Schizophrenia and Schizophrenic-like Disorders

The burden of psychiatric conditions has been heavily underestimated. Disability caused by active psychosis in schizophrenia produces disability equal to quadriplegia.

Learning objectives

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Compare at least three current theories contributing to the understanding of the development of schizophrenia.

Articulate the classification of the five phases of schizophrenia.

Interpret Bleuler’s 4 A’s.

Differentiate the positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms of schizophrenia.

Distinguish the five subtypes of schizophrenia.

Analyze why an antidepressant drug and an atypical antipsychotic agent may be necessary to stabilize the clinical symptoms of schizophrenia.

Articulate the criteria that indicate the presence of metabolic syndrome.

Compare and contrast the rationale for the use of the following interactive therapies generally effective when providing care for clients with schizophrenia: group therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and personal therapy.

Discuss the purpose of including the client and family in multidisciplinary treatment team meetings.

Comprehend the importance of continuum of care for clients with schizophrenia.

Construct therapeutic nursing interventions when planning care for a client with the diagnosis of schizophrenia, paranoid type.

Key Terms

Affective disturbance

Ambivalence

Autistic thinking

Awakening phenomena

Awareness syndrome

Dementia praecox

Disorganized symptoms

Dopamine hypothesis

Double-bind situation

Echolalia

Echopraxia

Looseness of association

Metabolic syndrome

Negative symptoms

Pica

Positive symptoms

Psychogenic polydipsia

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is considered the most common and disabling of the psychotic disorders. Although it is a psychiatric disorder, it stems from a physiologic malfunctioning of the brain. This disorder affects all races, and is more prevalent in men than in women. No cultural group is immune, and persons with intelligence quotients of the genius level are not spared. Schizophrenia occurs twice as often in people who are unmarried or divorced as in those who are married or widowed. People with schizophrenia are more likely to be members of lower socioeconomic groups.

The onset of schizophrenia may occur late in adolescence or early in adulthood, usually before the age of 30. Although the disorder has been diagnosed in children, approximately 75% of persons diagnosed as having schizophrenia develop the clinical symptoms between the ages of 16 and 25 years. Schizophrenia usually first appears earlier in men, in their late teens or early twenties, than in women, who are generally affected in their twenties or early thirties.

Clinical symptoms can be draining on both the person with schizophrenia and his or her family because it is considered a chronic syndrome that typically follows a deteriorating course over time. Clients experience difficulty functioning in society, in school, and at work. Family members often provide the financial support, possibly assuming the responsibility for monitoring medication compliance.

Approximately 2.2 million people, or 1% of the earth’s population, suffer from schizophrenia or schizophrenic-like disorders (disorders similar to schizophrenia). Schizophrenia impairs self-awareness for many individuals so that they do not realize they are ill and in need of treatment. Statistics indicate that approximately 40% of these individuals (or 1.8 million people) do not receive psychiatric treatment on any given day, resulting in homelessness, incarceration, or violence (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001).

Deinstitutionalization and cost shifting by state and local governments to the federal government, namely Medicaid, have contributed greatly to this crisis situation. Additionally, changes in state laws (advocated by civil liberties groups) have made it very difficult to assist in the treatment of psychotic individuals unless they pose an imminent danger to themselves or others. Consequently, individuals with psychotic disorders have been relocated into nursing homes, general hospitals, or prisons, or have been forced to live in the streets or homeless shelters (see Chapter 35).

Schizophrenia has been linked to violence. Predictors of violence among persons with psychotic disorders include failure to take medication, drug or alcohol abuse, delusional thoughts, command hallucinations, or a history of violence. Approximately 50% of schizophrenic clients have a substance-abuse disorder (Sullivan, 2004).

In response to this crisis situation and because of the heterogeneity and complexities of this illness, the National Institute of Mental Health has given the highest priority to training, research, and education about schizophrenia and schizophrenic-like disorders. For example, phase I results of the three-phase Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) in schizophrenia have recently been released. The 18-month study included nearly 1,500 subjects. During the study, researchers compared the efficacy of the newer atypical antipsychotics olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and ziprasidone (Geodon) with each other and with a typical first-generation antipsychotic, perphenazine (Trilafon). The purpose of the study is to determine which medications are most effective and, as a result, improve the quality of life for people with schizophrenia. A disappointingly high discontinuation rate (74% of the subjects) occurred within a few months of the study. In addition, 42% of the subjects met the criteria for metabolic syndrome (diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or hypertension), placing them at risk to die of cardiovascular causes within 10 years. The results of phase II findings, which have not yet been released, will focus on clients who did not improve with phase I regimens because of efficacy or tolerability problems and were switched to other antipsychotic therapies (Hillard, 2006; Nasrallah, 2006). Given the information released during the CATIE study, one can see that the role of the nurse can be quite challenging as client and family education is provided to promote health maintenance, lifestyle modifications, and client empowerment.

This chapter discusses the history, etiology, clinical symptoms, and diagnostic characteristics associated with schizophrenia and schizophrenic-like disorders. The different classifications of schizophrenia are

presented, and the role of the psychiatric–mental health nurse is described, emphasizing the importance of medication management.

presented, and the role of the psychiatric–mental health nurse is described, emphasizing the importance of medication management.

History of Schizophrenia

Written descriptions of schizophrenia have been traced back to Egypt during the year 200 BC. At that time, mental and physical illnesses were regarded as symptoms of the heart and the uterus and thought to originate from blood vessels, fecal matter, a poison, or demons. Ancient Greek and Roman literature indicated that the general population had an awareness of schizophrenia. Greek physicians blamed delusions and paranoia on an imbalance of bodily humors. Hippocrates believed that insanity was caused by a morbid state of the liver. By the 18th century, an understanding about the relationship between nerves and organs increased, and it was finally decided that disorders of the central nervous system were the cause of insanity.

Although the term schizophrenia (from the Greek roots schizo [split] and phrene [mind]) is less than 100 years old, it was first described as a specific mental illness in 1887 by a psychiatrist, Emil Kraepelin. Eugene Bleuler, a Swiss psychiatrist, coined the term in 1911. He was also the first individual to describe the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Both Kraepelin and Bleuler subdivided schizophrenia into three categories based on prominent symptoms and prognoses: disorganized, catatonic, and paranoid. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) lists five classifications originally described by DSM-III in 1980: disorganized, catatonic, paranoid, residual, and undifferentiated.

The 19th century saw an explosion of information about the body and mind. Evidence was mounting that mental illness was caused by disease in the brain. As a result of research during the last two decades, the evidence that schizophrenia is biologically based has accumulated rapidly. Furthermore, research in the genetics of human disease is also helping to develop more effective therapies and eventually cures for this potentially disabling mental disorder (Schizophrenia.com, 2006).

Etiology of Schizophrenia

Recent research suggests that schizophrenia involves problems with brain chemistry and brain structure. However, no single cause has been identified to account for all cases of schizophrenia. Scientists are currently investigating possible factors contributing to the development of schizophrenia. Examples of possible factors include genetic predisposition; biochemical and neurostructural changes in the brain; organic or pathophysiologic changes of the brain; environmental or cultural influences; perinatal influences; and psychological stress. Research is rapidly progressing beyond the level of simple transmitters to define neuroanatomical and neurophysiological circuits that lie at the heart of cerebral dysfunction in schizophrenia. Furthermore, brain-imaging technology has demonstrated that schizophrenia is as much an organic brain disorder as is Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis (Brier, 1999; Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Sherman, 1999a; Spollen, 2005). Numerous theories about the cause of schizophrenia have been developed. Some of the more common theories are described here.

Genetic Predisposition Theory

The genetic, or hereditary, predisposition theory suggests that the risk of inheriting schizophrenia is 10% to 20% in those who have one immediate family member with the disease, and approximately 40% if the disease affects both parents or an identical twin. Researchers have recently identified three patient groups considered to be at “ultra-high risk” for the development of schizophrenia. The risk factors for one group include a family history of psychosis, schizotypal personality disorder (see Chapter 24), and the presence of functional decline for at least 1 month and not longer than 5 years. The conversion rate for this group is considered to be 40% to 60%. Approximately 60% of people with schizophrenia have no close relatives with the illness (Narasimhan & Buckley, 2005; Sherman, 1999a).

The first true etiologic subtype of schizophrenia, the consequence of a chromosome deletion referred to as the 22q1 deletion syndrome, has been identified. Persons with this syndrome have a distinct facial appearance, abnormalities of the palate, heart defects, and immunologic deficits. The risk of developing schizophrenia in the presence of this syndrome appears to be approximately 25%, according to Dr. A. Bassett of the University of Toronto (Baker, 1999; Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Sherman, 1999d).

Scientists also may be close to identifying genetic locations of schizophrenia, believed to be on human chromosomes 13 and 8. One study found that mothers

of clients with schizophrenia had a high incidence of the gene type H6A-B44 (Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Sherman, 1999d).

of clients with schizophrenia had a high incidence of the gene type H6A-B44 (Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Sherman, 1999d).

Research is now exploring how to proceed with genome scanning and DNA marker technology. To date, seven genes have been confirmed by at least several groups of investigators worldwide as increasing the risk for schizophrenia. Over the next 2 to 3 years, it is likely that between 10 and 20 genes will be implicated (Weinberger, 2004). The reader is referred to resources in the field of neuropsychiatric medicine for additional information.

Biochemical and Neurostructural Theory

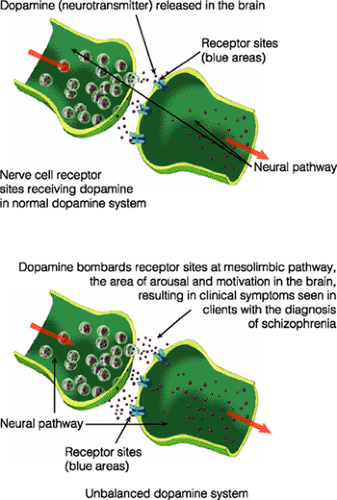

The biochemical and neurostructural theory includes the dopamine hypothesis: that is, that an excessive amount of the neurotransmitter dopamine allows nerve impulses to bombard the mesolimbic pathway, the part of the brain normally involved in arousal and motivation. Normal cell communication is disrupted, resulting in the development of hallucinations and delusions, symptoms of schizophrenia (Fig. 22-1).

The cause of the release of high levels of dopamine has not yet been found, but the administration of neuroleptic medication supposedly blocks the excessive release. Other neurotransmitters or chemicals in the brain, such as the amino acids glycine and glutamate, and proteins called SNAP-25 and a-fodrin, are also being studied. For example, glutamate is considered to be the most prevalent excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. Dysfunction of glutamate receptors, which are likely present on every cell in the brain, may be the cause of many neurologic and psychiatric disorders (Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Spollen, 2005).

Abnormalities of neurocircuitry or signals from neurons are being researched as well. Supposedly, a neuronal circuit filters information entering the brain and sends the relevant information to other parts of the brain for determining action. A defective circuit can result in the bombardment of unfiltered information, possibly causing both negative and positive symptoms. Overwhelmed, the mind makes errors in perception and hallucinates, draws incorrect conclusions, and becomes delusional. To compensate for this barrage, the mind withdraws and negative symptoms develop (Kennedy, Pato, Bauer, et al., 1999; Well-Connected, 1999). Cognitive deficits, impairments of attention and executive function, and certain types of memory deficits may be the result of abnormal circuitry in the prefrontal cortex (Moore, 2005).

Organic or Pathophysiologic Theory

Those who suggest the organic or pathophysiologic theory offer hope that schizophrenia is a functional deficit occurring in the brain, caused by stressors such as viral infection, toxins, trauma, or abnormal substances. They also propose that schizophrenia may be a metabolic disorder. Extensive research needs to be done, because the case for this theory rests mainly on circumstantial evidence (Well-Connected, 1999).

Environmental or Cultural Theory

Proponents of the environmental or cultural theory state that the person who develops schizophrenia has

a faulty reaction to the environment, being unable to respond selectively to numerous social stimuli. Theorists also believe that persons who come from low socioeconomic areas or single-parent homes in deprived areas are not exposed to situations in which they can achieve or become successful in life. Thus they are at risk for developing schizophrenia. Statistics are likely to reflect the alienating effects of this disease rather than any causal relationship or risk factor associated with poverty or lifestyle (Kolb, 1982).

a faulty reaction to the environment, being unable to respond selectively to numerous social stimuli. Theorists also believe that persons who come from low socioeconomic areas or single-parent homes in deprived areas are not exposed to situations in which they can achieve or become successful in life. Thus they are at risk for developing schizophrenia. Statistics are likely to reflect the alienating effects of this disease rather than any causal relationship or risk factor associated with poverty or lifestyle (Kolb, 1982).

Perinatal Theory

Experts suggest that the risk of schizophrenia exists if the developing fetus or newborn is deprived of oxygen during pregnancy or if the mother suffers from malnutrition or starvation during the first trimester of pregnancy. The development of schizophrenia may occur during fetal life at critical points in brain development, generally the 34th or 35th week of gestation. The incidence of trauma and injury during the second trimester and birth has also been considered in the development of schizophrenia (Well-Connected, 1999).

Psychological or Experiential Theory

Although genetic and neurologic factors are believed to play major roles in the development of schizophrenia, researchers also have found that the prefrontal lobes of the brain are extremely responsive to stress. Individuals with schizophrenia experience stress when family members and acquaintances respond negatively to the individual’s emotional needs. These negative responses by family members can intensify the individual’s already vulnerable neurologic state, possibly triggering and exacerbating existing symptoms.

Stressors that have been thought to contribute to the onset of schizophrenia include poor mother–child relationships, deeply disturbed family interpersonal relationships, impaired sexual identity and body image, rigid concept of reality, and repeated exposure to double-bind situations (Kolb, 1982). A double-bind situation is a no-win experience, one in which there is no correct choice. For example, a parent tells a child who is wearing new white tennis shoes that he may go out to play in the park when it stops raining but that he is not to get his shoes dirty. At the same time, the parent’s body language and facial expression convey the message that the parent prefers that the child stay indoors. The child does not know which message to follow.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics

Symptoms of schizophrenia may appear suddenly or develop gradually over time. It is a disorder that currently is not curable. Five phases of schizophrenia have been identified. They include the premorbid, prodromal (ie, beginning), onset, progressive, and chronic or residual phases. No clinical symptoms of schizophrenia are expressed during the premorbid phase. Gradual, subtle behavioral changes appear during the prodromal phase. For example, tension, the inability to concentrate, insomnia, withdrawal, or cognitive deficits may be present. These changes worsen and become recognizable as the symptoms that characterize schizophrenia. Cognitive deficits have been proven to exist 20 years before the third phase, referred to as the onset phase of schizophrenia, occurs. Once the symptoms of schizophrenia manifest, the illness evolves into the progressive phase. During this phase, clients may recover from the first episode and experience repeated relapses. The end stage of schizophrenia is referred to as the chronic or residual phase, during which time the client has experienced repeated episodes and relapses for a number of years (Lieberman, 2004; Moon, 1999).

In 1896, Emil Kraepelin introduced the term dementia praecox, a syndrome characterized by hallucinations and delusions. As noted earlier, Eugene Bleuler introduced the term schizophrenia and cited symptoms referred to as Bleuler’s 4 A’s: affective disturbance, autistic thinking, ambivalence, and looseness of association. Affective disturbance refers to the person’s inability to show appropriate emotional responses. Autistic thinking is a thought process in which the individual is unable to relate to others or to the environment. Ambivalence refers to contradictory or opposing emotions, attitudes, ideas, or desires for the same person, thing, or situation. Looseness of association is the inability to think logically. Ideas expressed have little, if any, connection and shift from one subject to another.

Clinical symptoms fall into three broad categories: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and disorganized symptoms. Positive symptoms reflect the presence of overt psychotic or distorted behavior, such as hallucinations, delusions, or suspiciousness, possibly caused by an increased amount of dopamine affecting the cortical areas of the brain. Negative symptoms reflect a diminution or loss of normal functions, such as affect, motivation, or the ability to enjoy activities;

these symptoms are thought to result from cerebral atrophy, an inadequate amount of dopamine, or other organic functional changes in the brain. The category of disorganized symptoms was recently added. This category refers to the presence of confused thinking, incoherent or disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior such as the repetition of rhythmic gestures. These symptoms and diagnostic characteristics are listed in the accompanying Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics box.

these symptoms are thought to result from cerebral atrophy, an inadequate amount of dopamine, or other organic functional changes in the brain. The category of disorganized symptoms was recently added. This category refers to the presence of confused thinking, incoherent or disorganized speech, and disorganized behavior such as the repetition of rhythmic gestures. These symptoms and diagnostic characteristics are listed in the accompanying Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics box.

Clinical Symptoms and Diagnostic Characteristics/Schizophrenia

Clinical Symptoms

Positive Symptoms

Excess or distortion of normal functions

Delusions (persecutory or grandiose)

Conceptual disorganization

Hallucinations (visual, auditory, or other sensory mode)

Excitement or agitation

Hostility or aggressive behavior

Suspiciousness, ideas of reference

Pressurized speech

Bizarre dress or behavior

Possible suicidal tendencies

Negative Symptoms

Diminution or loss of normal functions

Anergia (lack of energy)

Anhedonia (loss of pleasure or interest)

Emotional withdrawal

Poor eye contact (avoidant)

Blunted affect or affective flattening

Avolition (passive, apathetic, social withdrawal)

Difficulty in abstract thinking

Alogia (lack of spontaneity and flow of conversation)

Dysfunctional relationship with others

Disorganized Symptoms

Cognitive defects/confusion

Incoherent speech

Disorganized speech

Repetitive rhythmic gestures (such as walking in circles or pacing)

Attention deficits

Diagnostic Characteristics

Evidence of two or more of the following:

Delusions

Hallucinations

Disorganized speech

Grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

Negative symptoms

Above symptoms present for a major portion of the time during a 1-month period

Significant impairment in work or interpersonal relations, or self-care below the level of previous function

Demonstration of problems continuously for at least a 6-month interval

Symptoms unrelated to schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic symptoms and not the result of a substance-related disorder or medical condition

Two diagnostic categories have been developed to describe the etiology and onset of schizophrenia: type I and type II. In type I schizophrenia, the onset of positive symptoms is generally acute. Type I symptoms generally respond to typical neuroleptic medication. Theorists believe that an increased number of dopamine receptors in the brain, normal brain structure, and the absence of intellectual deficits contribute to a better prognosis than for those identified with type II schizophrenia.

Type II schizophrenia is characterized by a slow onset of negative symptoms caused by viral infections and abnormalities in cholecystokinin. Intellectual decay occurs. Enlarged ventricles are present. Response to typical neuroleptic medication is minimal. However, negative symptoms generally respond to atypical antipsychotic medication (Sherman, 1999c).

As noted earlier, the DSM-IV-TR identifies five subtypes of schizophrenia: paranoid, catatonic, disorganized, undifferentiated, and residual (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). A brief summary of each subtype and a clinical example of each of the first three subtypes are given in the following paragraphs. Box 22-1 summarizes the five subtypes of schizophrenia.

Paranoid Type

Clients exhibiting paranoid schizophrenia tend to experience persecutory or grandiose delusions and

auditory hallucinations (Fig. 22-2). They also may exhibit behavioral changes such as anger, hostility, or violent behavior. Clinical symptoms may pose a threat to the safety of self or others. (See Clinical Example 22-1: The Client With Schizophrenia, Paranoid Type.) Prognosis is more favorable for this subtype of schizophrenia than for the other subtypes of schizophrenia. Clients in whom schizophrenia occurs in their late twenties and thirties usually have established a social life that may help them through their illness. In addition, ego resources of paranoid clients are greater than those of clients with catatonic and disorganized schizophrenia (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

auditory hallucinations (Fig. 22-2). They also may exhibit behavioral changes such as anger, hostility, or violent behavior. Clinical symptoms may pose a threat to the safety of self or others. (See Clinical Example 22-1: The Client With Schizophrenia, Paranoid Type.) Prognosis is more favorable for this subtype of schizophrenia than for the other subtypes of schizophrenia. Clients in whom schizophrenia occurs in their late twenties and thirties usually have established a social life that may help them through their illness. In addition, ego resources of paranoid clients are greater than those of clients with catatonic and disorganized schizophrenia (Sadock & Sadock, 2003).

Box 22.1: Classification of Subtypes of Schizophrenia

Paranoid

Preoccupation with one or more delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations

None of the following is prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect

Catatonic

At least two of the following are present:

Motor immobility (ie. rigidity), waxy flexibility, or stupor

Excessive motor activity that is purposeless

Extreme negativism or mutism

Peculiarities of voluntary movement as evidenced by posturing, stereotyped movements, prominent mannerisms or prominent grimacing

Echolalia (repeats all words or phrases heard) or echopraxia (mimics actions of others)

Disorganized

All of the following are prominent and criteria are not met for catatonic type:

Disorganized speech

Disorganized behavior

Flat or inappropriate affect

Undifferentiated

Meets diagnostic characteristics but not the criteria for paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic subtypes

Residual

Absence of prominent delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior

Continuing evidence of, in attenuated form, the presence of negative symptoms or two or more symptoms of diagnostic characteristics

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access