in the state of Vermont in 1991. Comparison group data were derived from the state vital records database. Researchers concluded that participation in treatment programs was highest for subjects aged 18–29 years, followed by subjects who were aged 30–49 years. Problem drinkers who were aged 18–29 years were 4.3 times as likely to die during the study compared with the general population of the same age group; problem drinkers aged 30–49 years were 2.5 times as likely to die compared with the general population of the same group; and problem drinkers over the age of 50 years were 1.5 times as likely to die than the general population of men in the same age category.

Support for Practice

The psychiatric–mental health nurse should assess for alcohol-related problems during each visit by children, adolescents, and adults, regardless of presenting complaints. Client education should include a discussion of the risks of increased mortality when abusing alcohol.

Source:

Banks, S. M., Pandiani, J. A., Schacht, L. M., & Gauvin, L. M. (2000). Age and mortality among white male problem drinkers. Addiction, 95 (8), 1249–1254.

NIDA Survey

Among students surveyed by NIDA (2004), 16.6% of eighth graders (compared with 23% in 2002), 31.2% of tenth graders (compared with 41% in 2002), and 47.9% of twelfth graders (compared with 59% in 2002) reported that “club drugs” (eg, MDMA, methamphetamine, ketamine, flunitrazepam [Rohypnol], gamma-hydroxybutyrate [GHB]) were easy or very easy to obtain.

The majority of illicit substance users are white, non-Hispanic persons (74%). Men (8.5%) have a higher rate of illicit drug use than women (4.5%). The highest rates of drug abuse were found among young people ages 16 to 17 years (19.2%), compared with ages 18 to 20 years (17.3%). Only about 1% of people age 50 years and older reported using illicit drugs (NIDA, 2004).

Most illicit substance users begin to use and abuse substances when they are young. The development of addiction is rare after young adulthood. Mortality among young users is high; however, with improved medical management of various diseases, it is expected that during the coming decades, larger proportions of young-adult substance abusers will survive into old age (NIDA, 2004).

DEA Survey

According to estimates from the DEA survey, prescription medication abuse accounts for nearly 30% of the nation’s drug problem. Addiction disorders affect 20% to 50% of hospitalized clients; 15% to 30% of clients in primary care settings; and as many as 50% of clients with a psychiatric illness. Moreover, approximately 72% of clients with an addiction disorder are believed to have a comorbid psychiatric diagnosis (DEA, 2006).

Hydrocodone (Vicodin, Lortab) continues to be the most widely abused prescribed medication in the U.S. Other potentially addictive medications that are not specifically regulated include carisoprodol (Soma); tramadol (Ultram); and dextromethorphan (DXM), a cough suppressant in OTC cough syrups. Attracted by easy availability, teenagers and young adults are increasingly abusing DXM, which, when taken at higher than prescribed doses, can cause euphoria and psychotic symptoms (DEA, 2006; Finn, 2004).

Approximately 80% of benzodiazepine abuse occurs in conjunction with opioids and/or alcohol. Name recognition makes trade name prescription drugs more attractive than their generic equivalents and medications in capsules are more desirable because they can be altered easily (Roscoe, 2004).

Specialty Practice: Addictions Nursing Practice

In the 1970s and 1980s, the care of clients with substance-related disorders became recognized as a unique nursing practice field. The International Nurses Society on Addictions (IntNSA) is a professional specialty organization founded in 1975 for nurses committed to the prevention, intervention, treatment, and management of addictive disorders including alcohol and other drug dependencies, nicotine dependencies, eating disorders, dual and multiple diagnosis, and process addictions such as gambling. IntNSA’s mission is to advance excellence in addictions nursing practice through advocacy, collaboration, education, research and policy development (IntNSA, 2006).

In 1987, the publication The Care of Clients With Addictions: Dimensions of Addictions Nursing Practice described the dimensions of nursing practice associated with substance-related disorders as including the care of clients with a broad range of abuse and addiction patterns (ANA, Drug and Alcohol Nursing Association, & NNSA, 1987). Addictions nursing was defined as an area of specialty practice concerned with care related to dysfunctional patterns of human response that have one or more of the following key characteristics: some loss of self-control capacity, episodic or continuous maladaptive behavior or abuse of some substance, and development of dependence patterns of a physical and/or psychological nature. The addictions nurse addresses needs at every point on the health–illness continuum, uses skills from a number of nursing specialties, and collaborates with professionals in medicine, psychology, social work, and other disciplines. The recognition of addictions nursing as a distinct practice area led to the development of Standards of Addictions Nursing Practice With Selected Diagnoses and Criteria, published in 1988 (ANA & NNSA).

Etiology of Substance- Related Disorders

Several theories describe the onset of substance-related disorders. A brief summary of the more common theories as well as the disease concept of alcoholism follows.

Biologic Theories

The discovery that all drugs of abuse have one thing in common—namely, the stimulation of dopamine secretion—occurred in the 1980s. With scientific innovations, studies have identified the neural structures and pathways responsible for pleasure and reinforcement of behavior. For example, researchers have discovered that the brains of addicts have fewer dopamine D2 receptors in several regions of their brains than do the brains of control subjects. Addictive drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and alcoholism capture these receptor sites and pathways or neural circuits and subvert normal functions (Yasgur, 2004). For instance, cocaine blocks the mechanism by which dopamine is reabsorbed into the cells that release dopamine. Amphetamines provoke the release of dopamine. Nicotine acts on a receptor for the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, possibly preventing the enzyme mono-amine oxidase from breaking up the dopamine molecule. Opiates act at receptor sites for the brain’s own morphine-like substances. Sedative-hypnotics, alcohol, barbiturates, and benzodiazepines act in various parts of the brain on neurons that release γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which directs neurons to stop firing. Consequently, alcohol and drugs can change the way individuals feel and cause them to want to take these substances more often (Grinspoon, 1998a; Smith, 1999).

Researchers have also speculated that some individuals have a predisposition to or are at risk for addiction due to a high level of stress hormones, a deficit in dopamine function that is temporarily corrected by their drug of choice, or the presence of electrical phenomena in the brains of people at risk for alcoholism (Grinspoon, 1998b).

Genetic Theories

Separate studies of twins, adoptees, and siblings indicate that the cause of alcohol abuse has a genetic component. According to Grinspoon, “Individual differences in sensitivity to the addictive powers of drugs are almost certainly strongly influenced by genetics” (1998b, p. 1). Jellinek (1977, 1988) theorized that some individuals have a predisposition to alcoholism as a result of the “loss of control” over alcohol. His theory was supported by comparing data from studies of twins living with their biologic parents to data from studies of twins born to alcoholic parents, but separated after birth and raised by nonalcoholic foster parents. The data indicated that children born to alcoholic parents are particularly susceptible to becoming alcoholic (Goodwin, 1992, 1979). Additional studies with less conclusive data show that other types of substance-related

disorders may be caused by a genetic component (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

disorders may be caused by a genetic component (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Behavioral and Learning Theories

Behavioral theorists believe that addiction results from the positive effect of mood alterations and reduction in feelings of fear and anxiety that one experiences using drugs or alcohol. Additionally, several types of learning are thought to be associated with compulsive self-administration of drugs.

Associative learning is exhibited during relapses experienced among clients addicted to psychostimulants. The brain is specifically designed to absorb and respond in very powerful ways to environmental cues and contexts. Nothing could be more specific, or powerful, than large doses of mind-altering drugs. The brain stores discrete patterns of information related to specific drug usage and produces context-independent sensitization of the organism to the drug or a general lethargy and unresponsiveness to the environment. The response depends on the individual’s choice of substance (Medina, 2000).

Sociocultural Theories

The potential for addiction is affected by economic conditions, formal and informal social controls, cultural and ethnic traditions (eg, Asians and conservative Protestants use alcohol less frequently than do liberal Protestants and Catholics), and the companionship and approval of other drug users (Grinspoon, 1998b; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Additionally, a drug must be available in sufficient amounts to sustain addiction. For example, college dormitories and military bases are two social settings in which excessive and frequent drinking are often considered normal and socially expected. People risk addiction when they lack other capacities, choices, interest, or sources of attachment to something outside themselves.

Teenagers are at risk for alcohol abuse because it is the drug of choice among most adults, it is legal, and it is socially acceptable. Parents indirectly sanction the use of alcohol by drinking in front of their children and telling them that alcoholic beverages are acceptable if drunk in moderation.

Teenagers who possess more leisure time and money and experience less parental or community supervision are at risk for substance abuse, especially when they attend weekend or all-night parties. Drugs are available “everywhere,” according to grade-school children. OTC drugs, prescriptions readily obtained for insomnia, and pain-relief medication used by parents all make substance abuse easy for children and teenagers.

Peers and their values are particularly strong influences. Experimentation, curiosity, rebellion, and boredom are just a few reasons cited by adolescents when asked why they use or abuse drugs (National Criminal Justice Reference Service [NCJRS], 2004a).

Psychodynamic Theories

Although a particular addictive personality has not been identified, many theorists consider individuals who abuse substances to be fixed at an oral or infantile level of development. The abuser searches for immediate gratification of needs, or ways to escape tension, turning to alcohol or drugs to experience euphoria or oblivion. Characteristics frequently seen include low self-esteem, feelings of dependency, low tolerance for frustration and anxiety, antisocial behavior, and fear. Theorists are not certain whether these characteristics were present before the addictive behavior or whether the characteristics are a result of substance or alcohol abuse (Berman, 2001; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Other theorists believe that early childhood rejection, overprotection, or undue responsibility can cause an individual to become dependent on alcohol or drugs to cope with increased anxiety, depression, social or sexual inadequacy, increased social pressures, self-destructive behavior, or due to a desire to lower one’s inhibitions (Berman, 2001).

Disease Concept of Alcoholism

The American Medical Association and the U.S. Public Health Service consider alcoholism to be a disease. Most authorities in the field of alcohol abuse base their beliefs on the pioneering work of Jellinek (1988). He surveyed 2,000 alcoholic men and classified alcoholics into five types. He also identified four progressive phases that the alcoholic experiences.

Alcohol is known to shorten an individual’s life span by 12 to 15 years unless treatment is received. Like other chronic illnesses, it has certain observable symptoms. For example, tolerance occurs as the individual drinks more with less effect. Withdrawal occurs when an individual abruptly stops drinking after alcohol has become a necessity of life to maintain functioning. Finally, alcoholism can be fatal.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Alcohol-Related Disorders

Alcohol (eg, beer, wine, whiskey) is considered a central nervous system (CNS) depressant that causes false self-confidence, false sense of belonging, and lowering of inhibition. Figure 25-1, mentioned earlier in the chapter, depicts the potential medical problems related to the use or abuse of alcohol. Individuals who are dependent on or who abuse alcohol often exhibit impairments in judgment, orientation, memory, affect, cognition, speech, and mobility, as well as behavioral changes.

Two categories of alcohol-related disorders are included in this classification. The first, alcohol use disorders, includes alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse. The second, alcohol-induced disorders, includes 12 subtypes:

Alcohol intoxication

Alcohol withdrawal

Alcohol intoxication delirium

Alcohol withdrawal delirium

Alcohol-induced persisting dementia

Alcohol-induced persisting amnestic disorder

Alcohol-induced psychotic disorder

Alcohol-induced mood disorder

Alcohol-induced anxiety disorder

Alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction

Alcohol-induced sleep disorder

Alcohol-related disorder, not otherwise specified

Both alcohol use disorders are discussed in the sections that follow; selected alcohol-induced disorders are also discussed.

Alcohol Use Disorders

Patterns of alcohol use disorders include alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse. An understanding of these patterns is essential for psychiatric–mental health nursing practice.

Alcohol Dependence

Alcohol dependence is characterized by tolerance to alcohol or by the development of withdrawal phenomena upon cessation of or reduction in intake (Shahkroh & Hales, 2003). Alcohol dependence and alcohol abuse (see discussion that follows) share features with other substance-dependence and -abuse disorders such as those associated with sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics.

The essential feature of alcohol dependence is a cluster of cognitive, behavioral, and physiologic symptoms indicating that the individual continues use of the alcohol despite critical alcohol-related problems. There is a maladaptive pattern of alcohol use resulting in distress as the individual experiences a cluster of three or more of seven stated symptoms during a 12-month period:

Tolerance, defined as a need for markedly increased amounts of alcohol to achieve desired effect or a markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of alcohol

Withdrawal symptoms or the continued use of alcohol to relieve or avoid withdrawal symptoms

Intake of alcohol in larger amounts or over a longer period of time than that which was intended

Persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control use of alcohol

A significant amount of time spent in activities necessary to obtain alcohol, drink alcohol, or recover from its effects

Social, occupational, or recreational activities given up or reduced because of drinking alcohol

Continued drinking of alcohol despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by alcohol

The DSM-IV-TR also lists specifiers to accompany the diagnosis. These include with physiologic dependence (evidence of tolerance or withdrawal) or without physiologic dependence (no evidence of withdrawal or tolerance).

Alcohol Abuse Disorder

The criteria for alcohol abuse disorder do not include tolerance, withdrawal, or a pattern of compulsive use. The individual exhibits one or more of the following symptoms in a 12-month period:

Recurrent drinking of alcohol resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home

Recurrent drinking in situations in which it is physically hazardous

Recurrent alcohol-related legal problems

Continued use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused by alcoholism

Alcohol-Induced Disorders

Alcohol-induced disorders are the result of the effects of alcohol on the CNS. Clients with alcohol-induced disorders exhibit impairment of neurologic functioning such as delirium or dementia. They also may exhibit behavioral changes.

Alcohol Intoxication

Alcohol intoxication occurs after the recent ingestion of alcohol and is evidenced by behavioral changes such as decreased inhibition, impaired social or occupational functioning, fighting, or impaired judgment. The client may exhibit mood changes, increased verbalization, impaired attention span, or irritability. Other symptoms include slurred speech, disorientation, facial flushing, lack of coordination, unsteady gait, nystagmus, impaired memory, disorientation, and stupor or coma.

Alcohol Withdrawal

Clients generally experience clinical symptoms of alcohol withdrawal within several hours to a few days after the cessation or reduction of heavy and prolonged alcohol consumption. The client may experience symptoms such as autonomic hyperactivity; increased hand tremor; sleep disturbances, insomnia, or nightmares; nausea or vomiting; transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations or illusions; delusions, psychomotor agitation; anxiety; and grand mal seizures. Increased blood pressure may occur. Elevated temperatures in excess of 100°F (37.3°C) and pulse in excess of 100 beats per minute may indicate impending alcohol withdrawal delirium.

Alcohol Withdrawal Delirium

Alcohol withdrawal delirium, also referred to as delirium tremens, may occur from 24 to 72 hours after the client’s last drink. Elevation of vital signs accompanies restlessness, tremulousness, agitation, and hyperalertness. Any noises or quick movements are perceived as greatly exaggerated, shadows are misinterpreted, and illusions and hallucinations frequently occur. The client’s speech is incoherent. Serious medical complications may occur if the client is left untreated.

Alcoholic-Induced Persisting Dementia

Individuals who experience a prolonged, chronic dependence on alcohol may develop alcoholic-induced persisting dementia. Clinical symptoms include a severe loss of intellectual ability that interferes with social or occupational functioning and impaired memory, judgment, and abstract thinking. Permanent brain damage can occur in severe cases.

Alcoholic-Induced Persisting Amnestic Disorder

Individuals who drink large amounts of alcohol over a prolonged period often have poor nutritional habits. Two CNS disorders are associated with alcoholism. The first, Korsakoff’s psychosis, is a form of amnesia characterized by a loss of short-term memory and the inability to learn new skills. Clinical symptoms include disorientation and the use of confabulation. Degenerative changes in the thalamus occur because of a deficiency of B-complex vitamins, especially thiamine and B12. The second disorder is Wernicke’s encephalopathy, an inflammatory hemorrhagic, degenerative condition of the brain caused by a thiamine deficiency. Lesions occur in the hypothalamus, mamillary bodies, and tissues surrounding ventricles and aqueducts. Clinical symptoms include double vision, involuntary and rapid eye movements, lack of muscular coordination, and decreased mental function, which may be mild or severe.

Other Alcohol-Induced Disorders

Individuals who abuse alcohol can develop depression, anxiety, sexual dysfunction, and sleep disorders. Clinical symptoms of anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders were discussed in earlier chapters. Sexual disorders are discussed in Chapter 26.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics of Other Substance-Related Disorders

Ten classes of substances, other than alcohol, are associated with both abuse and dependence: amphetamines,

caffeine, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine (PCP), and the group of sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics.

caffeine, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, nicotine, opioids, phencyclidine (PCP), and the group of sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics.

A diagnosis of multiple-substance or polysubstance abuse occurs when people mix drugs and alcohol. The severity of psychoactive substance dependence is classified according to the following criteria: mild, moderate, severe, in partial remission, or in full remission.

Sedative-, Hypnotic-, or Anxiolytic-Related Disorders

Substances included in the category of sedatives, hypnotics, and anxiolytics include benzodiazepines, carbamates, barbiturates, barbiturate-like hypnotics, all prescription sleeping medications, and all anxiolytic medications except the nonbenzodiazepine antianxiety agents (eg, buspirone). Ingestion of these drugs in high doses can be lethal, especially when they are mixed with alcohol.

Taken orally or intravenously, these drugs are used to relax the CNS or slow down body processes. They temporarily ease tension and induce sleep. Medically, they may be used in the treatment of hypertension, peptic ulcers, or seizures; as a relaxant before and during surgery; and as a sedative for use in mental and physical illness.

Normal effects of these drugs include a decrease in cardiac and respiratory rate, lowered blood pressure, and a mild depressant action on nerves, skeletal muscles, and the heart. Overdoses or intoxication may result in symptoms such as slurred speech, incoordination, drunken appearance, staggering gait, nystagmus, impaired memory, stupor, or coma. Other symptoms may include poor judgment, mood swings, paranoia, lack of sexual inhibition, and aggressive impulses. Medical symptoms include dry mouth, headaches, dizziness, chills, and diarrhea (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Street names for these drugs include “libs,” “blues,” “rainbows,” “yellow-jackets,” and “downers.” Barbiturates are the leading cause of accidental poisoning, as well as a primary method of committing suicide. Barbiturate dependency is one of the most difficult disorders to cure. Clinical symptoms of sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic withdrawal may include diaphoresis, increased pulse rate (greater than 100 beats per minute), hand tremors, nausea and vomiting, insomnia, transient hallucinations or illusions, psychomotor agitation, and anxiety (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Opioid-Related Disorders

An opioid is a drug or naturally occurring substance that resembles opium or one or more of its alkaloid derivatives. Opiates are powerful drugs derived from the poppy plant that have been used for centuries to relieve pain. The opioid classification includes natural opioids such as morphine, semi-synthetics such as heroin, and synthetics with morphine-like action such as codeine or methadone. Medications such as pentazocine, which has both opiate agonist and antagonist effects, are also included in this classification.

Opioids are narcotic drugs that induce sleep, suppress coughing, and alleviate pain. People abuse opiates by taking them orally, inhaling them (eg, snorting or smoking), or injecting them into their veins in an attempt to help relieve withdrawal symptoms, for “kicks,” or to “feel good.” The user becomes passive and listless as the opioids depress the respiratory center of the brain, causing shallow respirations. The person also experiences reduced feelings of hunger, thirst, pain, and sexual desire. As the effects of the drug wear off, the user, who becomes physically and emotionally addicted by requiring increasingly larger dosages, suffers withdrawal symptoms unless another dose of the drug is taken.

Opioids, also referred to as “white stuff,” “hard stuff,” and “junk,” are considered to be the most addictive drugs. Acute overdose or intoxication is identified by symptoms of drowsiness; slurred speech; decreased, slow respirations; constricted pupils; and a rapid, weak pulse. The client also may exhibit mood swings, psychomotor agitation or retardation, impaired judgment, or impaired social or occupational functioning (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Opioid withdrawal symptoms begin 12 to 16 hours after the last dose and are characterized by watery eyes, rhinitis, yawning, sneezing, and diaphoresis. Other symptoms include dilated pupils, restlessness and tremors, goose bumps, irritability, loss of appetite, muscle cramps, nausea and vomiting, fever, and diarrhea. Symptoms subside in 5 to 10 days if no treatment occurs (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Amphetamine-Related Disorders

Amphetamines or amphetamine-like substances are medically indicated for the treatment of attention-deficit–hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, weight reduction, and treatment-resistant depression. Amphetamines (“pep pills”) are drugs that directly stimulate

the CNS and create a feeling of alertness and self-confidence in the user. They are also referred to by drug abusers as “wake-ups,” “speed,” “eye-openers,” “co-pilots,” “truck drivers,” “uppers,” or “bennies.”

the CNS and create a feeling of alertness and self-confidence in the user. They are also referred to by drug abusers as “wake-ups,” “speed,” “eye-openers,” “co-pilots,” “truck drivers,” “uppers,” or “bennies.”

These drugs are often abused by oral ingestion, injection into veins, smoking, or inhalation of large doses to obtain an exaggerated effect of the stimulating action. People also take these drugs for kicks, for thrills, or to combat boredom; to stay awake or to allow greater physical effort; or to counteract the effects of alcohol and barbiturates. Amphetamines are considered to be dangerous because they can drive a user to do things beyond his or her physical limits; they can cause mental fatigue, dizziness, and feelings of fear and confusion; and sudden withdrawal can lead to depression and suicide. The heart and circulatory system also may be damaged from the adverse effects of adrenaline overproduction due to drug abuse.

Clinical symptoms of intoxication include tachycardia or bradycardia, alterations in blood pressure, cardiac arrhythmias, respiratory depression, pupillary dilation, excitability, tremors of the hands, increased talkativeness, profuse diaphoresis, dry mouth, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, headaches, pallor, diarrhea, and unclear speech (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). The abuser can develop a psychological dependence on stimulants and may experience delusions, auditory and visual hallucinations, or a drug psychosis that resembles schizophrenia. Clinical symptoms of withdrawal include dysphoria, fatigue, altered sleep patterns, increased appetite, dreams, and psychomotor agitation or retardation (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Cocaine-Related Disorders

Cocaine is a short-acting CNS stimulant substance that is extracted from the leaves of the South American coca plant (Erythroxylon coca). Historically, the leaves of the plant were chewed for refreshment, and were used by peasant laborers to relieve fatigue and fight off pain or hunger. Cocaine also produces feelings of happiness, alertness, sensory awareness, and enhances one’s self-esteem.

Cocaine is available as a white crystalline powder or in larger pieces referred to as “rocks.” Powdered cocaine is usually sniffed, snorted, smoked in a pipe (freebasing), or injected into a vein or subcutaneous tissue.

Physical effects of cocaine intoxication include immediate dilation of the pupils and an increase or decrease in blood pressure, pulse, respirations, and body temperature. Users may also experience a loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, weight loss, insomnia, impaired thinking, agitation, seizures, chest pain, or coma (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Long-term effects include chronic nose bleed, runny nose, chronic sore throat, exhaustion, respiratory ailments, vitamin deficiencies, dangerous weight loss, and miscarriage/birth defects.

Clients who experience cocaine withdrawal may exhibit fatigue, an increased appetite, altered sleep patterns, and behavioral changes such as agitation or psychomotor retardation. Panic attacks or cocaine psychosis may occur. Individuals with a history of cardiac disease may experience chest pain, heart attack, or heart failure. Cocaine also can cause sudden heart attack in healthy young people (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Cannabis-Related Disorders

Marijuana is a common plant with the biologic name of Cannabis sativa. With the ability to act as a stimulant or depressant, it is often considered to be a mild hallucinogen with some sedative properties. As of February 2005, 12 states have legalized the use of marijuana to alleviate the symptoms of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, stimulate appetite in clients with HIV/AIDS, and lower ocular pressure in clients with glaucoma: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Washington (DEA, 2006). With written certification from a physician, clients or their caregivers are able to register with a state to grow and use marijuana. The physician, client, and caregiver are all protected from arrest and prosecution.

When used illegally, marijuana is often combined with other addictive substances such as alcohol or nicotine. Most users in the 18- to 25-year-old age range are male. Many people who try marijuana go on to use it extensively, and many of these people use it in combination with other substances such as opioids, PCP, or hallucinogens (APA, 2000; Pfizer, Inc., 1996).

Persons who use marijuana usually smoke it in a pipe or as a rolled cigarette (“joint”). Individuals also may take it orally as capsules or tablets, on sugar cubes, or in food. Holders (“roach clips”) are used to get the last puffs from marijuana cigarette butts when they become too short to handle with fingers. Slang names for marijuana include “pot,” “herb,” “grass,” “weed,” “smoke,” and “Mary Jane.”

Marijuana acts quickly, in approximately 15 minutes, after it enters the bloodstream, and its effects last

approximately 2 to 4 hours. It affects a person’s mood, thinking, behavior, and judgment in different ways, and in large doses it can cause hallucinations.

approximately 2 to 4 hours. It affects a person’s mood, thinking, behavior, and judgment in different ways, and in large doses it can cause hallucinations.

General physiologic symptoms of intoxication include increased appetite, lowered body temperature, depression, drowsiness, unsteady gait, inability to think clearly, excitement, reduced coordination and reflexes, and impaired judgment. Users of large amounts may experience suicidal ideation or have delusions of invulnerability, causing them to take risks.

Although marijuana is not considered to be physically addicting and no withdrawal criteria have been established, it may lead to psychological dependence, thereby retarding personality growth and adjustment to adulthood. Its use also can expose the user to those using and pushing stronger drugs (APA, 2000).

Hallucinogen- and Phencyclidine-Related Disorders

Hallucinogens and PCP are associated only with abuse because physiologic dependence has not been demonstrated. They are referred to as “mind benders” or psychedelic drugs, affecting the mind and causing changes in perception and consciousness.

Hallucinogens

Examples of hallucinogens include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), mescaline, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 2,5 dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine (STP), and psilocybin.They may be taken orally or injected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access