Clients Coping With Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

Although the central feature of HIV infection involves collapse of the body’s ability to mount an appropriate cell-mediated immune response with attendant medical complications, neuropsychiatric phenomena can also be prominent.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Explain the etiology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Identify those groups of individuals at risk for AIDS.

Compare and contrast the following disease processes associated with AIDS: AIDS-related complex, secondary infectious diseases, and neuropsychiatric syndromes.

Describe the psychosocial impact of AIDS.

Discuss the effects of AIDS on family dynamics.

Recognize the clinical phenomena of each of the three phases of AIDS.

Formulate a plan of care for a client exhibiting clinical symptoms of the middle stage of AIDS.

Articulate the purpose of including interactive therapies in the plan of care for a client with AIDS.

Outline the types of community services available to provide continuum of care for clients with AIDS.

Key Terms

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

AIDS-related complex (ARC)

Homophobia

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Neuropsychiatric syndromes

Opportunistic infectious diseases

Secondary infectious diseases

Stigmatization

To be effective and provide compassionate care without undue fear or anxiety, health care professionals must be knowledgeable about the transmission, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of individuals who have acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or who are infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; Norman, 2006). AIDS is associated with numerous biopsychosocial complications, secondary infectious diseases, and AIDS-related disorders. The medical conditions (eg, persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, lymphoma, and pneumonia) and neuropsychiatric phenomena (eg, delirium, dementia, depression, and anxiety) associated with HIV-positive status and AIDS are pandemic (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Although neither a cure for the disease nor a preventive vaccine has been developed, therapeutic alternatives are providing benefit to many who are HIV-infected. Much has been learned about the complexities of HIV/AIDS, how to keep clients disease free longer, and how to manage their symptoms more effectively. As a result of these advances, individuals with HIV infection are living longer than before and the progression to AIDS has declined sharply (Norman, 2006; Tucker, 2006). Nurses play a key role in recognizing these conditions. Each of the conditions is usually treated by medication that puts the client at risk for the development of adverse effects on the central nervous system, as well as increases the risk for development of neuropsychiatric disorders.

This chapter focuses on the history, etiology, and epidemiology of AIDS; the clinical symptoms of AIDS, secondary infectious diseases, and AIDS-related disorders; the psychosocial impact of these disorders; and the effects of these disorders on family dynamics. The role of the psychiatric–mental health nurse and application of the nursing process are also discussed.

History and Etiology of HIV/AIDS

Beginning as a benign simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) found in the African chimpanzee population, SIV evolved into a human-killer in the early 1930s, long before it was recognized as a disease. Analysis of a blood sample of a Bantu man who died of an unidentified illness in the Belgian Congo in 1959 made him the first human confirmed case of the SIV infection, later to be identified as HIV infection. The virus stayed in remote Africa until jet travel, big cities, and the sexual revolution spread it worldwide, according to Tanmoy Bhattachary, a researcher at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in Los Alamos, New Mexico (Associated Press, 2000).

In 1978, gay men in the United States and Sweden and heterosexuals in Tanzania and Haiti began to exhibit signs of the SIV infection. Between 1980 and 1983, there were 3,422 deaths in the United States attributed to the virus. During that time, doctors in New York and Los Angeles reported an unusual and deadly form of lung infection (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) and a rare skin cancer (Kaposi’s sarcoma) among young homosexual men. In 1983, researchers at the Pasteur Institute, a private foundation dedicated to the prevention and treatment of diseases through biologic research, identified the cause of these conditions as the lymphadenopathy-associated virus. Referred to as HTLV-III (human T-cell lymphotropic virus), the virus was later renamed the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In 1986, HIV was identified as the virus that causes several conditions we now call acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). In 1988, as an attempt to educate the public about this disease, the U.S. Surgeon General published and mailed a pamphlet, “Understanding AIDS,” to more than a million citizens (Aegis.com, 2006; Avert.org, 2006; Fohn.net, 2006). Extensive research has led to the discovery that human immunodeficiency virus is carried in the blood, blood products, and body fluids such as semen. It is transmitted primarily through intimate sexual contact or through the sharing of needles by intravenous drug users.

Epidemiology

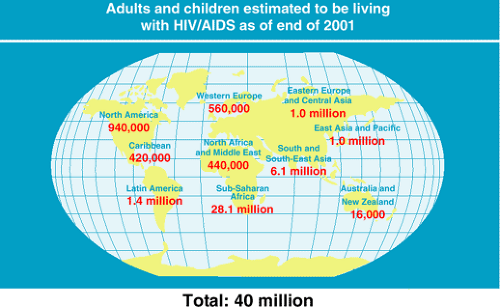

Global statistics, representative of cases in Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America, have remained fairly constant during the years 2001 through 2005. Figure 34-1 depicts the global distribution of HIV/AIDS as of 2001. In the year 2005, there were an estimated 39.4 million people living with HIV/AIDS worldwide compared with 40 million in 2001 (United Nations, 2006). Additionally, 2005 global statistics (MacNeil, 2006; United Nations, 2006) show that:

5 million individuals were infected. Of these 5 million, 2 million were children.

Teenagers accounted for 50% of newly infected cases

46% (or 18 million) to 50% (or 20 million) of infected cases were women and girls

25% to 33% of infected individuals were unaware of their status

3 million HIV/AIDS-related deaths occurred

In the United States, at the beginning of 2004, approximately 1,039,000 to 1,185,000 individuals were infected with HIV, and an estimated 405,925 individuals were living with AIDS. Approximately 25% of those individuals affected were women, compared with 20% in 2001. An estimated 21.8 million deaths have occurred since the first cases of AIDS were identified in 1981 (Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, 2003; United Nations, 2006).

Groups at Risk for AIDS

Approximately 2% to 4% of the U.S. population, or 4 to 5 million people, are at high risk for AIDS because of unsafe sexual practices or injection drug use. Groups at risk for development of AIDS include:

African American and Hispanic populations

Homosexual and bisexual men who do not practice safe sex

Individuals with multiple sexual partners

Adolescents who do not practice safe sex

Heterosexual intravenous drug users

Homosexual and bisexual men who also use intravenous drugs

Heterosexual men and women who have had sex with a person from one of the previously mentioned groups

Persons with hemophilia and others who have received blood transfusions

Infants born to mothers carrying the AIDS virus

Persons who are occupationally exposed (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2001; Davidson, 2004)

AIDS in Adolescents

In some developing countries, as many as 50% of young adults between the ages of 25 and 35 years are infected with the AIDS virus. In the United States, new HIV infections among young people between the ages of 15 and 24 years has been estimated to be 40,000 per year for the last few years. Given the fact that the average time of onset from infection to the development of AIDS is approximately 10 years, these young adults were probably infected as teenagers (CDC, 2000; Weiss, 2001).

Several factors have contributed to the rise of HIV infection in adolescents. Teens who engage in sexual

exploration, including bisexual experimentation, generally have a sense of infallibility, or believe that HIV can be cured. “Russian roulette group sex” is an example of experimentation in which members of the group engage in sex knowing that one person in the group has HIV. The excitement is in the risk of becoming HIV-infected. Furthermore, lack of adequate protection by young teens places girls at high risk because immature cervixes are more likely to submit to infection (Ivantic-Doucette & Haglund, 2004).

exploration, including bisexual experimentation, generally have a sense of infallibility, or believe that HIV can be cured. “Russian roulette group sex” is an example of experimentation in which members of the group engage in sex knowing that one person in the group has HIV. The excitement is in the risk of becoming HIV-infected. Furthermore, lack of adequate protection by young teens places girls at high risk because immature cervixes are more likely to submit to infection (Ivantic-Doucette & Haglund, 2004).

Making decisions about disclosure is difficult for teens, who may lack social experiences and skills. Their fear of the loss of friends, family, and other supports, or lack of knowledge about the phenomena of the illness, often delays them from seeking help (Ferri, 1995; Weiss, 2001).

AIDS in the Older Adult

The number of elderly persons with HIV/AIDS continues to rise. According to the CDC (2000), 11% of all new AIDS cases in the United States occur in people age 50 years and older. In the past, little attention had been given to this group in the areas of prevention, education, psychosocial support or treatment because older people and their health care providers did not consider older adults to be at risk for contracting the AIDS virus. Individuals may live for many years with HIV infection but be asymptomatic. With aging, the immune system weakens, possibly leading to subtle signs of HIV. However, these signs may be attributed to normal physiologic changes during the aging process. Additionally, HIV testing may not be requested because of the belief that HIV infection affects young people or those who abuse substances. Older adults also may be too embarrassed to ask about the possibility of an infection. Consequently, as a result of a delay in the diagnosis of HIV, older adults often present with a more advanced disease process (CDC, 2000; Willard & Dean, 2000; Fox-Seaman, 2005; Norman, 2006).

Clinical Picture Associated With AIDS

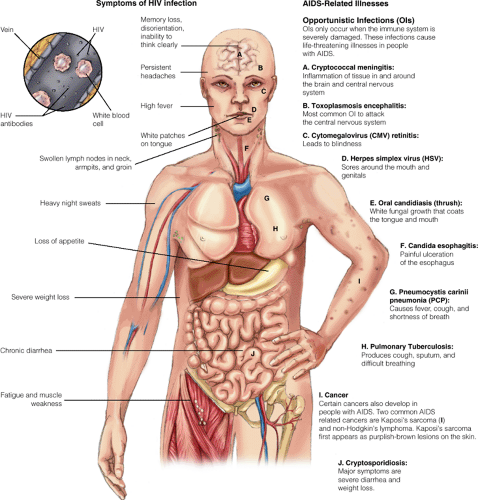

The AIDS virus attacks an individual’s immune system and emerges in the form of one or more of 12 secondary infectious diseases or opportunistic infectious diseases (an infection that occurs as a result of the individual’s weak or compromised immune system resulting from AIDS, cancer, or immunosuppressive drugs such as chemotherapy). Although the average time of the development of AIDS is about 10 years, HIV can occur between 6 months and 5 years after exposure to the virus. However, some people may carry the virus without showing symptoms of the disease for an indefinite period.

Secondary or Opportunistic Infectious Diseases

The two most common secondary or opportunistic infectious diseases found in AIDS clients are Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare form of skin cancer. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia is characterized by a chronic, nonproductive cough and dyspnea that may be severe enough to result in hypoxemia and cognitive impairment. Kaposi’s sarcoma presents with a blue-purple–tinted skin lesion.

Other most common infections are Toxoplasma gondii, caused by protozoa; Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans, caused by fungi; Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare, caused by bacteria; and viruses such as the herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus.

All of these infectious diseases associated with AIDS have extremely painful, debilitating, and devastating physical and psychosocial effects (Figure 34-2). The physical symptoms may include:

Nausea and vomiting

Constant fever

Chronic headaches

Diarrhea

Painful mouth infections

Hypotension

Liver and kidney failure

Severe respiratory distress

Incontinence

Central nervous system dysfunction with psychomotor retardation

Early Symptomatic HIV Infection

Early symptomatic HIV infection (also known as AIDS-related complex [ARC]) is the stage of viral infection caused by HIV in which symptoms have begun to manifest, but before the development of AIDS (North Arundel Hospital, 2003). It is characterized by chronically swollen lymph nodes and persistent fever, cough, weight loss, debilitating fatigue, diarrhea, night sweats,

and pain. One third to one half of these individuals will go on to develop AIDS, whereas the others will show no progression of the disease. Additional information pertaining to the medical aspect of AIDS and its impact on health care providers can be obtained in medical–surgical nursing textbooks. Extensive data is also available online (see Internet Resources on the Student Resource CD-ROM).

and pain. One third to one half of these individuals will go on to develop AIDS, whereas the others will show no progression of the disease. Additional information pertaining to the medical aspect of AIDS and its impact on health care providers can be obtained in medical–surgical nursing textbooks. Extensive data is also available online (see Internet Resources on the Student Resource CD-ROM).

HIV Infection and Neuropsychiatric Syndromes

Clients infected with the AIDS virus may develop an extensive array of neuropsychiatric syndromes (neurologic symptoms occurring as the result of organic disturbances of the central nervous system that constitute a recognizable psychiatric condition) such as HIV-associated dementia and HIV encephalopathy (Shahrokh & Hales, 2003). HIV-associated dementia is found in a large portion of clients infected with HIV; however, other causes of dementia (eg, vascular dementia or dementia secondary to substance abuse) also must be considered. HIV encephalopathy, a less severe form of neurologic dysfunction, is characterized by impaired cognitive functioning and reduced mental activity that interferes with activities of daily living, work, and social functioning. Delirium in HIV-infected clients is underdiagnosed. The etiology of dementia in HIV-infected clients can also cause clinical symptoms of delirium (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). (See Chapter 27 for additional information about clinical symptoms of dementia, delirium, and other cognitive disorders.) Box 34-1 lists the neurologic manifestations associated with HIV/AIDS.

Box 34.1: Neurologic Manifestations Associated With HIV/AIDS

Cognitive impairment (eg, ARC or dementia)

Delirium secondary to opportunistic infections, neoplasms, cerebrovascular changes, metabolic abnormalities, or medication used in the management of HIV/AIDS

Personality change

Mood disorder secondary to organic changes

Defusional disorder secondary to organic changes

Psychosis secondary to AIDS–dementia complex

Drug–drug interactions between psychotropics and antiretrovirals

Extrapyramidal symptoms secondary to the use of antipsychotic agents

Myelopathy

Demyelinating neuropathies

Psychosocial Impact of AIDS

AIDS is frequently described as a tragic and complex phenomenon that provokes a shattering emotional and psychosocial impact on all who are involved with the illness. Indeed, AIDS connects medicine and psychiatry to a greater degree than any other major illness. Certain population groups have been identified as at risk for the psychosocial impact of AIDS, including:

Clients in various stages of the illness

Sexual partners and family of individuals with AIDS

Individuals at particular risk for contracting the disease based on epidemiologic data

Individuals with a mental disorder (eg, substance abuse) who fear exposure but refuse to be tested

The most serious psychosocial problems occur for those clients who actually have the disease. Most people with AIDS are relatively young, were previously healthy, and had not experienced a major medical illness. The confirmation of this diagnosis can be catastrophic for the client, eliciting a series of emotional and social reactions. These reactions include:

A loss of self-esteem

Fear of the loss of physical attractiveness and rapid changes in body image

Feelings of isolation and stigmatization

An overwhelming sense of hopelessness and helplessness

A loss of control over their lives

In addition, emotional crises may result from the client’s increasing isolation as he or she attempts to cope with the nearly universal stigma faced on a daily basis. AIDS clients experience rejection from all parts of society, including significant others, families, friends, social agencies, landlords, and health care workers. For many, this constant rejection causes a re-living of the “coming-out process,” with a heightening of the associated anxiety, guilt, and internalized self-hatred. The fear of spreading AIDS to others can lead to further isolation and abandonment, commonly at a time when there is an ever-greater need for physical and emotional support. Clients with AIDS may respond with intense anger and hostility as their conditions deteriorate and they confront the everyday realities of this illness: loss of job and home, forced changes in lifestyle, the perceived lack of response by the medical community, and the often crippling expense associated with the illness.

HIV Infection and Psychiatric Disorders

Several comorbid psychiatric disorders have been observed in clients with HIV infection or AIDS. They include, but are not limited to, substance abuse, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, adjustment disorders, and psychotic disorders.

The frequency of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts may increase in clients who are informed of the presence of HIV infection or AIDS, especially if they have inadequate social or financial support, experience relapses, or face difficult social issues relating to their sexual identity or sexual preferences (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Box 34-2 describes the behavioral manifestations associated with HIV infection and AIDS. (See specific chapters for information regarding symptoms of and nursing interventions for substance abuse, anxiety, depression, adjustment reaction, and psychosis.)

The Worried Well

Individuals in high-risk groups who, although they test negative for the AIDS virus, have anxiety about contracting the virus are referred to as the worried well. Clinical symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, or hypochondriasis may develop if they do not receive reassurance that they are free of the AIDS virus (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). (See specific chapters for information regarding symptoms of and nursing interventions for anxiety and anxiety-related disorders).

Box 34.2: Behavioral Manifestations Associated With HIV/AIDS

Confrontation (eg, anger, aggressiveness, hostility, or impulsivity)

Impaired social functioning

Impaired occupational functioning

Overwhelming stress and anxiety due to preoccupation with clinical phenomena of HIV/AIDS

Sleep disturbances unrelated to stress, mood, or psychosocial problems but rather due to neuroendocrine dysfunctions, systemic inflammation, or obstructive sleep apnea

Lack of sexual function or interest due to fear of transmission of HIV, rejection by a partner, or hypogonadism

Suicide due to partial remission with an uncertain survival time after preparing oneself to die

Grief Reaction to HIV/AIDS

A four-stage grief reaction by clients diagnosed with AIDS has been described (Nichols, 1983). The reaction is similar to the pattern designated by Kübler-Ross in dying patients (Kübler-Ross, 1969; Nichols, 1983).

First Stage

The initial stage consists of shock, numbness, and disbelief. The severity of the reaction may depend on existing support systems for the individual. During this period, clients report sleep problems and an experience of depersonalization and derealization. For some, the acknowledgment of the AIDS diagnosis causes severe emotional paralysis or regression.

Second Stage

The second stage is denial, in which the person may attempt to ignore the diagnosis of AIDS. Although it may serve a necessary psychic function, this denial can cause the client to engage in behaviors that are both self-destructive and potentially dangerous to others. Some clients begin to plunge into complete isolation, avoiding human contact as much as possible.

Third Stage

In the third stage, the individual begins to question why he or she contracted AIDS. Expressions of guilt and anger are frequent as the client seeks to understand the reason for his or her illness. Homosexual or bisexual men may experience feelings of homophobia (ie, the unreasonable fear or hatred of homosexuals or homosexuality) and believe that God is punishing them for their homosexual preference.

Fourth or Final Stage

The fourth or final stage, that of resolution and acceptance, depends on the individual’s personality and ego integration. This stage may be signified by the acceptance of the illness and its limitations, a sense of peace

and dignity, and a preparation for dying. As the debilitating symptoms progress, however, other clients may become increasingly despondent and depressed, stop eating, express suicidal ideation, and develop almost-psychotic fixations and obsessions with their illness. A significant and growing number of AIDS clients make successful suicide attempts.

and dignity, and a preparation for dying. As the debilitating symptoms progress, however, other clients may become increasingly despondent and depressed, stop eating, express suicidal ideation, and develop almost-psychotic fixations and obsessions with their illness. A significant and growing number of AIDS clients make successful suicide attempts.

Effects of AIDS on Family Dynamics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree