Chapter 19 Rheumatology

Basic concepts

2 What are the components of a diarthrodial joint and which sites within a diarthrodial joint are vulnerable to disease?

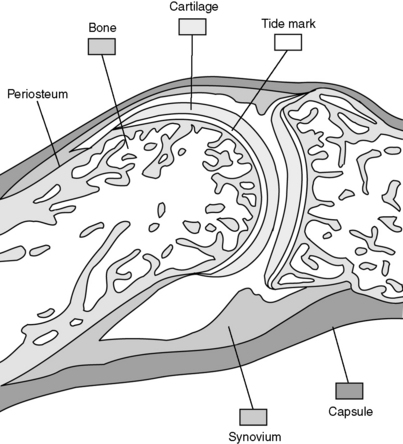

These joints are composed of articulating bones covered by cartilage (usually hyaline cartilage). A fibrous capsule surrounds and protects the joint. The diarthrodial joint cavity is lined with a synovial membrane, which produces synovial fluid to lubricate the joint space. Ligamentous connections provide support and typically allow for a large amount of movement. Each of these components of the joint may be involved in disease processes (Fig. 19-1).

3 What are synarthrodial and amphiarthrodial joints?

Diarthrodial joints are the most common sort of joint and allow a large degree of motion between bones (examples: knees, hips).

Diarthrodial joints are the most common sort of joint and allow a large degree of motion between bones (examples: knees, hips).

The diarthrodial joint is made up of bone, cartilage, a joint space lined with synovium, synovial fluid, a surrounding capsule, and ligamentous insertions.

The diarthrodial joint is made up of bone, cartilage, a joint space lined with synovium, synovial fluid, a surrounding capsule, and ligamentous insertions.

Synarthrodial joints consist of bones bound together by fibrous tissue and are nearly immobile (example: sutures in skull).

Synarthrodial joints consist of bones bound together by fibrous tissue and are nearly immobile (example: sutures in skull).

Amphiarthrodial joints consist of bones bound together by cartilage and are slightly more mobile than synarthrodial joints (example: pubic symphysis).

Amphiarthrodial joints consist of bones bound together by cartilage and are slightly more mobile than synarthrodial joints (example: pubic symphysis).

1 What is the differential diagnosis?

Case 19-1 continued:

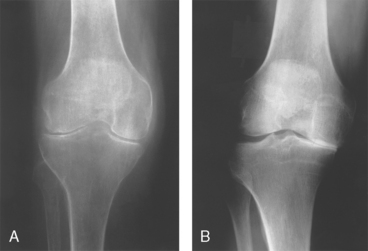

The patient is moderately obese. None of her joints are warm, swollen, or tender. Aside from some crepitus with passive movement, examination of her knees is normal. The proximal and distal interphalangeal joints in both hands are enlarged but nontender. Plain film of the right knee shows narrowing of the medial compartment joint space (Fig. 19-2).

2 What is the likely diagnosis?

Osteoarthritis (also known as OA, osteoarthrosis, degenerative joint disease, hypertrophic arthritis) is likely and is the most common joint disease worldwide. OA is characterized by loss of articular cartilage, which results in damage to the underlying bone. This process results primarily in pain (especially in weight-bearing joints), as well as stiffness and loss of joint mobility. The process is noninflammatory, so there is no ankylosis (fusion) of the joint. Loss of the smooth articulating surface accounts for the finding of crepitus when the joint is moved. Pain is typically worse with use of the joint and decreases with rest. Reactive bone formation resulting in osteophytes (bone spurs) also occurs at the joint margins and may cause slight elevations in serum alkaline phosphatase. Joints typically affected include the proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (Bouchard’s and Heberden’s nodes, respectively), knees, and hips. Figure 19-3 shows both Heberden’s and Bouchard’s nodes. Recall that rheumatoid arthritis typically does not affect the distal interphalangeal joints.

Figure 19-2 Plain film of the knee for patient in Case 19-1.

(From Harris ED, Budd RC, Genovese MC, et al: Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology, 7th ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2005.)

3 Is the pathogenesis of this condition primarily related to degeneration of bone, cartilage, or synovial membrane?

5 What are some risk factors associated with developing osteoarthritis?

Obesity is the strongest modifiable risk factor.

6 Would you expect the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) to be elevated in this patient?

7 How do the findings on x-ray studies generally differ between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis?

Figure 19-4A demonstrates nearly complete loss of the lateral and medial joint spaces in rheumatoid arthritis, whereas Figure 19-4B demonstrates loss of only the medial joint space with subchondral sclerosis (increased density) of the underlying bone in OA.

8 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors are both possible treatments for this patient. What is similar about their mechanisms of action, and what is different?

9 What is the principal therapeutic advantage of the cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors? What can be given to this patient with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug to prevent their principal side effect?

12 What sort of analgesic would you prescribe for a patient with preexisting renal disease? Or liver disease? Or pregnancy?

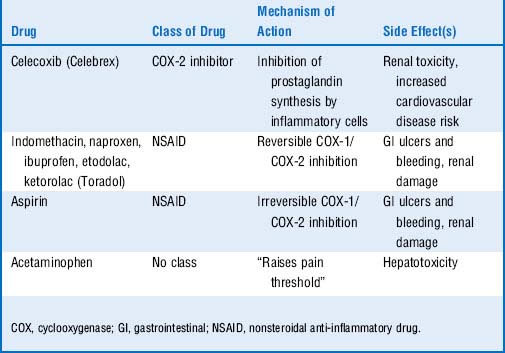

13 Quick review: Look only at the left column in Table 19-1 and try to list the class of drug, mechanism of action, and major side effects for each drug listed

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease worldwide.

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease worldwide.

Although there may be local joint inflammation, it is considered a noninflammatory condition without systemic (constitutional) symptoms.

Although there may be local joint inflammation, it is considered a noninflammatory condition without systemic (constitutional) symptoms.

The disease process is centered in the cartilage and leads to destruction of bone.

The disease process is centered in the cartilage and leads to destruction of bone.

Pain is typically worse with activity.

Pain is typically worse with activity.

Obesity, gender, age, and trauma all contribute to its development.

Obesity, gender, age, and trauma all contribute to its development.

Radiographs show joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes.

Radiographs show joint space narrowing, subchondral sclerosis, and osteophytes.

Acetaminophen, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy.

Acetaminophen, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitors, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy.

1 What is the differential diagnosis?

Case 19-2 continued:

Upon examination, she has symmetrical involvement of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal joints, with sparing of the distal interphalangeals (Fig. 19-5). Involved joints in her hands are swollen, warm, and tender to palpation. She has moderate-sized bilateral knee effusions. Laboratory tests show elevated ESR and CRP and positive rheumatoid factor (RF). She is diagnosed with a chronic autoimmune disease and prescribed methotrexate, an NSAID, and prednisone.

3 What are the criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis?

Four of the following seven criteria must be met for the diagnosis to be made:

1. Morning stiffness lasting at least 1 hour

2. Arthritis of three or more joints

4. Symmetrical joint involvement

8 What would be learned from aspiration of this patient’s knee?

Case 19-2 continued:

Your rheumatoid arthritis patient is lost to follow-up but then returns to your office years later. She complains of diffuse arthralgias, weight loss, and shortness of breath. Her hands appear as shown in Figure 19-6, and subcutaneous nodules are present at the olecranon bilaterally. She has decreased breath sounds at the lung bases, and chest x-ray film shows bilateral pleural effusions and several pulmonary nodules.

9 What are the characteristic deformities in the hands in advanced rheumatoid arthritis?

Destruction of the metacarpophalangeal joints leads to ulnar deviation (shown in Fig. 19-6) as the distal portions of the digits shift toward the ulna. Boutonnière and swan-neck deformities consist of contractions of the fingers at the proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints. Remember that the distal interphalangeal joints are not typically involved with rheumatoid arthritis, though they may be forced into flexion/extension due to involvement of the proximal interphalangeal joints and the tendons of the hand.

Figure 19-5 Appearance of the proximal interphalangeal and metacarpophalangeal joints of the patient in Case 19-2.

(From Goldman L, Ausiello D: Cecil Textbook of Medicine, 22nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2004.)

10 What are the extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis?

Summary Box: Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic inflammatory disease caused in part by immune complex deposition in the joints and potentially various other tissues.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic inflammatory disease caused in part by immune complex deposition in the joints and potentially various other tissues.

Gender, age, and human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) have been associated.

Gender, age, and human leukocyte antigens (HLAs) have been associated.

The disease process is centered in the synovium of the joint.

The disease process is centered in the synovium of the joint.

Joints are typically warm, erythematous, swollen, and tender (synovitis).

Joints are typically warm, erythematous, swollen, and tender (synovitis).

Distal interphalangeal joints are typically spared.

Distal interphalangeal joints are typically spared.

Pain is worse in the morning, classically lasting more than an hour.

Pain is worse in the morning, classically lasting more than an hour.

Rheumatoid factor is an autoantibody, the presence of which confers a poor prognosis.

Rheumatoid factor is an autoantibody, the presence of which confers a poor prognosis.

Extra-articular manifestations include rheumatoid nodules, pericarditis, pleural effusions, pulmonary nodules, pulmonary fibrosis, carpal tunnel syndrome, ocular manifestations, and anemia of chronic disease.

Extra-articular manifestations include rheumatoid nodules, pericarditis, pleural effusions, pulmonary nodules, pulmonary fibrosis, carpal tunnel syndrome, ocular manifestations, and anemia of chronic disease.

Treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). In recent years there has been a strong push to start DMARDs at the time of initial diagnosis.

Treatment includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). In recent years there has been a strong push to start DMARDs at the time of initial diagnosis.

2 How can crystal and septic arthritis be differentiated?

Case 19-3 continued:

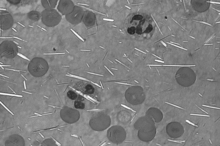

On examination, the right knee is warm, erythematous, swollen, and tender to touch. The patient is afebrile, and the remainder of his examination in unremarkable. You aspirate cloudy yellow fluid from the joint and find 24,000 WBCs, 70% PMNs, and needle-shaped crystals that are strongly negatively birefringent under polarized light (Fig. 19-7).

7 Are there any complications of gout besides the monoarticular inflammatory arthritis?

The classic location for gouty arthritis is in the metatarsophalangeal joint of the great toe, which is known as podagra. In patients with chronic gout, monosodium urate crystals can also deposit in subcutaneous tissues, forming nodules called tophi. Tophi are often found in the helix of the ear and over the elbow. Figure 19-8 shows olecranon bursitis in chronic tophaceous gout. Uric acid calculi may form in the renal pelvis or ureters, leading to obstruction of the urinary tract. Crystals may also cause damage to the renal interstitial tissue, a condition termed gouty interstitial nephropathy.

Figure 19-7 Microscopic appearance of synovial fluid under polarized light aspirated from patient in Case 19-3.

(From McPherson RA, Pincus MR: Henry’s Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods, 21st ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 2006.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree