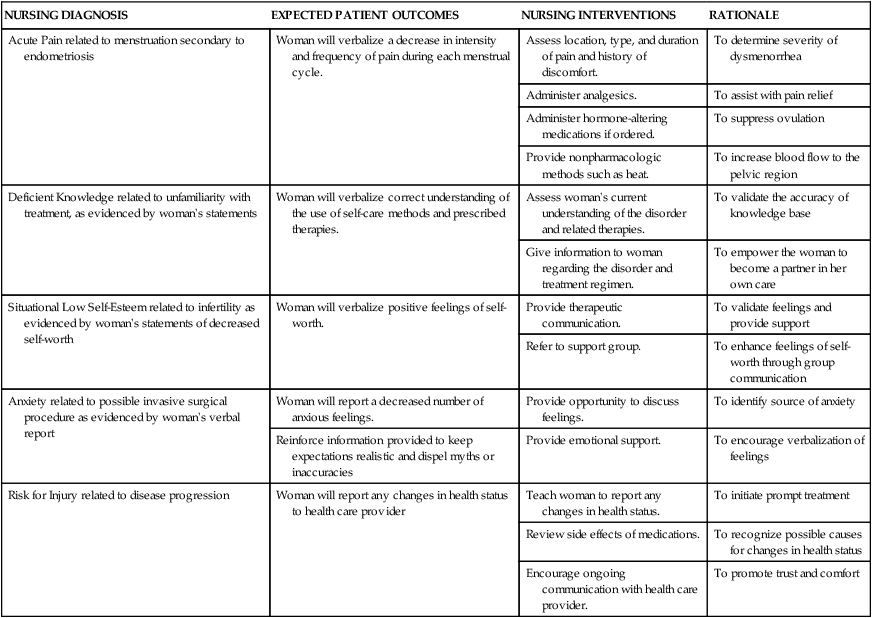

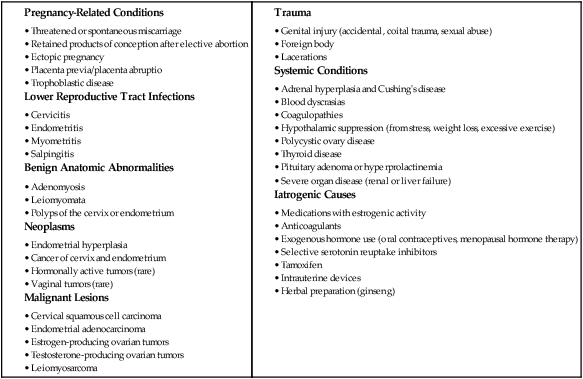

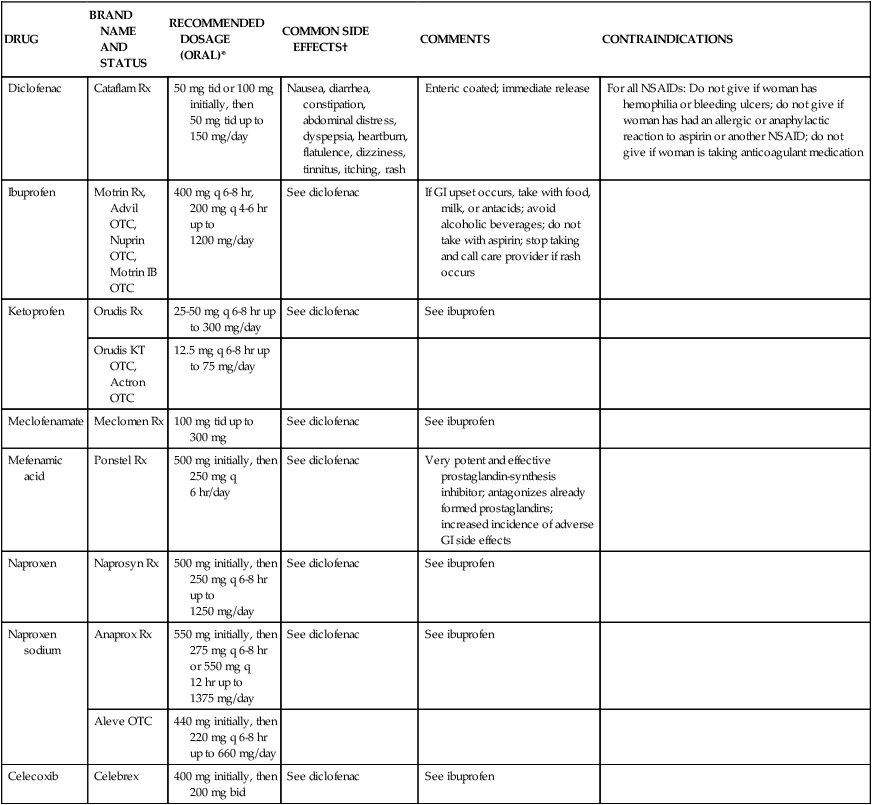

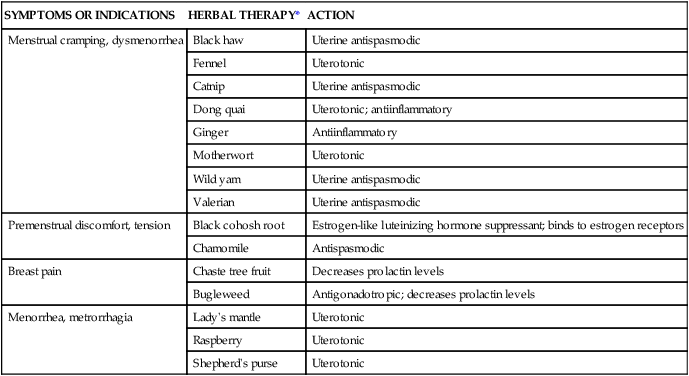

Chapter 4 On completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to: • Differentiate among the signs and symptoms of common menstrual disorders. • Develop a nursing care plan for the woman with primary dysmenorrhea. • Outline patient teaching about premenstrual syndrome. • Relate the pathophysiology of endometriosis to associated symptoms. • Evaluate the use of alternative therapies for menstrual disorders. • Describe prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections in women. • Summarize the care of women with selected viral infections (i.e., human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus). • Differentiate signs, symptoms, and management of selected vaginal infections. • Review principles of infection control for human immunodeficiency virus and bloodborne pathogens. • Discuss the pathophysiology and emotional effects of selected benign breast conditions and malignant neoplasms of the breasts found in women. Amenorrhea, the absence of menstrual flow, is a clinical sign of a variety of disorders. Generally the following circumstances should be evaluated: (1) the absence of both menarche and secondary sexual characteristics by age 13 years; (2) the absence of menses by age 16.5 years, regardless of normal growth and development (primary amenorrhea); or (3) a 6-month or more cessation of menses after a period of menstruation (secondary amenorrhea) (Lobo, 2012d). A moderately obese girl (20% to 30% above ideal weight) may have early-onset menstruation, whereas delay of onset is known to be related to malnutrition (starvation such as that with anorexia). Girls who exercise strenuously before menarche can have delayed onset of menstruation until about age 18 (Lobo, 2012d). Hypogonadotropic amenorrhea often results from hypothalamic suppression as a result of stress (in the home, school, or workplace) or a sudden and severe weight loss, eating disorders, strenuous exercise, or mental illness (Wambach and Alexander, 2012). Research on the interaction between nervous system or neurotransmitter functions and hormone regulation throughout the body has demonstrated a biologic basis for the relation of stress to physiologic processes. Women who are more than 20% underweight for height or who have had rapid weight loss and women with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa may report amenorrhea. Amenorrhea is one of the classic signs of anorexia nervosa; and the interrelation of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and premature osteoporosis has been described as the female athlete triad (George, Leonard, and Hutchinson, 2011) (www.femaleathletetriad.org). A loss of calcium from the bone, comparable to that seen in postmenopausal women, may occur with this type of amenorrhea. • Sports in which performance is subjectively scored (e.g., dance, gymnastics) • Endurance sports favoring participants with low body weight (e.g., distance running, cycling) • Sports in which body contour–revealing clothing is worn (e.g., swimming, diving, volleyball) • Sports with weight categories for participation (e.g., rowing, martial arts) • Sports in which prepubertal body shape favors success (e.g., gymnastics, figure skating). Assessment of amenorrhea begins with a thorough history and physical examination. Specific components of the assessment process depend on a patient’s age—adolescent, young adult, or perimenopausal—and whether she has menstruated previously. An important initial step, often overlooked, is to be sure that the woman is not pregnant. Once pregnancy has been ruled out by a β-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) pregnancy test, diagnostic tests may include FSH level, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin levels, radiographic or computed tomography (CT) scan of the sella turcica, and a progestational challenge (Lobo, 2012d). Although research on effectiveness is inconclusive, a daily calcium intake of 1200 to 1500 mg plus 400 to 800 International Units of vitamin D and 60 to 90 mg of potassium are recommended for women experiencing amenorrhea associated with the female athlete triad. Oral contraceptives have a positive effect on bone density in amenorrheic women but are usually not used in young women with amenorrhea associated with female athlete triad unless the woman is not willing to comply with dietary and exercise recommendations or she continues to be amenorrheic even with compliance (Joy, 2012). Dysmenorrhea, pain during or shortly before menstruation, is one of the most common gynecologic problems in women of all ages. Many adolescents have dysmenorrhea in the first 3 years after menarche. Young adult women ages 17 to 24 years are most likely to report painful menses. Approximately 75% of women report some level of discomfort associated with menses, and approximately 15% report severe dysmenorrhea (Lentz, 2012); however, the amount of disruption in women’s lives is difficult to determine. Researchers have estimated that as many as 10% of women with dysmenorrhea have severe enough pain to interfere with their functioning for 1 to 3 days a month. Menstrual problems, including dysmenorrhea, are relatively more common in women who smoke and are obese. Severe dysmenorrhea is also associated with early menarche, nulliparity, and stress (Lentz, 2012). Traditionally dysmenorrhea is differentiated as primary or secondary. Symptoms usually begin with menstruation, although some women have discomfort several hours before onset of flow. The range and severity of symptoms are different from woman to woman and from cycle to cycle in the same woman. Symptoms of dysmenorrhea may last several hours or several days. Primary dysmenorrhea is a condition associated with ovulatory cycles. Research has shown that primary dysmenorrhea has a biochemical basis and arises from the release of prostaglandins with menses. During the luteal phase and subsequent menstrual flow, prostaglandin F2-alpha (PGF2α) is secreted. Excessive release of PGF2α increases the amplitude and frequency of uterine contractions and causes vasospasm of the uterine arterioles, resulting in ischemia and cyclic lower abdominal cramps. Systemic responses to PGF2α include backache, weakness, sweats, gastrointestinal symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), and central nervous system symptoms (dizziness, syncope, headache, and poor concentration). Pain usually begins at the onset of menstruation and lasts 8 to 48 hours (Lentz, 2012). Often you can offer more than one alternative for alleviating menstrual discomfort and dysmenorrhea, which gives women options to try to decide which works best for them (see Critical Thinking Case Study). Heat (heating pad or hot bath) minimizes cramping by increasing vasodilation and muscle relaxation and minimizing uterine ischemia. Massaging the lower back can reduce pain by relaxing paravertebral muscles and increasing the pelvic blood supply. Soft, rhythmic rubbing of the abdomen (effleurage) is useful because it provides a distraction and an alternative focal point. Biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), progressive relaxation, Hatha yoga, acupuncture, and meditation are also used to decrease menstrual discomfort, although evidence is insufficient to determine their effectiveness (Lentz, 2012) (Fig. 4-1). In addition to maintaining good nutrition at all times, specific dietary changes are helpful in decreasing some of the systemic symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea. Decreased salt and refined sugar intake 7 to 10 days before expected menses may reduce fluid retention. Natural diuretics such as asparagus, cranberry juice, peaches, parsley, or watermelon may help reduce edema and related discomforts. A low-fat vegetarian diet may also help minimize dysmenorrheal symptoms (Lentz, 2012). Medications used to treat primary dysmenorrhea include prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, primarily nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Lentz, 2012) (Table 4-1). NSAIDs are most effective if started several days before menses or at least by the onset of bleeding. All NSAIDs have potential gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and indigestion. Warn all women taking them to report dark-colored stool because this may be an indication of gastrointestinal bleeding. TABLE 4-1 NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY AGENTS USED TO TREAT DYSMENORRHEA GI, Gastrointestinal; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug; OTC, over the counter. Data from Facts and Comparisons: Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, 2012, www.factsandcomparisons.com; Lentz GM: Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: etiology, diagnosis, and management. In Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, et al, editors: Comprehensive gynecology, ed 6, Philadelphia, 2012, Mosby; US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration: Medication guide for nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), 2008, www.fda.gov/CDER/drug/infopage/COX2/NSAIDmedguide.htm. OCPs are a reasonable choice for women who want to use a contraceptive agent. The benefits of their use are attributed to decreased prostaglandin synthesis associated with an atrophic decidualized endometrium (Lentz, 2012). OCPs are effective in relieving symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea for approximately 90% of women. No single OCP has been shown to be superior to another for the relief of primary dysmenorrheal, including low-dose and extended-cycle OCPS (Lentz, 2012). OCPs are a particularly good choice for therapy because they combine contraception with a positive effect on dysmenorrhea, menstrual flow, and menstrual irregularities. Adolescents may benefit from use of the long-acting injectable contraceptive (depot medroxyprogesterone), but more research is needed. Since OCPs have side effects, women may not wish to use them for dysmenorrhea. They may be contraindicated for some women. (See Chapter 5 for a complete discussion of OCPs.) Alternative and complementary therapies are increasingly popular and used in developed countries. Therapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, biofeedback, desensitization, hypnosis, massage, reiki, relaxation exercises, and therapeutic touch have been used to treat pelvic pain. Herbal preparations have long been used for managing menstrual problems, including dysmenorrhea (Table 4-2). Herbal medicines may be valuable in treating dysmenorrhea. However, it is essential that women understand that these therapies are not without potential toxicity and may cause drug interactions. TABLE 4-2 HERBAL MEDICINALS TAKEN ORALLY FOR MENSTRUAL DISORDERS *Many women’s herbs do not have rigorous scientific studies backing their use; most uses and properties of herbs have not been validated by the US Food and Drug Administration,. Data from Annie’s Remedy: Herbal remedies for dysmenorrhea, 2012, www.anniesremedy.com; National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Herbs at a glance, 2010, www.nccam.nih.gov. Approximately 30% to 80% of women experience mood or somatic symptoms (or both) that occur with their menstrual cycles (Lentz, 2012). Establishing a universal definition of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is difficult, given that so many symptoms have been associated with the condition and at least two different syndromes have been recognized: PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). PMDD is a more severe variant of PMS in which 3% to 8% of women have marked irritability, dysphoria, mood lability, anxiety, fatigue, appetite changes, and a sense of feeling overwhelmed (Lentz, 2012). The most common symptoms are those associated with mood disturbances. A diagnosis of PMS is made when the following criteria are met (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2000): • Symptoms consistent with PMS occur in the luteal phase and resolve within a few days of menses onset. • Symptom-free period occurs in the follicular phase. • Symptoms have a negative effect on some aspect of a woman’s life. • Other diagnoses that better explain the symptoms have been excluded. For a diagnosis of PMDD, the following criteria must be met (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000): • Five or more affective and physical symptoms are present in the week before menses and absent in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. • At least one of the symptoms is irritability, depressed mood, anxiety, or emotional lability. • Symptoms interfere markedly with work or interpersonal relationships. • Symptoms are not caused by an exacerbation of another condition or disorder. These criteria must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings for at least two menstrual cycles. The causes of PMS and PMDD continue to be investigated, but there is general agreement that they are distinct psychiatric and medical syndromes rather than an exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric disorder. They do not occur if there is no ovarian function. A number of biologic and neuroendocrine etiologies have been suggested; however, none have been conclusively substantiated as the causative factor. It is likely that biologic, psychosocial, and sociocultural factors contribute to PMS and PMDD (Lentz, 2012). Education is an important component of the management of PMS. Nurses can advise women that self-help modalities often result in significant symptom improvement. Women have found a number of complementary and alternative therapies to be useful in managing the symptoms of PMS. Diet and exercise changes can provide symptom relief for some women. Nurses can suggest that women not smoke and limit their consumption of refined sugar, salt, red meat, alcohol, and caffeinated beverages. Women can be encouraged to include whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oils in their diet. Three small to moderate-size meals and three small snacks a day that are rich in complex carbohydrates and fiber have been reported to relieve symptoms (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] 2011; Lentz, 2012). Use of natural diuretics (see section on dysmenorrhea management on pp. 76-78) may also help reduce fluid retention. Nutritional supplements may assist in symptom relief. Calcium (1200 mg daily) and vitamin B6 have been shown to be moderately effective in relieving symptoms, to have few side effects, and to be safe. Daily supplements of evening primrose oil are reportedly useful in relieving breast symptoms with minimal side effects, but research reports are conflicting (Biggs and Demuth, 2011; Lentz, 2012). Other herbal therapies have long been used to treat PMS; however, research on effectiveness is lacking, or studies are flawed (Dante and Facchinetti, 2011). Regular exercise (aerobic exercise three or four times a week), especially in the luteal phase, is widely recommended for relief of PMS symptoms (Lentz, 2012). A monthly program that varies in intensity and type of exercise according to PMS symptoms is best. Women who exercise regularly seem to have less premenstrual anxiety than do nonathletic women. Researchers believe aerobic exercise increases beta-endorphin levels to offset symptoms of depression and elevate mood. Nurses can explain the relation between cyclic estrogen fluctuation and changes in serotonin levels, that serotonin is one of the brain chemicals that assist in coping with normal life stresses, and the ways in which the different management strategies recommended help maintain serotonin levels. Support groups or individual or couples counseling may be helpful. Stress-reduction techniques also may help with symptom management (Lentz, 2012). If these strategies do not provide significant symptom relief in 1 to 2 months, medication is often added. Many medications have been used in treatment of PMS, but no single medication alleviates all PMS symptoms. Medications often used in the treatment of PMS include diuretics, prostaglandin inhibitors (NSAIDs), progesterone, and OCPs. These have been used mainly for the physical symptoms. Studies of progesterone have not shown that it is an effective treatment (Ford, Lethaby, Roberts, et al., 2012). Serotonergic-activating agents, including the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine (Prozac or Sarafem), sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), escitalopram (Lexapro), and paroxetine (Paxil CR) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as agents for PMS and are first-line pharmacologic therapy. Use of these medications during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle results in a decrease in emotional premenstrual symptoms, especially depression (Biggs and Demuth, 2011; Lentz, 2012). Common side effects are headaches, sleep disturbances, dizziness, weight gain, dry mouth, and decreased libido. Endometriosis is characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial tissue outside of the uterus. The tissue may be implanted on the ovaries; anterior and posterior cul-de-sac; broad, uterosacral, and round ligaments; rectovaginal septum; sigmoid colon; appendix; pelvic peritoneum; cervix; and inguinal area (Fig. 4-2). Endometrial lesions have been found in the vagina and surgical scars and on the vulva, perineum, and bladder. They have also been found on sites far from the pelvic area such as the thoracic cavity, gallbladder, and heart. A cystic lesion of endometriosis found in the ovary is sometimes described as a chocolate cyst because of the dark coloring of the contents of the cyst caused by the presence of old blood. The overall incidence of endometriosis is 5% to 15% in reproductive-age women, 30% to 45% in infertile women, and 33% in women with chronic pelvic pain (Lobo, 2012b). Although the condition usually develops in the third or fourth decade of life, endometriosis has been found in adolescents with disabling pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding. Endometriosis may worsen with repeated cycles, or it may remain asymptomatic and undiagnosed, eventually disappearing after menopause. However, it has been reported to occur in about 5% of postmenopausal women receiving menopausal hormone therapy. There appears to be a familial tendency to develop endometriosis; the condition is 7 times more prevalent in women who have a first-degree relative with endometriosis as compared to the general population (Lobo, 2012b). Several theories concerning the cause of endometriosis have been suggested. However, the etiology and pathology of this condition continue to be poorly understood. One of the most widely accepted theories is transplantation or retrograde menstruation. According to this theory, endometrial tissue is refluxed through the uterine tubes during menstruation into the peritoneal cavity, where it implants on the ovaries and other organs. Retrograde menstruation has been documented in a number of surgical studies and is estimated to occur in 90% of menstruating women. For most women endometrial tissue outside the uterus is destroyed before it can implant or seed in the peritoneal cavity or elsewhere. Other theories include genetic disposition, immunologic changes, and hormonal influences (Lobo, 2012b). Symptoms from nonexistent to incapacitating vary among women. Severity of symptoms can change over time and may not reflect the extent of the disease. The major symptoms of endometriosis are pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse). Women may also have chronic noncyclic pelvic pain, pelvic heaviness, or pain radiating into the thighs. Many women report bowel symptoms such as diarrhea, pain with defecation, and constipation caused by avoiding defecation because of the pain. Less common symptoms include abnormal bleeding (hypermenorrhea, menorrhagia, or premenstrual staining) and pain during exercise as a result of adhesions (Lobo, 2012b). Suppression of endogenous estrogen production and subsequent endometrial lesion growth is the cornerstone of management of the disease. Two main classes of medications are used to suppress endogenous estrogen levels: gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists and androgen derivatives. GnRH agonist therapy (leuprolide [Lupron], nafarelin acetate [Synarel], goserelin acetate [Zoladex]) acts by suppressing pituitary gonadotropin secretion. FSH and LH stimulation of the ovary declines markedly, and ovarian function decreases significantly. A medically induced menopause develops, resulting in anovulation and amenorrhea. Shrinkage of already established endometrial tissue, significant pain relief, and interruption in further lesion development follow. The hypoestrogenism results in hot flashes in almost all women. Trabecular bone loss is common, although most loss is reversible within 12 to 24 months after the medication is stopped (Lobo, 2012b). Leuprolide (3.75 mg intramuscular injection given once a month), nafarelin (200 mg administered twice daily by nasal spray), and goserelin 3.6 mg every 28 days by subcutaneous implant are effective and well tolerated. These medications reduce endometrial lesions and pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and have posttreatment pregnancy rates similar to that of danazol (Danocrine) therapy (Lobo, 2012b). Common side effects of these drugs are those of natural menopause—hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Occasionally women report headaches and muscle aches. Treatment is usually limited to 6 months to minimize bone loss. Although unlikely, it is possible for a woman to become pregnant while taking a GnRH agonist. Because the potential teratogenicity of this drug is unclear, women should use a barrier contraceptive during treatment. Danazol, a mildly androgenic synthetic steroid, suppresses FSH and LH secretion, thus producing anovulation and hypogonadotropism. This results in decreased secretion of estrogen and progesterone and regression of endometrial tissue. Danazol can produce side effects severe enough to cause a woman to discontinue the drug, including masculinizing traits (weight gain, edema, decreased breast size, oily skin, hirsutism, and deepening of the voice), all of which often disappear when treatment is discontinued. Other side effects are amenorrhea, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, insomnia, and decreased libido. Migraine headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and depression are also reported. Danazol treatment has been reported to adversely affect lipids, with a decrease in high-density lipoprotein levels and an increase in low-density lipoprotein levels. Danazol should never be prescribed when pregnancy is suspected, and barrier contraception should be used with it because ovulation may not be suppressed. Danazol can produce pseudohermaphroditism in female fetuses. The medication is contraindicated in women with liver disease and should be used with caution in women with cardiac and renal disease. Danazol is less frequently used to treat endometriosis than other medical therapies (Lobo, 2012b). Women who have early symptomatic disease and who can postpone pregnancy may be treated with continuous OCPs that have a low estrogen-to-progestin ratio to shrink endometrial tissue. Any low-dose OCPs can be used if taken for 15 weeks, followed by 1 week of withdrawal. This therapy is associated with minimal side effects and can be taken for extended periods (Lobo, 2012b). Limited data exist on the effectiveness of progestogen-only medications for treating pain related to endometriosis (Brown, Kives, and Akhtar, 2012). Continuous combined hormone therapy (OCPs, estrogen/progestin patch, estrogen/progestin vaginal ring) for menstrual suppression and administration of NSAIDs are the usual treatment for adolescents under the age of 16 who have endometriosis. GnRH agonist therapy for severe symptoms may have possible adverse effects on bone mineralization in adolescents, and bone mineral density should be carefully monitored (Laufer, 2008). Surgical intervention is often needed for severe, acute, or incapacitating symptoms. Decisions regarding the extent and type of surgery are influenced by a woman’s age, desire for children, and location of the disease. For women who do not want to preserve their ability to have children, the only definite cure is total abdominal hysterectomy with BSO (TAH with BSO). In women who want children and in whom the disease does not prevent bearing children, reproductive capacity should be retained through careful removal by laparoscopic surgery or laser therapy (coagulation, vaporization, or resection) of all endometrial tissue possible with retention of ovarian function (Lobo, 2012b). Regardless of the type of treatment (short of TAH with BSO), endometriosis recurs in approximately 40% of women. Thus for many women endometriosis is a chronic disease with conditions such as chronic pain or infertility. Counseling and education are critical components of nursing care for women with endometriosis. Women need an honest discussion of treatment options, with review of the potential risks and benefits of each option. Because pelvic pain is a subjective, personal experience that can be frightening, support is important. Sexual dysfunction resulting from dyspareunia is common and may necessitate referral for counseling. Support groups for women with endometriosis may be found in some locations. Resolve (www.resolve.org), an organization for infertile couples, or the Endometriosis Association (www.ivf.com/endohtml.html) may also be helpful. The nursing care discussed in the previous section on dysmenorrhea is appropriate for managing chronic pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea experienced by women with endometriosis (see Nursing Care Plan). Uterine leiomyomas (fibroids or myomas) are a common cause of menorrhagia. Fibroids are benign tumors of the smooth muscle of the uterus with an unknown cause. Fibroids occur in approximately one fourth of women of reproductive age; their incidence is higher in African-American women than in Caucasian, Asian, or in Hispanic women (Katz, 2012). Other uterine growths ranging from endometrial polyps to adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer are common causes of heavy menstrual bleeding and intermenstrual bleeding. If there is no known cause for the bleeding and anatomic causes have been rules out, therapy is aimed at reducing the amount of heavy bleeding. Current options for treatment include OCPs and NSAIDs (non–Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved for this use) and FDA-approved therapies: the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD and antifibrinolytic agents (e.g., tranexamic acid) (Lobo, 2012a, Wilton, 2012). If bleeding is related to the presence of fibroids, the degree of disability and discomfort associated with the fibroids and the woman’s plans for childbearing influence treatment decisions. Treatment options include medical and surgical management. Most fibroids can be monitored by frequent examinations to judge growth, if any, and correction of anemia if present. Warn women with metrorrhagia to avoid using aspirin because of its tendency to increase bleeding. Medical treatment is directed toward temporarily reducing symptoms, shrinking the myoma, and reducing its blood supply (Katz, 2012). This reduction is often accomplished with the use of a GnRH agonist. However, usually after cessation of this treatment, the myomas return to their pretreatment size (Katz, 2012). If the woman wishes to retain childbearing potential, a myomectomy may be performed. Myomectomy, or removal of the tumors only by laparoscopic or hysteroscopic resection or laser surgery, is particularly difficult if multiple myomas must be removed. One in four women will have a hysterectomy performed within 20 years of having a myomectomy. If the woman does not want to preserve her childbearing function or if she has severe symptoms (severe anemia, severe pain, considerable disruption of lifestyle), uterine artery embolization (UAE) (procedure that blocks blood supply to fibroid), or hysterectomy (removal of uterus) may be performed. After UAE 20% to 30% of women will undergo a hysterectomy within 5 years (Katz, 2012). Important nursing roles include reassurance, counseling, education, and support. Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is any form of uterine bleeding that is irregular in amount, duration, or timing and is not related to regular menstrual bleeding. Box 4-1 lists possible causes of AUB. Although often used interchangeably, the terms AUB and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) are not synonymous. AUB can have organic causes such as systemic diseases, reproductive tract disease, or DUB that is usually hormonally related. DUB can be anovulatory or ovulatory but is most commonly caused by anovulation. When no surge of LH occurs or if insufficient progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum to support the endometrium, it will begin to involute and shed. This process most often occurs at the extremes of a woman’s reproductive years, when the menstrual cycle is just becoming established at menarche or when it draws to a close at menopause. DUB also occurs with any condition that gives rise to chronic anovulation associated with continuous estrogen production. Such conditions include obesity, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and any of the endocrine conditions discussed in the sections on amenorrhea oligomenorrhea. A diagnosis of DUB is made only after ruling out all other causes of abnormal menstrual bleeding (Lobo, 2012a). The most effective medical treatment of acute bleeding episodes of DUB is administration of oral or intravenous estrogen. D&C may be done if the bleeding has not stopped in 12 to 24 hours. An oral conjugated estrogen and progestin regimen is usually given for at least 3 months after the acute phase has passed. Such long-term treatment will help prevent recurrence of the pattern of DUB and hemorrhage. If the woman wants contraception, she should continue to take OCPs. If she has no need for contraception, the treatment may be stopped to assess the woman’s bleeding pattern. If her menses does not resume, a progestin regimen (e.g., medroxyprogesterone, 10 mg each day for 10 days before the expected date of her menstrual period) may be prescribed after ruling out pregnancy. This is done to prevent persistent anovulation with chronic unopposed endogenous estrogen hyperstimulation of the endometrium, which can result in eventual atypical tissue changes (Lobo, 2012a). Nursing assessments for women who have a menstrual disorder include: • Taking a thorough menstrual, obstetric, sexual, and contraceptive history. • Exploring the woman’s perceptions of her condition, cultural or ethnic influences, lifestyle, and patterns of coping. • Evaluating the amount of pain or bleeding experienced and its effect on daily activities. • Noting any home remedies and prescriptions to relieve discomfort. A symptom diary, in which the woman records emotions, behaviors, physical symptoms, diet, and exercise and rest patterns, is a useful diagnostic tool. Possible nursing diagnoses include: • Risk for Ineffective Individual Coping related to: • Deficient Knowledge related to: • Risk for Disturbed Body Image related to: • Risk for Situational Low Self-Esteem related to: • Acute or Chronic Pain related to: Expected outcomes for the woman are that she will do the following: • Verbalize her understanding of reproductive anatomy, cause of her disorder, medication regimen, and diary use. • Verbalize her understanding and accept her emotional and physical responses to her menstrual cycle. • Develop personal goals that benefit her emotionally and physically. • Choose appropriate therapeutic measures for her menstrual problems. • Adapt successfully to the condition if cure is not possible. In addition to the medical, surgical, and nursing interventions discussed with each problem, additional nursing interventions may include: • Accepting the woman’s symptoms as valid. • Correlating data from the daily diary of emotional status, subjective feelings, and physical state with physiologic changes. • Encouraging the woman to express her feelings about her symptoms. • Providing information about therapeutic options (pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic) so the woman (couple) makes (make) choices considered best for her (them). Care has been effective when the woman reports improvement in the quality of her life, skill in self-management, and a positive self-concept and body image. Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are infections or infectious disease syndromes transmitted primarily by sexual contact. The term sexually transmitted infection includes more than 25 infectious organisms that are transmitted through sexual activity and the dozens of clinical syndromes that they cause (Box 4-2). STIs are among the most common health problems in the United States today, with an estimated 19 million people in the United States being infected with STIs every year (CDC, 2010a). The following discussion focuses on the most common STIs in women. Chapter 25 discusses neonatal effects.

Reproductive System Concerns

Menstrual Disorders

Amenorrhea

Hypogonadotropic Amenorrhea

Management.

Dysmenorrhea

Primary Dysmenorrhea

Management.

DRUG

BRAND NAME AND STATUS

RECOMMENDED DOSAGE (ORAL)*

COMMON SIDE EFFECTS†

COMMENTS

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Diclofenac

Cataflam Rx

50 mg tid or 100 mg initially, then 50 mg tid up to 150 mg/day

Nausea, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal distress, dyspepsia, heartburn, flatulence, dizziness, tinnitus, itching, rash

Enteric coated; immediate release

For all NSAIDs: Do not give if woman has hemophilia or bleeding ulcers; do not give if woman has had an allergic or anaphylactic reaction to aspirin or another NSAID; do not give if woman is taking anticoagulant medication

Ibuprofen

Motrin Rx, Advil OTC, Nuprin OTC, Motrin IB OTC

400 mg q 6-8 hr, 200 mg q 4-6 hr up to 1200 mg/day

See diclofenac

If GI upset occurs, take with food, milk, or antacids; avoid alcoholic beverages; do not take with aspirin; stop taking and call care provider if rash occurs

Ketoprofen

Orudis Rx

25-50 mg q 6-8 hr up to 300 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Orudis KT OTC, Actron OTC

12.5 mg q 6-8 hr up to 75 mg/day

Meclofenamate

Meclomen Rx

100 mg tid up to 300 mg

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Mefenamic acid

Ponstel Rx

500 mg initially, then 250 mg q 6 hr/day

See diclofenac

Very potent and effective prostaglandin-synthesis inhibitor; antagonizes already formed prostaglandins; increased incidence of adverse GI side effects

Naproxen

Naprosyn Rx

500 mg initially, then 250 mg q 6-8 hr up to 1250 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Naproxen sodium

Anaprox Rx

550 mg initially, then 275 mg q 6-8 hr or 550 mg q 12 hr up to 1375 mg/day

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

Aleve OTC

440 mg initially, then 220 mg q 6-8 hr up to 660 mg/day

Celecoxib

Celebrex

400 mg initially, then 200 mg bid

See diclofenac

See ibuprofen

SYMPTOMS OR INDICATIONS

HERBAL THERAPY*

ACTION

Menstrual cramping, dysmenorrhea

Black haw

Uterine antispasmodic

Fennel

Uterotonic

Catnip

Uterine antispasmodic

Dong quai

Uterotonic; antiinflammatory

Ginger

Antiinflammatory

Motherwort

Uterotonic

Wild yam

Uterine antispasmodic

Valerian

Uterine antispasmodic

Premenstrual discomfort, tension

Black cohosh root

Estrogen-like luteinizing hormone suppressant; binds to estrogen receptors

Chamomile

Antispasmodic

Breast pain

Chaste tree fruit

Decreases prolactin levels

Bugleweed

Antigonadotropic; decreases prolactin levels

Menorrhea, metrorrhagia

Lady’s mantle

Uterotonic

Raspberry

Uterotonic

Shepherd’s purse

Uterotonic

Premenstrual Syndrome

Management

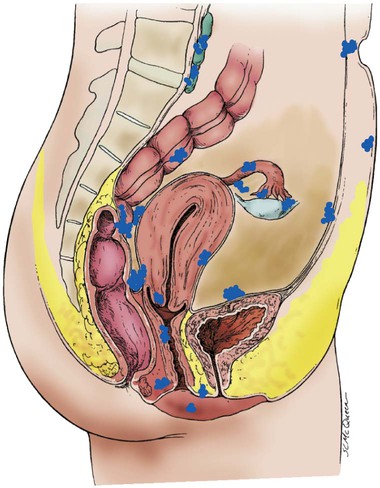

Endometriosis

Management

Alterations in Cyclic Bleeding

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Management.

Care Management

Infections

Sexually Transmitted Infections