Somatoform and Dissociative Disorders

These disorders encompass mind–body interactions in which the brain, in ways still not well understood, sends various signals that impinge on the patient’s awareness, indicating a serious problem in the body.

If worrying were harmless, it would not be much of a problem. But worrying does take its toll. And if you stress your system with excessive worry, it is likely to wear out earlier.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Discuss the following factors or theories related to somatoform disorders: biologic or genetic factors, organ specificity theory, Selye’s general adaptation syndrome, familial or psychosocial theory, and learning theory.

Explain the following theories related to dissociative disorders: state-dependent learning theory and psychoanalytic theory.

Compare and contrast the clinical symptoms of somatization and conversion disorders.

Distinguish between dissociative amnesia and dissociative fugue.

Differentiate between anxiety disorder due to a general medical condition and psychological factors affecting a medical condition.

Relate the importance of addressing medical issues and cultural differences when assessing a client with a somatoform or dissociative disorder.

Articulate at least five common nursing diagnoses appropriate for clients exhibiting somatoform or dissociative disorders.

Develop a list of interventions to reduce stress.

Key Terms

Depersonalization disorder

Dissociative amnesia

Dissociative disorder

Dissociative fugue

Dissociative identity disorder

Dysmorphobia

General adaptation syndrome (GAS)

La belle indifference

Primary gain

Pseudoneurologic manifestation

Secondary gain

Somatoform disorders

Anxiety can occur under many guises that are not readily recognized by the nurse or practicing clinician. For example, clients may experience anxiety as the result of a specific medical condition (eg, hyperparathyroidism), as a result of treatment for a specific medical condition (eg, thyroid medication), or as a result of changes in employment or lifestyle due to a medical condition (eg, myocardial infarct). Anxiety can also precipitate somatic complaints without a physical basis (eg, back pain or gastrointestinal [GI] symptoms) or interfere with the ability to recall important personal information, usually of a traumatic or stressful nature, that is too extensive to be explained by normal forgetfulness. Moreover, the emotional dimensions of medical conditions are often overlooked when medical care is given.

Chapter 19 described the more commonly seen anxiety disorders. This chapter provides an overview of the relationship between anxiety and real or perceived medical conditions and dissociative reactions such as amnesia, fugue, identity disorder, and depersonalization. Possible etiologic theories are discussed, and an overview of each disorder is presented. The steps of the nursing process focus on the more prominent clinical symptoms for each disorder.

Etiology of Somatoform and Dissociative Disorders

Several theories and research studies have attempted to explain the role of stress or emotions in the development or exacerbation of somatoform and dissociative disorders. Following is a brief discussion of these theories.

Theories Regarding Somatoform Disorders

Somatoform disorder is the diagnosis given to individuals who present with symptoms suggesting a physical disorder without demonstrable organic findings to explain the symptoms (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000). Theories regarding the etiology of somatoform disorders include biologic and genetic factors, the organ specificity theory, Selye’s general adaptation syndrome, the familial or psychosocial theory, and the learning theory.

Biologic and Genetic Factors

Research has suggested that biologic and genetic factors are responsible for the development of certain somatoform disorders. A limited number of brain-imaging studies of clients with clinical symptoms of somatoform disorders have reported decreased metabolism in the frontal lobes and in the nondominant hemisphere (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Some studies point to a neuropsychological basis for the development of somatization disorder. These studies propose that clients have attention and cognitive impairments that result in faulty perception and assessment of somatosensory inputs.

Genetic data indicate that somatization disorder tends to run in families, occurring in 10% to 20% of the first-degree female relatives of clients with somatization disorder. Research into cytokines (messenger molecules of the immune system that communicate with the nervous system, including the brain) indicates that abnormal regulation of the cytokine system may contribute to the development of nonspecific symptoms of somatoform disorders (eg, hypersomnia, anorexia, fatigue, and depression) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Organ Specificity Theory

In 1953, Lacey, Bateman, and Van Lehn studied characteristic physiologic response patterns that they believed to be present since childhood. They concluded that a person responds to stress primarily with physical manifestations in one specific organ or system, thereby showing susceptibility to the development of a specific disease. This theory is referred to as the organ specificity theory. For example, when faced with an emotional conflict, a 25-year-old woman experiences the sudden onset of lower abdominal pain and diarrhea (conversion disorder). The pain and diarrhea give the client a legitimate reason to avoid conflict and persist until the conflict is resolved. She has the potential for development of irritable bowel syndrome if she continues to experience frequent episodes of stress. Other persons may be prone to low back pain, asthmatic attacks, or skin rashes, depending on their susceptible organ or system.

Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome

According to Hans Selye (1978), an individual who copes with the demands of stress experiences a “fight-or-flight”

reaction. The body puts into effect a set of responses that seeks to diminish the impact of a stressor and restore homeostasis. This reaction, termed general adaptation syndrome (GAS), occurs in three stages: alarm reaction; resistance in which adaptation is ideally achieved; and exhaustion, in which acquired adaptation or resistance to the stressor is lost. If adaptation occurs, stress does not have a negative effect on an individual’s emotional or physical well-being (ie, the “fight” has been won). However, emotional disorders such as anxiety, physical deterioration secondary to a somatoform disorder, or death can occur as a result of continued stress in the presence of a weakened physical condition (ie, the “fight” is lost because the body could not restore homeostasis) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

reaction. The body puts into effect a set of responses that seeks to diminish the impact of a stressor and restore homeostasis. This reaction, termed general adaptation syndrome (GAS), occurs in three stages: alarm reaction; resistance in which adaptation is ideally achieved; and exhaustion, in which acquired adaptation or resistance to the stressor is lost. If adaptation occurs, stress does not have a negative effect on an individual’s emotional or physical well-being (ie, the “fight” has been won). However, emotional disorders such as anxiety, physical deterioration secondary to a somatoform disorder, or death can occur as a result of continued stress in the presence of a weakened physical condition (ie, the “fight” is lost because the body could not restore homeostasis) (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Familial or Psychosocial Theory

Proponents of the familial or psychosocial theory assert that characteristics of dynamic family relationships, such as parental teaching, parental example, and ethnic mores, may influence the development of a somatoform disorder. According to family therapist Salvador Minuchin (1974), role modeling is an important factor in personality development. He identified the “psychomatogenic family” as a group of individuals who internalize feelings of anxiety or frustration rather than express their feelings in a direct manner. As a result of this internalization, they develop physiologic symptoms rather than face or resolve conflict. Children of such families observe the coping mechanisms of their parents and other family members, developing similar behaviors when the need arises, thereby avoiding conflict and experiencing positive reinforcement.

Learning Theory

According to the learning theory, a person learns to produce a physiologic response (somatization) to achieve a reward, attention, or some other reinforcement. Jeanette Lancaster (1980) states that the following dynamics occur during the development of this learned response:

The learning is of an unconscious nature.

There was a reward or reinforcement in the past when the person experienced specific physiologic symptoms.

Reinforcement can be positive or negative. Negative reinforcement is considered better than no reinforcement at all.

The person is unable to give up the disorder willfully.

For example, a child stays home from school when he is ill and receives attention from his mother as she reads to him, fixes his favorite meals, and monitors his vital signs. As a result of this experience, he unconsciously learns to produce physiologic symptoms of a migraine headache or an upset stomach as he feels the need for attention. This behavior may continue throughout his life as he attempts to satisfy unmet needs.

Theories Regarding Dissociative Disorders

The diagnosis of dissociative disorder is given to individuals who exhibit the separation of an idea or mental thoughts from conscious awareness or from emotional significance and affect (APA, 2000). Some examples of dissociative disorders are dissociative amnesia (the inability to recall important personal details because of a psychological or physical trauma), dissociative fugue (a person’s sudden and unexpected departure from home or work and inability to recall the past), dissociative identity disorder (also known as multiple personality disorder), and depersonalization disorder (patient experiences a distorted perception of self, body, and life, associated with a feeling of unreality). Theories regarding the etiology of dissociative disorders include the state-dependent learning theory and psychoanalytic theory. Various causative factors have also been identified. Specific disorders will be discussed at length later in the chapter; below are some brief examples to illustrate each theory.

State-Dependent Learning Theory

The theory of state-dependent learning states that dissociative amnesia is caused by stress associated with traumatic experiences endured or witnessed (eg, abuse, rape, combat, natural disasters); major life stresses (eg, abandonment, death of a loved one, financial troubles); or tremendous internal conflict (eg, turmoil over guilt-ridden impulses, apparently unresolvable interpersonal difficulties, criminal behaviors). Memory of the event is laid down during the event, and the emotional state may be so extraordinary that it is hard for an affected person to remember information learned during the event. Furthermore, some individuals are believed to be more predisposed to the

development of dissociative amnesia (eg, those who are easily hypnotized) (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

development of dissociative amnesia (eg, those who are easily hypnotized) (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Theorists believe the cause of dissociative fugue is similar to that of dissociative amnesia, with some additional factors. Fugue is thought to remove an individual from accountability for one’s actions and may absolve one of certain responsibilities, remove one from an embarrassing situation or intolerable stress, reduce one’s exposure to a perceived hazard such as a dangerous, risk-taking job, or protect one from suicidal or homicidal impulses (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 2005).

Psychoanalytic Theory

According to psychoanalytic theory, dissociative amnesia is considered to be a defense mechanism whereby an individual alters consciousness as a way of dealing with an emotional conflict or an external stressor. Secondary defenses include repression, which blocks disturbing impulses from consciousness and denial which allows the conscious mind to ignore external reality (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Other Factors

The cause of dissociative identity disorder is unknown; however, four types of causative factors have been identified: a traumatic life event (usually childhood physical or sexual abuse), vulnerability for the disorder to develop, environmental factors, and the absence of external support. Death of a close relative or friend during childhood or witnessing a trauma or death are also traumatic events that can precipitate the development of dissociative identity disorder.

Depersonalization disorder frequently occurs in life-threatening danger such as accidents, assaults, and serious illnesses and injuries. Although it has not been studied widely, depersonalization disorder may be caused by psychological, neurologic, or systemic disease. It has been associated with epilepsy, brain tumors, sensory deprivation, and emotional trauma as well as with an array of abused substances (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, 2005; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics

The more common physiologic, psychological or emotional, behavioral, and intellectual or cognitive symptoms of anxiety were discussed in Chapter 19. The features, clinical symptoms, and diagnostic characteristics specific to somatoform and dissociative disorders, as well as the relationship between anxiety and medical conditions, based on the information described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), are presented in this chapter (APA, 2000).

Somatoform Disorders

According to the DSM-IV-TR, somatoform disorders are reflected in disordered physiologic complaints or symptoms, are not under voluntary control, and do not demonstrate organic findings. Although symptoms in all of the somatoform disorders cause impairment in social or occupational functioning or create significant emotional distress, the complaints are not fully explained by the objective physical findings (Adams, 2003).

Somatoform disorders are often encountered in general medical settings. There are seven types of somatoform disorders:

Body dysmorphic disorder

Somatization disorder

Conversion disorder

Pain disorder

Hypochondriasis

Undifferentiated somatoform disorder

Somatoform disorder, not otherwise specified

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

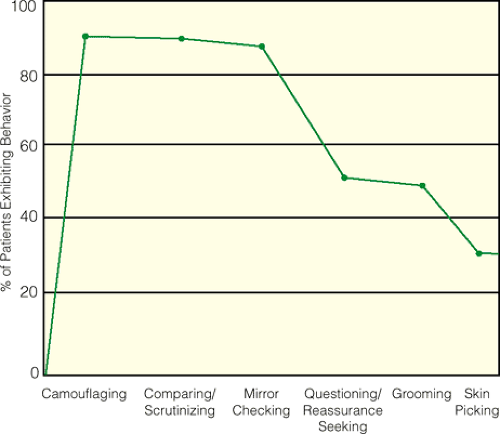

Individuals with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) have a pervasive subjective feeling of ugliness and are preoccupied with an imagined defect in physical appearance or a vastly exaggerated concern about a minimal defect. The person believes or fears that he or she is unattractive or even repulsive. The fear is rarely assuaged by reassurance or compliments. If a slight physical abnormality exists (eg, hair, skin, or facial flaws), the person displays excessive concern about it. This preoccupation causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. Obsessive–compulsive traits (Figure 20-1) and a depressive syndrome are frequently present. The most common age of onset of BDD is from adolescence through the third decade of life. Prognosis is unknown because this disorder can persist for several years (Phillips, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Previous research suggests this group has poor mental health–related quality of life and high

lifetime rates of psychiatric hospitalization, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Phillips, Siniscalchli, & McElroy, 2004).

lifetime rates of psychiatric hospitalization, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts (Phillips, Siniscalchli, & McElroy, 2004).

Figure 20.1 Ritualistic behaviors, including obsessive–compulsive traits, in body dysmorphic disorder. |

The prevalence of BDD (historically known as dysmorphobia) in the community is unknown. However, reported rates in clinical mental health settings range from under 5% to approximately 40%. Reported rates in cosmetic surgery and dermatology settings range from 6% to 15% (APA, 2000). According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), the top five cosmetic surgery procedures in 2003 included nose reshaping, liposuction, breast augmentation, eyelid surgery, and face-lift (ASPS, 2004). Cultural concerns about physical appearance and the importance of proper physical appearance may influence preoccupation with an imagined physical deformity (Figure 20-2). BDD may be equally common in women and men of various cultures. Average age of onset is 16, although diagnosis often doesn’t occur for another 10 to 15 years (APA, 2000).

Somatization Disorder

Somatization (Briquet’s) disorder was originally described by Briquet in 1859. It is a chronic, severe anxiety disorder in which a client expresses emotional turmoil or conflict through significant physical complaints (including pain and GI, sexual, and neurologic symptoms), usually with a loss or alteration of physical functioning. Such a loss or alteration is not under voluntary control and is not explained as a known physical disorder. Somatization disorder differs from other somatoform disorders because of the multiple complaints voiced and the multiple organ systems affected.

This disorder is often familial. Although etiology is unknown, it is believed that marked dependency and intolerance of frustration contribute to the verbalization of physical complaints representing an unconscious plea for attention and care. The prevalence of this disorder varies from 5% to 10% in primary care populations, with a female predominance ratio of 20 to 1 (APA, 2000). The onset usually occurs before age 25 years. It is considered a chronic illness in persons demonstrating a dramatic, confusing, or complicated medical history, because they seek repeated medical attention. The physical symptoms or complaints that occur in the absence of any medical explanation govern the person’s life, influencing the person to take medication, alter lifestyle, or see a physician. The symptoms are not intentionally produced or feigned. When there is a related general medical condition, the physical complaints or resulting social or occupational impairment are in excess of what would be

expected from history, physical examination, or laboratory findings.

expected from history, physical examination, or laboratory findings.

In addition, anxiety and depression often are seen, and the client may make frequent suicide threats or attempts. The person also may exhibit antisocial behavior or experience occupational, interpersonal, or marital difficulties. Because the client constantly seeks medical attention, he or she frequently submits to unnecessary surgery (APA, 2000; Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

The type and frequency of somatic symptoms differ across cultures. For example, there is a higher reported frequency of somatization disorder in Greek and Puerto Rican men than in men in the United States. Therefore, the symptom reviews must be adjusted to the culture.

Conversion Disorder

Conversion disorder is a somatoform disorder that involves motor or sensory problems suggesting a neurologic condition. It has been described as an adaptation to a frustrating life experience in which the client utilizes pantomime when direct verbal communication is blocked (Ford & Folks, 1985; Maldonado, 1999). Anxiety-provoking impulses are converted unconsciously into functional symptoms.

The phrase la belle indifference is used to describe client reactions such as showing inappropriate lack of concern about the symptoms and displaying no anxiety. This is because the anxiety has been relieved by the conversion disorder. Clients may also exhibit a pseudoneurologic manifestation (sensory or motor loss that does not follow neurologic function but rather comes and goes with stress or a functional need). For example, when suddenly awakened or startled, the sensory or motor loss is briefly gone.

Four subtypes of conversion disorder have been identified, based on the nature of presenting symptoms or deficit. These subtypes are highlighted in Box 20-1.

Although the disturbance is not under voluntary control, the symptoms occur in organs that are voluntarily controlled. Conversion symptoms serve four functions:

Permit the client to express a forbidden wish or impulse in a masked form

Impose punishment via the disabling symptom for a forbidden wish or wrong-doing

Remove the client from an overwhelming life-threatening situation (primary gain)

Allow gratification of dependency (secondary gain) (Maldonado, 1999).

Box 20.1: Subtypes of Conversion Disorders

Motor symptoms or deficit such as impaired balance, paralysis of an upper or lower extremity, dysphagia, or urinary retention

Sensory symptoms or deficit such as anesthesia or loss of touch or pain sensation, double vision, blindness, or hallucinations

Seizures or convulsions with voluntary motor or sensory components

Mixed presentation if symptoms are of more than one category

Primary gain allows relief from anxiety by keeping an internal need or conflict out of awareness. Secondary gain refers to any other benefit or support from the environment that a person obtains as a result of being sick. Examples of secondary gain are attention, love, financial reward, and sympathy.

Malingering and factitious disorder must be differentiated from conversion disorder, which occurs as a result of unconscious motivation. Malingering is the production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms that are consciously motivated by external incentives to avoid an unpleasant situation (eg, to avoid work or to obtain drugs). Malingering may also represent adaptive behavior to avoid a traumatic situation (eg, feigning illness to avoid incarceration). Factitious disorder is the consciously motivated production or feigning of physical or psychological symptoms to assume the sick role. External incentives such as economic gain or avoidance of legal responsibility are absent (APA, 2000; Maldonado, 1999).

Several studies have reported that 5% to 15% of psychiatric consultations in the general hospital population and 25% to 40% of Veterans Administration hospital consultations involve clients with conversion disorder. Conversion disorder occurs in 1% to 3% of clients referred to mental health clinics. The onset can occur at any time; however, it is more common in adolescents and young adults. Comorbid psychiatric disorders include major depressive disorder, other anxiety disorders, and schizophrenia (Sadock & Sadock, 2003). Conversion disorder occurs more frequently in the rural population, in individuals of lower

socioeconomic status, and in individuals less knowledgeable about medical and psychological concepts. Higher rates are also reported in developing regions (APA, 2000).

socioeconomic status, and in individuals less knowledgeable about medical and psychological concepts. Higher rates are also reported in developing regions (APA, 2000).

Although the disorder may occur for the first time during middle age or later maturity, the typical age of onset is usually late childhood or early adulthood. Such a disorder frequently impairs normal activities, possibly leading to the development of a chronic sick role. Studies suggest that a considerable number of clients diagnosed with conversion disorder may develop a disease process at some time in the future, which may explain the pathological findings presented initially (Maldonado, 1999). See Clinical Example 20-1: The Client Exhibiting Conversion Disorder.

Clinical Example 20.1: The Client Exhibiting Conversion Disorder

BJ, a 45-year-old female, lived on a farm with her husband and three childen ages 17, 15, and 12 years. The 17-year-old son assisted his father with several chores, including driving the farm equipment while harvesting crops.

One afternoon, BJ’s husband and son did not return for dinner. BJ was quite concerned and asked her daughters to go to the field where her husband was harvesting wheat to see why they were late. Approximately 20 minutes later, both daughters returned and informed their mother that their brother had been injured in an accident and was taken to the hospital by neighbors. They were told that their brother had “mangled” his right arm in the farm equipment.

As BJ listened to her daughters, she became quite upset. When her husband returned from the hospital, BJ complained of localized weakness and double vision, and exhibited an unsteady gait. Her husband insisted that she be seen in the emergency room prior to visiting with her son. BJ was given a thorough physical examination, which ruled out any physiologic cause. The emergency room physician spoke to BJ about her son’s accident and determined that BJ was exhibiting clinical symptoms of conversion disorder secondary to anxiety related to her son’s traumatic injury.

Pain Disorder

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage” (Victoroff, 2001, p. 20). The diagnosis of pain disorder is given when an individual experiences significant pain without a physical basis for pain or with pain that greatly exceeds what is expected based on the extent of injury. In order for there to be a diagnosis of pain disorder, the pain must disrupt social and/or occupational functioning. For example, an individual who has a history of a back injury verbalizes an increase in pain during the course of financial difficulties and informs his employer that he is unable to work. External factors may amplify the client’s clinical symptoms (Adams, 2003).

Although pain disorder may occur at any stage of life, it occurs more frequently in the fourth or fifth decade of life; is more frequent in women who complain of chronic pain such as headaches and musculoskeletal pain; is more common in persons with blue-collar occupations; and occurs in approximately 40% of those individuals who complain of pain. Approximately 10% to 15% of adults in the United States have some form of work disability due to back pain. Comorbid psychiatric disorders include depression, anxiety, and substance abuse (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access