Responsibilities for Care in Community/Public Health Nursing

Claudia M. Smith

Focus Questions

What is the nature of community/public health nursing practice?

What values underlie community/public health nursing?

How is empowerment important in community/public health nursing?

What health-related goals are of concern to community/public health nurses?

Who are the clients of community/public health nurses?

What are the basic concepts and assumptions of general systems theory?

What is meant by the terms population-focused care and aggregate-focused care?

What are the responsibilities of community/public health nurses?

What competencies are expected of beginning community/public health nurses?

How are community/public health nurse generalists and specialists similar and different?

Key Terms

Aggregate

Commitments

Community-based nursing

Community health nursing

Community/public health nurse

Distributive justice

General systems theory

Group

Population

Population-focused

Professional certification

Public health nurse

Public health nursing

Risk

Social justice

Visions

Imagine that you are knocking on the door of a residential trailer, seeking the mother of an infant who has been hospitalized because of low birth weight. You are interested in helping the mother prepare her home before the hospital discharge of the infant. Or imagine that you are conducting a nursing clinic in a high-rise residence for older adults. People have come to obtain blood pressure screening, to inquire whether tiredness is a side effect of their antihypertensive medications, or to validate whether their recent food choices have reduced their sodium intake. Or picture yourself sitting at an office desk. You are telephoning a physical therapist to discuss the progress of a school-aged child who has mobility problems secondary to cerebral palsy.

Now, imagine yourself at a school parent–teacher association (PTA) meeting as a member of a panel discussion on the prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) transmission. Think about developing a blood pressure screening and dietary education program for a group of predominantly African American, male employees of a publishing company. Picture yourself reviewing the statistics for patterns of death in your community and contemplating with others the value of a hospice program.

Who would you be to participate in all these activities, with people of all ages and all levels of health, in such a variety of settings—homes, clinics, schools, workplaces, and community meetings? It is likely you would be a community health nurse, and you would have specific knowledge and skills in public health nursing.

Note that we have used the terms community health nursing and public health nursing. In the literature, and in practice, there is often a lack of clarity in the use of these terms. Also, the use of these terms changes with time (see Chapter 2). Both the American Nurses Association (ANA, 1980) and the Public Health Nurses Section of the American Public Health Association (APHA, 1980, 1996) agree that the type of involvement previously described is a synthesis of nursing practice and public health practice. What the ANA called community health nursing, the APHA called public health nursing (Box 1-1).

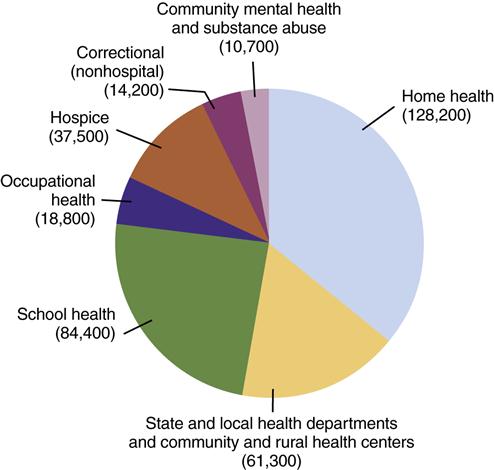

In 1984, the Division of Nursing, Bureau of Health Professions of the Health Resources and Services Administration of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), sponsored a national consensus conference. Participants were invited from the APHA, the ANA, the Association of State and Territorial Directors of Nursing, and the National League for Nursing. The purpose was to clarify the educational preparation needed for public health nursing and to discuss the future of public health nursing. It was agreed that “the term ‘community health nurse’ is … an umbrella term used for all nurses who work in a community, including those who have formal preparation in public health nursing (Box 1-2 and Figure 1-1). In essence, public health nursing requires specific educational preparation, and community health nursing denotes a setting for the practice of nursing” (USDHHS, 1985, p. 4) (emphasis added). The consensus conference further agreed that educational preparation for beginning practitioners in public health nursing should include the following: (1) epidemiology, statistics, and research; (2) orientation to health care systems; (3) identification of high-risk populations; (4) application of public health concepts to the care of groups of culturally diverse persons; (5) interventions with high-risk populations; and (6) orientation to regulations affecting public health nursing practice (USDHHS, 1985). This educational preparation is assumed to be complementary to a basic education in nursing.

Following the logic of the consensus statements, a registered nurse who works in a noninstitutional setting and has either received a diploma or completed an associate-degree nursing education program can be called a community health nurse and practices community-based nursing because he or she works outside of hospitals and nursing homes. However, this nurse would not have had any formal education in public health nursing. Such a nurse may provide care directed at individuals or families, rather than populations (ANA, 2007).

Public health nurses provide population-focused care. Assessment, planning, and evaluation occur at the population level. However, implementation of health care programs and services may occur at the level of individuals, families, groups, communities, and systems (ANA, 2007; Minnesota Department of Health, 2001; Quad Council of Public Health Nursing Organizations, 2004). The ultimate question is: Have the health and well-being of the population(s) improved?

Large numbers of registered nurses are employed in home health care agencies to provide home care for clients who are ill. This text can assist those without formal preparation in public health nursing to expand their thinking and practice to incorporate knowledge and skills from public health nursing.

For those currently enrolled in a baccalaureate nursing education program, this text can assist in integrating public health practice with nursing practice as part of the formal educational preparation for community/public health nursing.

The terms community/public health nurse and public health nurse are used in this text to denote a nurse who has received formal public health nursing preparation. Community/public health nursing is population-focused, community-oriented nursing. Population focused means that care is aimed at improving the health of one or more populations. To save space in the narrative of this text, the term community health nurse is sometimes used instead of community/public health nurse.

Visions and commitments

When describing an object, we often discuss what it looks like, what its component parts are, how it works, and how it relates to other things. Although knowledge of structure and function is important, in interpersonal activities, the exact form is not as important as the purpose of the exchange. And the quality of our specific, purposeful relationships derives from our visions of what might be as well as our commitments to work toward these visions.

Visions are broad statements describing what we desire something to be like. They derive from the ability of human beings to imagine what does not currently exist. Commitments are agreements we make with ourselves that pledge our energies for or toward realizing our visions.

As a synthesis of nursing and public health practice, community/public health nursing accepts the historical commitments of both. By definition and practice, our caring for clients who are ill is part of the essence of nursing. Likewise, we bring from nursing our commitment to help the client take responsibility for his or her well-being and wholeness through our genuine interest and caring. We add, from public health practice, our role as health teacher to provide individuals and groups the opportunity to see their own responsibility in moving toward health and wholeness.

Community/public health nurses are concerned with the development of human beings, families, groups, and communities. Nursing provides us our commitment to assist individuals developmentally, especially at the time of birth and death. Public health expands our commitment beyond individuals to consider the development and healthy functioning of families, groups, and communities.

Public health practice makes its unique contribution to community/public health nursing by adding to our commitments. These commitments include the following:

1. Ensuring an equitable distribution of health care

2. Ensuring a basic standard of living that supports the health and well-being of all persons

These commitments require our involvement with the public and private, political and economic environments.

Boxes 1-3 and 1-4 list the commitments of nursing and public health, respectively, that are grounded in their historical developments. These commitments are the foundations on which specific professional practices, projects, goals, and activities can be created.

Because our culture is biased toward “doing” (being active, being busy, and producing), we often are not conscious of our visions of what might be. We study, exercise, go out with friends, cook, clean, play with children, invest money, and shop. We can get bogged down in “doing” the activities and projects appropriate to our commitments. For example, if you are committed to having relationships with friends, recall a time when a meeting with friends felt like a duty and obligation. You were going through the motions of being together, but you were not genuinely relating to your friends. At that moment, you were not creating the relationship from your commitment; you probably felt burdened rather than enlivened.

Likewise, it is possible to get bogged down professionally by doing the “right” things that public health nurses are supposed to do, but not feeling satisfied. We are disappointed that results do not show up quickly or that suffering persists. We create too many professional projects and feel spread too thin. We burn out.

Working on activities directed toward the commitments underlying community/public health nursing does not guarantee that we will achieve our visions. But not working toward our visions and giving up on our commitments guarantees that we are part of the problem rather than part of the solution in our communities. Not working toward our visions also results in dissatisfaction and disconnectedness.

Remaining in touch with the reasons we are doing something empowers us. Our vision of healthy, whole, vital individuals, families, and communities, as well as our related commitments, can provide a renewing source of energy. And it is hope and energy that we draw on to empower our professional practice and bring vitality to our relationships with individuals, families, and groups.

Expressing our visions and commitments to others provides them an opportunity to become partners in working for what might be. By having partners, we gain support not only for our visions but also for specific projects.

Community/public health nurses often have visions about health that others do not know are possible. Nurses can educate and speak about visions of health and specific commitments that can increase the likelihood of particular health possibilities.

We have discussed two examples of expressing a vision as a basis for creating commitments in nurse–client relationships and in relationships between the nurse and other service providers. It is helpful for each nurse to express his or her visions and commitments to peers and supervisors. As nurses, we need colleagues to encourage us, work with us, and coach us. Work groups whose members can identify some visions common to their individual practices and can agree on some common commitments have a vital source of energy. When we know what we are for, we can assertively invite others to participate with us. When others are working with us, more possibilities are created for synergistic effects.

Distinguishing features of community/public health nursing

Community/public health nurses are expected to use the nursing process in their relationships with individuals, families, groups, populations, and communities (ANA, 2007). Community/public health nursing is the care provided by educated nurses in a particular place and time and directed toward promoting, restoring, and preserving the health of the total population or community. Families are recognized as an important social group in which values and knowledge are learned and health-related behaviors are practiced.

Healthful Communities

What aspects of this definition are different from definitions of nursing in general? The explicit naming of families, groups, and populations as clients is a major focus. Community-based health nurses care for individuals and families. Community/public health nurses also may care for individuals and families; however, they are cared for in the context of a vision of a healthful community. Beliefs underlying community/public health nursing summarized from Chapter 2 are presented in Box 1-5. Community/public health nursing is nursing for social betterment.

Community/public health nurses seek to empower individuals, families, groups, community organizations, and other health and human service professionals to participate in creating healthful communities. The prevailing theory about how healthful communities develop has been that individuals and social groups clarify their identities first and then protect their own rights while also considering the rights of others. More recent studies on the moral development of women in the United States suggest that women first participate in a network of relationships of caring for others and then consider their own rights (Gilligan, 1982).

The ideal for a healthful community is a balance of individuality and unity. Community/public health nurses seek to promote healthful communities in which there is individual freedom and responsible caring for others. It is impossible for an individual to consider only his or her desires without infringing on the freedom of others. For collective well-being to exist, we must also be concerned about caring accountability. We must “ask about justice, about … each person having space in which to grow and dream and learn and work” (Brueggemann, 1982, p. 50). We must ask about the conditions that promote health.

Empowerment for Health Promotion

Because community/public health nurses often work with persons who are not ill, emphasis is placed on promoting and preserving health in addition to assisting people to respond to illnesses. Although not all illnesses can be prevented and death cannot be eliminated, community health nurses seek to empower human beings to live in ways that strengthen resilience; decrease preventable diseases, disability, and premature death; and relieve experiences of illness, vulnerability, and suffering.

Empowerment is the process of assisting others to uncover their own inherent abilities, strengths, vigor, wholeness, and spirit. Empowerment depends on the presence of hope. Power is not actually provided by the community/public health nurse. Empowerment is a process by which possibilities and opportunities for the expression of an individual’s being and abilities are revealed. Nurses can assist in this process by fostering hope and by removing barriers to expression.

Community/public health nurses use the information and skills from their education and experiences in medical–surgical, parent–child, and behavioral or mental health nursing to assist individuals, families, and groups in creating opportunities to make choices that promote health and wholeness. In community/public health nursing, nurses rarely make the choices for others. Instead, as a means of expanding opportunities for others, community/public health nurses provide information about interpersonal relationships and alternative ways of doing things. This is especially true when community/public health nurses instruct others in how to care for those with illnesses or how generally to support the growth and development of other members of families or groups. For example, a husband might be shown how to safely transfer his wife from the bed to a chair, or a young father might be taught how to praise his son and set limits without resorting to threats and frequent punishment.

Being related to people can invite a person to risk being connected and to trust in the face of his or her fears. This is particularly true for those who have experienced intense or patterned isolation, abuse, despair, or oppression. A nurse is said to be “present” with a client when the nurse is both physically near and psychologically “being with” the person (Gilje, 1993). Various ways a community/public health nurse can be “present” are revealed in the case study at the end of this chapter.

Culturally competent care is essential in both public health and nursing practice (ACHNE, 2010; ANA, 2007; Campinha-Bacote et al., 1996; USDHHS, 1997). Community/public health nurses must recognize the diverse backgrounds and preferences of the individuals, families, populations, and communities with whom they work. Cultural influences on health problems, health promotion and disease prevention activities, and other health resources should be assessed. In addition, cultural differences must be considered when developing and adapting nursing interventions.

Theory and community/public health nursing

Nursing practice is based on the concepts of human beings, health and illness, problem-solving and creative processes, and the human–environment relationship (Alligood & Marriner-Tomey, 2010; Hanchett, 1988). Our environment includes physical, social, cultural, spiritual, economic, and political facets.

Our knowledge of these concepts evolves from several routes, including personal experience, logic, a sense of right and wrong (ethics), empiric science, aesthetic preferences, and an understanding of what it means to be human (Alligood & Marriner-Tomey, 2010). Concepts are labels or names that we give to our perceptions of living beings, objects, or events. Theories are a set of concepts, definitions, and hypotheses that help us describe, explain, or predict the interrelationships among concepts (Alligood & Marriner-Tomey, 2010).

Although Florence Nightingale began the formal development of nursing theory, most theory development in nursing has occurred since the 1960s (Choi, 1989). Alligood & Marriner-Tomey (2010) describe the work of numerous nursing theorists. (Obviously, we cannot discuss all of them here.) In community/public health nursing, general systems theory provides a way to link many of the concepts related to nursing. The nursing theories of Johnson (1989), King (1981), Neuman and Fawcett (2002), and Roy (Roy & Andrews, 1999) rely, in part, on general systems theory. Perspectives on client–environment relationships from these theories are discussed later in this chapter.

General Systems Theory

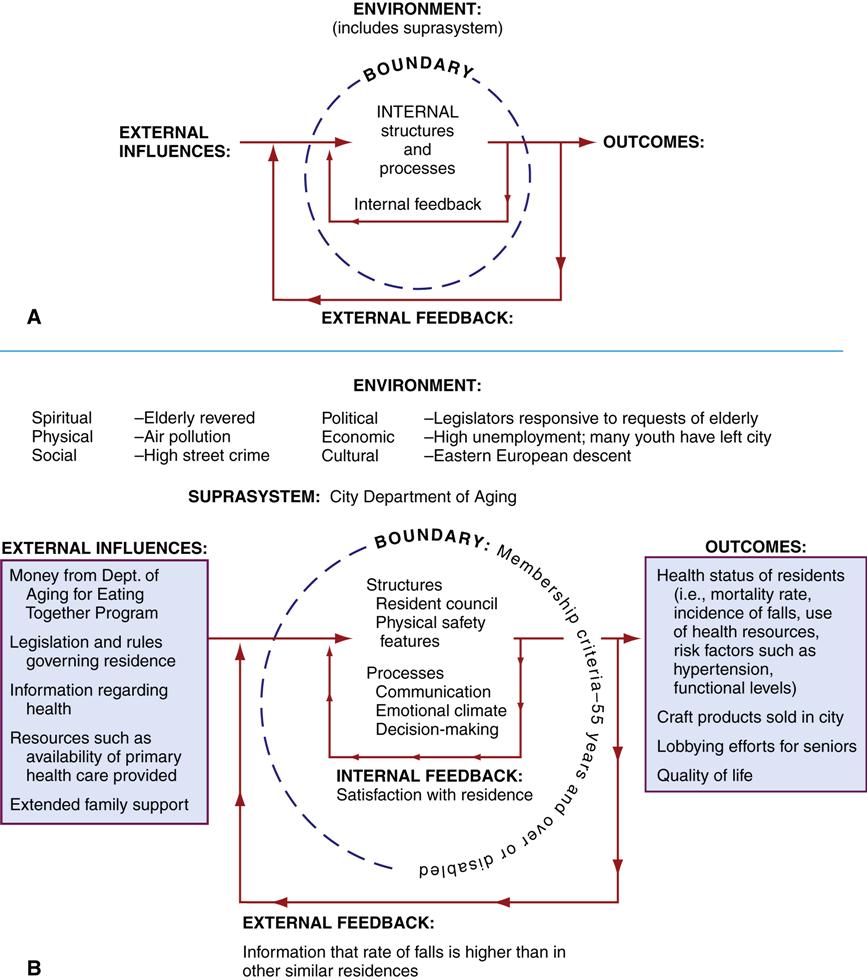

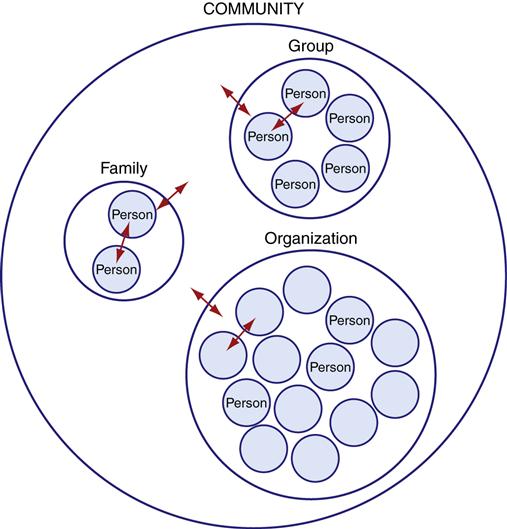

An open system is a set of interacting elements that must exchange energy, matter, or information with the external environment to exist (Katz & Kahn, 1966; von Bertalanffy, 1968). Open systems include individuals as well as social systems such as families, groups, organizations, and communities with whom the community/public health nurse must work (Figure 1-2). Systems theory is especially useful in exploring the numerous and complex client–environment interchanges. For example, a community/public health nurse might provide postpartum home visits to a woman and her newborn, simultaneously focusing on the adjustment of the entire family to the birth. The same nurse might also teach teen parenting classes in a high school and monitor the birth rates in the community, identifying those populations at statistical risk of having low-birth-weight infants.

Compared with inpatient settings, the environments in community/public health nursing practice are more variable and less controllable (Kenyon et al., 1990). General systems theory provides an umbrella for assessing and analyzing the various clients and their relationships with dynamic environments. In this text, family and community assessments are approached from a general systems framework.

Each open system has the same basic structures (Smith & Rankin, 1972) (Figure 1-3, A). Figure 1-3, B, is an example of application of the open system model to a specific organization. The boundary separates the system from its environment and regulates the flow of energy, matter, and information between the system and its environment. The environment is everything outside the boundary of the system. The skin acts as a physical boundary for human beings. A person’s preference for relatedness is a more abstract boundary that helps determine the pattern of interpersonal relationships. Family boundaries might be determined by law and culture, such as a rule that a family consists of blood relatives. A family can have more open boundaries and define itself by including persons not related by blood. Groups, organizations, and some communities have membership criteria that assist in defining their boundaries. Other community boundaries might be geographic and political, such as city limits.

Outcomes are the created products, energy, and information that emerge from the system into the environment. Health behaviors and health status are examples of outcomes. External influences are the matter, energy, and information that come from the environment into the system. External influences can be resources for or stressors to the system. Each system uses the external influences together with internal resources to achieve its purposes and goals. Feedback is information channeled back into the system from its environment that describes the condition of the system. When a nurse tells a mother that her child’s blood pressure is higher than the desired range, the nurse is providing health information as feedback to the mother. Feedback provides an opportunity to modify system functioning. The mother can then decide when and where to seek medical evaluation.

Each system is composed of parts called subsystems. Subsystems have their own goals and functions and exist in relationship with other subsystems. In a human being, the gastrointestinal system is an example of a subsystem. In social systems, the subsystems might be structural or functional. Structural subsystems relate to organization. Examples of structural subsystems are a mother–child dyad in a family or the nursing department in a local health department. Functional subsystems are more abstract and relate to specific purposes. For example, the subsystems of organizations have been conceptualized as production, maintenance, integration, and adaptation (Katz & Kahn, 1966). Subsystems of a community are often named by their function, such as the health care subsystem, the educational subsystem, and the economic subsystem.

Systems might relate as separate entities that interact, or they might create a variety of partnerships and confederations. Systems might be hierarchical. The suprasystem is the next larger system in a hierarchy. For example, the suprasystem of a county is the state; the suprasystem of a parochial school might be the church or the diocese that sponsors the school.

The assumptions that relate to all open systems (von Bertalanffy, 1968) are similar to those underlying holism in nursing (Allen, 1991) and the ecological model of health in public health (Institute of Medicine, 2003):

Nursing Theory

Nursing theories are based on a range of perspectives about the nature of human beings, health, nursing, and the environment. Most nursing theories have been developed with individual clients in mind (Hanchett, 1988). However, many concepts from the different nursing theories are applicable to nursing that addresses families and communities. The concepts of self-care and environment are introduced here.

Self-Care

Self-care is “the production of actions directed to self or to the environment in order to regulate one’s functioning in the interests of one’s life, integrated functioning, and well-being” (Orem, 1985, p. 31). Self-care depends on knowledge, resources, and action (Erickson et al., 1983). The concept of self-care is consistent with the community/public nursing focus on empowerment of persons and groups to promote health and to care for themselves.

Although each person is responsible for his or her own health habits, the family and community have responsibilities to support self-care (USDHHS, 1995). The family is the immediate source of support and health information. The community has responsibilities to provide safe food, water, air, and waste disposal; enforce safety standards; and create and support opportunities for individual self-care (USDHHS, 1995). When the focus is on self-care, the family and community are viewed primarily as suprasystems to individuals.

Client–Environment Relationships

Nursing theories acknowledge that humans live within an environment (Alligood & Marriner-Tomey, 2010). Nurses are caring professionals within clients’ environments and influence clients through direct physical care, provision of information, interpersonal presence, and environmental management. Nursing theories that build on general systems theory tend to place more emphasis on the environment than do other nursing theories (Hanchett, 1988). The continuously changing environment requires that the client expend energy to survive, perform activities of daily living, grow, develop, and maintain harmony or balance. Clients must adapt within a dynamic environment (Table 1-1). (Also see Chapter 9 on environment.)

Table 1-1

Perspectives on Client–Environment Relationships in Selected Nursing Theories

| Theorist | Relationship of Client and Environment |

| Dorothy Johnson | Clients attempt to adjust to environmental factors. Strong inputs from the environment might cause imbalance and require excess energy to the point of threatening the existence of the client. Stable environments help clients conserve energy and function successfully. |

| Sister Callista Roy | Clients attempt to adjust to immediate environmental excesses or absences within a background of other stimuli. Successful adaptation allows survival, growth, and improved ability to respond to the environment. |

| Imogene King | Clients interact purposefully with other people and the environment. Health is the continuous process of using resources to function in daily life and to grow and develop. |

| Betty Neuman | Clients continuously interact with people and other environmental forces and seek to defend themselves against threats. Health is balance and harmony within the whole person. |

Data from Alligood, M., & Marriner-Tomey, A. (2010). Nursing theorists and their work (7th ed.). St. Louis: Mosby.

Public Health Theory

Public health theory is concerned with the health of human populations. Public health is a practice discipline that applies knowledge from the physical, biological, and social sciences to promote health and to prevent disease, injury, disability, and premature death. Epidemiology is the study of health in human populations and is explored in more detail in Chapter 7. Population, prevention, risk, and social justice are among the concepts from public health theory that are important to community health nursing. The first three concepts are discussed here, and justice is discussed later in this chapter.

Populations and Risk

Population has two meanings: people residing in an area, and a group or set of persons under statistical study. The word group is used here to mean a set or collection of persons, not a system of individuals who engage in face-to-face interactions, which is the definition of group used in the discussion of systems theory. The fact that there are many definitions for population and group leads to lack of clarity and fosters debate and dialogue.

Both definitions of population are used in public health and community health nursing. The initial goal of public health was to prevent or control communicable diseases that were the major causes of death within human populations (i.e., the people living in specific geographic or political areas). Today, for example, a director of nursing in a city health department is concerned with the health of the population within the city limits. When used in this way, population means all the people in the area or community. The noun public is often used as a synonym for this definition of population.

Because not everyone has the same health status, the second definition of population—a set of persons under statistical study—is especially important in public health practice. Using this definition, a population is a set of persons having a common personal or environmental characteristic. The common characteristic might be anything thought to relate to health, such as age, race, gender, social class, medical diagnosis, level of disability, exposure to a toxin, or participation in a health-seeking behavior such as smoking cessation. It is the researcher or health care practitioner who identifies the characteristic and set of persons that make up this population. In epidemiology, numerous sets of persons are studied clinically and statistically to identify the causes, methods of treatment, and means of prevention of diseases, accidents, disabilities, and premature deaths. In community/public health nursing, epidemiological information is used to identify populations at higher risk for specific preventable health conditions. Risk is a statistical concept based on probability. Community/public health nursing is concerned with human risk of disease, disability, and premature death. Therefore, community/public health nurses work with persons within the population to reduce their risk for developing such a health condition.

Aggregate is a synonym for the second definition of population. Aggregates are people who do not have the relatedness necessary to constitute an interpersonal group (system) but who have one or more characteristics in common, such as pregnant teenagers (Schultz, 1987). Williams (1977) focused attention on the aggregate as an additional type of client with whom community/public health nurses apply the problem-solving process. For example, aggregates can be identified by virtue of setting (those enrolled in a well-baby clinic), demographic characteristic (women), or health status (smokers or those with hypertension) (APHA, 1980, 1996). It is the community/public health nurse who identifies the aggregate by naming one or more common characteristics.

The terminology for statistical groups and aggregates is confusing. Although there are subtle differences, the terms at-risk population, specified population, and population group are used to mean aggregate. The APHA (1980, 1996) uses the term at-risk population in place of the term aggregate. In its description of community health nursing, the ANA (1980) uses the term specified population. Others use population group to mean a population that shares similar characteristics but has limited face-to-face interaction (Porter, 1987). It is important to remember that regardless of which of these terms is used, such a population is not a system. The individuals within these populations are not classified because of interaction or common goals. It is the community/public health nurse who conceptually classifies, collects, or aggregates the individuals into such a population. The individuals within such a population often might not even know one another. The nurse has identified the population to focus intervention efforts toward health promotion and prevention.

Prevention

Prevention is a complex concept that also evolved from an attempt to control diseases among the public. Epidemiology is the science that helps describe the natural history of specific diseases, their causes, and their treatments. The natural history of a disease includes a presymptomatic period, a symptomatic period, and a resolution (death, disability, complications, or recovery) (Friedman, 2003). The broad concept of prevention has three levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary. The goal of primary prevention is the promotion of health and the prevention of the occurrence of diseases. Activities of primary prevention include environmental protection (such as maintaining asepsis and providing clean water) and personal protection (such as providing immunizations and establishing smoke-free areas). The goal of secondary prevention is the detection (screening) and treatment of a disease as early as possible during its natural history. For example, Papanicolaou (Pap) smear testing allows cervical cancer to be detected earlier in the disease process so that cure is more likely. Tertiary prevention is geared toward preventing disability, complications, and death from diseases. Tertiary prevention includes rehabilitation.

All levels of prevention can be accomplished through work with individuals, families, and groups. Prevention can also be accomplished by targeting changes in the behaviors of specified populations, changes in social functioning of communities (law, social mores), and changes in the physical environment (waste disposal). The well-being and health of the entire population within the community is the ultimate goal of public health.

Goals for community/public health nursing

Care is always in the here and now, responsive to the needs of specific persons, in a specific place, at a specific time. It is always personal and intimate. Even when community/public health nurses work with other professionals and community groups, they express care through recognition of the uniqueness of each of the others.

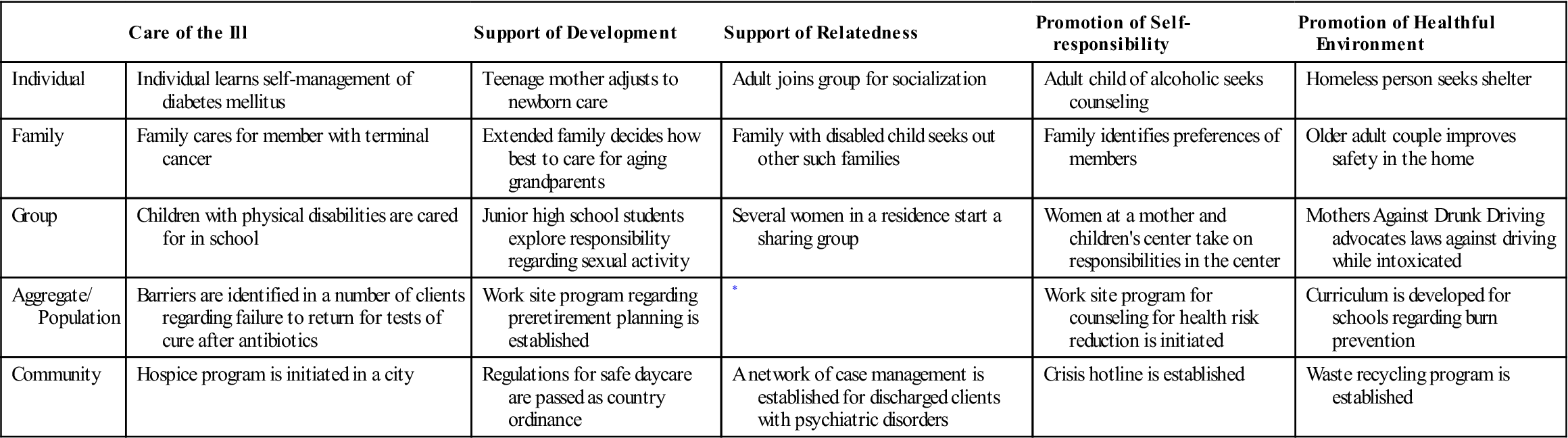

There are several major goals for community health nursing (Box 1-6). Table 1-2 identifies examples of health outcomes for each of the goals for each category of client. All nurses address these goals, but most do so with individuals, hospitalized individuals and their families or friends, and small groups. In addition to formulating these goals with individuals, community/public health nurses do the same with families, groups, aggregates, populations, and organizations/systems within the community.

Table 1-2

Examples of Health Outcomes Related to Goals of Community/Public Health Nursing

| Care of the Ill | Support of Development | Support of Relatedness | Promotion of Self-responsibility | Promotion of Healthful Environment | |

| Individual | Individual learns self-management of diabetes mellitus | Teenage mother adjusts to newborn care | Adult joins group for socialization | Adult child of alcoholic seeks counseling | Homeless person seeks shelter |

| Family | Family cares for member with terminal cancer | Extended family decides how best to care for aging grandparents | Family with disabled child seeks out other such families | Family identifies preferences of members | Older adult couple improves safety in the home |

| Group | Children with physical disabilities are cared for in school | Junior high school students explore responsibility regarding sexual activity | Several women in a residence start a sharing group | Women at a mother and children’s center take on responsibilities in the center | Mothers Against Drunk Driving advocates laws against driving while intoxicated |

| Aggregate/ Population | Barriers are identified in a number of clients regarding failure to return for tests of cure after antibiotics | Work site program regarding preretirement planning is established | * | Work site program for counseling for health risk reduction is initiated | Curriculum is developed for schools regarding burn prevention |

| Community | Hospice program is initiated in a city | Regulations for safe daycare are passed as country ordinance | A network of case management is established for discharged clients with psychiatric disorders | Crisis hotline is established | Waste recycling program is established |

*By definition, aggregates are individuals or families with common characteristics who are identified as such by the community health nurse or other professional. If such clients become known to one another and develop a sense of belonging or support, the aggregate would become a group or community.

Nursing ethics and social justice

The goals of community health nursing reflect the values and beliefs of both nursing and public health. Each profession has an ideology, or set of values, concepts, ideas, and beliefs, that defines its responsibilities and actions (Hamilton & Keyser, 1992). Ideologies are linked closely with ethics—the study of, and thinking about, what one ought to do (i.e., right conduct).

Public health and nursing are based on the same ethical principles: respecting autonomy, doing good, avoiding harm, and treating people fairly (Fry, 1983; Wallace, 2008) (Table 1-3). These principles are sometimes in conflict. Issues related to application of these principles are discussed in case examples in Ethics in Practice boxes (see Chapters 8 9 21 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, and 28).

Table 1-3

Basic Ethical Principles in Health Professions

| Principle | Definition | Example |

| Altruism | Concern for the welfare of others | Being present |

| Beneficence | Doing good | Providing immunizations |

| Nonmaleficence | Avoiding harm | Not abandoning client |

| Respect for autonomy | Honoring self-determination (i.e., right to make one’s own decisions; respecting privacy) | Allowing client to refuse treatment, informed consent; maintaining confidentiality |

| Veracity | Truth-telling | Communicating authentically and not lying |

| Fidelity | Keeping promises | Arriving on time for home visit |

| Justice | Treating people fairly | Providing nursing services to all, regardless of ability to pay |

Data from American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (1986). Essentials of college and university education for professional nursing, Washington, DC: The Association; and Beauchamp, T., & Childress, J. (2008). Principles of biomedical ethics (6th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Ethical Priorities

Historically, the ANA Code for Nurses (ANA, 1985, p. 2) stated that the most important ethical principle of nursing practice is “respect for the inherent dignity and worth … of human existence and the individuality of all persons” (Box 1-7). However, because public health is concerned with the well-being of the entire population, the foremost ethical principle of public health practice is doing good for the greatest number of persons with the least amount of harm. Consequently, in community health nursing, there is a tension between an individual-focused ethic and a society-focused ethic (Fry, 1983; Hamilton & Keyser, 1992). Community/public health nurses consider both ethical perspectives.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree