Angeline Bushy

Rural Health

Focus Questions

What at-risk populations live in rural areas? What are some of their special nursing care needs?

What significant economic, social, and cultural factors affect rural community nursing?

How does rural community nursing differ from practice in more populated settings?

How does a community/public health nurse build a partnership with residents of a rural community?

Key Terms

Farm residence

Frontier

Health professional shortage areas (HPSAs)

Metropolitan

NonMetropolitan

Micropolitan

Noncore-based statistical area

Rural

Urban

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that of the total population, approximately one-fifth (20%) are rural residents who are spread across four-fifths (80%) of the land area. Although a few rural regions are experiencing a decline in population, other small towns have experienced economic revival and population growth (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2009; U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA], 2007a). In the past decade, concerns about access to rural health care service in regions with insufficient numbers of all types of health care providers (designated as health professional shortage areas [HPSAs]) have become a national priority. Those who are concerned with rural health delivery issues are aware of the problems in recruiting and retaining qualified health professionals. Recently, more information has become available on the special challenges, problems, and opportunities of community health nursing in geographically large, sparsely populated areas (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research [AHCPR], 2009; Molinari & Bushy, 2011).

Definitions

The term rural is not easy to define because it means different things to different people. This diversity is a concern among policy makers, researchers, and health care providers alike, because it hampers a coordinated approach to understanding the demographics, epidemiology, and health-related problems of rural communities. A standardized definition of rural is needed for a more coordinated approach to describing clinical problems and addressing health care delivery issues in these settings. Most individuals include geographical and population factors as well as subjective perceptions in their idea of rural versus urban (Cromartie, 2008; USDA, 2006, 2007b; Winters & Lee, 2009).

Geographical Remoteness and Sparse Population

Commonly used definitions for rural refer to the geographical size of an area in relation to its population density or the number of people per square mile. To establish some consensus of viewpoints, common descriptors used by some policy developers include Metropolitan (metro), nonMetropolitan (nonmetro), Micropolitan statistical area, noncore-based statistical areas (Non-CBSA).

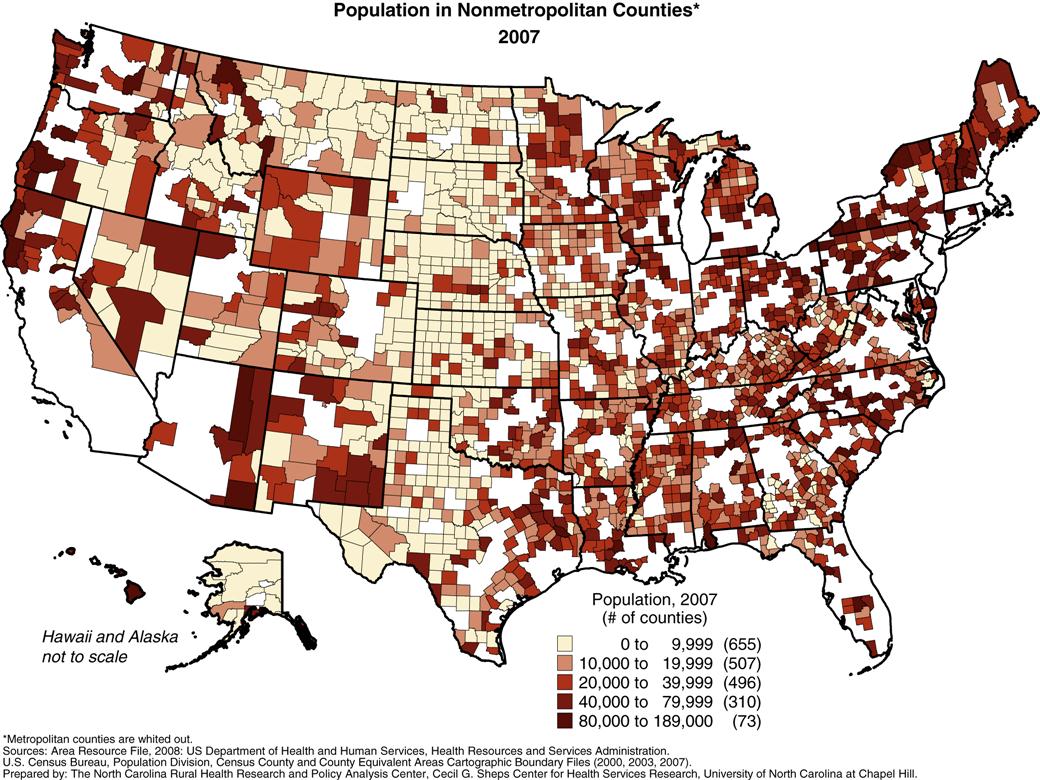

Metropolitanstatistical areas are defined as geographical areas with a core urban area of 50,000 or more population. NonMetropolitanstatistical areas include geographical areas with a core urban area of less than 50,000 or no core urban area. Micropolitanstatistical areas are defined as geographical areas with a core urban area of at least 10,000 but no more than 50,000. Noncore-based statistical areas include geographical areas with a core urban area under 10,000 or no core urban area. Of the total U.S. rural population, approximately 5% live in towns of fewer than 2,500 residents. (Coburn et al., 2007; Office of Rural Health Policy [ORHP], 2002; U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2000;USDA, 2006) (Figure 32-1).

Another classification distinguishes between farm and nonfarm residency. Less than 2% of the total U.S. population has a farm residence. Generally, farm residents are involved in some type of agricultural production. Another set of definitions classifies regions as urban (99 or more persons per square mile), rural (less than 99 persons per square mile, and frontier (six or fewer persons per square mile). In some ways, these terms better illustrate the challenges encountered by a few people living in a very large geographical region.

Another set of definitions for rural takes into consideration the distance and/or time to commute to an urban area to access health care services (e.g., more than 30 minutes or more than 20 miles). However, the factors of time and distance to access services also may be applicable to residents who live in the inner city or, perhaps, a suburban area. For research purposes, the rural-urban continuum offers a classification scheme that distinguishes metro counties by the population size and nonmetro counties by the degree of urbanization associated with adjacency to a metro area. This classification helps to address overlapping and inconsistent definitions of rural versus urban (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011; USDA, 2007b; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010c).

Subjective Perceptions of “Rural”

Some Americans perceive rural areas as those not having access to cable television or high speed internet, whereas others think that any town having a major discount store is an urban center. However, there also are some rather grim rural scenes that are less obvious. For example, on American Indian reservations, most of which are located in rural areas, impoverishment is comparable with that in third world countries. In migrant labor camps, one-room shanties shelter two or more Mexican American families, toilet facilities are lacking, and workers suffer intense exposure to highly carcinogenic herbicides and pesticides. “Boom towns” that spring up overnight in energy-rich regions (i.e., areas with coal, oil, or precious metals) or in vacation-destination communities are not prepared to handle the social problems stemming from the massive influx of outsiders into long-established agricultural communities.

The “typical rural town” is hard to describe because of wide population and geographical diversity. A rural town in Utah is quite different from one in Alaska, Hawaii, or Tennessee. Likewise, there can be many differences among towns in the same state. Legislators’ understanding of a rural area is usually based on the district they represent, and this often is reflected in their decisions.

Furthermore, the various terms used to describe and understand rural residency are relative. For instance, small communities with 10,000 people have some features that one expects to find in a large city; whereas residents living in a community of fewer than 2000 perceive a town with 5000 people as a city. Or, residents in geographically remote areas may not feel isolated because they perceive having urban services within easy reach, either through telecommunication or dependable transportation (Bushy, 2010).

Rural Economic and Population Patterns

Another classification of rural areas created by the federal government provides greater specificity concerning a rural area’s economic climate based on the principal industries in that area. The seven categories of nonMetropolitan counties, based on economic dependencies, are farming dependent, manufacturing dependent, mining dependent, specialized government, persistent poverty, federal lands, and recreational-retirement (USDA, 2005, 2007c, 2007d).

For example, manufacturing-dependent counties are characterized by a larger and denser population, a higher proportion of households with a female head, and a greater proportion of African American residents. In contrast, farming-dependent counties are characterized by a smaller population, fewer persons per square mile, fewer households with female heads, and a higher proportion of older adults. This categorization, based on demographic characteristics, may also lend some insight into a particular community’s health problems (e.g., older adults with chronic illness, younger-than-average population with higher fertility rates, and specific types of occupational hazards and environmental risks, such as farming and ranching with an increase in skin cancer). This approach, however, can falsely lead to a perceived homogeneity of the community, because little consideration is given to subpopulations (underrepresented groups) that also live there (USDA, 2005, 2007c).

Recent census trends indicate some nonMetropolitan areas have experienced a substantial influx of new residents, especially in recreational and retirement counties (USDA, 2007a, 2007c, 2007d, 2007e). Counties experiencing the most rapid rural growth are found in states located in the intermountain west extending from Canada to Mexico, as well as in regions of the Ozarks, the lake country of the upper Midwest, Florida, the Blue Ridge Mountains, and along the outskirts of some thriving Metropolitan suburbs. Population estimates reveal that some rural communities are rapidly expanding with relocated urban residents. Existing local infrastructures and public services are unable to keep pace with the growth. For instance, aging water, sewage, and communication systems; housing units; and schools are inadequate to handle the increased demands associated with the influx of local residents. However, approximately 25% of all nonMetropolitan counties continue to have a declining population. Disproportionately, communities with declining populations are located in the Great Plains, the Corn Belt, and the Mississippi delta and scattered among mining districts across the 50 states. Few data exist that describe either the short- or long-range impact on the health of rural communities caused by the rapid in-migration of formerly urban residents. More is known about the impact on a community experiencing a declining population. One can anticipate, however, that traditional community dynamics will play a role in how long-time rural residents integrate new residents into their communities (McGranahan et al., 2010; USDA, 2007e).

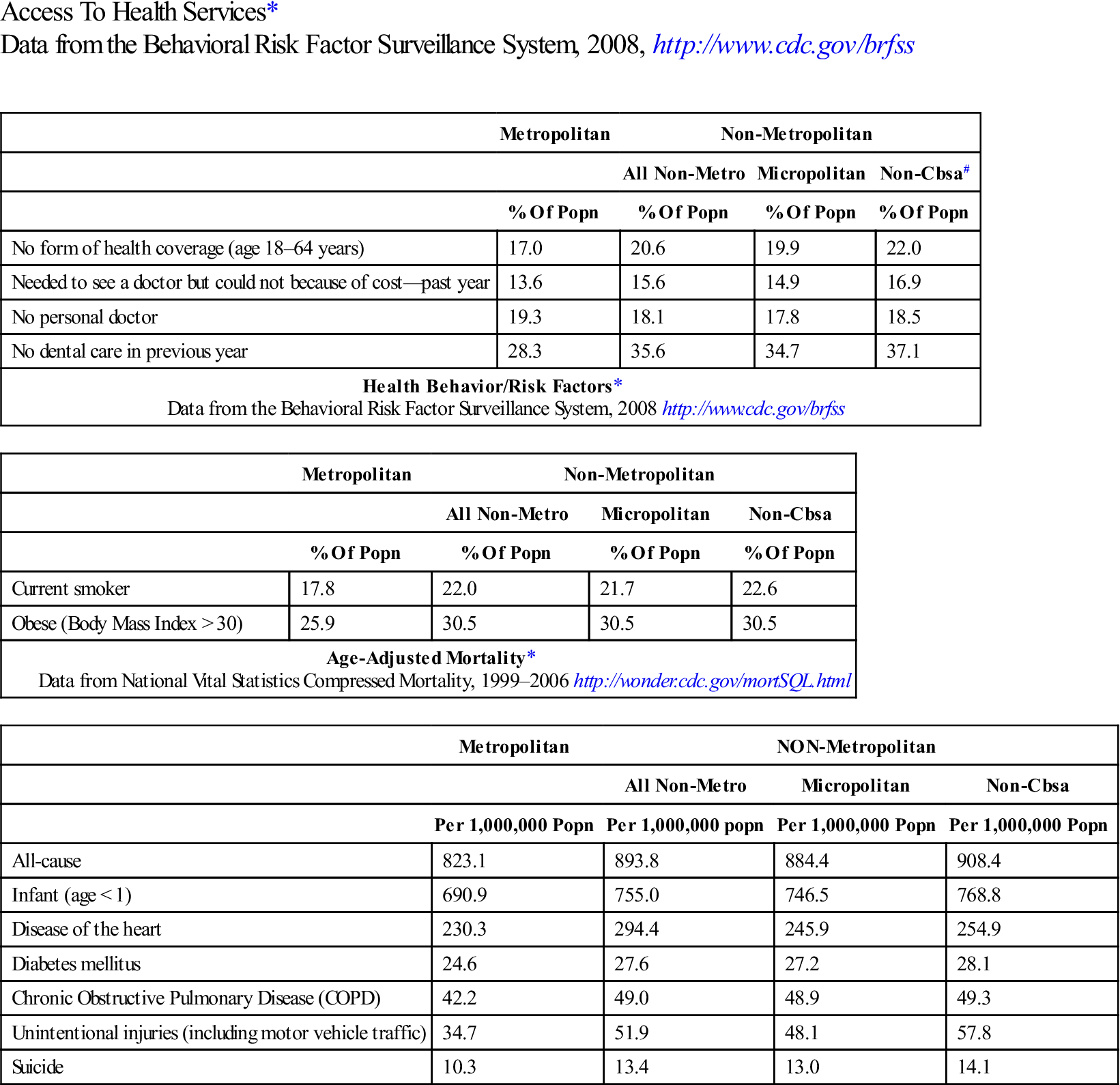

Consistent with national trends, there has been an increase in the proportion of racial minorities in rural areas, and they make up approximately 17% of the rural population (USDA, 2007c). Although not much is known about rural residents in general, even less is known about the subgroups and minorities who live there. Most health information about rural populations focuses on maternal, infant, and older adult populations; such information is easier to assess and monitor because of existing public services. There are regional differences as well as great variations in health status even within a given community. For example, some rural states in the upper Midwest and intermountain area report the best overall pregnancy outcomes. Within those same states, however, American Indians have the poorest outcomes, comparable with those of third world countries. Except for American Indians, many of whom receive care from the Indian Health Service (IHS) (2011a, 2011b, 2011c), adequate descriptions are lacking about the health status of rural minority populations. This is partially attributable to the very small numbers of rural minority group members, for whom data tend not to be extrapolated from large national data sets (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2005) (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1

| Access To Health Services* Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008, http://www.cdc.gov/brfss |

| Metropolitan | Non-Metropolitan | |||

| All Non-Metro | Micropolitan | Non-Cbsa# | ||

| % Of Popn | % Of Popn | % Of Popn | % Of Popn | |

| No form of health coverage (age 18–64 years) | 17.0 | 20.6 | 19.9 | 22.0 |

| Needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost—past year | 13.6 | 15.6 | 14.9 | 16.9 |

| No personal doctor | 19.3 | 18.1 | 17.8 | 18.5 |

| No dental care in previous year | 28.3 | 35.6 | 34.7 | 37.1 |

| Health Behavior/Risk Factors* Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2008 http://www.cdc.gov/brfss | ||||

| Metropolitan | Non-Metropolitan | |||

| All Non-Metro | Micropolitan | Non-Cbsa | ||

| % Of Popn | % Of Popn | % Of Popn | % Of Popn | |

| Current smoker | 17.8 | 22.0 | 21.7 | 22.6 |

| Obese (Body Mass Index > 30) | 25.9 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 30.5 |

| Age-Adjusted Mortality* Data from National Vital Statistics Compressed Mortality, 1999–2006 http://wonder.cdc.gov/mortSQL.html | ||||

| Metropolitan | NON-Metropolitan | |||

| All Non-Metro | Micropolitan | Non-Cbsa | ||

| Per 1,000,000 Popn | Per 1,000,000 popn | Per 1,000,000 Popn | Per 1,000,000 Popn | |

| All-cause | 823.1 | 893.8 | 884.4 | 908.4 |

| Infant (age < 1) | 690.9 | 755.0 | 746.5 | 768.8 |

| Disease of the heart | 230.3 | 294.4 | 245.9 | 254.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 24.6 | 27.6 | 27.2 | 28.1 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) | 42.2 | 49.0 | 48.9 | 49.3 |

| Unintentional injuries (including motor vehicle traffic) | 34.7 | 51.9 | 48.1 | 57.8 |

| Suicide | 10.3 | 13.4 | 13.0 | 14.1 |

*Estimates for Metropolitan compared to all non-Metropolitan counties differ significantly at P <0.05 for all indicators

#Non-CBSA + Non-Core Based Statistical Area

SOURCE: North Carolina Rural Health Research & Policy Analysis Center. http://www.shepscenter.unc.edu/research_programs/rural_program/pubs/other/RuralHealthSnapshot2010.pdf.

Both out-migration and in-migration can create problems that, in many instances, a small town cannot solve because of the lack of resources. For example, population shifts disrupt long-established informal “helping networks,” creating a need for unusual kinds of human services for localities, such as support services for abused women, parenting classes, and crisis intervention teams. Despite the need, public health programs, community nursing, and mental health services often are not available, accessible, or acceptable to target groups in rural areas.

Status Of Health In Rural Populations

Rural Initiatives: Healthy People 2020.

In general, rural areas can be described as “bipolar”—that is, most residents are either younger than 17 years or older than 65 years. In turn, the demographics are reflected in the health status and health care needs of residents in a particular community (see the Healthy People 2020 box on the following page). Rural Healthy People 2010: A Companion Document to Healthy People 2010 (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004) was developed to correspond with Healthy People 2010. It remains to be seen if such a corresponding rural document will be developed for Healthy People 2020. (Bellamy et al., 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2010a). Rural Healthy People 2010 identified and prioritized the health care needs of at-risk populations; specifically migrant workers, blacks, American Indians and other American natives, Asians, and Pacific Islanders, as well as pregnant women, children, and older adults. (Refer to Chapters 10 and 21 for additional information.) In spite of the contributions offered by this rurally focused initiative, there continues to be a serious gap in data on the health status of vulnerable and at-risk rural populations, particularly minorities (Bennett et al., 2008; IOM, 2005; Mead et al., 2008; National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services [NACRHHS], 2011).

In general, the literature indicates that, compared with urban Americans, rural people:

• Have higher infant and maternal morbidity rates;

• Have higher rates of chronic illnesses, such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease;

• Have high rates of mental illness and stress-related diseases (especially among the rural poor);

• Are less likely to have health insurance with pharmacy coverage plans;

• Spend 25% more on prescription drugs than those in cities (North Carolina Rural Health Research & Policy Analysis Center, 2010; USDHHS, 2010a).

Rural Homelessness and Poverty

Homelessness is not unique to urban areas. The rural homeless face some health problems specific to their locale. For instance, rural homeless people often are families from the community who had their farms or businesses foreclosed. Sometimes they are able to continue living in their houses, depending on the law, but they no longer have a means of livelihood and therefore are without any income to purchase food or services. However, most are not able to remain in foreclosed properties and are truly homeless. Two major groups of rural homeless people are migrant workers and families who are poor (USDA, 2007c).

Migrant Workers

Migrant farmworkers travel from one work site to another in different states to seek employment in the agriculture industry. Many of them are documented immigrants holding Citizenship and Immigration Services-issued green cards, permitting them to work in the United States. There are, however, a significant but imprecise number of migrant workers and seasonal workers (those who remain in one location throughout the year) who are undocumented. As a group, generally they are Latinos who work, live, and sleep together as they travel along one of several migrant streams starting and ending in Mexico and the Caribbean. The group often includes extended family members of several generations who live and travel in an older-model vehicle. They work for very low wages, and many send part of their salary to family members who remain in their country of origin. Migrant workers currently are receiving a great deal of national attention in discussions related to public assistance and health care. Policies regarding these federal initiatives have implications for public health. Additional information on migrant farmworkers can be found in the reference section and in Chapter 21 (National Center for Farmworker Health [NCFH], 2011; Occupational Safety and Health Administration [OSHA], 2011).

The Poor

Poverty is on the rise in the United States, and racial and ethnic minorities have a higher prevalence of poverty and lower health status than whites (Bennett et al., 2008). Economic conditions in a region definitely affect the health status of the people who live there. For instance, unemployment and underemployment have left millions of Americans unable to afford medical insurance, which perpetuates the problem of lack of insurance or underinsurance among families (see Chapters 4 and 21). More than 50% of the medically underinsured live in nonurban areas. National estimates report more than 40% of all rural families live below the poverty level. Although minority children represent about 20% of the rural population, they are more likely to live in poverty than their urban counterparts. These children experience substandard housing, poor sanitation, inadequate nutrition, contaminated water, and lack of public health services, particularly prenatal care, immunizations, health screening, and health education (IHS, 2011b; NCFH, 2011; Rand Corporation, 2010a, 2010b; USDHHS, 2010a, 2010b).

Prevention Behaviors

Overall, rural adults are less likely than urban adults to engage in preventive behaviors such as obtaining regular blood pressure checks, Pap smears, or breast examinations. Also, higher percentages of rural adults engage in risk behaviors such as smoking and not wearing seat belts, which have implications for their overall health status (American Legacy Foundation, 2009; Swaim & Stanley, 2011; York et al., 2010). Some experts speculate that these persistent lifestyle behaviors are associated with inadequate health-promotion education by properly prepared health professionals, of which there are too few in rural areas. Still others speculate that the health-promoting information that is disseminated is not culturally appropriate for rural consumers. Consequently, the information that is distributed does not lead to behavior changes. More research is needed on the health beliefs and practices of rural communities to develop culturally and linguistically appropriate services for those communities (Curtis et al., 2011; Hendricks & Hendricks, 2010; National Center for Health Statistics [NCHS], 2010; USDHHS, 2010a).

Family Services

Family planning, maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health care services are lacking in rural areas. As with the larger health system, maternal and infant health services in the United States are an ironic mixture of superb medical care for some segments and inadequate care for many minorities and economically deprived individuals. Like their Metropolitan counterparts, poor rural families face significant barriers to adequate maternal and infant health care. However, rural families face additional problems, including greater travel distances and difficulty in maintaining comprehensive health services, especially for pregnant women, infants, and children.

Although many regional differences exist, generally there are higher rates of maternal and infant mortality and morbidity in rural areas than in urban areas, especially among racial minorities. This biostatistic reflects social, genetic, economic, and environmental factors that prevail in rural communities. For instance, social factors include a group’s religious belief system regarding the appropriate time for a pregnant woman to seek professional prenatal services. A genetic factor is exemplified by the predisposition of African Americans to sickle cell anemia. Environmental factors include contaminated water, air pollution, or pesticide to which a migrant worker who is young and pregnant may be exposed. Less-than-optimal pregnancy outcomes, however, can also be attributed to impaired access to and availability of obstetric and pediatric providers and services (Curtis et al., 2011; Hendricks & Hendricks, 2010; NCHS, 2010; USDHHS, 2010a).

In recent years, there has been a marked reduction in the number of family planning and maternal and child care providers and services in nonMetropolitan areas. Despite an overall increase in the number of obstetricians, pediatricians, and family/general practitioners in the United States, many children and pregnant women face a shortage of providers and services. This can be attributed partly to the high cost of malpractice insurance and partly to the fact that health care providers are not equitably distributed in rural geographical areas. This leaves some areas of the United States without any—or with an insufficient number of—health professionals (Bureau of Health Professions [BHPR], 2010; Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS], 2011; National Health Service Corps [NHSC], 2011; National Rural Health Association [NRHA], 2011).

In some regions of the United States, for example, some pregnant women must travel more than 150 miles one way to obtain care from an obstetrician. Traveling long distances for care also may be required for children with disabilities because specialists usually practice in urban areas. Consequently, pregnant women living in rural areas, especially minorities, are less likely to initiate care during the first trimester, and their children with special needs are less likely to receive rehabilitative and restorative care (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004; Swaim & Stanley, 2011).

Closure of rural hospitals and their obstetric units has had an adverse effect not only on access to services but also on pregnancy outcomes. Hospital closures in rural areas often are associated with depressed local economies and inequitable third-party reimbursement policies. More recently, the development and expansion of large health care systems have also led to closures of small and rural hospitals, buying out small hospitals and physician practices. When these health care systems enter the community, local residents are told that outreach health care services will be provided. Because the numbers of rural residents are small and because the overall health of rural residents is poor, services to these communities are not as profitable as initially projected. To cut costs and improve profits, outreach services to rural communities may be reduced or eliminated, leavings already underserved communities with even fewer providers. The impact of health care systems on rural communities poses many unresolved and serious concerns. Data are currently being collected to assess the effects of this particular phenomenon on the health of rural communities (CMS, 2011; NHSC, 2011; Ortiz & Bushy, 2011).

Women who live in communities with relatively few obstetric providers, for example, are less likely to deliver in their local community hospitals than are those who live in communities with a higher ratio of providers. Moreover, women who must leave “high-outflow” communities to deliver have been found to have a higher rate of complicated and premature births, which has been attributed to delays in seeking prenatal care early in pregnancy and inadequate health education (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004).

Mothers and infants living in professionally underserved areas remain in the hospital longer after delivery because of the distance of the hospital from their home and the potential need for emergency services. For example, a new mother who lives more than 100 miles from the hospital and must contend with ice and snow on a county road to reach her home is less likely to be discharged with her new infant after 24 hours than one who lives in the town in which the hospital is located.

Higher rates of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity among rural individuals cannot be attributed entirely to geographical distances and delays in securing health care. As mentioned earlier, rural areas suffer from higher rates of poverty and lower percentages of families with health insurance. Rural states historically have had more restrictive qualification criteria for public assistance. Likewise, welfare reform that limits the time one can receive benefits has had mixed results in rural areas. Particular rural concerns include fewer educational and employment opportunities and limited child care services for those trying to get off public assistance (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004; Mead et al., 2008; NCHS, 2010).

Major Health Problems

There are regional differences in the predominant health problems in rural communities, depending on environmental, genetic, industrial, and socioeconomic factors. Compared with urban areas, there are wider variations in rural areas in the rates of accidents, trauma, chronic illness, suicide, homicide, and use of alcohol and drugs, especially among some minority groups (Bellamy et al., 2011; Curtis et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2011; National Association for Rural Mental Health [NARMH], 2011).

Accidents and Trauma

Trauma and violence pose serious threats of death and long-term disability in Americans, especially adolescent and young adult males. The leading cause of adolescent death is automobile accidents. Annually, thousands of others are severely injured because of alcohol-related accidents. In the United States, there are more than 200,000 individuals with trauma-induced paraplegia, with a significant proportion who are between 15 years and 24 years of age (CDC, 2010a). Rural populations suffer more injuries from lightning, farm machinery, firearms, drowning, and accidents involving vehicles such as boats, snowmobiles, motorcycles, and all-terrain vehicles; separate morbidity and mortality data are often unavailable for such accidents.

Occupational health is a significant concern. Of the four most dangerous industries (agriculture, fishing, mining, construction), proportionally agriculture has the highest morbidity and mortality rates, even though the number of persons actively engaged in farming has decreased. Not only is agricultural work inherently dangerous, but it must also be performed under adverse conditions, such as snow, mud, and extreme heat or cold, and workers must endure long hours. The agricultural labor force is extremely diverse with respect to age, work experience, education, and literacy levels. Many agricultural enterprises are family operated: spouses, children, and other relatives often help with the work without much regard to competency, training, or safety. Similarly, migrant workers (many of whom cannot read English) often consist of women and children of various ages who spend long hours working in fields without having been given Occupational Safety and Health Administration safety briefs (Curtis et al., 2011; Hendricks & Hendricks, 2010; NCFH, 2011). Thus, agriculture has the highest number of injuries and deaths among children of all industries (OSHA, 2011; Stein, 1989; USDA, 2009).

The number of agricultural accidents among women and children and the impact on the family when the male head of the household is involved in a serious injury or death are unknown. Family businesses are small, so they do not have workers’ compensation insurance. Because health professionals are scarce, education regarding safety and injury prevention becomes an important responsibility of community health nurses who practice in rural communities (Davis & Droes, 1993; Hurme, 2009; OSHA, 2011).

Chronic Illness

Rural residents in general have a relatively low mortality rate but a high rate of chronic illness. The increase in long-term health problems can be attributed to the greater percentage of poor older adults and other at-risk populations, poorer pregnancy outcomes, and the long-term consequences of nonfatal accidents. Critically needed services in rural areas include preventive services such as health screening clinics and nutrition counseling and tertiary prevention that addresses prevalent chronic health problems. To provide care to those who have chronic health problems, there is an ever-increasing need for adult daycare, hospice and respite care, homemaker services, and meal deliveries to help chronically ill individuals who remain at home in geographically isolated areas (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004; NACRHHS, 2011; USDA, 2007a, 2007d). Community health nurses in rural areas can be instrumental in advocating for the provision of such services.

There are special challenges in providing acute care services for the chronically impaired because there has been a higher rate of closures among rural hospitals. For example, an out-of-community transfer of even one care provider, most often a physician, can mean that a small hospital must close its doors because of insufficient staff. The limited supply of and increasing demand for health professionals in general, and nurses in particular, will continue for some time. This shortage has a detrimental impact on the continuum of care to the rural and chronically underserved impaired and creates an even greater demand for community health nurses (IOM, 2005, 2011; Skillman et al., 2007).

Providing care to the chronically ill requires a move away from specialized acute curative medicine to a continuum of health care services. In rural areas, because of the shortage of health care services, more facilities and personnel are needed to achieve an adequate level of service. Existing programs in urban as well as rural areas must become more effective by decentralizing services, providing more home services, and using mobile units. Nurses can have an important role in helping to address these concerns by providing available, accessible, and acceptable services. Legislation that provides for direct third-party reimbursement for care provided by advance practice nurses has been slow (Bushy, 2010; Molinari & Bushy, 2011; Nelson & Stover-Gingerich, 2010).

Suicide and Homicide

Nationwide, among those 15 to 24 years of age, homicide and suicide are the second and third leading causes of death (USDHHS, 2011). Each year, more than 5000 youths are murdered, and probably an equal number commit suicide. Homicide is more likely to take place in the inner city, whereas suicide is more prevalent in suburban and rural settings. In the past two decades, there has been an upsurge in the rural suicide rate, especially among male adolescents and young men (Gamm & Hutchison, 2004; NARMH, 2011; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2011).

Associated with the cluster or “copycat” phenomenon in self-inflicted death, in several towns the suicide rate has reached epidemic proportions, with three or more suicide incidents occurring in a very short time. In small towns or rural areas, where most people are fairly well acquainted with one another, a sudden death can be devastating to students and to the community as a whole. Many reasons are cited for the rise in rural suicides, in particular among Native Americans and Native Alaskans, including socioeconomic conditions, changing community social structures, higher levels of drug and alcohol use, and lack of counseling and other social services. Community health nurses have an important role in educating the community to recognize self-destructive and risk-taking behaviors and advocating for crisis interventions to prevent those activities (Bennett et al., 2008).

Alcohol and Drug Use

Facts associated with illicit substance use by rural Americans include:

• Arrests for drug abuse violations have increased significantly in rural areas.

• Arrests for the use of cocaine, heroin, and methadone have increased in rural areas.

• A high proportion of prison inmates in rural states abused alcohol, other drugs, or both.

• In rural areas children as young as 11 and 12 years of age are drinking as many as 14 to 18 beers on weekends (SAMHSA, 2011; Swaim & Stanley, 2011).

In spite of the growing need, there are fewer behavioral health care providers and services available per capita in rural areas who can address chemical and substance abuse. Consequently, community health nurses in rural settings should assume a proactive role with the community in planning, implementing, and evaluating primary prevention and follow-up intervention programs to educate the public about responsible alcohol consumption behaviors (NARMH, 2011; SAMHSA, 2011).

Factors Influencing Rural Health

Rural Health Care Delivery Issues

Policy makers are attempting to identify ways to equitably allocate acute and primary preventive services among all Americans, especially those living in HPSAs located in both rural counties and the inner city. Community health nurses and those who provide outreach services to rural communities should be aware of concerns regarding the availability, accessibility, and acceptability of services. These interrelated delivery issues have serious implications for planning, implementing, managing, and evaluating community nursing services that target rural clients (Bushy, 2009; Winters & Lee, 2009).

Availability of Services

Availability refers to the existence of services and sufficient personnel to provide those services. In rural areas, there are fewer physicians and nurses in general, as well as fewer family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, and specialists, especially obstetricians, pediatricians, psychiatrists, and social service professionals. Economically speaking, a sparse population limits the number and array of services in a given region. The per capita cost of providing special services to a few people often becomes prohibitive (i.e., economies of scale).

Accessibility of Services

Accessibility refers to the ability of a person to obtain and afford needed services. Accessibility of health care to rural families may be impaired by the following:

• Lack of public transportation

• A shortage of health care providers

• Inequitable reimbursement policies (e.g., diagnosis-related groups for Medicare)

• Unpredictable weather conditions

Consider the case of a rancher with a high income who lives in a medically underserved frontier area of the United States and has a sudden heart attack. He may not have access to the most basic emergency care, although he has comprehensive medical insurance (Fan et al., 2011).

Access to funding sources to implement public health programs can be hampered by a lack of “grantsmanship.” Successful grant writing requires practice and collaborative efforts between agencies to produce a fundable project. Political forces in small towns often oppose outside help because a grant writer is unable to quantify the immediate benefits to the local community of a proposed public health program for which funds are being sought. For example, the community may express explicit preference for local government interventions and opposition to the perceived meddling of federal or state bureaucracies. A grant proposal to implement an innovative program to address the community health care needs of local subpopulations may not be supported by formal and informal community leaders. In rural areas power is often vested in an elite segment of the community. These individuals frequently remain unaware of the needs of the underprivileged and if a minority may have more power than numerically greater ethnic groups in the community (Bushy, 2010). This insensitivity to others’ needs on the part of community leaders often reinforces the stigma of seeking public assistance. For example, a family who needs public services may avoid using these (even when available and accessible) out of concern that someone in town will tell others they need help. Community health nurses must recognize the stigma attached to the use of certain services, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing, family planning, and chemical dependency services.

Acceptability of Services

Acceptability refers to the degree to which a particular service is offered in a manner congruent with the values of a target population. Given the wide diversity among rural families, acceptability of available community nursing services can be hampered by any of the following:

Many health professionals, including community health nurses, are educated in urban settings having most, if not all, of their clinical experiences there, and may not be exposed to rural clients. When coupled with the stress experienced by rural clients seeking publicly funded care, cultural insensitivity can exacerbate a rural individual’s mistrust of health professionals. Ultimately, a nurse’s attitude affects the long-term health status of a client who may be embarrassed about his or her health problems. Embarrassment often is evidenced by a client’s minimizing symptoms of illness and not seeking care when it is needed (i.e., health care is primarily sought for an acute illness or in an emergency). Faculty in nursing education programs should expose students to the rural environment and the people who live there. Rural student clinical experiences will do much to create a climate of mutual sensitivity and trust between community health nurses and rural clients (Molinari & Bushy, 2011).

Legislation Affecting Rural Health Care Delivery Systems

Box 32-1 highlights some of the major legislation that has affected rural health care delivery. In rural communities, the issues of accessibility, availability, and acceptability of services and providers must always be considered when legislation is implemented. A program that is highly effective in a more populated area rarely can be lifted and transplanted as-is to a rural environment. In some cases, legislated programs have resulted in highly innovative approaches that serve the population well. In other cases, mandated programs simply create other barriers that deter rural populations from using a much-needed service.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree