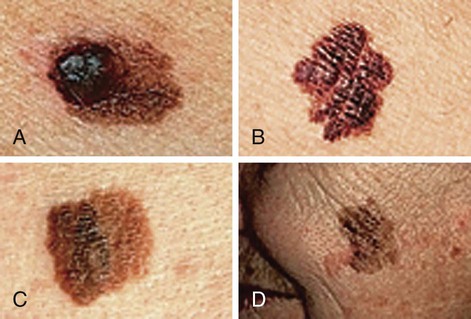

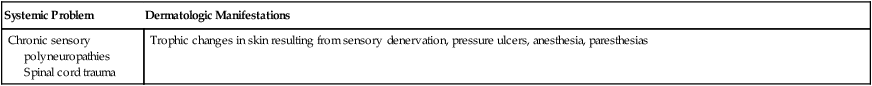

Chapter 24 1. Specify health promotion practices related to the integumentary system. 2. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of common acute dermatologic problems. 3. Summarize the psychologic and physiologic effects of chronic dermatologic conditions. 4. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of malignant dermatologic disorders. 5. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections of the integument. 6. Describe the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of infestations and insect bites. 7. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management of allergic dermatologic disorders. 8. Explain the etiology, clinical manifestations, and nursing and collaborative management related to benign dermatologic disorders. 9. Distinguish the dermatologic manifestations of common systemic diseases. 10. Explain the indications and nursing management related to common cosmetic procedures and skin grafts. eTABLE 24-1 DISEASES WITH DERMATOLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS* Safe sun practices are important for you to emphasize to the patient. Specific wavelengths of the sun (Table 24-1) have different effects on the skin. Sunlight is composed of visible light and UV light. There are two types of UV light: UVA and UVB. UVA light is responsible for tanning and UVB for sunburn. Both types can damage the skin and increase the risk of skin cancer. Both UVA and UVB can cause collagen damage and accelerate the aging of skin. Tanning is the skin’s response to injury and is caused by the increased production of melanin. When sun exposure is excessive, the turnover time of the skin becomes shortened, which can result in peeling. Fair-skinned persons should be especially cautious about excessive sun exposure because they have less melanin and thus less natural protection. TABLE 24-1 WAVELENGTHS OF SUN AND EFFECTS ON SKIN Other factors that increase the possibility of sunburn include being at high altitude, being in snow (reflects 80% of the sun’s rays), or being in or near water. Warn people of the dangers of tanning booths and sun lamps, which are UVA. Tanning booths increase the risk of sunburn and contribute to the development of skin cancer.1 The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rates sunscreen products on their sun protection factor (SPF). The SPF measures the effectiveness of a sunscreen in filtering and absorbing UV radiation. All sunscreen labels in the United States must state which rays they protect against. Products labeled with “broad protection” block both UVA and UVB.2 Sunscreen broad protection labeling is allowed only if the product has an SPF of at least 15. Sunscreen should no longer be labeled as “waterproof” and “sweat proof.” The product should only state if it is “water resistant.” The general recommendation is that everyone should use a sunscreen with a minimum SPF of 15 daily. Teach patients to look for the term broad spectrum on sunscreen packaging. Sunscreens with an SPF of 15 or more filter 92% of the UVB rays that are responsible for erythema, and make sunburn unlikely when applied appropriately. Patients who have a history of skin cancer or problems with sun sensitivity should use a product with an SPF of at least 30. Sunscreens should be applied 20 to 30 minutes before going outdoors, even in cloudy weather. The SPF value of all sunscreens decreases with time after application, and therefore sunscreen should be reapplied every 2 hours in a sufficient amount. One ounce per total body application is recommended. The ears, toes, and lips also need sunscreen. Sunscreens are not “waterproof” and should be reapplied immediately after swimming. Regular sunscreen use decreases the rate of developing melanoma.3 Certain topical and systemic medications potentiate the effect of the sun, even with brief exposure. Categories of drug therapy that may contain common photosensitizing medications are listed in Table 24-2. Be aware that many drugs are included in these categories. Examine the photosensitivity of each individual drug. The chemicals in these medications absorb light when exposed to natural sunlight and release energy that harms cells and tissues. The clinical manifestations of drug-induced photosensitivity (Fig. 24-1) are similar to those of exaggerated sunburn. These include swelling; erythema; vesicles; and papular, plaquelike lesions. Skin that is at risk for photosensitivity reactions can be protected by the use of sunscreen products. Teach patients who are taking these drugs about their photosensitizing effect. TABLE 24-2 DRUG THERAPY Patients can seek treatment for irritant or allergic dermatitis, which are two types of contact dermatitis. Irritant contact dermatitis is produced by direct chemical injury to the skin. Allergic contact dermatitis is an antigen-specific, type IV delayed hypersensitivity response. This response requires sensitization and occurs only in individuals who are predisposed to react to a particular antigen (see Chapter 14). • Vitamin A: Essential for maintenance of normal cell structure, specifically epithelial cells. It is necessary for normal wound healing. The absence of vitamin A causes dryness of the conjunctiva and poor wound healing. • Vitamin B complex: Essential for complex metabolic functions. Deficiencies of niacin and pyridoxine (B6) manifest as dermatologic symptoms such as erythema, bullae, and seborrhea-like lesions. • Vitamin C (ascorbic acid): Essential for connective tissue formation and normal wound healing. Absence of vitamin C causes symptoms of scurvy, including petechiae, bleeding gums, and purpura. • Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol): Essential for bone health. It is produced naturally by cutaneous photosynthesis after UVB exposure. A deficiency manifests as bone and muscle weakness and pain. • Vitamin K: Essential for synthesizing blood clotting factors. A deficiency interferes with normal prothrombin synthesis in the liver and can lead to bruising. • Protein: Necessary in amounts adequate for cell growth and maintenance. It is also necessary for normal wound healing. • Unsaturated fatty acids: Necessary to maintain the function and integrity of cellular and subcellular membranes in tissue metabolism. Linoleic and arachidonic acids are particularly important. Obesity has adverse effects on the skin. The increase in subcutaneous fat can lead to stretching and overheating (see Chapter 41). Overheating secondary to the greater insulation provided by fat causes increased sweating, which inflames and dries the skin. Obesity is also a risk factor for poor wound healing. Obesity can be associated with the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus, which may cause skin symptoms such as velvety dark skin of neck and body folds (acanthosis nigricans), rash in intertriginous sites (intertrigo), skin tags (acrochordons), and impaired arterial and venous flow (see Chapter 49). Skin cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer.4 Skin cancers are either nonmelanoma or melanoma. A persistent skin lesion that does not heal is highly suspicious for malignancy and should be examined by a health care provider. Early detection and treatment can often lead to a highly favorable prognosis. The fact that skin lesions are so visible increases the likelihood of early detection and diagnosis. Teach patients to self-examine their skin at least on a monthly basis. The cornerstone of skin self-examination is the ABCDE rule,5 which is easy to teach and remember. Examine skin lesions for Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color change and variation, Diameter of 6 mm or more, and Evolving in appearance (Fig. 24-2). Emphasize that lesions once flat and now raised, or once small and recently growing or changing in appearance, are warning signs and should be examined by a health care provider. Risk factors for skin malignancies include having a fair skin type (blond or red hair and blue or green eyes), history of chronic sun exposure, family history of skin cancer, and exposure to tar and systemic arsenicals.6 Environmental factors that increase the risk of skin malignancies include living near the equator, outdoor occupations, and frequent outdoor recreational activities. Behavioral factors such as using indoor tanning booths and outdoor sunbathing are controllable risk factors for skin malignancies. Patients treated with oral methoxsalen (psoralen) and psoralen plus ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) may be at greater risk for melanoma. Nonmelanoma skin cancers, either basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma, are the most common forms of skin cancer.7 More than 2.2 million new cases are diagnosed every year. Nonmelanoma skin cancers develop in the epidermis. They do not develop from melanocytes, the skin cells that make melanin, as melanoma skin cancers do. The most common sites for the development of nonmelanoma skin cancer are in sun-exposed areas, such as the face, head, neck, back of the hands, and arms. Actinic keratosis, also known as solar keratosis, consists of hyperkeratotic papules and plaques on sun-exposed areas. Actinic keratoses are premalignant skin lesions that affect nearly all of the older white population. These are the most common of all precancerous skin lesions. The clinical appearance of actinic keratoses can be highly varied. The typical lesion is an irregularly shaped, flat, slightly erythematous papule with indistinct borders and an overlying hard keratotic scale or horn (Table 24-3). TABLE 24-3 PREMALIGNANT AND MALIGNANT CONDITIONS OF THE SKIN 5-FU, Fluorouracil; PUVA, psoralen ultraviolet A; UVB, ultraviolet B.

Nursing Management

Integumentary Problems

Health Promotion

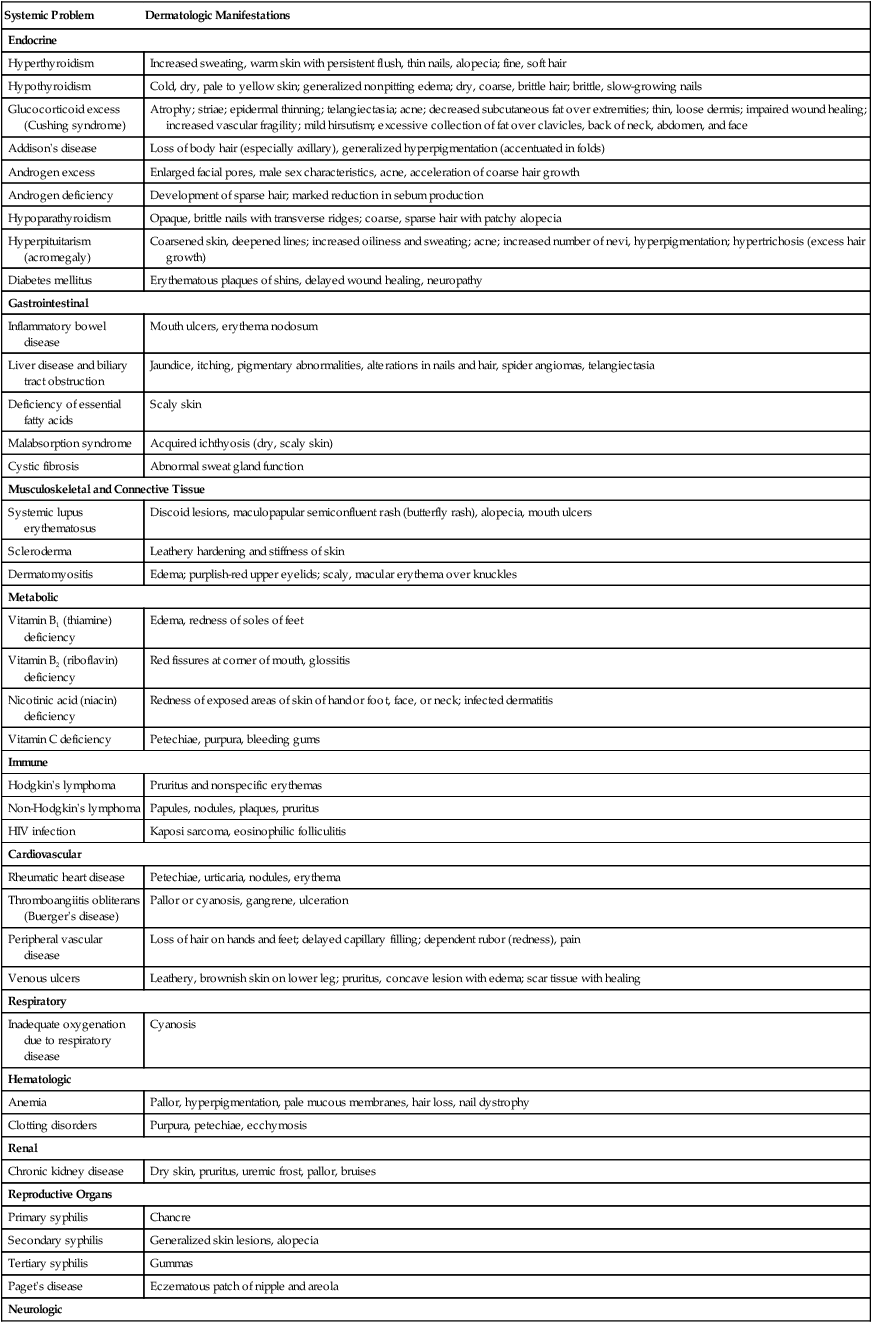

Systemic Problem

Dermatologic Manifestations

Endocrine

Hyperthyroidism

Increased sweating, warm skin with persistent flush, thin nails, alopecia; fine, soft hair

Hypothyroidism

Cold, dry, pale to yellow skin; generalized nonpitting edema; dry, coarse, brittle hair; brittle, slow-growing nails

Glucocorticoid excess (Cushing syndrome)

Atrophy; striae; epidermal thinning; telangiectasia; acne; decreased subcutaneous fat over extremities; thin, loose dermis; impaired wound healing; increased vascular fragility; mild hirsutism; excessive collection of fat over clavicles, back of neck, abdomen, and face

Addison’s disease

Loss of body hair (especially axillary), generalized hyperpigmentation (accentuated in folds)

Androgen excess

Enlarged facial pores, male sex characteristics, acne, acceleration of coarse hair growth

Androgen deficiency

Development of sparse hair; marked reduction in sebum production

Hypoparathyroidism

Opaque, brittle nails with transverse ridges; coarse, sparse hair with patchy alopecia

Hyperpituitarism (acromegaly)

Coarsened skin, deepened lines; increased oiliness and sweating; acne; increased number of nevi, hyperpigmentation; hypertrichosis (excess hair growth)

Diabetes mellitus

Erythematous plaques of shins, delayed wound healing, neuropathy

Gastrointestinal

Inflammatory bowel disease

Mouth ulcers, erythema nodosum

Liver disease and biliary tract obstruction

Jaundice, itching, pigmentary abnormalities, alterations in nails and hair, spider angiomas, telangiectasia

Deficiency of essential fatty acids

Scaly skin

Malabsorption syndrome

Acquired ichthyosis (dry, scaly skin)

Cystic fibrosis

Abnormal sweat gland function

Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue

Systemic lupus erythematosus

Discoid lesions, maculopapular semiconfluent rash (butterfly rash), alopecia, mouth ulcers

Scleroderma

Leathery hardening and stiffness of skin

Dermatomyositis

Edema; purplish-red upper eyelids; scaly, macular erythema over knuckles

Metabolic

Vitamin B1 (thiamine) deficiency

Edema, redness of soles of feet

Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) deficiency

Red fissures at corner of mouth, glossitis

Nicotinic acid (niacin) deficiency

Redness of exposed areas of skin of hand or foot, face, or neck; infected dermatitis

Vitamin C deficiency

Petechiae, purpura, bleeding gums

Immune

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Pruritus and nonspecific erythemas

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Papules, nodules, plaques, pruritus

HIV infection

Kaposi sarcoma, eosinophilic folliculitis

Cardiovascular

Rheumatic heart disease

Petechiae, urticaria, nodules, erythema

Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease)

Pallor or cyanosis, gangrene, ulceration

Peripheral vascular disease

Loss of hair on hands and feet; delayed capillary filling; dependent rubor (redness), pain

Venous ulcers

Leathery, brownish skin on lower leg; pruritus, concave lesion with edema; scar tissue with healing

Respiratory

Inadequate oxygenation due to respiratory disease

Cyanosis

Hematologic

Anemia

Pallor, hyperpigmentation, pale mucous membranes, hair loss, nail dystrophy

Clotting disorders

Purpura, petechiae, ecchymosis

Renal

Chronic kidney disease

Dry skin, pruritus, uremic frost, pallor, bruises

Reproductive Organs

Primary syphilis

Chancre

Secondary syphilis

Generalized skin lesions, alopecia

Tertiary syphilis

Gummas

Paget’s disease

Eczematous patch of nipple and areola

Neurologic

Chronic sensory polyneuropathies

Spinal cord trauma

Trophic changes in skin resulting from sensory denervation, pressure ulcers, anesthesia, paresthesias

Environmental Hazards

Sun Exposure.

Wavelength

Effect

Long (ultraviolet A [UVA])

Can produce elastic tissue damage and actinic skin damage. Contributes to formation of skin cancer.

Middle (ultraviolet B [UVB])

Causes sunburn and cumulative effect of sun damage. Major factor in development of skin cancer.

Short (ultraviolet C [UVC])

Does not reach earth, since it is blocked by atmosphere.

Drugs That May Cause Photosensitivity

Categories

Examples

Anticancer drugs

methotrexate, vinorelbine (Navelbine)

Antidepressants

amitriptyline (Elavil), clomipramine (Anafranil), doxepin (Sinequan)

Antidysrhythmics

quinidine, amiodarone (Cordarone)

Antihistamines

diphenhydramine (Benadryl), chlorpheniramine, clemastine (Tavist)

Antimicrobials

tetracycline, sulfamethoxazole, azithromycin (Zithromax), ciprofloxacin (Cipro)

Antifungals

griseofulvin, ketoconazole (Nizoral)

Antipsychotics

chlorpromazine (Thorazine), haloperidol (Haldol)

Diuretics

furosemide (Lasix), hydrochlorothiazide (HydroDIURIL)

Hypoglycemics

tolbutamide (Orinase), glipizide (Glucotrol), chlorpropamide (Diabinese)

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs

diclofenac (Voltaren), piroxicam (Feldene), sulindac (Clinoril)

Irritants and Allergens.

Nutrition

Malignant Skin Neoplasms

Risk Factors

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers

Actinic Keratosis

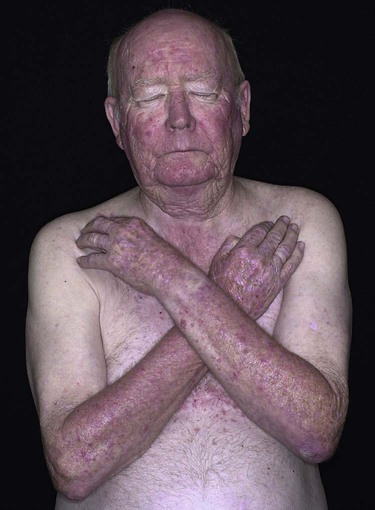

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Clinical Manifestations

Treatment and Prognosis

Actinic Keratosis

Actinic (sun) damage. Premalignant skin lesions. Common in older whites.

Flat or elevated, dry, hyperkeratotic scaly papule. Possibly flat, rough, or verrucous (wartlike). Adherent scale, which returns when removed. Often multiple. Rough scale on red base. Often on erythematous sun-exposed area. Increase in number with age.

Cryosurgery, chemical peels, laser resurfacing, topical application of 5-FU over entire area for 14-28 days or topical application of imiquimod (Aldara) for 16 wk, photodynamic therapy followed by light irradiation. Recurrence possible even with adequate treatment.

Atypical or Dysplastic Nevi

Morphologically between common acquired nevi and melanoma. May be precursor of malignant melanoma.

Often >5 mm. Irregular border, possibly notched. Variegated color of tan, brown, black, red, or pink within single mole. Presence of at least one flat portion, often at edge of mole. Frequently multiple. Most common site on back, but possible in uncommon mole sites such as scalp or buttocks (Fig. 24-3).

Increased risk for melanoma. Careful monitoring of persons suspected of familial tendency to melanoma or dysplastic nevi. Excisional biopsy for suspicious lesions.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Change in basal cells. No maturation or normal keratinization. Continuing division of basal cells and formation of enlarging mass. Related to excessive sun exposure, genetic skin type, x-ray radiation, scars, and some types of nevi.

Nodular and ulcerative: Small, slowly enlarging papule. Borders semitranslucent or “pearly,” with overlying telangiectasia. Erosion, ulceration, and depression of center. Normal skin markings lost (see Fig. 24-2).

Superficial: Erythematous, pearly, sharply defined, barely elevated plaques.

Surgical excision, chemosurgery, electrosurgery, chemotherapy, cryosurgery. 90% cure rate. Slow-growing tumor that invades local tissue. Metastasis rare. 5-FU and imiquimod for superficial lesions, photodynamic therapy for small lesions, vismodegib (Erivedge) for metastatic or recurrent locally invasive lesions.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Frequent occurrence on previously damaged skin (e.g., from sun, radiation, scar). Malignant tumor of squamous cell of epidermis. Invasion of dermis, surrounding skin.

Superficial: Thin, scaly erythematous plaque without invasion into the dermis.

Early: Firm nodules with indistinct borders, scaling and ulceration (see eFig. 24-1).

Late: Covering of lesion with scale or horn from keratinization, ulceration. Most common on sun-exposed areas such as face and hands.

Surgical excision, cryosurgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, electrodesiccation and curettage. Untreated lesion may metastasize to regional lymph nodes and distant organs. High cure rate with early detection and treatment.

Malignant Melanoma

Neoplastic growth of melanocytes anywhere on skin, eyes, or mucous membranes. Classification according to major histologic mode of spread. Potential invasion and widespread metastases.

Irregular color, surface, and border. Variegated color, including red, white, blue, black, gray, brown. Flat or elevated. Eroded or ulcerated. Often <1 cm in size. Most common sites in males are back, then chest. In females are legs, then back (see Fig. 24-2).

Surgical excision and possible sentinel lymph node evaluation depending on the depth. Correlation of survival rate with depth of invasion. Poor prognosis unless diagnosed and treated early. Spreading by local extension, regional lymphatic vessels, and bloodstream. Possible use of adjuvant therapy after surgery if lesion >1.5 mm in depth.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

Origination in skin. Localized chronic, slowly progressing disease. Possibly related to environmental toxins and chemical exposure. Mycosis fungoides (MF) is most common form. Sézary syndrome is an advanced form of MF. Prevalence twice as high in men as in women in United States.

Classic presentation involves three stages—patch (early), plaque, and tumor (advanced). History of persistent macular eruption followed by gradual appearance of indurated erythematous plaques on the trunk that appear similar to psoriasis. Pruritus, lymphadenopathy.

Treatment usually controls symptoms, not curative. UVB, PUVA, corticosteroids, topical nitrogen mustard, radiation therapy in patch and plaque stage disease. Interferon, systemic chemotherapy, extracorporeal photopheresis, romidepsin (Istodax) for progressive disease. Bexarotene (Targretin), denileukin diftitox (Ontak), and vorinostat (Zolinza) for advanced disease. Disease course is unpredictable, 10% will have progressive disease.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Nursing Management: Integumentary Problems

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access