1. Define, spell, and pronounce the terms listed in the vocabulary. 2. Describe scheduling guidelines. 3. Discuss the advantages of computerized appointment scheduling. 4. Explain the features that should be considered when choosing an appointment book. 5. Explain how self-scheduling can reduce the number of calls to the medical office. 6. Discuss pros and cons of various types of appointment management systems. 7. Explain the importance of legible writing in the appointment book. 8. Explain the basic procedure to follow when the office is behind schedule. 9. Discuss the benefits of offering choices to patients when scheduling appointments. 10. Identify critical information required for scheduling patient admissions and/or procedures. 11. Discuss several methods of dealing with patients who consistently arrive late. 12. Name several reasons for failed appointments. 13. Recognize office policies and protocols for handling appointments. established patients Patients who are returning to the office who have previously been seen by the physician. integral (in′-ti-grul) Essential; being an indispensable part of a whole. interaction A two-way communication; mutual or reciprocal action or influence. intermittent Coming and going at intervals; not continuous. interval Space of time between events. no-show A person who fails to keep an appointment without giving advance notice. precertification A process required by some insurance carriers in which the provider must prove medical necessity before performing a procedure. prerequisite (pre-re′-kwe-zut) Something that is necessary to an end or to carry out a function. proficiency (pruh-fi′-shun-se) Competency as a result of training or practice. reimbursement Payment of benefits to the physician for services rendered according to the guidelines of the third-party payer. socioeconomic Relating to a combination of social and economic factors. Ramona West is the medical assistant in charge of scheduling appointments for Dr. Charlotte Brown. Ramona is an extremely organized person who thinks quickly and creatively. One of her professional goals is to ensure that the office remains on schedule throughout the day and that patient’s waiting time is kept to an absolute minimum. She is fortunate that Dr. Brown is cooperative and time oriented, and they work well together to reach this common goal. Ramona usually arrives at work at least 15 minutes early to begin her preparations for the day. She reviews the electronic medical record for each patient to make sure test results from previous visits are available to the physician and that the medical record is complete. She pays special attention to the patients who arrive in the office as she completes her daily tasks, remembering the importance of providing patients with good customer service. Ramona greets each patient by name and carries on a brief but cordial conversation. Patients appreciate that she goes the extra mile to remember something about them, and this promotes excellent patient relations. Ramona leaves a little time in the morning and afternoon for emergency appointments. The office uses an automatic call routing system to contact patients and confirm appointments in advance, which increases her show rate. Her friendly, caring attitude makes her a favorite among the patients, and Dr. Brown is pleased with the relationship-building skills Ramona has developed. While studying this chapter, think about the following questions: • How can the medical assistant contribute to an efficient daily routine? • How does the medical assistant contribute to keeping the daily schedule on track? • How can the schedule be put back on track when emergencies disrupt the day? • How does the flexibility of the medical assistant contribute to office efficiency? The physician’s time is the most valuable asset of a medical practice. The person responsible for scheduling this time must understand the practice, be familiar with the working habits and preferences of the physician (or physicians), and have clear guidelines for time management in the practice. Appointment scheduling is the process that determines which patients the physician sees, the dates and times of appointments, and how much time is allotted to each patient based on the complaint and the physician’s availability. Time management involves the realization that unforeseen interruptions and delays always occur. Most medical care providers find that efficient appointment scheduling is one of the most important factors in the success of the practice. Scheduling can be done in a number of ways, and each facility must find the way that suits it best. Patients often complain that the amount of money they pay to see the physician does not correspond with the amount of time the physician spends with the patient. A patient may say, “I only saw the doctor for 5 minutes and could not even remember all the questions I wanted to ask!” The patient must feel confident that the physician will take enough time to understand his or her concerns. Well-planned scheduling and adherence to that schedule allow the physician to do more than run in and out of examination rooms with little time for the patient to talk with the physician. The person scheduling appointments must learn the physician’s habits and desires. If the physician suggests scheduling patients every 15 minutes but always spends 20 to 25 minutes with a patient, the schedule must be adjusted. Talk with the physician and/or office manager and compromise so that the schedule is workable. Some physicians need prompting to end the patient visit and move to the next patient. The medical assistant assisting in the examination room can help the physician remain on schedule, because he or she teams with the scheduler and they work together for an efficient flow of patients through the office. The scheduling system must be individualized to the specific practice. The following general guidelines can be applied to any practice, whether computer or paper based. Four factors must be considered in scheduling: the patient’s needs, the physician’s preferences and habits, the facilities available, and the duration of office visits. Consider the socioeconomic status of the area being served when determining office hours and appointment times. The office staff should answer the following questions: • Is the office in a busy metropolitan area or a rural agricultural community? • Are the patients young, middle aged, or retirement age? • Is the area more industrial or residential? • Are evening and weekend appointments essential for most of the patients served? After these elements have been considered, the scheduler must allot time based on the patient’s needs for each individual office visit. These needs can be assessed by determining the following: • What is the purpose of this visit? • Is the patient a parent who prefers to schedule appointments while the children are at school? • Does the patient object to traveling after dark? • Is the patient a day worker who cannot take time off from a job? • Is the patient a child whose parents both work during the day? The office should make every attempt to meet the patient’s needs while balancing the physician’s preferences and the available facilities. Consider the preferences and habits of the physicians in the practice before establishing and implementing a scheduling plan. Ask the following questions: • Does the physician become restless if the reception room is not packed with waiting patients? • Does the physician worry if even one patient is kept waiting? • Is the physician habitually late? • Does the physician move easily from one patient to another? • Does the physician require a “break time” after a few patients? All of these preferences and habits become an integral part of the scheduling process (Figure 10-1). Keep in mind that the physician cannot spend every moment of the day with patients. The physician also has telephone calls to make and receive, reports to examine and dictate, meetings to attend, mail to answer, and many other business responsibilities. An experienced staff can handle many but not all of these tasks. Getting a patient into the office at a time when no facilities are available for the services needed is pointless. For example, suppose that an office with two physicians has only one room that can be used for minor surgery. Do not schedule two patients requiring minor surgery for the same time block, even if both doctors could be available. If the office has only one electrocardiograph, do not book two electrocardiographic procedures at the same time. As the medical assistant gains proficiency in scheduling, it becomes easier to pair patient needs with the available facilities according to the physician’s preference. Major equipment frequently used or a certain room with such equipment may need its own scheduling column in the appointment book or software system. The medical assistant who performs scheduling duties must know the amount of time required for various office visits and procedures. The office policy and procedure manual should have a list of the procedures performed in the physician’s office with a notation of the time required for the procedure using established priorities. The time blocks are important, because the physician’s reimbursement from insurance companies is based partly on the time requirements of the procedure or office visit. When scheduling, make sure to allow enough time to complete a procedure; for example, never schedule a Pap smear or minor surgery in a 10- or 15-minute time slot. The two most common methods of appointment scheduling are computerized scheduling and appointment book scheduling. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and the physician’s office should weigh the benefits and choose the method that best suits the physician and the staff. The computer has replaced the appointment book in many practices. Software for appointment scheduling ranges from relatively simple programs that merely display available and scheduled times to more sophisticated systems that perform several other functions. Many programs can display such information as the length and type of appointment required and day or time preferences. The computer then can select the best appointment time based on the information entered into the computer. The computer also can be used to keep track of future appointments. For example, when a patient calls and inquires about an appointment, the system can search by his or her name to find the time and date. Printouts also can be run to show the physician’s daily schedule, including the patients’ names and telephone numbers and the reason for the visit. Multiple copies of these schedules can be made, according to the needs of the practice. Computer scheduling allows more than one person to access the system at once, and the information is available to all operators. The medical assistant can generate a hard copy of the next day’s appointments before leaving each evening. In some facilities, employees keep an appointment book as a backup to computer scheduling. Office suppliers carry a variety of appointment book styles. Some appointment books show an entire week at a glance, and many are color coded, with a special color used for each day of the week (Figure 10-2). This is very helpful when the physician asks the patient to return, for instance, in 2 weeks. If Wednesdays are colored yellow, the medical assistant can flip quickly to the correct day 2 weeks later and schedule the appointment. Multiple columns may be available to correspond with the number of doctors in a group practice, and the time can be divided according to their preferences. The future of appointment scheduling includes self-scheduling, which is a method by which a patient can log on to the Internet and view a facility’s schedule, then select his or her own appointment time and make the appointment right then. The system should allow for patient confidentiality by showing only available times. Other patients’ names should never be visible on an online system. Software is available that allows the patient to self-schedule through secure links to the physician’s appointment book. The software or Internet site for the physician’s office should give the patient guidelines as to the amount of time needed for certain appointments or should allow only a certain length of time to be self-scheduled, such as 15 minutes. These systems will reduce the number of calls to the office and are available to the patient 24 hours a day. Some of these systems also send an automatic e-mail reminder to the patient the day before the appointment, requesting a reply to confirm. These systems are less frustrating to patients, who do not have to wait on hold to speak to the person who does scheduling for the office. Lengthy or complicated appointments should be scheduled through the office staff. Although this type of system for making appointments appeals to most technologically savvy people, some patients stringently reject online scheduling because it requires at least minimal computer skills, which the patient may not have or be comfortable performing. If this method is used, some allowance must be made for patients who do not have computers. Other patients may object to online scheduling because they do not want their name anywhere on the Internet. This is a valid issue, and the office should allow these patients to schedule over the phone. After an appropriate method of setting appointments has been chosen, some advance preparation should be done. This is sometimes called establishing the matrix (Procedure 10-1). Block out time slots when the physician routinely is not available to see patients, such as days off, holidays, lunch or dinner breaks, time for hospital rounds, and meetings. In the space where a patient’s name normally would appear, note the reason the time is blocked off. Most electronic scheduling software allows the user to create a template that can be used repeatedly when new appointment pages are needed. The template can be set to block time slots unavailable for appointments automatically, such as lunch hours and regular meeting times. Always try to account for every time period in each day. Because the appointment book can be used as a legal record, it must be accurate and maintained so that it provides correct information about the patients at the office. Patients are expected to follow the physician’s orders; this includes keeping appointments. If a patient does not show up for an appointment or cancels it and does not reschedule, a notation of this fact should be placed in the patient’s medical record. If a patient reschedules an appointment and subsequently keeps it, there is no need to document that it was rescheduled. Pencil is used in the appointment book so that making changes is easier. The information in the book includes the patient’s name and a phone number where the patient can be reached. Some offices list the reason for the appointment, but most note only the name and phone number. The reason for the visit is not necessary if the medical assistant references the time needed for the appointment and blocks off that amount of time. Although the appointment book can be used as a legal record, actual medical records are more likely to be used in matters of litigation. Because progress notes are dated, a copy of the medical record shows all pertinent information about the patient’s adherence to the physician’s orders, including the appointments with the physician. Pens are permanent, but the book can become illegible if a number of patients change or cancel their appointments. Because the appointment book could be produced in litigation as a legal record, it should be kept for the number of years that constitute the statute of limitations in that individual state. If the appointment book is discarded, its contents should be shredded to protect patient privacy. Different types of appointment scheduling are used to meet the various needs of the medical facility, the providers, and the patients. Some offices use a combination of methods to create the right mix of activity during the day and to ensure that the day runs smoothly and efficiently. The medical assistant should become proficient at managing appointments (Procedure 10-2). The following section presents several methods of appointment scheduling. With the open office hours method, the facility is open at given hours of the day or evening, and the patients are “scheduled” by the physician, who mentions to the patient that he or she should return “in a couple of weeks” for follow-up. The patients come in at intermittent times, knowing they will be seen in the order of their arrival. Physicians who use this method say that it eliminates the annoyance of broken appointments and an office running behind schedule. The open office hours method also has been called tidal wave scheduling. Some of these facilities allow online or telephone check-in, and patients are notified when it is close to their turn with the provider. Few healthcare facilities in metropolitan areas have open office hours with no scheduled appointments, but this system still is found in some rural areas, where the way of life is governed not so much by the clock as by the needs of the people in the area. Open office hours scheduling is most commonly used at laboratories, imaging facilities, urgent care clinics, and emergency departments. Many emergency departments are open 24 hours a day. Although called emergency departments, many of these facilities deal with general practice cases. The open office hours system can have many disadvantages. The office may already be crowded when the physician arrives, resulting in an extremely long wait for some patients. Patients may arrive in waves throughout the day, which causes parts of the day to be very busy and parts to be slow. This makes getting other office duties accomplished difficult. Without planning, the facilities and staff can be overburdened. Studies have shown that practitioners can see more patients with less pressure when their appointments are scheduled. Unfortunately, the skill required for scheduling appointments often is not fully appreciated by the practitioner or office manager, and the responsibility is delegated to the least-qualified medical assistant. An efficient, bright individual proficient at multitasking should be assigned to the scheduling of duties. Although the skill and attitude of the assistant who manages the appointment schedule are very important, the ultimate success of the system lies in the cooperation of the physicians. Different procedures require different amounts of time; the scheduler must understand how long it takes to draw blood, fill out new patient paperwork, and weigh and check the patient in; all procedures, even the simplest, must have an associated amount of time needed to complete the task. If the patient needs an average of 15 minutes to do new patient paperwork, this time must be included in the schedule. (This is why many offices ask new patients to arrive 15 minutes early for their appointment.) If an allergy shot takes only 20 minutes from check-in to checkout and does not require the patient to see the physician, the scheduler knows that other patients can see the physician while the medical assistant gives the allergy shot. The scheduler cannot efficiently set appointments without developing the skill of accurately assessing how long an office procedure takes. Most scheduling practices are carryovers from the days when expectant mothers of families with young children relied on one wage earner. Today families commonly have two working parents. As a result, many healthcare providers are turning to extended day and flexible office hours. Staff hours are affected by these schedules, but this flexibility works to the advantage of the patient and the staff at the physician’s office. Patients appreciate flexible office hours, because they can schedule an appointment after work or after children’s school hours. Evening and weekend hours may increase the size of the practice because of the convenience offered to patients. Wave scheduling is an attempt to create short-term flexibility within each hour. Wave scheduling assumes that the actual time needed for all the patients seen will average out over the course of the day. Instead of scheduling patients at each 20-minute interval, wave scheduling places three patients in the office at the same time, and they are seen in the order of their arrival. This way, one person’s late arrival does not disrupt the entire schedule. The wave schedule can be modified in several ways. For example, one method is to have two patients scheduled to come in at 10 AM and a third at 10:30 AM. This hourly cycle is repeated throughout the day. In another version, patients are scheduled to arrive at given intervals during the first half of the hour, and none are scheduled to arrive during the second half of the hour. Booking two patients to come in at the same time, both of whom are to be seen by the physician, is poor practice. Of course, if each appointment is expected to take only 5 minutes, no harm is done by telling both to come at the same time and reserving a 15-minute period for the two. This is simply one method of wave scheduling. However, if each patient requires 15 minutes, two require 30 minutes. This must be reflected in the scheduling. It is not considered double-booking if a patient comes to the office to receive a treatment by someone other than the physician, such as a patient receiving physical therapy or an antiallergy injection. Grouping or categorizing of procedures is another method of scheduling that appeals to many practitioners. For instance, an internist might reserve all morning appointments for complete physical examinations, or a pediatrician might keep that time for well-baby visits. A surgeon might devote one day each week to seeing only referral patients. Obstetricians often schedule pregnant patients on different days from gynecology patients. The physician and staff can experiment with different groupings until the plan that works best for the practice eventually becomes evident. In applying a grouping system of appointments, the medical assistant may find it helpful to color-code the sections of the appointment book reserved for designated procedures. Often appointments are made months in advance. When any appointment is made, an appointment card should be completed and given to the patient. All appointment cards should mention that patients must give 24 hours’ notice if they are unable to keep the time reserved for them. Most offices have some type of confirmation procedure by which patients are called the day before to verify that they intend to keep the appointment. When booking appointments, a medical assistant should make it a policy to leave some open time during each day’s schedule so that if a patient calls with a special problem that is not an immediate emergency, time will be available to book the patient for at least a brief visit. Mondays and Fridays generally are the most hectic days of the week. Keeping one time slot available in the morning and the afternoon specifically for emergencies also is a wise practice. A busy physician always fills these open slots, and having them in the schedule causes the least disruption during the day. If possible, set aside time in the morning and afternoon for a break. Even 15 minutes can give the physician time to return calls from patients, verify prescription calls, or answer questions. Be aware of the amount of time the patient sits in the reception area. Ideally, the patient’s name is called to go to the examination room precisely at the scheduled appointment time (Figure 10-3). However, the scheduling process has failed if the patient then waits in the back office for 30 minutes to see the physician. Make it clear to the patient whether he or she is free to leave the office after the physician has finished the examination. Some patients mistakenly wait in the examination room until told they are free to leave. Always make sure the patient knows when to go where.

Scheduling Appointments

Learning Objectives

Vocabulary

Scenario

Using Established Priorities for Appointment Scheduling

Patient Needs

Physician Preferences and Habits

Available Facilities

Duration of Office Visits

Methods of Scheduling Appointments

Computer Scheduling

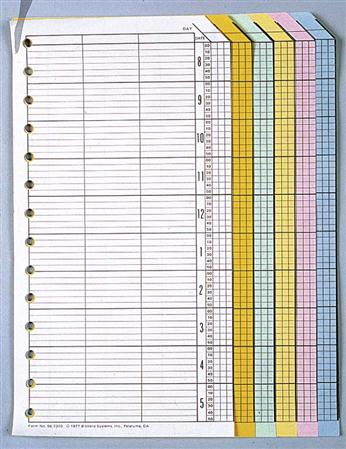

Appointment Book Scheduling

Self-Scheduling

Advance Preparation

Legality of the Appointment Book

Types of Appointment Scheduling

Open Office Hours

Scheduled Appointments

Flexible Office Hours

Wave Scheduling

Modified Wave Scheduling

Double-Booking

Grouping Procedures

Advance Booking

Time Patterns

Patient Wait Time

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree