Robin Fleming*

School Health

Focus Questions

What is the history of school health nursing?

What can we learn from the past in defining the future of school nursing?

What are the eight components of a coordinated school health model?

How are school health programs organized and regulated?

What are the roles of the school nurse in the various components of school health?

What professional standards guide the practice of school nurses?

What are the future trends in school health?

How can schools contribute to the accomplishment of the objectives set forth in Healthy People 2020?

Key Terms

Comprehensive health education advisory committee

Comprehensive school health education

Coordinated school health program

Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA)

Handicapped Infant and Toddler Program

Healthy school environment

Individualized education plan (IEP)

Individualized family service plan

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

No Child Left Behind Act

Public Law 94-142

School-based health centers (SBHCs)

School health services

School nursing

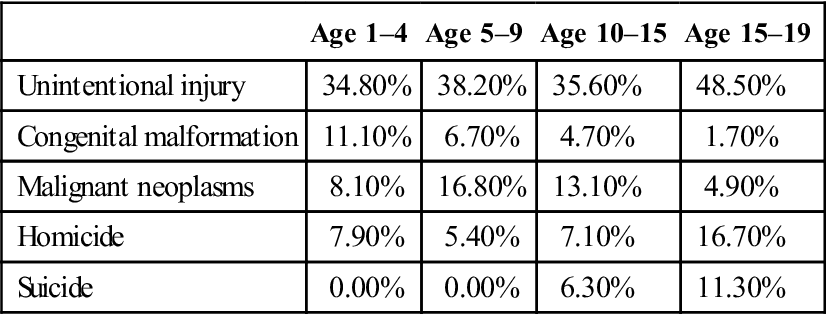

Health problems facing American children and adolescents have changed dramatically since World War II from those that primarily involved contagious diseases to problems that stem largely from complex sociocultural shifts, the passage of new federal and state laws, and historic increases in immigration. While mortality rates among children and teens have fallen dramatically during the past two decades, health risk behaviors that often occur in response to social and economic conditions, or that reflect developmental stages in children, continue to contribute to mortality and morbidity (Heron, 2010). As Table 30-1 illustrates, unintentional injuries are the leading cause of death for children in all age groups. As is evident from developmental and social perspectives, as children age, homicide and suicide pose greater risks for mortality, while deaths from malignant neoplasms peak between the ages of 5 and 15.

Table 30-1

Childhood Causes of Death by age – 2006

| Age 1–4 | Age 5–9 | Age 10–15 | Age 15–19 | |

| Unintentional injury | 34.80% | 38.20% | 35.60% | 48.50% |

| Congenital malformation | 11.10% | 6.70% | 4.70% | 1.70% |

| Malignant neoplasms | 8.10% | 16.80% | 13.10% | 4.90% |

| Homicide | 7.90% | 5.40% | 7.10% | 16.70% |

| Suicide | 0.00% | 0.00% | 6.30% | 11.30% |

Data from: Heron, M. (2010). Deaths: Leading causes for 2006. National Vital Statistics Reports, 58(14). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

High-risk behaviors that contribute to the leading causes of mortality include driving—or being a passenger in a car—after drinking alcohol. Use of alcohol or drugs and carrying weapons also are associated with higher rates of mortality (Eaton et al., 2010). There is an increasing trend in chronic health conditions in the young population. In a longitudinal study of chronic health conditions in children, Van Cleave and colleagues (2010) found an increased prevalence of obesity, asthma, and behavioral problems. The authors found the average prevalence of a chronic health condition in the population of children was 12.8 percent. Other studies confirm the persistence of chronic health conditions in children. Children who experienced activity limitations resulting from one or more chronic illnesses increased from 8% to 9% of the population between 2007 and 2008 (Childstats.gov, 2010). In that same time frame asthma and depression remained steady—8% of the child population, but obesity increased from 17% to 19%. Parents reported that 5% of children had serious behavioral, social, emotional, and/or attentional difficulties (Childstats.gov, 2010). The underlying causes for increases in childhood chronic health conditions can be traced to poverty, social inequalities, and improvements in medical technology that preserve the lives of pre-term infants and children born with other congenital abnormalities (Van Cleave et al., 2010). Individual behaviors such as drug, alcohol, and tobacco use and physical inactivity can contribute to or accentuate these chronic problems and/or deaths.

School nurses play a significant role in tending to the complex health needs of 75 million students in the United States. The National Association of School Nurses (NASN) defines school nursing as “a specialized practice of professional nursing that advances the well-being, academic success and life-long achievement and health of students. To that end, school nurses facilitate positive student responses to normal development; promote health and safety including a healthy environment; intervene with actual and potential health problems; provide case management services; and actively collaborate with others to build student and family capacity for adaptation, self-management, self advocacy, and learning” (NASN, 2011a).

Historical Perspectives of School Nursing

The historical roots of school nursing began in England and France in the mid-nineteenth century (Shipley Zaiger, 2000). In the United States, the high rate of student absenteeism, due primarily to infectious disease, was influential in the development of school nursing. In 1894, Boston established school health services to identify and exclude students with communicable diseases (Wold & Dagg, 1981). In 1902 a demonstration project, initiated by public health pioneer Lillian Wald in New York City, placed nurse Lina Rogers Struthers in a school where she was charged with reducing absences due to communicable disease (Hawkins et al., 1994; Schumacher, 2002; Vessey & McGowan, 2006). Within 1 year, school absences dropped by 90% (Kennedy, 2003). As a result, more school nurses were placed in the schools of New York, and the practice soon spread coast to coast, from Boston to Los Angeles (Vessey & McGowan, 2006).

The number of nurses practicing in schools throughout the nation increased as it became clear that contagious diseases were not the only ills needing attention. Physical disabilities, nutritional deficiencies, skin disorders, lice infestations, conjunctivitis, vision, hearing, and orthopedic concerns, and the physical and emotional consequences of child labor were other concerns (Fleming, 2005). These health issues expanded nursing practice from one that emphasized personal hygiene to one that included prevention, examination, treatment, and advocacy.

Socioeconomic and cultural forces during the great wars also influenced school nursing practice. Physical examinations were incorporated into school nurse practice during World War I to help ensure a steady supply of fit soldiers (Dilworth, 1944). After World War I, prevention grew in scope, was embedded in the school curriculum, and helped to solidify the partnership of educators and nurses working in an educational setting. School nurse practice shifted to prevention and early treatment of physical defects, as nearly 25% of men were rejected for military service during World War II (Palmer, 1944). Emphasis on prevention expanded to include vision, hearing, and orthopedic screenings.

School nursing became more public health oriented during the 1940s and 1950s as approximately half of all community/public health nurses were employed in school health at that time (Wold & Dagg, 1981). A public health orientation emphasized a more family-centered approach to care as nurses provided health guidance and consultation with an emphasis on health promotion. The health team, a collaboration between nurses and teachers, evolved during this same period.

The concept of the school nurse practitioner, developed in 1970, allowed for an expansion of the nurse’s skills in the areas of history taking, physical appraisal, and developmental assessment (Igoe, 1975). Emphasis was placed on primary care in the school setting and community involvement in program development (Hawkins et al., 1994). School-based health centers grew rapidly from their initial introduction in the late 1960s and expanded in the 1990s (Gustafson, 2005). Today, school nurses have expanded their scope of practice to manage the more complex health problems of some students and to be instrumental in integrating new health care delivery models into the school setting (Lear, 2002).

Since the early 1900s, the development of school health has been influenced by multiple external forces. These forces have included developments within public health, nursing, pediatrics, education, and the political arena. Social and legislative initiatives have also shaped the development of this specialty. All of these factors continue to influence the scope of school nursing practice. The future of school nursing will depend on the ability of nurses to respond to new opportunities and changing political and funding environments while providing quality care to school-aged children.

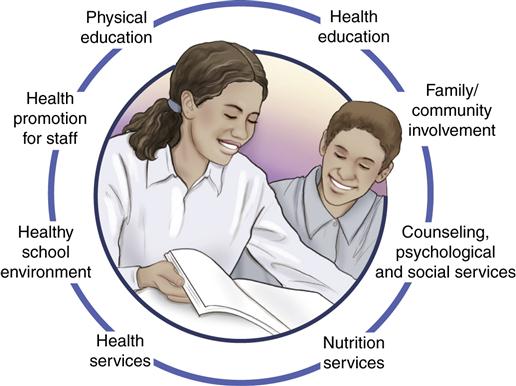

Components of Coordinated School Health

The roles of the school nurse and the school health team have evolved based on the changing needs of children, adolescents, and teens. The traditional school health approach in the 1980s encompassed three domains: clinical health services, health education, and promoting a healthy and safe school environment. While these domains remain relevant today, more specific objectives to meeting them are articulated within a broader approach that advocates a more comprehensive coordinated school health program, a position supported by the National Association of School Nurses (2008) (Figure 30-1). Some of the objectives of Healthy People 2020 (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010) support school-based health education, health promotion, physical activity, and improved clinical care services (see the Healthy People 2020 box on page 751-752).

The coordinated school health program consists of a broad spectrum of eight school-related activities and services. They are: 1) Health education; 2) Physical education; 3) Health services; 4) Mental health and social services; 5) Nutrition services; 6) Healthy and safe environment; 7) Family and community involvement; and 8) Staff wellness (Allensworth & Kolbe, 1987; Joint Consortium for School Health, 2011). The definitions of these components are presented in Table 30-2 and are described in the following sections.

Table 30-2

Definitions of the Components of a Coordinated School Health Program

| Component | Definition |

| Health education | A planned, sequential, K-12 curriculum that addresses physical, social, mental, and emotional dimensions of health. |

| Physical education | A planned, sequential K-12 curriculum to address physical fitness, movement, rhythms, dance, sports (individual, dual, and team), tumbling and gymnastics, and aquatics. |

| Health services | Services to students to appraise, protect, and promote health. These are designed to ensure access or referral to primary care, prevent and control disease and health problems, provide emergency care, provide a safe environment, and provide educational and counseling opportunities for promoting health. |

| Nutrition services | Access to a variety of nutritious, appealing meals that meet the health and nutrition needs of students. |

| Health promotion for staff | Activities focused on improving the health of faculty/staff through assessments, health education, and health-related physical activities. |

| Counseling and psychological services | Services to improve students’ mental, emotional, and social health. |

| Health school environment | Physical and aesthetic surroundings and the psychosocial climate and culture of the school. |

| Parent/community involvement | An integrated approach that would include school health advisory councils, coalitions, and constituencies to build the program. |

Adapted from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). About the program: School health defined. Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/Healthyyouth/CSHP/.

Health Education

Health education is defined as a distinct academic discipline that influences, and seeks the improvement of, individual, family, and community health (American Association for Health Education [AAHE], 2009). The American Association for Health Education (2003) prioritizes 10 health education content areas: community health, consumer health, environmental health, family life, mental and emotional health, injury prevention and safety, nutrition, personal health, prevention and control of disease,

and substance use and abuse. Key elements of comprehensive school health education include:

• a curriculum that addresses and integrates education about a range of categorical health problems

• activities that help young people develop skills to avoid health problems

• instruction for a prescribed amount of time at each grade level

• management and coordination by an education professional

• instruction from teachers who are trained to teach the subject

• involvement of parents, health professionals, and community members

• periodic evaluation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2008a)

Progress toward comprehensive school health programs and policies is monitored in the School Health Policies and Programs Study 2006 (SHPPS) (Kann et al., 2006). SHPPS is the largest and most comprehensive study of school health policies and programs at the state, district, school, and classroom levels nationwide. Data were collected in 1994, 2000, and 2006. The eight core components of a coordinated school health program, and the progress made toward meeting goals of these components within the context of Healthy People 2020 objectives, are reflected in SHPPS’s most recent 2006 analyses, and are highlighted below.

Comparing data gathered in 2000 to that collected in 2006 finds progress made in regard to the core components of comprehensive school health as stressed in Healthy People 2020. An overall improvement was seen in the proportion of middle, junior high, and senior high schools providing health education in some content areas from a baseline of 30.7% in 2000 to 43.6% in 2006. Of the 10 specific health education content areas identified by Healthy People 2020 as priorities, only two failed to make progress in the SHPPS report: tobacco use and addiction, and alcohol and other drug use.

Improvements have been made in both middle and high schools with regard to teaching about human sexuality and pregnancy prevention and in the percentage of school districts that required elementary schools to teach about injury prevention and safety from 66.2% in 2000 to 77.4% in 2006. For middle schools, this requirement jumped from 66.7% to 80.3%, perhaps reflecting districts’ understanding of the threat to youth of injury and the importance of health education in helping to reduce this threat. Conversely, while violence is a leading contributor to youth morbidity and mortality, particularly at the high school level, school districts reduced the number of hours that violence prevention was taught, from 4.9 hours in 2000 to 2.6 hours in 2006 in elementary schools, and from 4.1 to 2.5 hours in high schools.

Both content and quality of health education are important if the curricula are to be adopted and will encourage student retention of the material. National Health Education Standards (NHES) guide schools and school districts in selecting and developing curricula, instruction, and student assessment in health education (CDC, 2007a). The percentage of states that adopted a policy mandating schools and districts to follow national or state health education standards or guidelines increased from 60.8% to 74.5% between 2000 and 2006 (Kann et al., 2006). In addition, NHES’s recommend curricular topics—injury prevention, drug and alcohol use or abuse, and sexuality related sequelae—were taught to students at all levels in the majority of states, districts, and schools. While Kann and colleagues were hopeful about the progress made implementing health curricula, they note there is still a need for teacher staff development to maximize curricular delivery and student learning. Only 25.5% of teachers delivering required health curricula received training on any of the 14 identified health topics. In addition, since the 2006 study results were released, the United States has undergone an economic recession that has resulted in cutbacks to education and to the elimination of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Division of Adolescent and School Health (DASH).

Health Curricula

Health curricula traditionally have been organized around broad content areas. An additional focus is on teaching students critical coping skills aimed at improving healthy behaviors and reducing unhealthy ones. Strategies are geared toward negating harmful media messages and emphasizing skills that promote adoption of health-enhancing behaviors (refusal skills, problem solving, decision making, media analysis, assertiveness skills, communication, coping strategies for stress, and behavioral contracting).

State education agencies and local school districts can use the national standards to make decisions about which lessons, strategies, and activities to include in health curricula. The majority of states and districts require instruction in certain topics. These topics include accident or injury prevention, prevention of alcohol and other drug use, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection prevention, healthy nutritional and dietary behavior, physical activity and fitness, pregnancy prevention, sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention, suicide prevention, tobacco use prevention, and violence prevention (CDC, 2005).

Over 80% of states and districts require schools to teach health education at all three levels—elementary, middle/junior high, and senior high. A comprehensive school health program using these standards will most likely show evidence of the following:

• Health content that is introduced in the early grades and reinforced in later grades

• Student assessments that measure skill acquisition as well as knowledge

• Use of performance indicators that define what a student is able to do at different grade levels

• Provision of a minimum of 50 hours of health education at every grade level

Curriculum planning and development should accommodate the unique local needs and preferences of each community. This is a critical step in increasing support from and awareness of the community. Lohrmann and Wooley (1998) have suggested that several steps can be implemented to achieve this support: 1) creating a comprehensive health education advisory committee that includes parent representation; 2) holding awareness sessions for the school board, school staff, and community members; and 3) developing a plan for funding that involves school personnel, families, students, related community agencies, and businesses.

Curriculum Implementation

Implementing a curriculum for health education requires teaching strategies that are effective in increasing knowledge, changing attitudes, and influencing health-related behavior. Suggested strategies include the following:

• The use of discovery approaches, with opportunities for hands-on experiences

• The use of student learning stations, small work groups, and cooperative learning techniques

• Cross-age and peer teaching, especially regarding drug use

• An emphasis on the affective domain (e.g., self-esteem and self-efficacy)

The use of information technologies as a teaching tool, team building and collaborative planning between elementary teachers and colleagues, and strategies that foster family involvement in students’ health education help improve the effectiveness of health education (Lohrmann & Wooley, 1998).

Physical Education

Physical activity promotes positive health behaviors and psychological well-being. Regular physical activity decreases premature mortality and risk of chronic disease. The benefits of regular physical activity include building and maintaining healthy bones, reducing the risk of developing obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and other chronic illnesses, and reducing feelings of depression and anxiety (CDC, 2006a). Several Healthy People 2020 objectives emphasize the importance of physical education in schools to promote and sustain physical activity. The data from the 2006 SHPPS study indicates that states, districts and schools are attempting to improve efforts to increase physical activity of youth. Problems remain in establishing criteria to ensure quality when implementing physical activity curricula. The 2006 SHPPS study found over 70% of states and districts had policies in place to teach physical education using national or state physical education standards but few schools provided daily physical education (Lee et al., 2007). In addition, many states, districts, and schools allowed exemptions for physical education, and some schools continued to use physical exercise as a means of punishment. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2010a) reported that in 2007 only about 35% of students in grades 9 through 12 met recommended levels of physical activity and only 30% attended daily physical education classes. While recognizing the gains in physical activity between 2000 and 2006, Lee and colleagues (2007) recommended comprehensive approaches for physical activity parameters at all school levels.

According to standards developed by National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) (2011) students should be able to meet the following standards:

• Participate regularly in physical activity

• Achieve and maintain a health-enhancing level of physical fitness

• Value physical activity for health, enjoyment, challenge, self-expression, and/or social interaction

Schools can use the Physical Education Curriculum Analysis Tool developed by the CDC to help assess the extent to which their curricula reflect the national physical education standards of the NASPE.

Health Services

Health services are critically important to the welfare of students as well as to the educational mission of schools. Important functions of school health services include the following (CDC, 2010b):

Models for health services vary depending on the needs of the students and the resources available in the school and community. Models of care that are used in schools today are school nurse services and or school nurse services combined with services offered through school-based health centers (SBHCs). The roles of school nurses and of school-based health providers are distinct and complementary, and best serve children when they act collaboratively. There are currently an estimated 45,000 school nurses employed in the United States, serving 49.5 million children in grades K through 12 (American Federation of Teachers [AFT], 2007), which results in a ratio of one school nurse per 1155 students. The ratio recommended by NASN (2010a) is one nurse for every 750 regular education students; 1:225 in student populations requiring daily professional school nursing services; 1:125 in student populations with complex health care needs; and 1:1 for individual students who require daily and continuous professional nursing services. The NASN advocates for each school in the United States to have a full-time school nurse every day (Trossman, 2007).

While school nurses serve entire school populations and provide important gatekeeping functions, school-based health centers (SBHCs) provide comprehensive care, primarily related to reproductive health, mental health, and primary care services. The number of SBHCs has increased from 200 in 1990 to approximately 1900 centers across the country located in 45 states and the District of Columbia (Strozer et al., 2010). SBHCs exist in part in response to meeting the needs of the nation’s 11 million uninsured, and 14 million underinsured, children (Kogan et al., 2010). These clinics tend to care for poor and ethnic minority populations. They are staffed by a variety of medical providers, including nurse practitioners and mental health counselors, and serve all school grade levels, with most services targeting the needs of high school students (Strozer et al., 2010). The majority of SBHCs—80%—are able to bill for services rendered, unlike school nurses, who must rely primarily on state funding and grants, which are subject to economic vagaries.

Nutrition Services

Healthy eating in children and adolescents is essential for positive growth and development, intellectual development, and prevention of nutrition-related health problems, such as obesity, iron deficiency anemia, dental caries, and eating disorders. The essential functions of school nutrition services are to provide adequate access to a variety of culturally and nutritionally appropriate foods, to provide nutrition education to empower students as consumers, and to assess and intervene when nutritional problems are identified. Nutrition services must be integrated in the school, encouraging communication among health services, the cafeteria, and the classroom with input also from the physical education staff, families, and community organizations (CDC, 2007b).

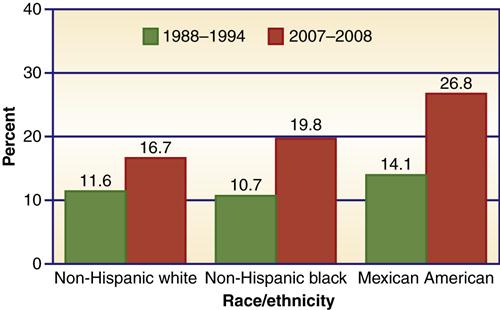

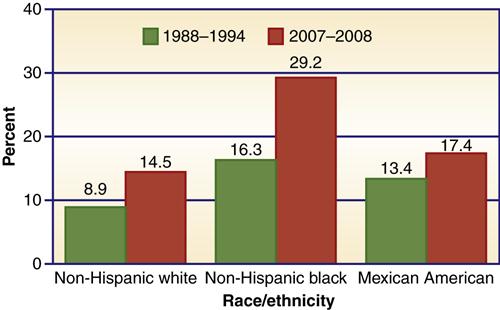

In 2011 the CDC reported that 17% of children (12.5 million) ages 2 to 19 in this country are obese, three times the rate of obesity in 1980 (CDC, 2011a; Ogden et al., 2006). Data from the 2009 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicated the prevalence of obesity in children of all ages and obesity increased with age (CDC, 2009a). The very young (2 to 5 years) had double the obesity rate of that in 1980, and those between 6 and 18 had tripled the rate of obesity found in 1980 (Ogden & Carroll, 2010). In 2009 overweight children represented 15.8% of the child population according to the biannual Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (CDC, 2009a). There are racial and ethnic disparities in obesity rates. Black and Hispanic children of both genders had higher rates of obesity prevalence than white children (Figure 30-2). Between 1999 and 2000 and 2007 and 2008, there appears to be a leveling off of the spiraling obesity trend perhaps due to the national emphasis on this issue.

The YRBS (CDC, 2009a) reported a modest but steady increase in consumption of fruit juices and a decrease in consumption of soda pop by children in grades 9 to 12. Intake of fruits and vegetables has remained steady, showing no improvement between 1999 and 2009 (CDC, 2009a).

Research has attempted to determine the causes of, and effective responses to, improving the nutritional status of Americans and of American children. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (2008) found people with higher educational levels were more likely to consume fruits and vegetables than those with lower educational levels and education has a more pronounced influence on consumer food choices than does income. This puts schools and school health providers in an excellent position to educate students at all grade levels about the comparatively lower cost of choosing nutrient-dense foods over foods high in fats, simple sugars, and calories. Consumer knowledge about the nutritional content of foods increases the likelihood that people will choose a variety of foods, emphasizing those that have higher nutritional value. Because children help influence family food selection, nutrition education at school may ultimately be a powerful way to help reverse the epidemic of overweight and obesity that threatens the nation’s health.

During the 1990s, schools began to offer competitive food products in addition to the school meal program. Competitive foods met student preferences and gained added revenue for school food services since some food services must be self-supporting. It also allowed food services additional discretionary income (for example contracts with soft-drink companies) and met student needs when food preparation and serving space was limited and meal periods were too short to allow students to eat a full meal (CDC, 2009b). Food delivery options include vending machines, school stores, snack bars, and à la carte foods in the cafeteria. Competitive foods have been found to be low in nutritional density and high in fat, sugar, and calories; the availability of competitive foods tends to stigmatize participation in the school meal program and can affect the viability of these programs. In addition, the availability of competitive foods conveys a mixed nutritional message when children are taught the value of healthy food choices.

The NASN encourages school nurses to provide nutrition education and role modeling and to work with schools, parents, and the community to send a consistent message by providing healthy foods and beverages in all school vending machines, school stores, and snack bars (NASN, 2007). Since the problems with competitive foods have been exposed (e.g., increasing obesity rates and lower consumption of nutritional foods), measures have been taken to ensure that competitive foods have high nutritional values and that these offerings are consistent with a school culture that promotes health and healthful eating. States have made progress in eliminating unhealthy foods in schools and replacing them with healthier options. From 2002 to 2008, the percentage of schools in which students were not able to purchase candy or high-fat salty snacks increased in 37 of 40 states surveyed (CDC, 2009c). From 2006 to 2008, the percentage of schools in which students could not purchase soda pop or fruit drinks that were not 100% juice increased in all 34 participating states (CDC, 2009c). Despite these improvements, there continues to be wide state variability in allowing student access to sports beverages, soda pop, candy, and salty snacks (CDC, 2009c). School nurses should work collaboratively with school officials and other public health professionals to limit the availability of sugary and fatty snacks to students, as recommended by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2007a).

Counseling, Psychological, and Social Services

Mental health affects overall physical health as well as academic achievement, and the increasing rates of mental heath problems in the school-age population is a growing concern. The leading mental health disorders experienced by school-age children and adolescents are mood and anxiety disorders. Mental health problems in school children are addressed later in this chapter. If available, mental health services may be fully integrated into the school or may be offered in the context of primary health care in SBHCs. An expanded school mental health framework includes prevention, assessment, treatment, and case management of students in special and general education (Stephan et al., 2007). Services provided at school help to reduce stigma around seeking treatment for mental health concerns, and reduce cost and transportation barriers that can occur outside the school setting. Services may be focused on individuals, groups, or institutions (school environment). Nurses, certified school counselors, psychologists, and social workers provide these services in schools.

Healthy School Environment

The healthy school environment contains both physical and psychosocial aspects. The school environment includes the nation’s 120,000 public and private school buildings, school grounds and surrounding areas, and all locations where school-related events and activities take place. This environment includes physical conditions such as noise, sanitation, temperature, heating, and lighting. It also includes personal safety, as well as safety surrounding sports, building events, extracurricular activities, and transportation. Several excellent tools are accessible online to assist schools in promoting a safe environment. The Healthy School Environments Assessment Tool from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2011) contains multiple resources schools can use to improve environmental and building safety, as well as links to information regarding state and local requirements and policies (EPA, 2011). Healthy Schools Network is a national organization that works to ensure a healthy school environment for every child and has suggestions for assessments and interventions (Healthy Schools Network, 2010).

Common asthma triggers at schools include poor ventilation, the presence of high levels of dust mites and mold spores in buildings, perfumes and sprays, and even cleaning agents used to rid buildings of asthma triggers (EPA, 2010). Box 30-1 lists common sources of allergens in classrooms. The Community Resources for Practice section at the end of the chapter provides resources for nurses and school personnel interested in learning more about healthy school environments, including resources on drinking water, pest management, air quality, and environmental education.

A healthy psychosocial school environment encompasses both physical and psychological safety, and includes elements that address reducing use of tobacco or substances at school or school-sponsored events, as well as addressing issues that interfere with students’ sense of personal safety. Bullying and violence at schools are actions that can have significant effects on students’ well-being and safety. Schools should have policies in place to prevent and address bullying and violence, both on school grounds and via cyberspace, where bullying is less likely to be detected by adults. School staff and administrators also should be cognizant of child populations that are at greater risk of becoming victims of violence and bullying. Students who identify as, or who are perceived as gay, bisexual, or transgender, are at much greater risk of being harassed or victimized (Mental Health America, 2011). School nurses and other school-based health providers are in optimal positions to educate staff and communities, and to support students, in creating a school environment that is free of physical and social harms. The CDC has developed guidelines to prevent unintentional injuries and violence at school. Box 30-2 lists the recommendations.

Health Promotion for Staff

In 2008, 9.5 million adults were employed by public school systems in the United States; 6.3 million of them were teachers (U.S. Department of Education [USDE], 2010). Working to promote and protect the health of staff is an important contribution of the school nurse. Health-promotion activities improve productivity, increase staff morale, decrease absenteeism, and reduce health insurance costs (School Employee Wellness, 2011). Healthy staff members are excellent role models for students. Some examples of staff health-promotion activities include maintaining a health-promotion library stocked with books on stress, conducting on-site smoking cessation classes with a quitters’ support group, and holding classes on defensive driving, first aid, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The Directors of Health Promotion and Education, in cooperation with several other agencies, have developed the manual School Employee Wellness: A Guide for Protecting the Assets of Our Nation’s Schools, which includes tools and resources to help schools develop their own staff wellness programs. The manual and other information sheets can be downloaded free from http://www.schoolempwell.org.

Family/Community Involvement

Schools are not isolated entities. Enhancing the health of students requires an integrated approach in working with families and communities. Support for a school health program can be obtained through the efforts of school health advisory councils, coalitions, and broadly based constituencies for school health. SHPPS found that 72.9% of districts and 39.5% of schools have school health councils (Kann et al., 2006). The CDC (1997) has identified principles of community engagement important to establishing and promoting success of community-led efforts and programs. Among the principles necessary to promoting success of these partnerships are cultural awareness, mutual respect and trust, identifying and mobilizing community assets, and maintaining flexibility to accommodate changing community needs. Epstein and colleagues (2009) have created a useful research-based handbook to guide schools, parents, and community partners in determining best how to plan, implement, evaluate, and improve family and community interactions with schools. Another useful resource that provides strategies on engaging culturally diverse families with schools is Diversity: School, Family, and Community Connections, produced by the National Center for Family and Community Connections with Schools (2003).

Organization and Administration of School Health

Most nations have centralized school systems in which a national ministry prescribes curricula. That is not the case in the United States, where public education is decentralized.

Patterns of Organization and Management of School Health Programs

Education is primarily the responsibility of local and state governments. The federal government enacts laws that impact education, but provides little of the funding for educational programs. School health is also, for the most part, a local and state responsibility.

At the local level, each school adopts, implements, and organizes the components of a coordinated school health program. This usually involves a multidisciplinary team, including the school nurse, health educator, physical educator, school counselors, physical therapist, speech therapist, school social workers, school psychologists, food service staff, parents, police liaisons, clerical staff, bus drivers, custodial staff, and older students. Teachers, support staff, and representatives of community organizations are equally important as partners in the development and implementation of a coordinated school health program.

The school health program needs the support of the local community and school district. To guarantee long-term sustainability, support from the leadership in the district and the school board is key. Programs will differ from school to school and district to district. Each district will have certain mandated elements (e.g., vision and hearing screening, physical education), and other components dictated by the child’s age, the environment, and geographical location. Other elements will be identified, modified, or emphasized based on the individual school’s health team assessment.

The organizational component of nursing services varies among schools and districts. Community/public health nurses in school health settings are most often employed by a school district, a board of education, or board of health. In addition, nurses hired through a board of health may be assigned to specialized services in schools or to generalized nursing services with occasional assignments in the school setting. Other approaches to hiring include the use of agency nurses to fill school nurse positions, the hiring of school nurses by parent/teacher/student associations, contracting with local hospitals and health maintenance organizations, and the assignment of special project nurses funded by private or government grants. Because the school nurse serves autonomously in the school setting, the integrity of this specialty practice is best preserved when hiring agents conform to school nurse standards set by nurse practice acts, nursing laws, and recommendations made by leading professional organizations in school health. Whatever the hiring entity, the school nurse maintains accountability both to school administrations as well as to the organization responsible for her or his hiring.

Legislative and Administrative Regulations

School health programs vary markedly across the United States, and are influenced at the local, state, and federal levels. Federal requirements focus on protecting children, families, and employees, and on providing services to children with disabilities (CDC, 2008b; Lear, 2002; Thackaberry, 2003). Schools must report school safety statistics, and funding under the federal Safe and Drug-Free Schools and Communities program must be used to implement effective drug-and violence-prevention programs. The most salient federal laws governing school health programs include the following:

• Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970

• Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Section 504

• Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) of 1974

• Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) of 1975

• Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990

• Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) imposes requirements on the workplace to promote safety for employees, including school employees. In the schools, requirements include implementation of the following (U.S. Department of Labor, 2007):

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Public Law 93-112) protects the rights of individuals with disabilities to participate in programs that receive federal money. The Office of Civil Rights is responsible for overseeing compliance with Section 504. The law ensures that federally assisted programs and activities are operated without discrimination on the basis of disabilities and that reasonable accommodations are made for the disability of students and employees (see Chapters 26 and 27). A free and appropriate education must meet the individual needs of students who qualify as handicapped and can consist of special or regular education. A disability covered by Section 504 must be severe enough to result in the student’s having a substantial limitation in carrying out one or more major life activities (e.g., breathing, walking, talking, seeing, and hearing), having a record of having such an impairment, or being regarded as having such an impairment (Lear, 2002; Moses et al., 2005; Thackaberry, et al., 2003).

In 1975 the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA), known as Public Law 94-142, was enacted. This law gives all students between 6 and 18 years of age the right to a “free and appropriate public education” in the least restrictive environment possible, regardless of their physical or mental disabilities. The 1986 amendments to the EHA contained in Public Law 99-457 expanded the eligible population to include preschool students from birth to 5 years of age. This law created two new federal programs: the Handicapped Infant and Toddler Program and the Preschool Grants Program. The Handicapped Infant and Toddler Program, for children from birth to 3 years of age, was established to reduce the potential for developmental delays, minimize institutionalization of children with disabilities, help families meet the special needs of their children, and reduce the cost to society. Under the Preschool Grants Program, state educational agencies must provide free and appropriate education for all children with disabilities beginning at age 3 years (USDE, 2011a).

In 1990, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA; Public Law 105-17) succeeded the EHA. In 1997 Congress passed amendments to the IDEA further defining responsibility of school districts to provide disabled students aged 3 to 21 years the right to participate in the general curriculum. These called for the development of an individualized education plan (IEP) for each student with a disability that identifies the special education and related services the student needs. There are 6.8 million children and youth with disabilities served under IDEA (USDE, 2011b). Because most children with IEPs have physical, cognitive, or emotional health issues that qualify them for special education, school nurses are essential in informing IEPs and in developing accompanying individual health plans (IHPs) to meet these students’ health needs and educational objectives (Fleming, 2011). In 2004 the IDEA was reformed to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEIA). School districts must continue to educate disabled children in the least restrictive environment possible, keeping them in regular classrooms if it does not interfere with their educational performance (NASN, 2006). When special education services are needed, a multidisciplinary team including the school nurse meets to determine eligibility and necessary services. The health services necessary for a child to participate safely and fully in the school are determined by, and are reflected in, an IEP for children aged 5 to 21 years, and in an individualized family service plan for children aged 3 to 5 years (NASN, 2006). Many school districts face seemingly insurmountable tasks in meeting their legal responsibilities for providing related services to the 6.5 million U.S. school-aged children with disabilities (USDE, 2011b), primarily due to lack of funding. Clear documentation of the specific needs of the student in the IEP is imperative, and parents and schools must become partners in developing strategies for increased funding to provide services for students. Interdisciplinary and interagency collaboration must be achieved, and new, creative planning must be accomplished to use all school and community resources to help students with disabilities feel valued as members of the community. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 extends the Public Accommodation Act to include individuals with disabilities. This allows people with disabilities to have equal access to and opportunity to use and enjoy facilities and programs. This act extends the requirements to some private school health programs and provides coverage to children who were not included in Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (Lear, 2002).

Confidentiality of school records is ensured under the Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). FERPA protects the privacy of student records by limiting access to parents, students over age 18 or emancipated minors, and educators who have a legitimate educational interest. FERPA privacy provisions also address the need to keep records in locked cabinets, to protect computer records with passwords, and to be vigilant about the illegal use of health sign-in logs (CDC, 2008b; Thackaberry, 2003). School nurses must be aware of the laws and use judgment in recording information obtained from the student. It should be noted that school-based health clinic and health center records, records connected with treatment of a student in a federally assisted program for drug or alcohol abuse, and records connected with child abuse or neglect are not considered part of the education records.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) protects the privacy of an individual’s health information, including name, medical diagnoses, and treatment. All records from SBHCs fall directly under HIPAA regulation. There continues to be concern and clarification about the interaction between HIPAA and FERPA, which regulates information such as immunization records and records of mandated physical examinations (Bergren, 2004; Cohn, 2007; USDE, 2007). All schools do exchange information with multiple health care providers who must meet HIPAA requirements. Therefore, the release of information forms should meet the HIPAA criteria, including closely defined use of the permission form, ability to revoke the permission form, and limitation on who can receive the information. The nurse must protect information that allows the client to be identified in written, verbal, and electronic transfer of information (Schwah, 2005).

The federal No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 has several major provisions that focus on increasing accountability for student progress and achievement. It does so primarily by requiring schools to demonstrate academic progress (via “high-stakes” standardized testing) or lose federal funding or face other sanctions. Because the law focuses exclusively on academic progress to determine whether, and how much, funding schools receive, it encourages schools and districts to funnel resources in ways that limit support for necessary yet indirect influences on academic outcomes. This has resulted in diminished support for health services, which are shown to promote student retention rates and improve learning readiness and academic performance (Constante, 2006; Hanson et al., 2004).

State laws vary. Some mandated responsibilities of health service programs include overseeing school entrance requirements (immunizations and physical examinations), performing health screenings, developing nursing care plans for children with disabilities, and providing emergency care. State statutes frequently are recommended by the health department and enforced by the local school administration and the health department. Other examples of state requirements include Board of Nursing registered nurse (RN) licensure and, when relevant, school nurse and health education certification. Each state requires the reporting of suspected child abuse.

Most states identify health services that can be delegated to nonnursing staff members. School personnel, by and large, have no training in health-related fields and generally don’t anticipate having to perform health care functions when they accept employment as teachers or school employees (Taliaferro, 2005). Because lack of funding impedes the presence of full-time nurses at many school buildings, school nurses must train and delegate some tasks to unlicensed school staff. State laws and nurse practice acts vary on which tasks are delegable. Tasks that generally cannot be delegated are those that require nursing judgment, including administration of some medications such as insulin and Diastat (Fleming, 2011). Addressing how to improve student safety by placing full-time nurses in all school buildings is an initiative being led by the NASN.

Responsibilities of the School Nurse

The scope of practice of school nursing has been significantly influenced by economic and social changes, legislation that mandates increased school nurse assessment and health planning practices, widespread lack of health coverage, and increasing numbers of children with health concerns. Nurses who practice school nursing acquire the philosophy, goals, qualifications, and specific education unique to this specialty. The NASN (2003a) recommends that all school nurses receive at minimum a four-year baccalaureate degree and receive national school nurse certification.

A new paradigm for school nursing is emerging, one that recognizes the complexity of the practice and its importance in promoting population health, academic achievement, and reducing health and educational disparities. To meet these objectives, this expanded role includes program management, interdisciplinary collaboration, health education and counseling, school-community coordination, enhanced clinical and assessment skills, and research.

Educational Preparation and Certification

School nurses should have academic credentials comparable to those of other faculty members in the school. The NASN (2003a) advocates that the minimum qualification for an entry-level professional school nurse position is a four-year baccalaureate degree and licensure as an RN. Nurses in certain states also need to meet state certification requirements. The National Board for Certification of School Nurses (NBCSN) offers a voluntary national certification examination for school nurses that confirms that the nurse meets a national standard of preparation, knowledge, and practice in the field of school nursing. Eligibility to take the examination requires a current RN license, a bachelor’s degree, current employment in school health services or school-related services, and a recommended 3 years of experience as a school nurse (NBCSN, nd).

Advanced practice RNs provide valuable services to students through expanded school health services. Clinical nurse specialists in community health with organizational and policy skills have the ability to assess, implement, and evaluate school health programs. School nurse practitioners and pediatric nurse practitioners have the ability to diagnose and manage most common illnesses and provide primary health care on site at the school. The NASN supports these advanced practice roles to broaden the health service so that more health needs are met and the education of the students is thereby improved (NASN, 2003b).

Standards of Practice

School nurses are professionals who are accountable for practicing in accordance with the Standards of Professional School Nursing Practice. The purpose of the standards of school nursing practice is to fulfill the profession’s obligation to provide a means of providing safe, consistent, quality care. The current school nursing standards have evolved over a 20-year period from numerous documents published by the American Nurses Association (ANA), the NASN, and the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education and are available on this book’s website as Website Resource 30A.

![]()

Roles of the School Nurse

The NASN recently outlined and defined roles of the school nurse (NASN, 2011a). These roles include the following:

• Facilitation of normal development and positive student response to interventions

• Leadership in promoting health and safety, including a healthy environment

• Provision of quality health care and intervention with actual and potential health problems

• Use of clinical judgment in proving case management services