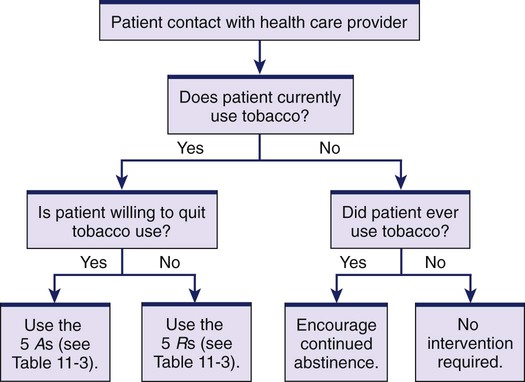

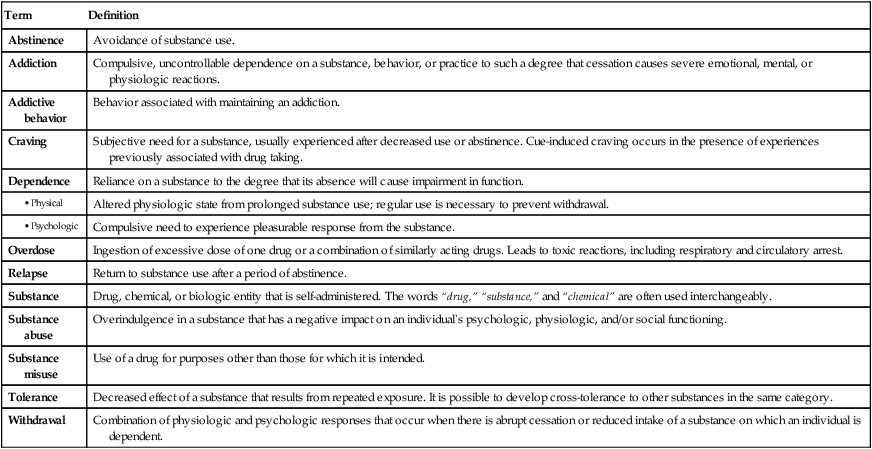

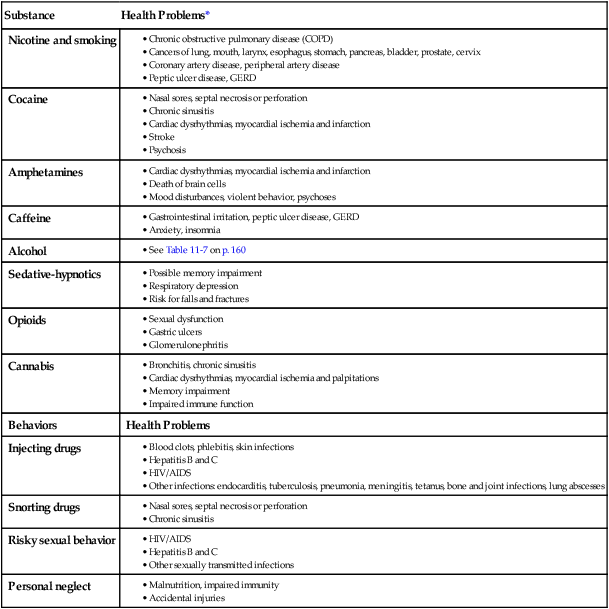

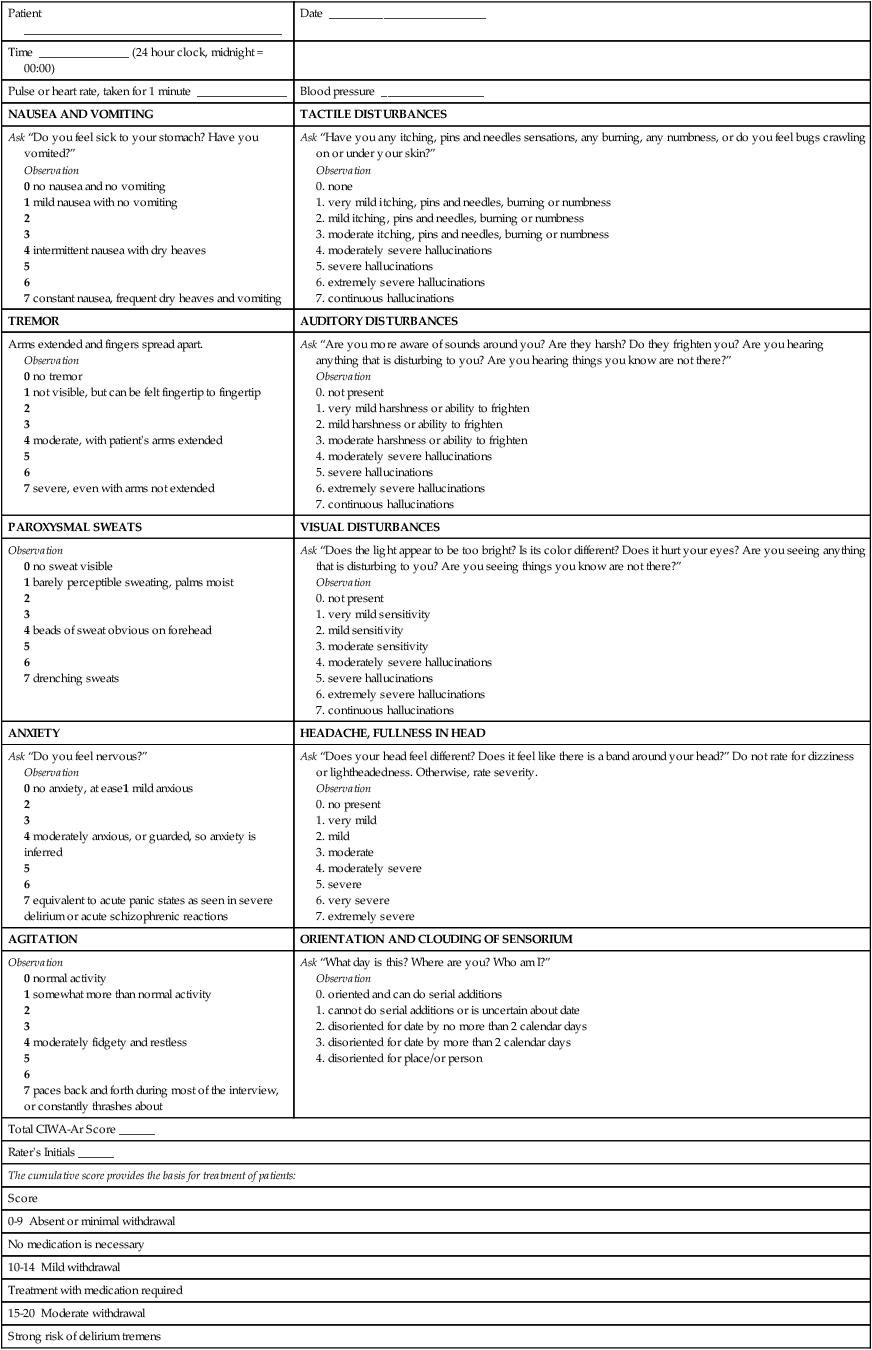

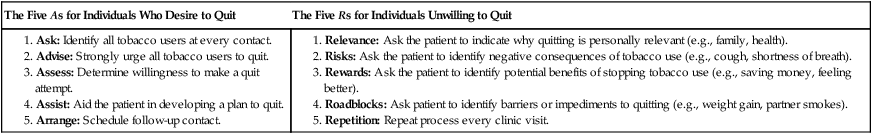

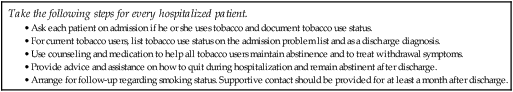

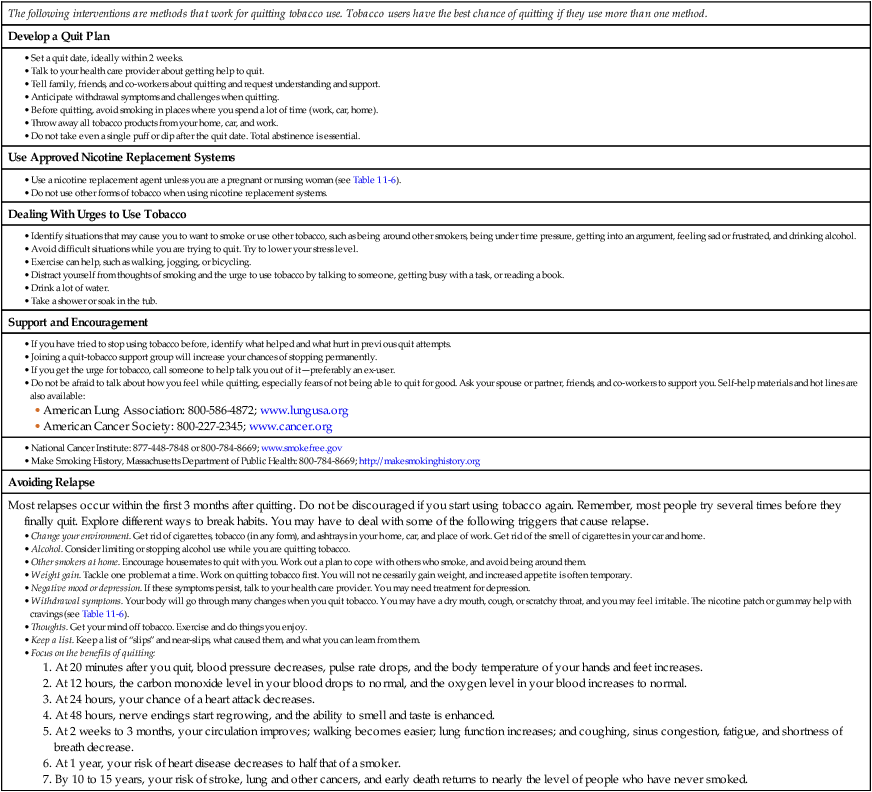

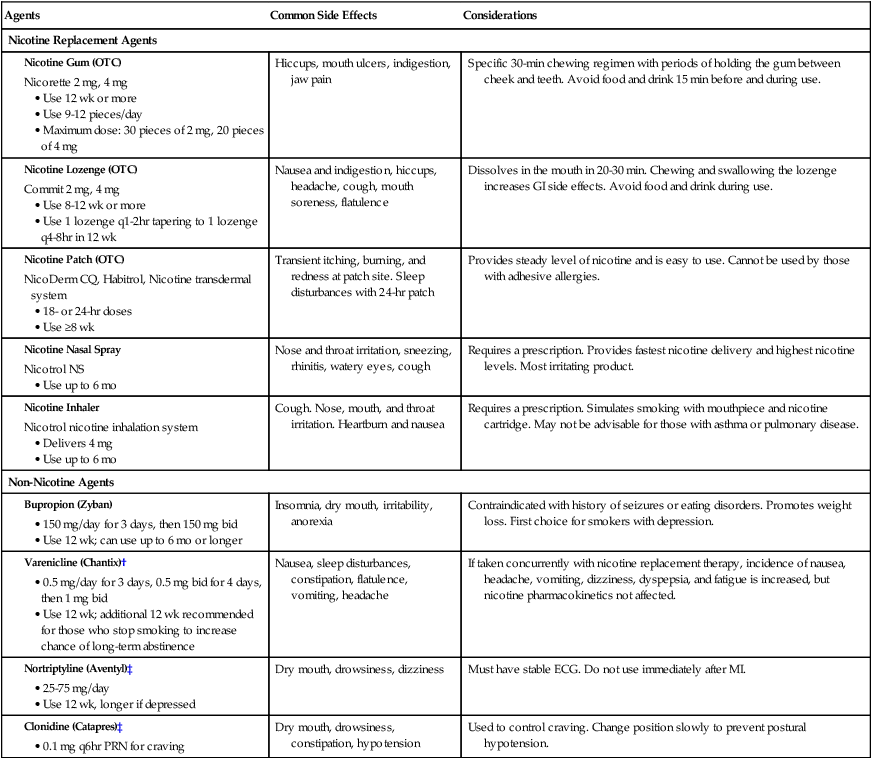

If you are on the wrong road, progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road. 1. Apply the terms addiction, addictive behavior, substance misuse, substance abuse, dependence, tolerance, withdrawal, craving, and abstinence to clinical situations. 2. Relate the effects of substance abuse to its resulting major health complications. 3. Differentiate among the effects of the use of stimulants, depressants, and cannabis. 4. Explain your role in promoting the cessation of smoking and tobacco use. 5. Summarize the nursing management and collaborative care of patients who experience intoxication, overdose, or withdrawal from stimulants and depressants. 6. Describe the incidence and effects of substance abuse and dependence in the older adult. Substance abuse and addiction are serious problems affecting the health care system and society today. Addiction to chemical substances usually includes dependence on psychoactive agents that result in pleasure or modify thinking and perception. These include substances that are legal for adult use such as alcohol and tobacco, and illicit drugs including marijuana/hashish, cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens, inhalants, and prescription medications used nonmedically. In 2010 an estimated 22.6 million Americans ages 12 or older, or 8.9% of the population, were using illicit drugs monthly.1 Americans’ abuse and misuse of prescription medications such as analgesics, sedative-hypnotics, tranquilizers, and amphetamines have increased and can create harmful effects that are more deadly than the abuse of illicit drugs.2 The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV states that substance abuse and dependence (defined in Table 11-1) are specific psychiatric diagnoses.3 Abused substances are discussed in detail in psychiatric and pharmacologic books and resources. Long-term management of patients who abuse substances is most often provided in specialized treatment facilities that provide both drug and behavior therapies. TABLE 11-1 TERMINOLOGY OF SUBSTANCE ABUSE Individuals who abuse substances use the health care system more than those who do not.4 Almost every drug of abuse harms some tissue or organ in addition to the brain. Some health problems are caused by the effects of specific drugs, such as liver damage related to alcohol use or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) related to smoking. Other health problems result from behaviors associated with substance abuse, such as injecting drugs or neglecting nutrition and hygiene. Common health complications related to substance abuse are identified in Table 11-2. TABLE 11-2 COMMON HEALTH PROBLEMS RELATED TO SUBSTANCE ABUSE • See Table 11-7 on p. 160 GERD, Gastroesophageal reflux disease. *The health problems related to substance abuse are discussed in the appropriate chapters throughout the text where they are identified as risk factors for these problems. Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse: Addiction and health. In NIDA: Drugs, brains, and behavior—the science of addiction, NIH pub no 07-5605, Rockwell, Md, 2008, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from www.nida.nih.gov/scienceofaddiction/health.html. eTABLE 11-1 CLINICAL INSTITUTE WITHDRAWAL ASSESSMENT OF ALCOHOL SCALE, REVISED (CIWA-Ar) The CIWA-Ar is not copyrighted and may be reproduced freely. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al: Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: The revised Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict 84:1353, 1989. The addictive behavior that you are most likely to encounter is tobacco use. Nicotine is a stimulant substance in tobacco and is the most rapidly addictive of commonly abused drugs. Cigarette smoking is the predominant form of tobacco abuse in the United States. Tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable illness and death in the United States, claiming 443,000 lives a year.5 Smoking is the most harmful method of nicotine use and can injure nearly every organ in the body. Smoking causes chronic lung disease, cardiovascular disease, and many cancers, and it is associated with cataracts, pneumonia, periodontitis, and abdominal aortic aneurysm6 (see Table 11-2). The chronic respiratory irritation caused by exposure to cigarette smoke is a key risk factor in the development of COPD and lung cancer (carcinogens in tobacco are also involved). The toxic gases inhaled in cigarette smoke constrict the bronchi, paralyze the cilia, thicken the mucus-secreting membranes, dilate the distal airways, and destroy the alveolar walls. Women appear to be at greater risk than men for smoking-related diseases. Smoking in women is associated with increased menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea, early menopause, and infertility. Lung cancer related to smoking has surpassed breast cancer as the leading cause of cancer deaths among women.7 Although those who use smokeless tobacco (snuff, plug, and leaf) have less risk of lung disease than smokers, the use of smokeless tobacco is not without complications. Holding tobacco in the mouth increases the risk of cancer of the mouth, the cheek, the tongue, and gingiva nearly 50-fold. Smokeless tobacco users also experience the systemic effects of nicotine on the cardiovascular system, thus increasing the risk for cardiovascular disease.6 All users of nicotine in any form may develop complications directly related to the effects of nicotine itself, including an increased risk for peripheral artery disease, delayed wound healing, peptic ulcer disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).6 With each patient encounter, encourage the patient to quit and offer specific smoking cessation interventions. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has issued clinical practice guidelines for clinicians, including nurses, to use to motivate users to quit8 (Tables 11-3 and 11-4 and Fig. 11-1). Use these brief clinical interventions, called the “five As,” with each patient encounter. These interventions are designed to identify tobacco users, encourage them to quit, determine their willingness to quit, assist them in quitting, and arrange for follow-up to prevent relapse. TABLE 11-3 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: AHCPR supported clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update, Washington, DC, 2008, US Public Health Service. TABLE 11-4 INPATIENT TOBACCO CESSATION INTERVENTIONS Source: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: AHCPR supported clinical practice guideline: treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update, Washington, DC, 2008, US Public Health Service. If a tobacco user is unwilling to quit, motivational interventions based on the principles of motivational interviewing have been shown to increase future quit attempts. The content areas that should be addressed in a motivational counseling intervention can be captured by the “five Rs”: relevance, risks, rewards, roadblocks, and repetition. A patient teaching guide (Table 11-5) expands on the fourth “A” strategy, “Assist: aid the patient in quitting.” TABLE 11-5 PATIENT TEACHING GUIDE Sources: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Help for smokers and other tobacco users: consumer guide, Washington, DC, May 2008, US Public Health Service. Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov/consumer/tobacco/helpsmokers.htm; and American Lung Association: Freedom from smoking online. Retrieved from www.lungusa.org. The patient is most likely to achieve long-term tobacco cessation with a combination of nicotine replacement products, medications, behavioral approaches, and support.9 Support the patient by providing the resources needed to continue or start a quit attempt. A variety of nicotine replacement products can be used to reduce the craving and withdrawal symptoms associated with tobacco cessation (Table 11-6). These agents enable a smoker to reduce nicotine previously obtained from cigarettes with a system that delivers the drug more slowly and eliminates the carcinogens and gases associated with tobacco smoke. Nicotine replacement therapy is generally not recommended for pregnant women and people who have experienced an acute myocardial infarction within 2 weeks, have unstable angina, or have life-threatening dysrhythmias. TABLE 11-6 DRUG THERAPY *OTC nicotine replacement agents are also available in generic forms. Additional information and patient instructions are available from the American Lung Association at www.lungusa.org. †See the Drug Alert for varenicline on p. 157. ‡Nortriptyline and clonidine are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of smoking cessation but have been used successfully for this purpose. Non-nicotine drugs may also be used in smoking cessation. Bupropion (Zyban) is an antidepressant approved as an aid to quit smoking. It reduces the urge to smoke, reduces some symptoms of withdrawal, and helps prevent weight gain associated with smoking cessation. Nortriptyline (Aventyl) and clonidine (Catapres) are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in smoking cessation, but are used in some cases to reduce withdrawal symptoms and promote cessation.10

Substance Abuse

Term

Definition

Abstinence

Avoidance of substance use.

Addiction

Compulsive, uncontrollable dependence on a substance, behavior, or practice to such a degree that cessation causes severe emotional, mental, or physiologic reactions.

Addictive behavior

Behavior associated with maintaining an addiction.

Craving

Subjective need for a substance, usually experienced after decreased use or abstinence. Cue-induced craving occurs in the presence of experiences previously associated with drug taking.

Dependence

Reliance on a substance to the degree that its absence will cause impairment in function.

Altered physiologic state from prolonged substance use; regular use is necessary to prevent withdrawal.

Compulsive need to experience pleasurable response from the substance.

Overdose

Ingestion of excessive dose of one drug or a combination of similarly acting drugs. Leads to toxic reactions, including respiratory and circulatory arrest.

Relapse

Return to substance use after a period of abstinence.

Substance

Drug, chemical, or biologic entity that is self-administered. The words “drug,” “substance,” and “chemical” are often used interchangeably.

Substance abuse

Overindulgence in a substance that has a negative impact on an individual’s psychologic, physiologic, and/or social functioning.

Substance misuse

Use of a drug for purposes other than those for which it is intended.

Tolerance

Decreased effect of a substance that results from repeated exposure. It is possible to develop cross-tolerance to other substances in the same category.

Withdrawal

Combination of physiologic and psychologic responses that occur when there is abrupt cessation or reduced intake of a substance on which an individual is dependent.

Substance

Health Problems*

Nicotine and smoking

Cocaine

Amphetamines

Caffeine

Alcohol

Sedative-hypnotics

Opioids

Cannabis

Behaviors

Health Problems

Injecting drugs

Snorting drugs

Risky sexual behavior

Personal neglect

Patient ___________________________________________

Date __________________________

Time _______________ (24 hour clock, midnight = 00:00)

Pulse or heart rate, taken for 1 minute _______________

Blood pressure _________________

NAUSEA AND VOMITING

TACTILE DISTURBANCES

Ask “Do you feel sick to your stomach? Have you vomited?”

Observation

0 no nausea and no vomiting

1 mild nausea with no vomiting

2

3

4 intermittent nausea with dry heaves

5

6

7 constant nausea, frequent dry heaves and vomiting

Ask “Have you any itching, pins and needles sensations, any burning, any numbness, or do you feel bugs crawling on or under your skin?”

Observation

TREMOR

AUDITORY DISTURBANCES

Arms extended and fingers spread apart.

Observation

0 no tremor

1 not visible, but can be felt fingertip to fingertip

2

3

4 moderate, with patient’s arms extended

5

6

7 severe, even with arms not extended

Ask “Are you more aware of sounds around you? Are they harsh? Do they frighten you? Are you hearing anything that is disturbing to you? Are you hearing things you know are not there?”

Observation

PAROXYSMAL SWEATS

VISUAL DISTURBANCES

Observation

0 no sweat visible

1 barely perceptible sweating, palms moist

2

3

4 beads of sweat obvious on forehead

5

6

7 drenching sweats

Ask “Does the light appear to be too bright? Is its color different? Does it hurt your eyes? Are you seeing anything that is disturbing to you? Are you seeing things you know are not there?”

Observation

ANXIETY

HEADACHE, FULLNESS IN HEAD

Ask “Do you feel nervous?”

Observation

0 no anxiety, at ease1 mild anxious

2

3

4 moderately anxious, or guarded, so anxiety is inferred

5

6

7 equivalent to acute panic states as seen in severe delirium or acute schizophrenic reactions

Ask “Does your head feel different? Does it feel like there is a band around your head?” Do not rate for dizziness or lightheadedness. Otherwise, rate severity.

Observation

AGITATION

ORIENTATION AND CLOUDING OF SENSORIUM

Observation

0 normal activity

1 somewhat more than normal activity

2

3

4 moderately fidgety and restless

5

6

7 paces back and forth during most of the interview, or constantly thrashes about

Ask “What day is this? Where are you? Who am I?”

Observation

Total CIWA-Ar Score ______

Rater’s Initials ______

The cumulative score provides the basis for treatment of patients:

Score

0-9 Absent or minimal withdrawal

No medication is necessary

10-14 Mild withdrawal

Treatment with medication required

15-20 Moderate withdrawal

Strong risk of delirium tremens

>20 Severe withdrawal

Common Drugs of Abuse

Nicotine

Effects of Use and Complications

Nursing and Collaborative Care Tobacco Use

Tobacco Cessation

Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence

Smoking and Tobacco Use Cessation

Smoking Cessation*

Agents

Common Side Effects

Considerations

Nicotine Replacement Agents

Hiccups, mouth ulcers, indigestion, jaw pain

Specific 30-min chewing regimen with periods of holding the gum between cheek and teeth. Avoid food and drink 15 min before and during use.

Nausea and indigestion, hiccups, headache, cough, mouth soreness, flatulence

Dissolves in the mouth in 20-30 min. Chewing and swallowing the lozenge increases GI side effects. Avoid food and drink during use.

Transient itching, burning, and redness at patch site. Sleep disturbances with 24-hr patch

Provides steady level of nicotine and is easy to use. Cannot be used by those with adhesive allergies.

Nose and throat irritation, sneezing, rhinitis, watery eyes, cough

Requires a prescription. Provides fastest nicotine delivery and highest nicotine levels. Most irritating product.

Cough. Nose, mouth, and throat irritation. Heartburn and nausea

Requires a prescription. Simulates smoking with mouthpiece and nicotine cartridge. May not be advisable for those with asthma or pulmonary disease.

Non-Nicotine Agents

Insomnia, dry mouth, irritability, anorexia

Contraindicated with history of seizures or eating disorders. Promotes weight loss. First choice for smokers with depression.

Nausea, sleep disturbances, constipation, flatulence, vomiting, headache

If taken concurrently with nicotine replacement therapy, incidence of nausea, headache, vomiting, dizziness, dyspepsia, and fatigue is increased, but nicotine pharmacokinetics not affected.

Dry mouth, drowsiness, dizziness

Must have stable ECG. Do not use immediately after MI.

Dry mouth, drowsiness, constipation, hypotension

Used to control craving. Change position slowly to prevent postural hypotension.

Substance Abuse

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access