Seriously and Persistently Mentally Ill, Homeless, or Incarcerated Clients

Hundreds of thousands of vulnerable Americans are eking out a pitiful existence on city streets, under ground in subway tunnels, or in jails and prisons due to the misguided efforts of civil rights advocates to keep the severely mentally ill out of hospitals and out of treatment.

It is estimated that there are approximately 9 million people incarcerated in prisons worldwide, with 2 million in the United States. An exhaustive research of 62 psychiatric surveys of 22,790 prisoners found that psychiatric disorders are much more prevalent in the prison population than in the general population.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Articulate the effect of a serious and persistent mental illness on the life of a client so affected.

Discuss the relationship between serious and persistent mental illness and the problems of homelessness and incarceration.

Explain how deinstitutionalization, transinstitutionalization, and lack of community services have contributed to the current problems of those with serious and persistent mental illness.

Describe the groups of individuals comprising the homeless population.

Identify those clients with serious and persistent mental illness who are at risk for incarceration.

Compare and contrast mental health and social service treatments for nursing-home residents, the homeless, and the incarcerated who are experiencing serious and persistent mental illness.

Articulate the impact of managed care on the mental health treatment and continuum of care of those with serious and persistent mental illness.

Discuss the effect of a member of the family having serious and persistent mental illness.

Summarize important nursing assessments for the client with serious and persistent mental illness.

Determine nursing implementations that are important for a client with serious and persistent mental illness.

Construct a nursing plan of care for a client with serious and persistent mental illness.

Key Terms

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) model

Clubhouse program

Deinstitutionalization

Empowerment Model of Recovery

Hate crime

Impulse control disorders

Integrated Model Program (IMPACT)

Mercy bookings

Respite care for the homeless

Serious and persistent mental illness (SPMI)

Transinstitutionalization

Welcome Home Ministries

Serious and persistent mental illness (SPMI), also referred to as severe and persistent mental illness, is the current accepted term denoting a variety of psychiatric–mental health problems that lead to tremendous disability. Although commonly associated with illnesses such as schizophrenia, the term SPMI includes people with wide-ranging psychiatric diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, severe major depression, substance-related disorders, and personality disorders) persisting over long periods (ie, years) and causing disabling symptoms that significantly impair functioning.

The symptoms of SPMI can be ongoing throughout the lives of some individuals, whereas others may experience periods of remission. Every aspect of living can be affected by the illness, including family and social relationships, physical health status, the ability to obtain employment and housing, and even the ability to accomplish routine activities of daily living. Persons with SPMI are often shunned by society and isolated from the community. Their behavior is often bizarre, including such actions as responding to hallucinations by shouting in public or talking or gesturing to themselves. Their appearance may be disheveled because hygiene and other self-care activities are neglected due to the severity of the symptoms. Often, these persons are unable to live independently and need assisted-living situations. Such clients go through the revolving doors of acute psychiatric care. They may be sent to group homes, to one of the few remaining state institutions, or to jails, or they may become homeless. Understanding this population and their special problems and needs is important for the psychiatric–mental health nurse.

This chapter focuses on the role of the psychiatric–mental health nurse and the application of the nursing process related to the current needs of individuals with SPMI. These clients often have coexisting problems such as homelessness, a dual diagnosis, or involvement with the judicial system.

Scope of Serious and Persistent Mental Illness

According to the World Health Organization, major depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and substance-related disorders account for four of the ten leading causes of disability globally. Each year, approximately 23% of American adults are diagnosed with a psychiatric–mental health disorder, and 5.4% of these adults are said to be seriously and

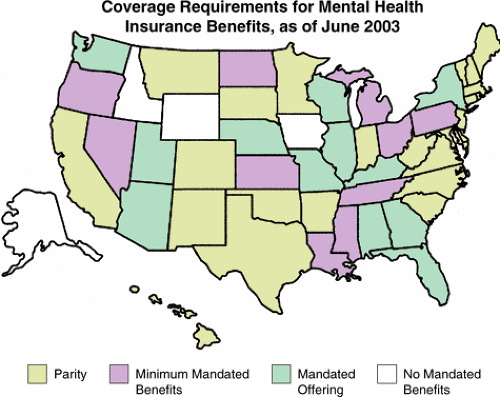

persistently mentally ill (Medscape Resource Center, 2004). The association of SPMI with poverty and poor health care creates a need for comprehensive psychiatric–mental health care and the use of social services to address issues related to independent living. Factors such as substandard housing, unemployment or underemployment, poor nutrition, lack of preventive care, and limited access to medical care create severe stressors for individuals affected with mental illness (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Figure 35-1 shows the states that provide some form of insurance benefits for mental illness as of June 2003. At the time of publication, four states had no laws addressing mental health insurance coverage: Idaho, Wyoming, Iowa, and Alaska.

persistently mentally ill (Medscape Resource Center, 2004). The association of SPMI with poverty and poor health care creates a need for comprehensive psychiatric–mental health care and the use of social services to address issues related to independent living. Factors such as substandard housing, unemployment or underemployment, poor nutrition, lack of preventive care, and limited access to medical care create severe stressors for individuals affected with mental illness (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). Figure 35-1 shows the states that provide some form of insurance benefits for mental illness as of June 2003. At the time of publication, four states had no laws addressing mental health insurance coverage: Idaho, Wyoming, Iowa, and Alaska.

The physical health of individuals with SPMI is worse than the physical health of those without SPMI. Poor living conditions related to the failure to provide for basic needs in a stable environment contribute to this poor physical health status. In fact, people with SPMI die an average of 10 to 15 years earlier than the general population. Unhealthy lifestyle habits, excessive smoking, lack of physical exercise, and poor nutrition contribute to the increased health risk. Fifty percent of people with SPMI are estimated to have a known comorbid medical disorder (Farnam, Zipple, Tyrell, & Chittinanda, 1999).

Factors Related to the Current Problems of the Seriously and Persistently Mentally Ill

Three factors have contributed to the current problems associated with SPMI. These factors, complex and related to the history of psychiatric–mental health treatment over the last several decades, include deinstitutionalization, transinstitutionalization, and the lack of community services to provide for the multiple needs of the seriously and persistently mentally ill.

Deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization, the process by which large numbers of psychiatric–mental health clients were discharged from public psychiatric facilities during the last 40 years, created an influx of seriously and persistently mentally ill clients sent back into the community to receive outpatient care. Deinstitutionalization is a major factor in the current problems of the mentally ill. Since 1960, more than 90% of state psychiatric hospital beds have been eliminated. This process began in 1955, and accelerated with the Civil Rights legislation of the 1960s as well as the withdrawal of federal-government financing for state-hospital clients in the 1970s (see Chapter 8). See Clinical Example 35-1 for an example.

Transinstitutionalization

Transinstitutionalization is the process of transferring state-hospital clients to other facilities. Nursing-home placement and incarceration remain a significant component of transinstitutionalization. According to Andrew Sperling, director of policy for the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), it appears that there are still a large number of people with SPMI being placed in nursing homes (MacNeil, 2001). Furthermore, America’s jails and prisons are now surrogate psychiatric hospitals for thousands of individuals with the most severe brain diseases (Treatment Advocacy Center [TAC], 2003).

Self-Awareness Prompt

Think about a client you have met with serious and persistent mental illness. Did the client have any physical health problems? Was the client compliant with treatment recommendations? How would you rate the client’s living situation? What interventions would you plan for the client?

Inappropriate Use and Lack of Community Services

The initial plans for deinstitutionalization involved federal funding for community mental health centers with the goal of providing early diagnosis and timely treatment in a community setting, rather than in large state hospitals removed from the community. The belief was that these mental health centers would eliminate the need for state hospitals. However, cost shifting by the federal government to state governments for these mental health centers led to inadequate and insufficient money for treatment. In addition, issues of insufficiently trained personnel and funding mechanisms were not addressed (Smoyak, 2000). Large numbers of clients who were

deinstitutionalized were actually transferred to nursing homes and other similar institutions. Those who did not qualify for nursing-home care were released to hastily established group homes, boarding homes, personal-care facilities, or the streets. Today, funding for aftercare community services continues to decline (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

deinstitutionalized were actually transferred to nursing homes and other similar institutions. Those who did not qualify for nursing-home care were released to hastily established group homes, boarding homes, personal-care facilities, or the streets. Today, funding for aftercare community services continues to decline (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Clinical Example 35.1: A Client After Deinstitutionalization

EM was among the large population of clients released from state hospitals from 1960 to 1980. Hospitalized since adolescence, she was in her thirties when released and was unable to function in society. Without family support and lacking fundamental resources or employment skills, she became permanently dependent on social services. EM was admitted to the hospital after police were called by her landlord and neighbors, who complained that she was knocking on doors in the middle of the night and threatening people with harm. Her apartment contained large amounts of trash and was infested with cockroaches. The landlord began eviction proceedings soon after she was hospitalized. This was her 16th hospital admission for mental illness.

Categories of Seriously and Persistently Mentally Ill Clients

The categories of seriously and persistently mentally ill clients who provide challenges to the psychiatric–mental health nurse include nursing-home residents, the homeless, and the incarcerated. Each group is discussed below.

Nursing-Home Residents

An act of Congress and a Supreme Court decision to perform pre-admission screening and resident reviews (PASRRs) prior to admission have not stopped the inappropriate placement of mentally ill adults into nursing homes that do not provide psychiatric services (see Chapter 8). According to the Inspector General’s office, there are people in nursing homes who are seriously and persistently mentally ill (eg, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and personality disorder) and in need of more than casual mental health services. For example, 3.8% of clients with chronic schizophrenia reside in nursing homes (Begley, 2002). Researchers in San Diego found that although older people with schizophrenia did not have more physical illnesses than non–mentally ill people in the same age range, their illnesses were often more severe (Cohen, 2001). Of the top primary diagnoses at the time of admission for nursing-home residents, mental disorders ranked second (17%) only to diseases of the circulatory system (27%) (Clinical Psychiatry News, 2001).

Federal agencies have accepted state recommendations to improve nursing-home admission criteria for clients with mental illness and to provide appropriate mental health services. However, the individual states must agree to initiate programs (eg, availability of on-site mental health services and reimbursement for services) and remove certain barriers for reform to occur (MacNeil, 2001).

The Homeless

Homeless individuals and families are those who are sleeping in places not meant for human habitation (eg, cars, parks, sidewalks, or abandoned buildings) or who sleep in emergency shelters as a primary nighttime residence. Other individuals may be considered homeless if they:

Live in transitional or supportive housing

Ordinarily sleep in transitional or supportive housing but are spending 30 or fewer consecutive days in a hospital or other institution

Are being evicted within a week from a private dwelling and without resources to obtain access to alternative housing

Are being discharged from an institution in which they resided for more than 30 consecutive days and without resources to obtain access to alternative housing (United States Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2002)

Although several national estimates are available about homelessness, many are dated or are based on dated information. By its very nature, homelessness is impossible to measure with 100% accuracy. Researchers use different methods to measure homelessness. One method, point-in-time counts, attempts to count all the people who are literally homeless on a given day or during a given week. A second method, period prevalence

counts, attempts to count the number of people who are homeless over a given period of time. The high turnover in the homeless population documented in various studies suggests that many people experience homelessness but do not remain homeless. For example, over time some people will find housing and escape homelessness, whereas new people will lose housing and become homeless (National Coalition for the Homeless [NCH], 2005a).

counts, attempts to count the number of people who are homeless over a given period of time. The high turnover in the homeless population documented in various studies suggests that many people experience homelessness but do not remain homeless. For example, over time some people will find housing and escape homelessness, whereas new people will lose housing and become homeless (National Coalition for the Homeless [NCH], 2005a).

Recent studies suggest that the United States generates homelessness at a much higher rate than had been previously thought. The best approximation of homelessness is from an Urban Institute study in the year 2000, which states that about 3.5 million people—1.35 million of them children—are likely to experience homelessness in a given year (NCH, 2005a).

Clients deinstitutionalized from 1970 through the 1990s often ended up homeless due to lack of adequate psychiatric–mental health and social services. Statistics released by the Treatment Advocacy Center in 1999 indicate that 200,000 individuals with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder are homeless. In addition, the loss of state hospital beds caused a significant portion of the population with SPMI, who would have been in state hospitals, to become homeless. Homelessness among those with SPMI usually occurs as a result of several factors, including lack of family involvement, inability to pay rent, bizarre behaviors, and commitment to a psychiatric institution. A new wave of deinstitutionalization, and the denial of services or premature and unplanned discharge brought about by managed care arrangements, also may be contributing to the continued presence of the homeless population (NCH, 2005b).

Risk Factors for Homelessness

Several risk factors have been described for homelessness among persons with SPMI (Caton & Shront, 1994). These include:

Presence of positive symptoms of schizophrenia

Concurrent drug or alcohol abuse

Presence of a personality disorder

High rate of disorganized family functioning from birth to age 18

Lack of current family support

See Clinical Example 35-2 for an example.

Clinical Example 35.2: The Homeless Client With SPMI

DN was removed from her parents’ home at the age of 8 after physical and sexual abuse. She lived in five different foster homes until the age of 15, when she was placed in a group home. At age 17, she ran away from the group home and lived on the streets or in shelters in between the times she was hospitalized. DN’s situation includes risk factors for homelessness, including the presence of positive symptoms of schizophrenia (hallucinations and delusions), a personality disorder, and a chaotic family experience until age 18.

Although mental illness can precipitate homelessness, the crisis of being homeless can also compound the problem of mental illness. That is, the stressors of not being able to meet basic needs, and of being exposed to the elements and other risks to safety such as violence, can all increase the severity and persistence of mental illness.

Special Populations of the Homeless

Health care providers today are confronted with the changing face of the homeless. Following is a list of the groups that comprise the homeless (NCH, 2005c):

39% of children under the age of 18 years; 42% of these children were under the age of 5 years

25% ages 25 to 34 years

6% were ages 55 to 60 years

41% were single men and 14% were single women

49% were African American; 35% Caucasian, 13% Hispanic, 2% Native American, and 1% Asian

Veterans (approximately 40% of the homeless population)

HIV/AIDS victims (approximately 3%–20% of the homeless population)

Domestic-violence victims (approximately 50% of all women and children experiencing homelessness are fleeing domestic violence.)

Substance abusers (unable to estimate due to refusal to admit to illegal use of substances)

23% of individuals who are diagnosed as SPMI

The rates of both chronic and acute health problems are extremely high among the homeless, who are far more likely to suffer from every category of chronic health problem. In addition, the problems associated

with homelessness, although affecting every aspect of living, can have specific consequences depending on the age and gender of the individual affected.

with homelessness, although affecting every aspect of living, can have specific consequences depending on the age and gender of the individual affected.

Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults

Numerous psychiatric–mental health problems that manifest in adolescence and young adulthood have their roots in early childhood. Studies have also shown that an important risk factor for infants and children is the occurrence of psychopathology in the primary caregivers (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [ODPHP], 1998). For example, preschool and school-age children of women who are homeless and mentally ill are at high risk for physical and emotional illnesses, as well as developmental delays. Poor nutrition, chronic stress of the caregiver who is homeless, and lack of access to preventive health care are contributing factors. The adolescent population is at high risk for being physically and sexually abused. They are also at high risk for using drugs and alcohol to cope with homelessness.

Women

Women who are homeless have often experienced domestic violence. When mental illness is present, the combination of the illness and lack of adequate resources is a causative factor in homelessness. A history of unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, and the risk for rape and violence, also are common in homeless women.

The Elderly

The elderly, although constituting a small percentage of the homeless population, generally have problems related to dementia often caused by chronic use of substances. A study of elderly homeless men identified that this population was poorer, in poorer health, and more likely to have alcohol-use disorders than their younger counterparts (DeMallie, North, & Smith, 1997).

Hate Crimes Against the Homeless

Hate crime is defined by the U.S. Congress as a crime in which the defendant intentionally selects a victim (or in the case of a property crime, the property that is the object of the crime) because of the victim’s race, color, or national origin.

The federal law to combat hate crimes (Title 18 U.S.C. §245) was passed in 1968. It mandated that the government must prove both that the crime occurred because of a victim’s membership in a designated group and because the victim was engaged in certain specified federally protected activities (eg, serving on a jury, voting, attending public school). Federal bias crime laws such as the Hate Crimes Statistics Act of 1990 and the Hate Crimes Sentencing Enhancement Act of 1994 further clarified the definition of hate crime by stating that the crime occurs because of “actual or perceived race, color, national origin, ethnicity, gender, disability, or sexual orientation of any person” (NCH, 2006).

During the last several years, advocates and homeless-shelter workers have received news reports of homeless individuals, including children, being harassed, kicked, set on fire, beaten to death, and even decapitated. During the year 2005, a total of 86 hate crimes were committed in 22 states plus Puerto Rico. Of the 86 acts, 13 resulted in death. Ages of the victims ranged from 22 to 70 years. The age range of the perpetrators of the hate crimes ranged from 13 to 75 years. A majority of the victims (62) were male (NCH, 2006).

Most hate violence is committed by individual citizens who harbor a strong resentment toward a certain group of people; who violently act out their resentment toward the perceived growing economic power of a particular racial or ethnic group; or who take advantage of vulnerable and disadvantaged persons to satisfy their own pleasure. Teens who are “thrill seekers” are the most common perpetrators of violence against the homeless (NCH, 2006). See Chapter 33 for additional information regarding hate crimes.

The Incarcerated

The process of deinstitutionalization has also resulted in a significant population of clients with SPMI being maintained in jails and prisons. Since the 1970s, when state mental institutions were closed, correctional facilities now house more individuals with SPMI than ever before (Yurkovich, Smyer, & Dean, 2000). According to a study by the Human Rights Watch, jails and prisons have become the nation’s default mental health system. Approximately 400,000 Americans in jail and prison (compared with 300,000 in 1999) have SPMI—more than four times the number in state mental institutions. The percentage of female inmates who are mentally ill is considerably higher than that of male inmates (Butterfield, 2003). Moreover, according to one estimate, more than 40% of persons with a mental illness have been arrested at least once. Additional statistics comparing the seriously and persistently mentally ill incarcerated population with the general prison population were reported by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2001):

One of eight state prisoners received mental health counseling or therapy by mid-2000.

Offenders between the ages of 45 and 54 years were most likely to be identified as seriously and persistently mentally ill.

Mentally ill state prison inmates were twice as likely as general population inmates to have lived in a shelter within the last year.

50% of mentally ill offenders reported having three or more prior sentences.

33% of mentally ill federal inmates were convicted of a violent offense, compared with 13% of general population inmates.

53% of mentally ill state inmates were convicted of a violent offense, compared with 46% of general population inmates.

10% of state prisoners received psychotropic medication.

50% of state prison facilities provided mental health services.

66% of hospitalized state prisoners who were released obtained mental health services.

Factors Related to Incarceration

Those with psychiatric–mental illness are often incarcerated because community-based programs are non-existent, are filled to capacity, or are inconveniently located. Other factors include the failure to address clients’ mental health problems and obstacles to commitment to psychiatric care by the legal structure. Persons with a mental illness are incarcerated for overt, aggressive behavior caused by psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions; vagrancy; trespassing; disorderly conduct; alcohol-related charges; or failure to pay for a meal. Generally, the offense leading to incarceration occurs as a result of either the effect of the mental illness itself or the problem of mental illness coexisting with a substance-abuse disorder. See Clinical Example 35-3.

Mercy bookings, defined as arrests made by police to protect individuals with SPMI, are surprisingly common. This is especially true for women, who are easily victimized, even raped, on the streets (TAC, 2003).

The jails and prisons lack necessary services for effective treatment of the mentally ill, and thus have become warehouses for those with nowhere else to go. In a National Institute of Justice survey, prison administrators described their mental health programs as grossly understaffed and in urgent need of program development and intervention by mental health organizations (McEwen, 1995). Often, persons with mental illness remain incarcerated for longer periods of time than do persons without mental illness who are in prison for the same charges. Unfortunately, jails and prisons usually exacerbate the clinical symptoms of mental illness, either because individuals are not given the necessary medication to control their symptoms, or because they are placed in solitary confinement (TAC, 2003).

Clinical Example 35.3: The Client With SPMI Who Is Incarcerated

FR was never able to secure employment due to his SPMI and has depended on welfare and group-home living. He had a substance-abuse problem and when drinking would frequently destroy property or become involved in fights. Thus, he has a history of being incarcerated. FR also has a history of obesity and diabetes mellitus, has had one myocardial infarction, and continues to smoke and not manage his diabetes well.

Clients at Risk for Incarceration

Most crimes for which the seriously and persistently mentally ill are arrested are minor. However, some mentally ill offenders require incarceration to protect society. These offenders often include individuals with impulse control disorders, sexual disorders, substance-abuse disorders, bipolar disorders, personality disorders, and, as noted earlier, psychotic disorders.

The Client With an Impulse Control Disorder

Many psychological problems are characterized by a loss of control or a lack of control in specific situations. Usually this lack of control is part of a pattern of behavior that also involves other maladaptive thoughts and actions, such as substance abuse (Psychology Information Online, 2003).

Impulse control disorders are characterized by a person’s failure to resist an impulse despite negative consequences, thus not preventing oneself from performing an act that will be harmful to self or others. This includes the failure to stop gambling and the impulse to engage in violent behavior (eg, road rage), sexual behavior, fire starting, stealing, and self-abusive behavior. Researchers believe that impulse control problems may be related to functions in specific parts of the brain, and may be caused by a hormonal imbalance or the abnormal transmission of nerve impulses. Although the specific etiology is unknown, a person

who has had a head injury or the diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy is at higher risk for developing an impulse control disorder. Diagnosis is only made after all other medical and psychiatric disorders that might account for the symptoms have been ruled out (Psychology Information Online, 2003). Examples of impulse control disorders that often lead to incarceration are listed in Table 35-1.

who has had a head injury or the diagnosis of temporal lobe epilepsy is at higher risk for developing an impulse control disorder. Diagnosis is only made after all other medical and psychiatric disorders that might account for the symptoms have been ruled out (Psychology Information Online, 2003). Examples of impulse control disorders that often lead to incarceration are listed in Table 35-1.

| ||||||||||||

The Client With a Sexual Disorder

Individuals with the diagnosis of a sexual disorder may be incarcerated due to exhibitionism, voyeurism, rape, or pedophilic behavior. Alexander (1999) examined 79 studies covering 10,988 offenders who received outpatient treatment. Findings indicated that:

Treated offenders reoffended at a rate of 11% when compared with 17.6% of offenders who were not treated.

True incest offenders have lower reoffense rates when compared with other types of child molesters.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access