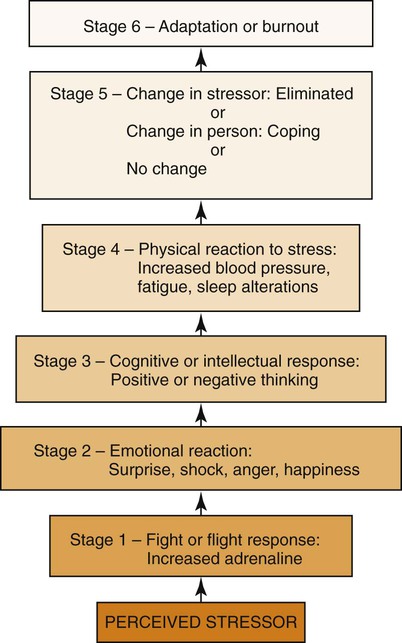

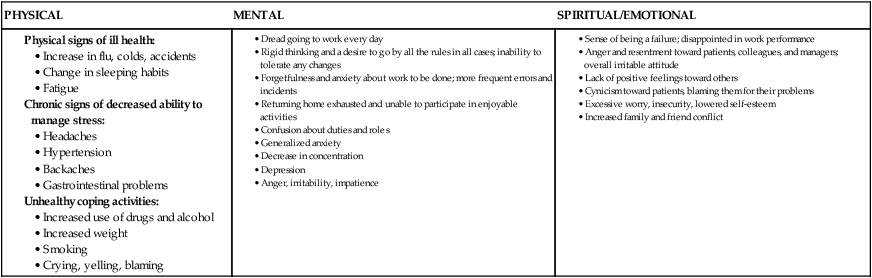

• Explore personal and professional stressors. • Analyze selected strategies to decrease stress. • Assess the manager’s role in helping staff manage stress. • Evaluate common barriers to effective time management. • Critique the strengths and weaknesses of selected time-management strategies. • Evaluate selected strategies to manage time more effectively. What should you do when you have tried your best, but things are not going well? What needs changing? Where do you begin? Self-management involves self-directed change to achieve important goals (Stuart & Laraia, 2008). As a nurse leader, your goals will require balancing personal and professional objectives and organizing your time and activities to reach them. The literature suggests that stress hardiness of nurse leaders is essential to safe, high-quality patient care (Halm et al., 2005), as well as staff recruitment and retention (Bailey, 2009). In the past, nursing research on stress focused on individual acceptance of demanding work environments, complex role requirements, and staff shortages instead of proactive problem solving (Shirey, 2006). Several thought leaders, reflected in the meta-analysis of Zangaro and Soeken (2007), suggest that cultivating stress hardiness produces nurse managers with a leadership style and resilience that improves working conditions. However, using both internally and externally available psychosocial resources did not compensate for the stress experienced by nurse managers and physicians (Lindholm, 2006). Luckily, stress hardiness can be taught (Judkins, Reid, & Furlow, 2006). Nurses have learned about the effect of stress on patients and how to teach them to manage its consequences. However, only one third of nurse managers have any sort of formal leadership or managerial training (Bailey, 2009) that would prepare them for dealing with multiple sources of stress at the same time. Nurses need to recognize the unique stressors in their professional and personal lives. Everyone experiences stress—the exhilaration of a joyous event, as well as the negative feelings and unpleasant physical symptoms that may be associated with a difficult life situation or even the anticipation of difficulty. Stress is the uncomfortable gap between how we would like our life to be and how it actually is. Nurses are not immune to the effects of stress. Learning what stress is, its dynamics, and some strategies to manage distress is a part of the personal and professional maturation of nurses. In this chapter, stress and distress (Selye, 1965) are used interchangeably, although some writers regard stress as neutral and refer to the positive and negative attributes of eustress and distress, respectively. Stress is a consequence or response to an event or stimulus. Stress is not inherently bad. It is each individual’s interpretation that determines whether the event is viewed as positive or threatening. In addition, stress management does not necessarily mean stress reduction. Rather, stress management is characterized by emotional and behavioral control, perseverance, and challenge in the face of stressful events (Kobasa, Maddi, & Kahn, 1982). Stress management is a nurse manager competency (Jennings, Scalzi, & Rodgers, 2007). Stress management has important implications for the workplace because of its link to low absenteeism rates, improved quality, and increased productivity (Judkins, Reid, & Furlow, 2006). Occupational stress in nursing has been well-defined and documented. Work-related stressors, such as workload, rotating shifts, high patient acuity, inadequate staffing, ethical conflicts, dealing with death and acute illness, role ambiguity, the intensity of complexity compression, and job insecurity have all been associated with increased stress and burnout. Nurses spend more time at work, and nurse managers report 12- to 14-hour days with 24-hour accountability (Rudan, 2002). Role stress is an additional stressor for nurses. Viewed as the incongruence between perceived role expectations and achievement (Chang & Hancock, 2003), role stress for new graduates is related to role ambiguity and role overload. Role stress is particularly acute for new graduates, whose lack of clinical experience and organizational skills, combined with new situations and procedures, may increase feelings of overwhelming stress. Conflict between what was learned in the classroom and actual practice may add additional stress. Approximately 94% of the nation’s 2.9 million nurses are women (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2005), and many go home to traditionally gender-related responsibilities that may include household management, children, and aging parents. When added to the already stressful workday of the nurse, the additional responsibilities often contribute to the level of distress felt by the nurse. Thanks to generation Y’s entry into the workforce, greater emphasis on work-life balance has become increasingly important. Evans and Steptoe (2002) examined the associations of work stress and gender-role orientation to psychological well-being and sickness-related work absences in male-dominated (accounting) and female-dominated (nursing) occupations in England. They concluded that when men and women are occupationally engaged in gender-dominated occupations in which they are in the gender minority, the men and women perceived more work-related hassles and exhibited gender-specific health effects. An individual’s ability to deal with stress may be moderated by psychological hardiness. According to Lambert, Lambert, and Yamase (2003), psychological hardiness is a composite of commitment, control, and challenge. These form a constellation that (1) dampers the effects of stress by challenging the perception of the situation and (2) decreases the negative impact of a situation by moderating both cognitive appraisal and coping. Maddi (2002), in a 12-year longitudinal study, found that individuals thriving in a stressful work environment displayed the same psychological hardiness. The commitment attitude led the individuals to be actively involved in the changes that decreased isolation. The control attitude led them to try to influence outcomes rather than sink into powerlessness and passivity. The challenge attitude led them to believe that the stressful events were opportunities for new learning. Stress may result from unrealistic or conflicting expectations, the pace and magnitude of change, human behavior, individual personality characteristics, the characteristics of the position itself, or the culture of the organization. Other stressors may be unique to certain environments, situations, and persons or groups. Initially, increased stress produces increased performance. However, when stress continues to increase or remains intense, performance decreases. Hans Selye’s mid-century investigations of the nature of and reactions to stress (Selye, 1956) have been very influential. In his classic theory, Selye (1991) described the concept of stress, identified the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), and detailed a predictable pattern of response (see the Theory Box on p. 556 and Figure 28-1). More recent investigations of the relationship among the brain, the immune system, and health (psychoneuroimmunology) have generated models that challenge Selye’s general adaptation syndrome. Although Selye states that all people respond with a similar set of hormonal and immune responses to any stress, Kemeny (2003) proposes that there are two stress responses: (1) the classic GAS and (2) a withdrawing reaction, in which the person pulls back to conserve energy. Kemeny hypothesizes that people respond to the same psychological event in different ways, depending on their independent appraisal of the situation (DeAngelis, 2002). Critical of stress research using predominately (87%) male subjects, Taylor et al. (2000) proposed a model of the female stress response, the “tend and befriend,” as opposed to the male’s “fight or flight” model. The “tend and befriend” response is an estrogen and oxytocin–mediated stress response that is characterized by caring for offspring and befriending those around in times of stress to increase chances of survival. Most nurses can easily recognize the origins of stress and its symptoms. For example, a healthcare agency may make demands on nurses, such as excessive work, that the nurses regard as beyond their capacity to perform. When they are unable to resolve the problem through overwork, with more staff, or by looking at the situation in another way, the nurses may feel threatened or depressed. They may also experience headache, fatigue, or other physical symptoms. If the stress persists, such symptoms may increase; nurses may attempt to cope by becoming apathetic or by resigning their positions. Table 28-1 gives physical, mental, and spiritual/emotional signs of overstress in individuals. TABLE 28-1 SIGNS OF OVERSTRESS IN INDIVIDUALS In 2004, Segerstrom and Miller published a meta-analysis of research on the relationship between stress and the human immune system. They found that acute stressors (very short-term) “revved up” the immune system, preparing for infection or injury. Short-term stressors, such as tests, tended to suppress cellular immunity while preserving humoral immunity. The immune systems of those who are older or already sick are more prone to stress-related immune system changes. One effective way to deal with stress is to determine and manage its source. Discovering the origin of stress in patient care may be difficult because some environments have changed so rapidly that the nursing staff is overwhelmed trying to balance bureaucratic rules and limited resources with the demands of vulnerable human beings. Complexity compression is the name given to conditions in which change occurs with great intensity (Krichbaum et al., 2007). When in distress, nurses may need to step back and look at the “big picture.” By identifying daily stressors, the nurse can then develop a plan of action for management of the stress. This plan may include elimination of the stressor, modification of the stressor, or changing the perception of the stressor (e.g., viewing mistakes as opportunities for new learning) using a reframing technique. According to Stöppler (2005), the top five stress-management mistakes are poor calendar habits, clutter, perfectionism, self-treatment, and following others’ expectations. These may be high on your list of stress experiences. Analyze your stress experiences by completing Exercise 28-1. Meditation to elicit the relaxation response can be beneficial. The benefits of practicing relaxation techniques for 20 minutes daily include a feeling of well-being, the ability to learn how tension makes the body feel, and the sense that tension can be controlled. In cases of some stress-related disorders (e.g., hypertension), biofeedback may be used to monitor physiologic relaxation processes. Exercise 28-2 outlines one systematic relaxation technique. Social support in the form of positive work relationships, as well as nurturing family and friends, may be an important way to buffer the negative effects of a stressful work environment (Erdwins, Buffardi, Casper, & O’Brien, 2001). Although friendships may be formed with colleagues, the workload and the shifting of staff from one unit to another often make it difficult to establish and maintain close relationships with peers. However, managers and co-workers who are supportive may improve morale in the workplace (Zangaro & Soeken, 2007) (see the Research Perspective at right). Nurses in a new position or in an unfamiliar geographic area must anticipate that they will benefit from the security of being part of a group that can furnish emotional support. Without easily accessible family and friends, nurses need to be intentional about seeking new, supportive personal relationships. Such efforts may help nurses cope with workplace demands that seem to exceed their capabilities. Positive coping strategies may also make nurses less likely to adopt such potentially negative coping strategies as withdrawing, lowering their standards of care, and abusing alcohol or other substances.

Self-Management

Stress and Time

Introduction

Understanding Stress

Definition

Sources of Job Stress

External Sources

The Position

Gender Roles

Internal Sources

Dynamics of Stress

Management of Stress

Stress Prevention

Symptom Management

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Self-Management: Stress and Time

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access