Safety and Quality in Pharmacotherapy

Objectives

• Discuss the QSEN initiative related to safe administration of medications.

• Describe the “five-plus-five” rights of medication administration.

• Analyze safety risks for medication administration.

• Discuss safe disposal of medications.

• Discuss high-alert drugs and strategies for safe administration.

• Describe application of safe practices when ordering medications on the Internet.

• Discuss safety bases of pregnancy categories.

• Apply the nursing process to safe administration of medications.

Key Terms

absorption, p. 130

distribution, p. 130

informed consent, p. 124

medication reconciliation, p. 126

pharmacogenetics, p. 130

right assessment, p. 123

right patient, p. 121

right documentation, p. 123

right dose, p. 122

right drug, p. 121

right evaluation, p. 124

right route, p. 123

right time, p. 122

right to education, p. 123

right to refuse, p. 124

stock drug method, p. 122

tolerance, p. 123

toxicity, p. 130

unit dose method, p. 122

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/KeeHayes/pharmacology/

Nearly 4 billion prescriptions were written in the United States in 2010, according to the IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Prescription medicines, over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, or dietary supplements are used by 80% of adults. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices reports that 33% of adults take at least five medications daily.

Medication errors are the most frequent malpractice claims against hospitals and nurses, costing about $5000 per error. More than $3 million is awarded (on average) by the courts for serious errors. The cost of the patient and family suffering is not calculable.

The focus of this chapter is the Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN) initiative as it relates to safe medication administration and prevention of medication-related errors. The six QSEN competencies focus on patient/family–centered care, collaboration and teamwork, evidence-based practice, quality improvement, safety, and informatics. (Refer to Chapter 11 and the QSEN website, www.qsen.org.)

“Five-Plus-Five” Rights of Medication Administration

The rights of medication administration are the foundation for medication safety. The nurse following the original five rights of medication administration will give (1) the right patient the (2) right drug (3) in the right dose via (4) the right route at the (5) right time. Experience shows that five additional rights are essential to professional nursing practice: (1) right assessment, (2) right documentation, (3) patient’s right to education, (4) right evaluation, and (5) patient’s right to refuse.

The right patient determination is essential. The Joint Commission (TJC) requires two forms of identification before administration of the medication. Some patients are unable to respond or answer to any name, so the nurse must verify patient identification each time he or she administers a medication.

Nursing implications include the following:

The nurse must be sure that the right drug is administered. Medication orders may be prescribed by any licensed health care provider (HCP) having authority from the state to prescribe drugs. These include a physician (MD), dentist (DDS), podiatrist (DPM), advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), or physician assistant (PA). In some health care settings, medical students write drug orders; these orders must be countersigned by an attending or staff physician or other prescribing health care provider before they are considered official. The law requires that handwritten prescriptions be written on a tamperproof prescription pad and filled by a pharmacist at a drugstore or hospital pharmacy. Depending on agency policy, drug orders may be written on order sheets and signed by the duly authorized person. A telephone order (TO) or verbal order (VO) for medication must be “read back” to the HCP as an accuracy check and cosigned by the prescribing health care provider within 24 hours. The nurse must comply with the institution’s policy regarding a TO, which sometimes requires that two licensed nurses listen to and sign the order.

As part of the electronic health record (EHR), prescriptions may also be entered directly into the patient’s record, electronically signed by the HCP, sent directly to the pharmacy, and recorded as part of the patient record. A strong safety feature of the EHR is the ability to identify untoward drug interactions with the patient’s current drugs and the newly prescribed/ordered medications. The EHR has decreased medication errors by eliminating some opportunities for errors such as transcription errors.

The use of computerized order systems has added speed and a safety feature to the order process. Orders can be written from virtually any location and sent electronically. The computer will not process the order unless all necessary information is included. Because the order is computerized, illegible orders or signatures are prevented.

The components of a drug order are as follows:

• Date and time the order is written

• Drug name (generic preferred)

• Frequency and duration of administration (e.g., × 7 days, × 3 doses)

• Physician or other health care provider’s signature or name if TO or VO

Although the nurse’s responsibility is to administer drugs as ordered, the drug order is incomplete and the drug should not be administered if any one of the components is missing. Clarification of a questionable order must be done in a timely manner. The health care provider is usually contacted, and the conversation content is documented. Nurses must know all of the components of a drug order and question any orders that are incomplete or unclear, give a dosage outside of the recommended range, or are contraindicated by patient allergy or laboratory test results. Nurses are legally liable if they give a prescribed drug and the dosage is incorrect or the drug is contraindicated for the patient’s health status. Once the drug has been administered, the nurse becomes liable for the predicted effects of that drug.

The following is an example of a drug order and its interpretation:

1/1/14, 1010 Lasix 40 mg, PO, daily [signature]. (Give 40 mg of Lasix by mouth daily.)

To avoid drug error, the drug label should be read three times: (1) at the time of contact with the drug bottle/container or the prepackaged drug unit, (2) before measuring the drug, and (3) after measuring the drug. First dose, one-time, and “as needed” (PRN) medication orders should be checked against the original orders. Nursing interventions related to a drug order include the following:

• Know the patient’s allergies.

• Know the reason the patient is to receive the medication.

• Check the drug label three times before administration of the medication.

The right dose refers to verification by the nurse that the dose administered is the amount ordered and that it is safe for the patient for whom it is prescribed. The right dose is based on the patient’s physical status, including renal and hepatic function. Renal and hepatic function are important considerations because many drugs are cleared through the kidneys and metabolized by the liver. Patient weight is another important consideration in multiple contexts, such as pediatrics and many medical, surgical, and critical care situations. In most cases, the right dose for a specific patient is within the recommended range for the particular drug. Nurses must calculate each drug dose accurately (see Chapter 14).

Before calculating a drug dose, the nurse should have a general idea of the answer based on knowledge of the basic formula or ratios and proportions. Recheck the calculation of drug doses if a fraction of a dose or an extremely large dose is calculated. Consult a peer or a pharmacist whenever doubt exists.

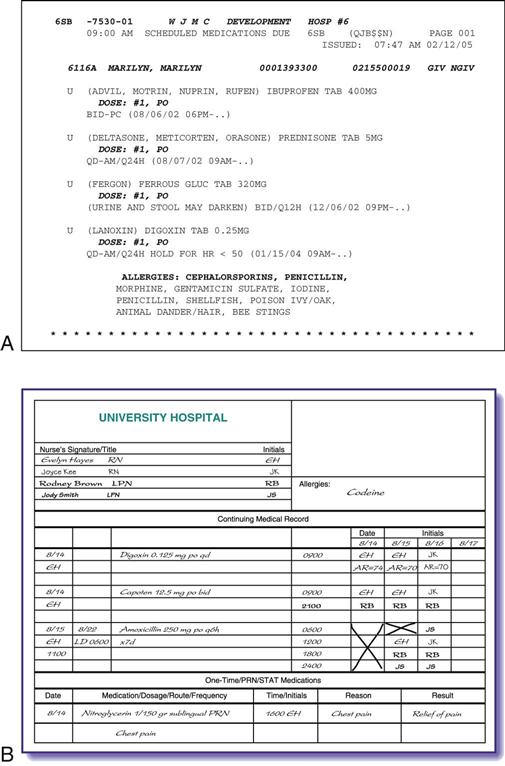

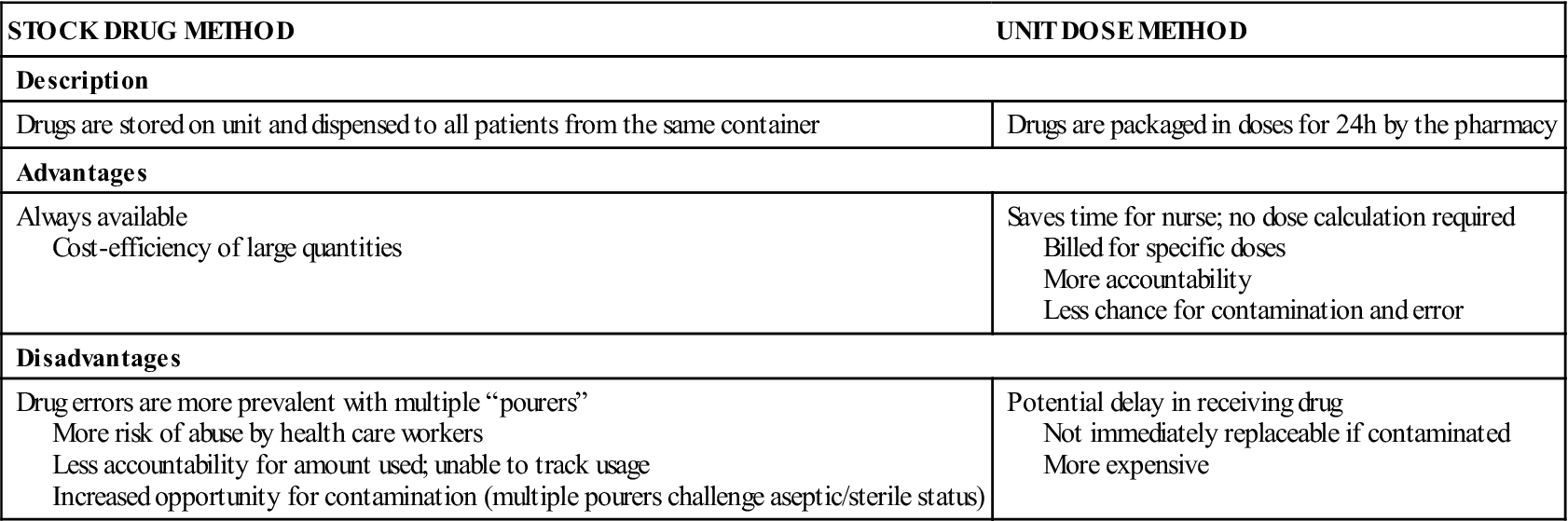

The stock drug method and unit dose method are the two most frequently used methods to dispense drugs (Table 12-1). In the traditional stock drug method, the drugs are dispensed to all patients from the same containers. In the unit dose method, drugs are individually wrapped and labeled for single doses for each patient. The unit dose method, which is popular in many institutions and community settings, has reduced dosage errors because no calculations are required.

TABLE 12-1

| STOCK DRUG METHOD | UNIT DOSE METHOD |

| Description | |

| Drugs are stored on unit and dispensed to all patients from the same container | Drugs are packaged in doses for 24 h by the pharmacy |

| Advantages | |

| Always available Cost-efficiency of large quantities | Saves time for nurse; no dose calculation required Billed for specific doses More accountability Less chance for contamination and error |

| Disadvantages | |

| Drug errors are more prevalent with multiple “pourers” More risk of abuse by health care workers Less accountability for amount used; unable to track usage Increased opportunity for contamination (multiple pourers challenge aseptic/sterile status) | Potential delay in receiving drug Not immediately replaceable if contaminated More expensive |

Automated dispensing cabinets assist the nurse in correctly and quickly administering medications. This technology improves patient care by promoting accurate and quick access to medications, locked storage for all medications, and electronic tracking for controlled substances. Pharmacists can review orders using a link to the pharmacy information system and current clinical patient data, interface with other databases (e.g., the laboratory), and bar-code doses. Automation of medication administration saves time, decreases costs associated with the administration of medications, and allows the ability to automatically collect documentation information. An activity report menu is a useful feature. Flexible dose modes are available, including single-dose, multi-dose, and multiple medications.

Nursing interventions related to the right dose include the following:

The right time is the time the prescribed dose is ordered to be administered. Daily drug dosages are given at specified times during a day, such as twice a day (b.i.d.), three times a day (t.i.d.), four times a day (q.i.d.), or every 6 hours (q6h), so that the plasma level of the drug is maintained at a therapeutic level. Every drug cannot be given exactly when ordered; therefore, health care agencies have policies that specify a range of times within which drugs can be administered before or after the appointed time. When a drug has a long half-life ( ), it is usually given once a day, although many depot preparations have a

), it is usually given once a day, although many depot preparations have a  of days. Drugs with a short

of days. Drugs with a short  are given several times a day at specified intervals. Some drugs are given before meals, and others are given with meals or other food depending on the effect of the gastrointestinal (GI) environment on absorption of the drug.

are given several times a day at specified intervals. Some drugs are given before meals, and others are given with meals or other food depending on the effect of the gastrointestinal (GI) environment on absorption of the drug.

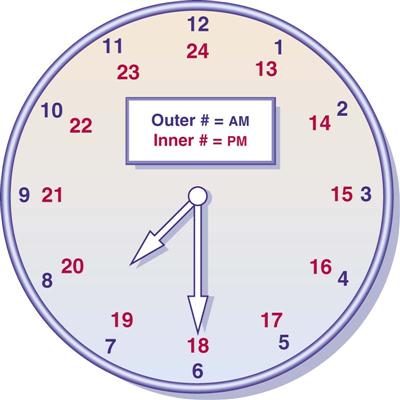

Use of military time reduces administration errors and decreases documentation. Many nursing settings use military time, which is a 24-hour clock. See Figure 12-1 for military time in comparison with standard time. Nursing interventions related to the right time include the following:

The right route is necessary for adequate or appropriate absorption. The right route is ordered by the health care provider and indicates the mechanism by which the medication enters the body. The more common routes of absorption include oral (by mouth): liquid, elixir, suspension, pill, tablet, or capsule; sublingual (under the tongue for venous absorption); buccal (between the gum and cheek); via feeding tube; topical (applied to the skin); inhalation (aerosol sprays); instillation (in nose, eye, or ear); suppository (rectal or vaginal); and five parenteral routes: intradermal, subcutaneous (subQ), intramuscular (IM), intravenous (IV), or intraosseous (IO).

Nursing interventions related to the right route include the following:

• Administer drugs at the appropriate sites for the route.

• Stay with the patient until oral drugs have been swallowed.

The right assessment requires collection of appropriate data before administration of the drug. Examples of assessment data include apical heart rate before the administration of digitalis preparations or serum blood sugar levels before the administration of insulin.

The right documentation requires the nurse to immediately record the appropriate information about the drug administered. This includes (1) the name of the drug, (2) the dose, (3) the route (injection site if applicable), (4) the time and date, and (5) the nurse’s initials or signature. Documentation of the patient’s response to the medication is required with a variety of medications: (1) opioids (How effective was pain relief?); (2) non-opioid analgesics (How effective was pain relief?); (3) sedatives (How effective was relaxation?); and (4) antiemetics (Was nausea/vomiting decreased or eliminated?). Unexpected reactions to the medication (Was there any GI irritation or signs of skin sensitivity?) should also be documented. Patient responses are not necessarily verbal; they could be physiologic (e.g., Did blood pressure go down in response to an antihypertensive? Did LDL cholesterol go down in response to a statin?). Delay in charting could result in forgetting to chart the medication, and another nurse could administer the drug, assuming that the drug was not administered because it was not charted. Do not sign off medications before administration because the medication may not be administered to the patient for some reason. Graphic formats or computerized systems (Figure 12-2) assist in accurate and timely recording of drugs administered.

The right to education requires that patients receive accurate and thorough information about the medication and how it relates to their particular condition. Patient teaching also includes therapeutic purpose, expected result of the drug, possible side effects of the drug, any dietary restrictions or requirements, skill of administration, and laboratory test result monitoring. This right is a principle of informed consent, which is the individual having the knowledge necessary to make a decision. An informed patient and family is critical to preventing medication errors.

The right evaluation refers to an appraisal of a drug’s therapeutic and adverse effects. Evaluation in this context asks, “Did the medication do for the patient what it was supposed to do?” It is essential for the nurse’s practice to evaluate the therapeutic effect of the medication as well as any side effects and adverse reactions. This evaluation is an important aspect of patient safety.

The patient has the right to refuse the medication. Patients can and do refuse to take a medication. It is the nurse’s responsibility to determine, when possible, the reason for the refusal and, if the reasoning is not sound, to take reasonable measures to facilitate the patient’s taking the medication. Explain to the patient the risk of refusing to take the medication, and reinforce the reason for the medication. When a medication is refused, the refusal must be documented immediately, and follow-up is always required. The nurse manager, primary nurse, or health care provider should be informed when the omission may pose a specific threat to the patient, and when a change is expected in the laboratory test values, such as with insulin and warfarin (Coumadin).

Consider all medication errors serious or potentially serious. A medication error may involve one or more of the following: administration of the wrong medication or IV fluid; the incorrect dose or rate; administration to the wrong patient, by the incorrect route, or at the incorrect schedule interval; administration of a known allergenic drug or IV fluid; omission of a dose; or discontinuation of medication or IV fluid that was not discontinued.

Nurses’ Rights When Administering Medications

In addition to the rights of medication administration, there are six rights for nurses who administer medications. These rights provide an additional layer of safety by ensuring that the nurse has what is needed to provide safe medication administration.

The nurses’ six rights are (1) the right to a complete and clear order; (2) the right to have the correct drug, route (form), and dose dispensed; (3) the right to have access to information; (4) the right to have policies to guide safe medication administration; (5) the right to administer medications safely and to identify problems in the system; and (6) the right to stop, think, and be vigilant when administering medications. Discussion of these rights can assist in increasing the safety of medication administration.

The right to a complete and clear order requires that the drug, dose, route, and frequency be ordered by the health care provider. Prescription orders entered directly into a computer ensure that the prescription is legible. However, the nurse must question the health care provider if the order is not complete or is unclear.

The nurse has the right to have the correct drug, route (form), and drug dispensed. Dispensing medications correctly is the role of the pharmacist. Automated medication administration systems may be programmed to allow nurses access to many kinds of medications, rather than the safer unit dose access.

The right to have access to information includes the right to expect current and readily accessible drug information (e.g., hospital formulary, nursing drug reference). This right is a must. Nurses are only to administer drugs with which they are knowledgeable.

Nurses have the right to have policies to guide safe medication administration. Health care administration’s role is to provide the structure on which nurses administer drugs safely. In each facility, policies guide nursing practice. Not following policy or administering medication without policies is not acceptable and places nurses at risk for losing their nursing license.

The right to administer medications safely and to identify problems in the system encompasses nurses’ right and responsibility to speak up when they are first aware of situations that impinge negatively on safe administration of medications. Nurses should be an advocate for safety in the health care setting.

Nurses have the right to stop, think, and be vigilant when administering medications. When unsure, nurses have the right and responsibility to stop and think, consult with other health professionals, and check their institution’s policies. Safety is the basis for these actions.

Culture of Safety

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) classic report of 1999, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System, spurred work on identifying health care system changes to decrease errors. A medication error may be defined as “any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or harm to a patient.”

Possible causes of medication errors include dramatic increase in the number of drugs available; violation of the rights of nursing medication administration; lack of drug knowledge; memory lapses; transcription, dispensing, or delivery problems; inadequate monitoring; distractions; overworked staff; lack of standardization; equipment failures; inadequate patient history; and poor interdepartmental communication.

In response to the escalating number of medication errors causing human deaths and costing billions of dollars, in 2002 the FDA proposed a rule titled Bar Code Label Requirements for Human Drug Products and Blood, which has increased the prominence of this coding. At a minimum, the bar code contains the drug’s national drug code that “uniquely identifies the drug, its strength, and its dosage form.” A revision to this rule eliminates blood and blood products because they have had bar codes since 1985. Most staff embrace bar coding once they are proficient with its use. They note, however, that bar coding is a tool but not a substitute for critical thinking.

Computerized prescriber order entry systems interact with laboratory, pharmacy, and patient data. This integrated system of patient data is the basis for the success of bar coding. With bar coding, the patient’s medication administration record (MAR), a part of the database that is encoded in the patient’s wristband, is accessible to the nurse using a handheld device. After scanning the patient’s wristband, the nurse sees the individual’s MAR on the device. To administer a medication, nurses first scan the drug’s bar code, then the number of the patient’s medical record, and finally the nurse’s own ID badge code. The patient’s MAR is then updated accordingly. (Figure 12-3 shows a nurse scanning a patient’s wristband.) The nurse receives verification on the handheld device of the five rights, warnings, and clinical alerts (e.g., drug is discontinued, drug is not ordered for patient).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree